About the project

The fading miscellany of languages

More and more often the topic of language diversity and its slow disappearance is being contemplated, discussed and researched on various levels and from different standpoints. Generally, though, the notion of language extinction is associated with far-off regions such as the islands of Oceania, Africa, the two continents of America, Siberia and Australia (which represent almost every continent). Europe is much less often considered in such deliberations even though it is known that there are languages which face extinction, such as Irish or languages groups such as the Sorbian languages, Saami languages, Rhaeto-Romance languages and so on.

The web portal Languages in Danger has focused on various aspects of linguistics and the documentation and revitalization of endangered languages: http://languagesindanger.eu. We recommend the following for those interested in the topic:

- Languages of the World - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/languages-of-the-world

- Exploring Linguistic Diversity - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/exploring-linguistic-diversity

- Language and Culture - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/language-and-culture

- Multilingualism and Language Contact - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/multilingualism-and-language-contact

- Language Endangerment - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/language-endangerment

- Endangered languages, Ethnicity, Identity and Politics - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/endangered-languages-ethnicity-identity-and-politics

- Language Documentation - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/language-documentation

- What can you do - http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/what-can-be-done

- the documentation of disappearing language varieties - done by recording the (last) speakers of a given variety, by searching and gathering archival materials, collecting and working with photographic, printed and handwritten materials as well as cataloguing and annotating them;

- the revitalization of the given language communities - done by preparing and launching project which strive to collect the remnants of a community's language heritage and remind them of it; by conducting educational programmes in pre-schools and early primary education via, the so called, immersion programmes; by normalising the usage of the language and popularizing (one of the) spoken language varieties.

It should be mentioned that at a certain stage of language death/extinction the second way may be impossible to achieve without the first one. As such, projects which strive to comprehensively gather and collect linguistic resources are of even greater value.

Heritage languages of Poland

The territory of the Republic of Poland has always been inhabited by communities speaking languages different than Polish. Hence, the meaning of the web-site name in Polish: inne-jezyki.amu.edu.pl (‘other languages’). Of course, their array changed; the languages themselves changed, and so did the communities who spoke them and who rendered these languages as means of intra-group communication; and, finally, throughout history, the territory of Rzeczpospolita has been changing like of no other political body in Europe.

The multinational character of the I Republic (up to 1795) and II Republic of Poland (1918-1939) and, particularly, of the Commonwealth of Both Nations (Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), stemmed from the vastness and diversity of the lands which constituted parts of the once largest country in Europe. This diversity of non-Polish languages complemented the richness of the dialects and varieties of the Polish language itself. At that time, when they were largely unexplored, they must have diverged from each other to a much greater extent than their contemporary dialectological distance and research suggest (scholars began to be interested in Polish dialects only at the beginning of the 19th century).

More on history of Polish dialectology and dialects of Polish: http://www.gwarypolskie.uw.edu.pl, the web-page which directly inspired our team to start the present project.

Let us take a look at the languages which encompassed this multinational federation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth:

- Polish,

- Belarusian (Old-Belarusian served as the chancery language in the Great Duchy of Lithuania, therefore it is known also as Chancery Slavic),

- Ukrainian (labeled Lesser-Russian or Ruthenian in the past),

- Lithuanian, or actually two dialect continua: Samogitian or Žemaitian (Western or Lowland Lithuanian) and Aukštaitian (Eastern or Highland Lithuanian).

The inhabitants of the Rzeczpospolita-Commonwealth were also speakers of:

- German, or actually a miscellany of German dialects, including Low German in Pomerania and East Prussia, mixed urban varieties (as e.g. Danziger Missingsch) or Silesian, colonial and other dialects (of Middle and sometimes Upper German origin) throughout the entire territory of Poland;

- worth mentioning is the Mennonites’ Plautdietsch, which has developed into a separate Low-Germanic ethno-confessiolect; originally the outcast Mennonites used to speak Dutch or Frisian dialects;

- Jewish languages – predominantly Germanic Yiddish spoken by the Ashkenazim, but also Romance Ladino (Judaeo-Spanish) by the Sepharadim who reportedly settled in Zamość and vicinities;

- Gdańsk/Danzig attracted speakers of Scots, while Elbląg/Elbing was home to the English(-language) Merchants’ Eastland Company;

The Balkan shepherds, who progressively colonized the Carpathian range spoke Vlakh, an Eastern Romance language related to Old Romanian. Numerous Vlakh loanwords fund their way to Podhale Highlanders’ dialect, as well as to the East Slavic Hutsul, Boiko and Lemko;

the latter is nowadays commonly regarded as a separate (Rusyn) language, while Hutsul and Boiko are classified as (sub)Carpathian dialects of Ukrainian.

The vassal county of Spiš/Zips/Szepesz/Spisz was a multilingual region with Slovak, Hungarian, German, Rusyn, Yiddish, Romani, Polish, and other.

Silesia became refuge to the Bohemian or Moravian Brethren outcast from Czech lands, who later founded numerous Czech enclaves in central Poland and Volhynia.

The south-western confines of the Polish linguistic area could witness Polish-Lusatian (nowadays referred to as Sorbian) language contacts.

Subjects of the Rzeczpospolita spoke Turkic languages too:

- Karaim (which split into two dialects: Trakai-Vilnius and Lutsk-Halych),

- Tatar (spoken by Kypchak descendants and settlers from the Golden Horde),

- Armeno-Kipchak (language of the Armenians, who moved from the Crimean Peninsula to south-eastern Rzeczpospolita),

- other Turkic varieties spoken by Greek, Ottoman and Persian merchants.

Armenian settlers could have used Western Armenian (an Indo-European language not related to Kipchak Turkic varieties).

The nomadic Gypsy tribes have spoken Indo-Arian Romani varieties.

The regions known today as Warmia, Masuria, Suvalkia and northern Podlachia were home to two extinct Baltic languages/peoples: (Old-)Prussian and Yatvingian; the former has been reconstructed from some written texts, while rudiments of the latter can only be retrieved from individual words and place-names.

Northern Russian dialects have been spoken by the Old-Believers, who arrived and settled in Podlachia, Suvalkia and later also in Prussian Masuria.

Native to the province of Pomerania and the vassal Lauenburg-Bütow Land (Lębork-Bytów) were Pomeranian dialects, which developed into what is called the Kashubian (regional) language, including its archaic and peripheral Slovincian dialect, extinct since the World War II.

One should not forget about Latin, which used to be the language of the Catholic Church, law, diplomacy and culture.

Other liturgical/canonical languages which could be heard in the multiconfessional Commonwealth included:

- Old-Church-Slavic – in Russian Orthodox and Old-Believers’ churches,

- Old-Armenian Grabar – in the Armenian Apostolic and later Armenian Catholic Church,

- Hebrew – the language of Judaism and Karaism (with time, the latter adopted also their ethnic language),

- Arabic – language of prayers and (in the past) writing of Tatars and Ottoman settlers

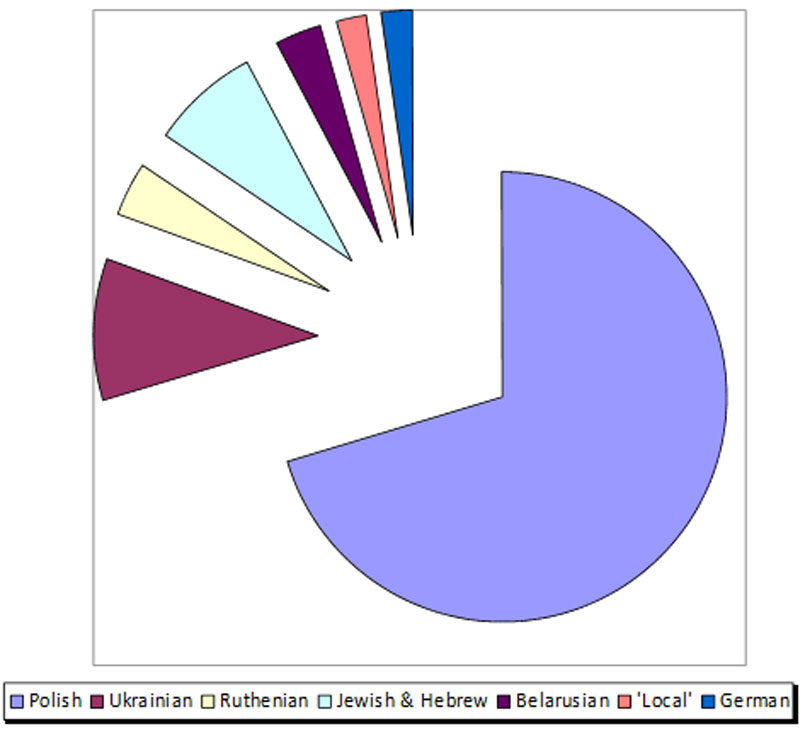

It was already during the II Republic of Poland that its linguistic landscape became restricted in its extent. Nonetheless, the interwar period saw Poland to still be a country of many ethnicities, religions and languages. Some of these languages were spoken by communities of hundreds of thousands, as the results of the 1931 General Census show. The population of Poland (which, in 1931, amounted to 31.9 million people) was (according to the declaration of one's native language) 69% Polish-speaking. Other languages spoken by Poland's citizens included:

| Ukrainian | 3.221.975 | 10,1% |

| Ruthenian | 1.219.647 | 3,8 % |

| Jewish | 2.489.034 | 7,8 % |

| Hebrew | 243.539 | 0,08% |

| Belarusian | 989.852 | 3,1 % |

| ‘Local’ | 707.088 | 2,2 % |

| German | 740.992 | 2,3 % |

| Russian | 138.713 | 0,04% |

| Lithuanian | 83.116 | 0,03% |

| Czech | 38.097 | 0,01% |

| other | 11.119 | |

| not declared | 39.163 |

It were exactly the non-standard varieties (as no standards have been established for them) that comprised the linguistic mosaic of the II Republic.

Languages in the II Republic - 1931 r.

Thus, a total of nearly 10 million citizens of interwar Poland spoke not Polish but a different language on a daily basis.

Following the end of WWII the People's Republic of Poland, and its citizens, found themselves in a completely different reality, a new linguistic one included. The borders were moved westwards. The German were transferred to Germany and Austria; Ukrainians and Lemkos to the Soviet Union and to the Recovered Territories. The Jewish and Gypsy peoples fell prey to the Nazi German murder machine. All this, along with massive external and internal migrations and the new policies taken up by the Polish government in cooperation with the USSR led to the country's linguistic and national unification. Minorities were something no longer discussed or written about during Stalin's reign. Only after the changes of 1956 the minority and languages policies mitigated. Schools which offered the teaching of the standardised varieties of the minority languages were founded - German, Jewish, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Lithuanian, Slovak, Czech and even Greek (for children of political refugees from Greece), they operated with newly published course books. Magazines in German, Yiddish and Hebrew, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Russian, Lithuanian, Czech and Slovak, or Romani were published. The government even allowed for Kashubian and Lemko publications, even though, at the time, these varieties were deemed mere dialects of Polish and Ukrainian respectively. A Greek and a Macedonian magazine were also published for the refugees from Greece. In different periods radio auditions were broadcast in Yiddish, German, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Lithuanian and Russian. In this new environment, the already small and dispersed minorities would be assimilated at an ever greater pace under the constant control of the government and without any language policy to protect them. During the communist period no statistical data/figures for ethnic or language minorities living in Poland were published or even known.

The political and social changes started in 1989 have brought significant developments in the situation of minority (language) communities in what was soon labeled as the III Republic of Poland. Numerous activities were undertaken with the intention of strengthening the presence of minorities in the public sphere. In order to specify and legally secure those political provisions, in 2005, the Polish Parliament passed the Act on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages: http://mniejszosci.narodowe.mac.gov.pl/mne/prawo/ustawa-o-mniejszosciac/tlumaczenia/6490,Tlumaczenia-Ustawy-o-mniejszosciach-narodowych-i-etnicznych-oraz-o-jezyku-region.html

2) significantly differs from the remaining citizens in its language, culture or tradition;

3) strives to preserve its language, culture or tradition;

4) is aware of its own historical, national community, and is oriented towards its expression and protection;

5) its ancestors have been living on the present territory of the Republic of Poland for at least 100 years;

6) identifies itself with a nation organized in its own state.

2. The following minorities shall be recognized as national minorities:

Belarusians; Czechs; Lithuanians; Germans; Armenians; Russians; Slovaks; Ukrainians; Jews

(http://www.msw.gov.pl/portal/pl/178/2958/Ustawa_o_mniejszosciach_narodowych_i_etnicznych_oraz_o_jezyku_regionalnym.html oraz http://mac.gov.pl/mniejszosci-i-wyznania)

2) significantly differs from the remaining citizens in its language, culture or tradition;

3) strives to preserve its language, culture or tradition;

4) is aware of its own historical, national community, and is oriented towards its expression and protection;

5) its ancestors have been living on the present territory of the Republic of Poland for at least 100 years;

6) does not identify itself with a nation organized in its own state.

4. The following minorities shall be recognized as ethnic minorities:

Karaims; Lemko; Roms; Tatars

2) different from the official language of that State; it shall not include either dialects of the official language of the State or the languages of migrants.

2. The Kashubian language shall be a regional language within the meaning of the Act (…)

Efforts are made to officially recognize Silesian and Wilamowicean as regional languages.

The results of two Censuses (carried out in 2002 and 2011) preliminarily revealed rough figures related to minority language use, although numerous doubts and ambiguities concerning the census methodology were reported by minority communities, sociologists and independent statisticians.

| Polish (exclusively) |

36.802.514 (98,06 %) |

| German | 196.841 |

| Kashubian | 52.665 |

| Silesian | 56.643 |

| Belarusian | 40.226 |

| Ukrainian | 21.155 |

| Romani | 15.657 |

| Russian | 12.125 |

| Lithuanian | 5.696 |

| Lemko | 5.605 |

| Czech | 1.226 |

| Slovak | 794 |

| Armenian | 321 |

|

Hebrew Yiddish |

207 36 |

| Tatar | 9 |

| Karaim | 0 |

These figures explicitly indicate how small and weak the heritage language communities in Poland became in the communist system.

| Polish | 37 815 606 |

| Silesian | 529 377 |

| Kashubian | 108.140 |

| German | 96.461 |

| Belarusian | 26.448 |

| Ukrainian | 24.539 |

| Russian | 19.805 |

| Romani | 14.468 |

| Lemko | 6.279 |

| Lithuanian | 5.303 |

| Armenian | 1.847 |

| Czech | 1.451 |

| Slovak | 765 |

| Hebrew / Yiddish | 321 / 90 |

| Tatar | 9 |

| Karaim | 0 |

| Polish-Belarusian borderland dialect | 669 |

| Ruthenian (‘ruski’) | 626 |

| Belarusian dialect / ‘simple’ language | 549 |

| Belarusian-Ukrainian dialect | 516 |

| Highlanders’ dialect | 604 |

Endangered minority languages in Poland

Of course, the fact that a language is a minority language does not immediately mean that it is also endangered. There is no way of telling whether there is a number threshold for minority language users deciding on whether the language is (still) safe or (already) endangered. The factor of outmost importance which is the decisive one is the lack of or the disruption of the language's intergenerational transmission.

- very small languages (1-100 thousand speakers); Belarusian, Lithuanian, Lemko, Romani, Russian, Ukrainian;

- microlanguages (≤ 1000 speakers): Czech, Slovak, (Hebrew and) Yiddish.

The scale for assessing the extent of language endangerment agreed upon by and employed by UNESCO discern six levels of endangerment based on the criterion of intergenerational transmission.

http://pl.languagesindanger.eu/book-of-knowledge/language-endangerment

| Degree of Endangerment | Grade | Speaker Population |

|---|---|---|

| safe | 5 | the language is used by all ages, from children up |

| unsafe / vulnerable | 4 |

the language is used by some children in all domains / it is used by all children in limited domains (e.g. home) or it is used by all children in limited domains (e.g. home) |

| definit(iv)ely endangered | 3 |

the language is used mostly by the parental generation and up; children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home |

| severely endangered | 2 | the language is used mostly by the grandparental generation and up; while the parent generation may understand it, they do not speak it to children or among themselves |

| critically endangered | 1 |

the language is used mostly by very few speakers, of great-grandparental generation (and they speak the language partially and infrequently) |

| extinct | 0 | there is no one who can speak or remember the language = there exists no speaker |

The only languages that can be seen as safe are the standard languages which are taught in schools for ethnic minorities. One example is the standard variety of Lithuanian (which is both a subject and the language of instruction), another is German and Ukrainian due to their international prestige (although the position of these languages as the language of the German and Ukrainian minorities may be compromised).

About the project

The past and present territories of the Republic are home to many languages which are spoken by a varied, often low, number of users. These languages have not yet been documented and their existence is endangered. These languages constitute an important element of the linguistic heritage of Poland. Linguistically the territory of the Republic of Poland has always been and still is a territory of co-existence of many language communities, and, conversely, an area of mutual linguistic contact (regardless of the quantity and quality of these contacts).

It was over a century ago since it has been suggested to document and research the less known (and endangered) non-standard language varieties spoken in the area of the Polish language's dominance and influence.

Documenting endangered languages is one the key research subjects in the field of linguistics today worldwide. That is why numerous projects are realized thanks to the funding of governmental budgets and organizations interested in protecting cultural heritage. In recent years, many of these projects, including this one, can be realized thanks to the Polish Ministry of Science’ grant within the Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki. The field's research development also constitutes an important drive for the development of linguistics as a whole, the employment of leading-edge technologies and, in the future, the usage of the newly acquired knowledge in multidisciplinary research.

The selection of languages and materials

The presented documentation database does not directly include the varieties of Polish that are unequivocally deemed as dialects and sub-dialects of Polish. Nonetheless, the presence of certain border-line varieties presented in our web portal may evoke a lively discussion, a fact which we have been aware of...

Some of the language varieties used in Poland, which were considered dialects of the Polish in the past, are attempting or have succeeded in raising their linguistic status. For example, Kashubian has been officially acknowledged by the Polish language policy a few years ago and currently enjoys the legislature which is offered to "regional languages". The question of offering such a status to the dialects of Silesian and Wilamowicean is a current one.

Our project, thus, did not focus on the dialects of the Polish language nor on the standard language varieties that the (present and past) national minorities inhabiting the territories of the Republic of Poland can identify with (e.g. the Ukrainian, Belarusian, Lithuanian, Latvian, German, Czech and Slovak languages, among others).

The main criterion for choosing the given language varieties for their documentation and archiving was their co-existence on the territories of the Republic (or, more suitably, Republics) of Poland and, also, more importantly, the fact that they were all affected by the language contacts with Polish in modern times.

The following languages have been chosen for the first detailed analyses as well as for the purpose of launching this database:

- Latgalian

- Polish Yiddish

- Wilamowicean / Wymysorys

- Hałcnovian as the remnant of the Bielitz-Bialaer Sprachinsel.

The choice, range and content of our web portal are dynamic and, as such, will likely be enriched and expanded over time.

Beata Mikołajczyk

Nicole Nau

Marek Dolatowski

Michael Hornsby

Maciej Karpiński

Jarosław Weckwerth

Tomasz Wicherkiewicz

Justyna Benedykczak, Katarzyna Budasz-Organista, Julian Candrowicz, Bartłomiej Chromik, Jacek Cieślewicz, Katarzyna Dulat, Prof. Ewa Geller, Wojciech Gutkiewicz, Paulina Handke, Danuta Hanusz, Anna Jorroch, Wojciech Klessa, Dr. Agata Kondrat, Mirosław Koziarski, Tymoteusz Król 'fum-Dökter', Arkadiusz Lechocki, Prof. Lideja Leikuma, Santa Logina, Justyna Majerska 'fum-Biba-Jåśkja', Prof. Alfred F. Majewicz, Anna Matuszek, Jacek Milewski, Aleksandra Mrozińska, Robert Piechocki, Dr. Alois Rosner, Piotr Szczepankiewicz, Jacek Swędrowski, Anna Szombierska, Heather Valencia, Radosław Wójtowicz, Andrzej Żak, Anna Żebrowska;

and last but not least – to all our Informants – the native speakers of endangered heritage languages:

Serdecznie Dziękujemy !

Cīši lels Paļdis !

! א שיינעם דאַנק

Hacagan Göt bycoł dy'ś !

Got betsohlt's !