German dialects in Silesia

Name

Endonyms

Schläsisch, Schläs’sch, Schläsche Sproache, or just Schläschin are endonyms denoting the whole of the Silesian German dialect group; of course, the dialects themselves have their own names, e.g.:- Highland dialect - Gebergsschläsch

- Glatz/Kladsko/Kłodzko dialect – Gleetzisch or Pauersch ('Peasants' dialect)

- the Diphthongizing dialect, also known as Neiderländisch

- Herbal(ists') dialect (Kräutermundart)

- dialect of the Brieg/Brzeg & Grottkau/Grodków region - Mundart des Brieg-Grottkauer Landes

- Breslau/Wrocław dialect - Breslauisch

- Upper Silesian dialect - Oberschläsch

- Upper Lusatian dialect - Äberlausitzer Mundoart

Exonyms

The collective term denoting the Silesian German dialects in Standard German is Schlesisch and Gesamtschlesisch. It should be noted, however, that within the German-speaking area the word Schlesisch can also be used to relate to the Silesian dialect of Polish (Wasserpolnisch, Schlonsakisch, Szlonzokian - Ethnologue code szl), whose speakers are actively pursuing to elevate its official linguistic status.The Ethnologue database employs the term of Lower Silesian; the other possible name is Upper Schlesisch. The sli code denotes the Silesian German dialect group in the ISO-639-3 standard. They are described using the 6a stage, meaning "vigorous", a stage ascribed to living languages. What is important to remember, however, is that these dialects are exclusively used by elderly people within a family context and are not transferred to the younger generations - which is why they are threatened with language death. Despite the fact that they have a mere 22,900 speakers they were not included in UNESCO's list of endangered languages.

History and geopolitics

Location in the Republic of Poland

The I and II Republic

There is no precise data concerning the localization of the German Silesian dialects within the timeframe of the I Republic. The data corresponding to this area is often inexact (cf. von Unwerth 1908: 1 Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

, Jungandreas 1928: 12

, Jungandreas 1928: 12 Jungandreas 1928 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jungandreas 1928 / komentarz/comment/r / Jungandreas, Wolfgang 1928. Beiträge zur Erforschung der Besiedlung Schlesiens und zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der schlesischen Mundart. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

, Menzel 1976: 17

, Menzel 1976: 17 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

) which is why it seems sensible to amalgamate all available reference works and chart an area where these dialects were used in the times of the I and II Polish Republic.

) which is why it seems sensible to amalgamate all available reference works and chart an area where these dialects were used in the times of the I and II Polish Republic.

Map of the Silesian German dialects. [map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, based on: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/Schlesien_Karte_Dialekte_Vorl%C3%A4ufig.png]

Prior to the Second World War, the Silesian German dialects constituted the largest and most concentrated group of East Middle German dialects (Księżyk 2008: 20, 21

Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment/r /

Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment/r / Księżyk, Felicja 2008. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Kostenthal. Geschichte und Gegenwart. Berlin: trafo Verlag.

). They spread not only throughout Silesia but also outside of its borders: in the West they shifted towards the Lusatian dialect and bordered with the Upper Saxon dialect. The dialects also spanned across areas beyond the Lusatian dialect such as Schwiebus/Świebodzin, Züllichau/Sulechów and Crossen an der Oder/Krosno Odrzańskie. In the South, the Silesian German dialects reached the Sudety mountains, the northern reaches of Bohemia (area of Liberec), Northern Moravia and even Kuhländchen/Kravařsko region. They were also spoken in the eastern language enclaves of Schönwald/Bojków, Anhalt-Gatsch/Hołdunów-Gać and Bielitz-Biala/Bielsko-Biała by the German populace of Lesser Poland, to a limited extent even in Cracow/Krakau/Kraków and, for example, in Krzemienica in Galicia. The area of influence of the Silesian German dialects included the Posen province as well, which experienced an influx of Silesian settlers up until the 17th century. The High Prussian dialect spoken in Warmia and Masuria did show some resemblance to Silesian German as well (Księżyk 2008: 20, 21

). They spread not only throughout Silesia but also outside of its borders: in the West they shifted towards the Lusatian dialect and bordered with the Upper Saxon dialect. The dialects also spanned across areas beyond the Lusatian dialect such as Schwiebus/Świebodzin, Züllichau/Sulechów and Crossen an der Oder/Krosno Odrzańskie. In the South, the Silesian German dialects reached the Sudety mountains, the northern reaches of Bohemia (area of Liberec), Northern Moravia and even Kuhländchen/Kravařsko region. They were also spoken in the eastern language enclaves of Schönwald/Bojków, Anhalt-Gatsch/Hołdunów-Gać and Bielitz-Biala/Bielsko-Biała by the German populace of Lesser Poland, to a limited extent even in Cracow/Krakau/Kraków and, for example, in Krzemienica in Galicia. The area of influence of the Silesian German dialects included the Posen province as well, which experienced an influx of Silesian settlers up until the 17th century. The High Prussian dialect spoken in Warmia and Masuria did show some resemblance to Silesian German as well (Księżyk 2008: 20, 21 Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment/r /

Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment/r / Księżyk, Felicja 2008. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Kostenthal. Geschichte und Gegenwart. Berlin: trafo Verlag.

).

).The base dialect is comprised of the Highland dialect (Gebirgsmundart), Glatz/Kłodzko/Kladsko dialect (Glätzisch) and Lusatian-Silesian dialect. Its border was comprised of the towns of Sagan/Żagań, Sprottau/Szprotawa, Haynau/Chojnów, Liegnitz/Legnica, Lorenzdorf/Ławszowa, Kanth/Kąty Wrocławskie oraz the territories east of Bernstadt/Bierutów (Ger. ) (Kryszczuk 1999: 80

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

).The borders of the Highland dialect (Gebirgsmundart) ran through Friedeberg/Mirsk, Greiffenberg/Gryfów, Löwenberg/Lwówek, Goldberg/Złotoryja, Koischwitz/Kostkowice, Amsdorf/Miłków, Groß Tinz/Tyniec Legnicki, Fürstenstein/Książ, Zobten/Sobótka, Strehlen/Strzelin, Ottmachau/Otmuchów, Neisse/Nysa, through Oberglogau/Głogówek to Leobschütz/Głubczyce up until the border of the province (Kryszczuk 1999: 80

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). The Highland dialect was also inclusive of that of Kuhländchen, which was used in a small area at the source of the river Odra. Kuhländchen is the German name for the region of Kravařsko located in Moravia (cf. Kryszczuk 1999: 80

). The Highland dialect was also inclusive of that of Kuhländchen, which was used in a small area at the source of the river Odra. Kuhländchen is the German name for the region of Kravařsko located in Moravia (cf. Kryszczuk 1999: 80 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). The Glatz/Kladsko/Kłodzko dialect was a variety of the Highland dialect. It was used in the former County of Glatz/Kladsko and its vicinity. The Upper Silesian dialect was spoken in Upper Silesia, between Oppeln/Opole, Ratibor/Racibórz and Kattowitz/Katowice, up until the borders of the voivodeship. The borders of the Lusatian-Silesian dialect (Lausitzisch-Schlesisch) ran through Striegau/Strzegom, Jauer/Jawor, Goldberg/Złotoryja and Bunzlau/Bolesławiec (von Unwerth 1908: 8

). The Glatz/Kladsko/Kłodzko dialect was a variety of the Highland dialect. It was used in the former County of Glatz/Kladsko and its vicinity. The Upper Silesian dialect was spoken in Upper Silesia, between Oppeln/Opole, Ratibor/Racibórz and Kattowitz/Katowice, up until the borders of the voivodeship. The borders of the Lusatian-Silesian dialect (Lausitzisch-Schlesisch) ran through Striegau/Strzegom, Jauer/Jawor, Goldberg/Złotoryja and Bunzlau/Bolesławiec (von Unwerth 1908: 8 Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

).

).

Lusatian-Silesian dialects [łużycko-śląskie] on the G. Maurmann's map of German dialects - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz

The Upper Lusatian dialect was spoken on the territories of Northern Bohemia which bordered the Silesian and Saxon parts of Lusatia, and whose borders ran from Görlitz/Zgorzelec up until the area west of Sagan/Żagań and Grünberg/Zielona Góra (cf. von Unwerth 1908: 89

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

).

).Jungandreas (1928: 250

Jungandreas 1928 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jungandreas 1928 / komentarz/comment/r / Jungandreas, Wolfgang 1928. Beiträge zur Erforschung der Besiedlung Schlesiens und zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der schlesischen Mundart. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

) states the Diphtongizing dialects (Diphtongierungsmundarten) can be divided into two groups - the first encompassed the territory beginning with the suburbs of Grünberg/Zielona Góra, through Sprottau/Szprotawa, Breslau/Wrocław, Trebnitz/Trzebnica up until Oels/Oleśnica and Militsch/Milicz. The second group was spoken from Glogau/Głogów to Lüben/Lubin, Wohlau/Wołów and Trachenberg/Żmigród. The Herbal(ists') dialect can be also counted among the ranks of Diphthongizing dialects. It was used in the vicinity of Breslau/Wrocław, near Neumarkt/Środa Śląska, Liegnitz/Legnica, Lüben/Lubin, and Goldberg/Złotoryja. In the area between the Herbal(ists') dialect in the South and the Highland dialect in the West, another dialect was spoken around Brzeg/Brieg, Namslau/Namysłów and Grottkau/Grodków, the Brieg-Grottkauer Mundart (Kryszczuk 1999: 82

) states the Diphtongizing dialects (Diphtongierungsmundarten) can be divided into two groups - the first encompassed the territory beginning with the suburbs of Grünberg/Zielona Góra, through Sprottau/Szprotawa, Breslau/Wrocław, Trebnitz/Trzebnica up until Oels/Oleśnica and Militsch/Milicz. The second group was spoken from Glogau/Głogów to Lüben/Lubin, Wohlau/Wołów and Trachenberg/Żmigród. The Herbal(ists') dialect can be also counted among the ranks of Diphthongizing dialects. It was used in the vicinity of Breslau/Wrocław, near Neumarkt/Środa Śląska, Liegnitz/Legnica, Lüben/Lubin, and Goldberg/Złotoryja. In the area between the Herbal(ists') dialect in the South and the Highland dialect in the West, another dialect was spoken around Brzeg/Brieg, Namslau/Namysłów and Grottkau/Grodków, the Brieg-Grottkauer Mundart (Kryszczuk 1999: 82 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

).It should be mentioned, of course, that the constant influx of new settlers to Silesia resulted in the phenomenon where several different dialects could be spoken in one village (von Unwerth 1908: 80

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

).

).People's Republic of Poland period

There is no official data concerning the distribution of Silesian German dialects during the communist period. The change of borders following the end of the II World War and forced resettlements of German people from the territory of Poland led to yet another admixture of Silesia's population and, thus, its languages. Excluding the years 1950-1959, the use of the German language (even its literary standard) was banned in Lower Silesia (cf. Wiktorowicz 1997: 1956 Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiktorowicz, Józef 1997. „Polnisch-Deutsch“, w: Goebl, Hans i in.(red.) Kontaktlinguistik. Contact linguistics. Linguistique de contact. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. 1594-1600.

). National minorities, however, were recognized. Since 1956 most of them became represented by a number of different organizations. Meanwhile German authors published their works on Silesian German dialects (Bellmann 1965

). National minorities, however, were recognized. Since 1956 most of them became represented by a number of different organizations. Meanwhile German authors published their works on Silesian German dialects (Bellmann 1965 Bellmann 1965 / komentarz/comment/r /

Bellmann 1965 / komentarz/comment/r / Bellmann, Günter & Erich Ludwig Schmitt 1965. Schlesischer Sprachatlas. 2. Band. Wortatlas von Günter Bellmann. Marburg: N.G. Elwert Verlag.

, 1967

, 1967 Bellmann 1967 / komentarz/comment/r /

Bellmann 1967 / komentarz/comment/r / Bellmann, Günter, Wolfgang Putschke & Werner Veith 1967. Schlesischer Sprachatlas 1. Band Laut- und Formenatlas von Günter Bellmann unter Mitarbeit von Wolfgang Putschke und Werner Veith. Marburg: N.G. Elwert Verlag.

, Bluhme 1964

, Bluhme 1964 Bluhme 1964 / komentarz/comment/r /

Bluhme 1964 / komentarz/comment/r / Bluhme, Hermann 1964. Beitrag zur deutschen und zur polnischen Mundart im oberschlesischen Industriegebiet. Unter bes. Berücksichtigung phonometrischer Methoden. Den Haag.

, Menzel 1976

, Menzel 1976 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

, Mitzka 1953

, Mitzka 1953 Mitzka 1953 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1953 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1953. Deutscher Wortatlas. Band II. Gießen: Wilhelm Schmitz Verlag.

, Mitzka 1963-1965

, Mitzka 1963-1965 Mitzka 1963-1965 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1963-1965 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1963-1965. Schlesisches Wörterbuch. Band 1-3. Berlin: de Gruyter.

, Veith 1971

, Veith 1971 Veith 1971 / komentarz/comment/r /

Veith 1971 / komentarz/comment/r / Veith, Werner H. 1971. Die lexikalische Stellung des Nordschlesischen. In ostmittel- und gesamtdeutschen Bezügen. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Weinbauterminologie. Köln: Böhlau Verlag.

).

The map below depicts the difference between pre-WWII German-speaking Silesia and post-WWII Silesia.

).

The map below depicts the difference between pre-WWII German-speaking Silesia and post-WWII Silesia.%20j%C4%99zyka%20niemieckiego%20w%20Europie%20%C5%9Brodkowej%20po%201950.jpg)

Distribution of German dialects in Central Europe after 1950. [source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heutige_deutsche_Mundarten.PNG]

Other locations

Approximately at the beginning of the 20th century the Silesian German dialects were spoken in the Silesian part of Lusatia, the Saxon part of Upper Lusatia and the bordering Northern reaches of the Czech Republic. The Highland dialect was used in the area beginning at the river Úpa/Aupa in the Czech Republic, through the towns of Horní Maršov/Marschendorf and Svoboda nad Úpou/Freiheit, and ending with where Czech bagan to be spoken. East of Trutnov/Trautenau) and Žacléř/Schatzlar), people would use the Highland dialect in its most pure form (von Unwerth 1908: 89 Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

). Another dialect spoken near Trutnov, in the vicinity of the town of Brumov/Braunau), was the so called Mundart des Braunauer Ländchens (von Unwerth 1908: 91

). Another dialect spoken near Trutnov, in the vicinity of the town of Brumov/Braunau), was the so called Mundart des Braunauer Ländchens (von Unwerth 1908: 91 Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

). The Kladsko/Glatz/Kłodzko dialect spoken in the Northern parts of the County of Kladsko bordered with yet another dialect east and north of Landeck/Lądek Zdrój. This dialect was used in the region of the Opawa river (Oppaland) and Northern Moravia (von Unwerth 1908: 92

). The Kladsko/Glatz/Kłodzko dialect spoken in the Northern parts of the County of Kladsko bordered with yet another dialect east and north of Landeck/Lądek Zdrój. This dialect was used in the region of the Opawa river (Oppaland) and Northern Moravia (von Unwerth 1908: 92 Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

), where Kravařsko/Kuhländchen had its own distinct dialect as well (von Unwerth 1908: 93

), where Kravařsko/Kuhländchen had its own distinct dialect as well (von Unwerth 1908: 93 Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r /

Unwerth 1908 / komentarz/comment/r / Unwerth, Wolf von 1908. Die schlesische Mundart in ihren Lautverhältnissen grammatisch und geographisch dargestellt. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

).

).History and origins

German settlement in Poland was initiated by princes of the Piast dynasty, the Catholic Church, Polish magnates and the knighthood (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 42 Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

). Historians, however, are in no agreement about the exact date of the first German settlement to Silesia. It is by convention that the date 1175 is ascribed to this phenomenon; it is then that Prince Bolesław I the Tall granted colonial rights to the German monastery in Leubus/Lubiąż (Kryszczuk 1999: 34

). Historians, however, are in no agreement about the exact date of the first German settlement to Silesia. It is by convention that the date 1175 is ascribed to this phenomenon; it is then that Prince Bolesław I the Tall granted colonial rights to the German monastery in Leubus/Lubiąż (Kryszczuk 1999: 34 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). However, it was proved that this document had been forged and, as such, it is not a reliable source of information (Jungandreas 1928: 26

). However, it was proved that this document had been forged and, as such, it is not a reliable source of information (Jungandreas 1928: 26 Jungandreas 1928 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jungandreas 1928 / komentarz/comment/r / Jungandreas, Wolfgang 1928. Beiträge zur Erforschung der Besiedlung Schlesiens und zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der schlesischen Mundart. Breslau: Verlag von M. & H. Marcus.

).

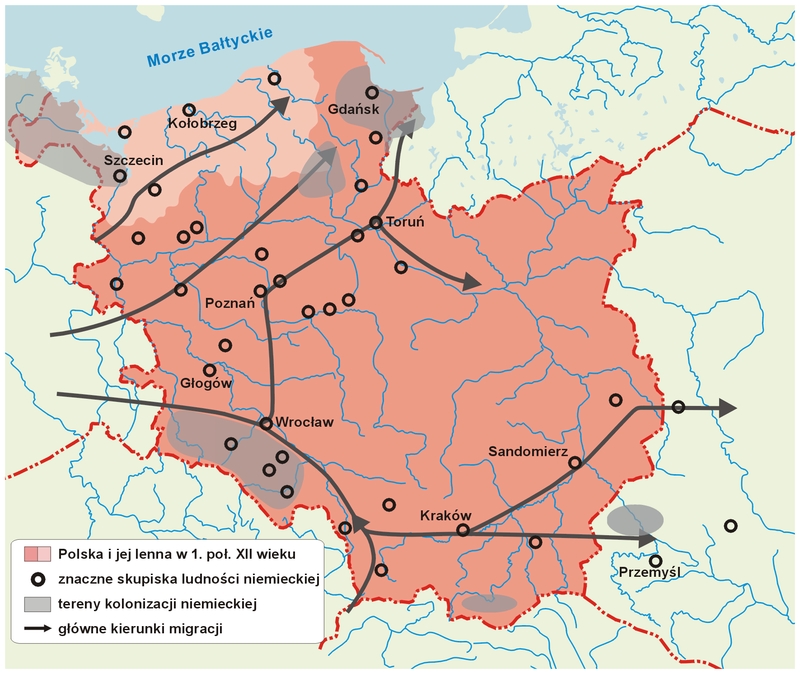

).The period of Fragmentation that befell Poland after 1138 was undoubtedly a factor that benefited German colonisation on Polish territory. After all, any superior authority over the whole country ceased to exist; the Crusades also exerted influence on the process of migration. While it is believed that had one of the province princes unified the whole of Poland, the colonisation process would not have been so severe in its results. It should be noted, however, that this phenomenon was not a march of history completely independent of the will of the Polish people. The political situation of Poland by the end of the 12th century and the events in Silesia (after Władysław II The Exile was expelled and Silesia, Opole and Lubusz were granted to his sons, they decided to pay tribute to the German ruler Frederick I Barbarossa in 1173) opened two possibilities for the expansion of the German language: one in the North, through Pomerania; the second in the South, in Silesia. This is illustrated by the map below (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 41, 42, 43

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

).

).

Germanic colonisation in the Middle Ages (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, based on: Brzezina 1989: 22

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

).

).Having been heavily influenced by German culture, Bolesław I the Tall brought the first German monks (Cistercians from the monastery of Pforta in Saxony) to Leubus/Lubiąż in 1163. Around that time, the Benedictine monks from Breslau/Wrocław's St. Vincent Abbey were replaced with German Premonstratensians, and a German named Cyprian was appointed the Abbey's bishop for the period 1193 to 1201. He would, then, establish relations with the town of Bamberg where Bolesław I the Tall's brother, Conrad, was bishop between 1202 and 1203. This is how Polish ground was prepared for further German colonisation, clearing the decks for German influence in Silesia (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 43, 44

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

).

).The process of settlement boomed especially in the 13th and 16th centuries, mostly due to the desolation and depopulation that the Tatar invasions had caused. Approximately 150-180 thousand settlers came to Lower Silesia following these events. They had originated in Western Europe, mainly in Thuringia and Saxony but also in Brandenburg, Hess, Franconia, Bavaria and Austria. Many of the towns of Lower Silesia became Germanized - rural Silesia, however, remained Polish in nature. The emigration of German settlers was halted by the outbreak of plague in the middle of the 14th century (Kryszczuk 1999: 34, 35

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). From a dialectological perspective it is extremely important to acknowledge the colonial policies of that time. The standard process would be to surround German-speaking towns with a ring of German villages. The result was a self-sufficient German-language enclave (Brzezina 1989: 45

). From a dialectological perspective it is extremely important to acknowledge the colonial policies of that time. The standard process would be to surround German-speaking towns with a ring of German villages. The result was a self-sufficient German-language enclave (Brzezina 1989: 45 Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

).

).In the 13th century, the Germanized Silesia began to "supply" Pomerania with its settlers. Some of them decided to leave Silesia due to a dispute with the Wrocław bishop over tithe fees. Initially, these settlers were attributed to play a major role in the colonisation process of the areas north of Silesia. Hence, the dialect north from Allenstein/Olsztyn was termed Breslausch, i.e. the Wrocław dialect (Brzezina 1989: 20

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

). The map below shows the distribution of this dialect.

). The map below shows the distribution of this dialect.

Breslausch as one of the East Middle German dialects [source unknown]

The development of the Polish and German languages in Upper and Lower Silesia was significantly connected to the influx of settlers whose numbers rose to about 400 thousand by the 14th century. As the first stage of colonisation ended by the 14th century, the whole of Lower Silesia was heard speaking Slavic and German dialects; by the 15h century the region was completely bilingual. Contrary to the situation in Silesia, the linguistic environment of Bohemia was clearly separated and divided (Kryszczuk 1999: 34, 38

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

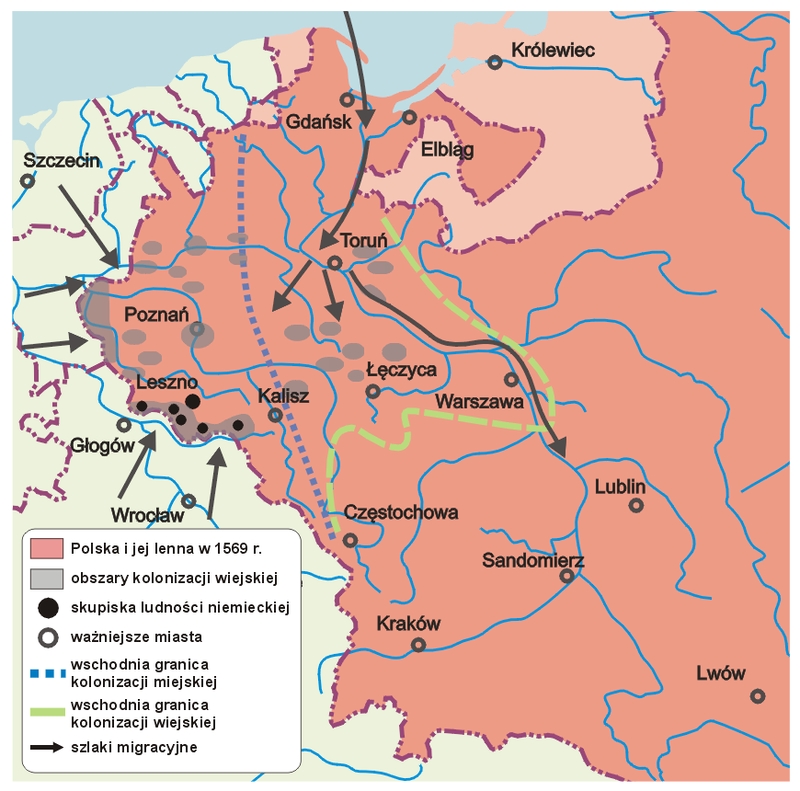

The course and directions of the second German colonisation are presented in the map below.

).

The course and directions of the second German colonisation are presented in the map below.

The Second Germanic colonisation - 16h century (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, based on: Brzezina 1989: 25

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

)

)This second wave of colonisation began in the 16h century, again by the initiative of Polish magnates and gentry. As a matter of fact, not many new people settled in Silesia at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. It was the events that took place at that time in Germany that were decisive for the future German migrations to Poland (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 152

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

). These migrations were affected by two factors: firstly, religion - the Reformation began by Martin Luther, the simultaneous increase of power of the Catholic Habsburg dynasty in Germany, and the resulting religious tensions and persecutions of protestants in the Catholic lands of the Germany; secondly, economy - the overpopulation of Western and Southern Germany caused by economic development, the worsening of the social status of small land owners since the German Peasants' Wars of 1524-1525 and the oppression towards the kingdom's subjects, particularly in Brandenburg and Prussia. Driven by the need to leave their land, the German people migrated to Poland hoping for greater religious and economic freedom. It is, thus, not until the year 1600 that a significant influx of new settlers could be observed (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 151, 152

). These migrations were affected by two factors: firstly, religion - the Reformation began by Martin Luther, the simultaneous increase of power of the Catholic Habsburg dynasty in Germany, and the resulting religious tensions and persecutions of protestants in the Catholic lands of the Germany; secondly, economy - the overpopulation of Western and Southern Germany caused by economic development, the worsening of the social status of small land owners since the German Peasants' Wars of 1524-1525 and the oppression towards the kingdom's subjects, particularly in Brandenburg and Prussia. Driven by the need to leave their land, the German people migrated to Poland hoping for greater religious and economic freedom. It is, thus, not until the year 1600 that a significant influx of new settlers could be observed (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 151, 152 Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

). This colonisation led to another phenomenon - the emigration of the German populace of Silesia (mainly the urban populace, particularly the craftsmen) to South-Eastern Greater Poland. These people were Protestants who felt oppressed by Ferdinand II and began their journey as early as 1630. Since 1635, a mass German Protestant emigration from Silesia was prompted by the Emperor's order (they were to leave the territory within 3 years). The magnates of Greater Poland saw the opportunity to acquire a new workforce and seized it by persuading these settlers to come to Poland (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 157, 158

). This colonisation led to another phenomenon - the emigration of the German populace of Silesia (mainly the urban populace, particularly the craftsmen) to South-Eastern Greater Poland. These people were Protestants who felt oppressed by Ferdinand II and began their journey as early as 1630. Since 1635, a mass German Protestant emigration from Silesia was prompted by the Emperor's order (they were to leave the territory within 3 years). The magnates of Greater Poland saw the opportunity to acquire a new workforce and seized it by persuading these settlers to come to Poland (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 157, 158 Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

).

In the 17th and 18th centuries German was virtually not spoken in Upper Silesia. The language used by peasants and industrial workers was the Slavic variety called Wasserpolnish, which was definitely more similar to the Polish language despite the noticeable numerous German influences (Eser 2000: 297

).

In the 17th and 18th centuries German was virtually not spoken in Upper Silesia. The language used by peasants and industrial workers was the Slavic variety called Wasserpolnish, which was definitely more similar to the Polish language despite the noticeable numerous German influences (Eser 2000: 297 Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

). It was at that time that the second wave of German colonisation had ended, with some variation depending on the given Polish province (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 166

). It was at that time that the second wave of German colonisation had ended, with some variation depending on the given Polish province (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 166 Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

). Since 1628, after being driven out of Lower Silesia by the Habsburg dynasty and its Counter-Reformation initiatives, Evangelical drapers would found towns south of Poznań and develop existing ones, e.g. Rawicz/Rawitsch, Bojanowo and Zduny ([Broken #894]Kauder 1940: VIII).

). Since 1628, after being driven out of Lower Silesia by the Habsburg dynasty and its Counter-Reformation initiatives, Evangelical drapers would found towns south of Poznań and develop existing ones, e.g. Rawicz/Rawitsch, Bojanowo and Zduny ([Broken #894]Kauder 1940: VIII).During the First Partition of Poland, Prussia and Austria implemented a colonial policy on the lands they had seized. Thanks to Frederick the Great a German language enclave was established in 1770 in Hołdunów/Anhalt in South-Eastern Upper Silesia. Following 1772, over 7000 German farmers were invited to settle there ([Broken #894]Kauder 1940: IX). The settlers comprised of people from various High German territories. During that period the Polish language was removed from the curricula of schools, from administration and Church services. In its place, the local population became obligated to learn German in schools which, in the end, led to the development of bilingualism on those territories which were originally Polish (Wiktorowicz 1997: 1595

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiktorowicz, Józef 1997. „Polnisch-Deutsch“, w: Goebl, Hans i in.(red.) Kontaktlinguistik. Contact linguistics. Linguistique de contact. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. 1594-1600.

). German peasantry from Silesia would normally use their Silesian dialect. For the purpose of communication with their Polish neighbours they would borrow the necessary words (Kryszczuk 1999: 51

). German peasantry from Silesia would normally use their Silesian dialect. For the purpose of communication with their Polish neighbours they would borrow the necessary words (Kryszczuk 1999: 51 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). The ethnic structure of Silesia was in constant state of flux due to the continuous immigration of German settlers. In 1786 Frederick II brought another 120 thousand colonists to his newly conquered lands (Kryszczuk 1999: 48

). The ethnic structure of Silesia was in constant state of flux due to the continuous immigration of German settlers. In 1786 Frederick II brought another 120 thousand colonists to his newly conquered lands (Kryszczuk 1999: 48 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). The map below depicts the areas of colonisation under the Partitions' period. The colonisation process was led by the House of Hohenzollern from Prussia: Frederick William II, Frederick William I and Frederick the Great. In Austria, it was the Habsburg dynasty and the following rulers that were responsible: Joseph II, Maria Theresa and Francis I (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 174, 183, 184, 188

). The map below depicts the areas of colonisation under the Partitions' period. The colonisation process was led by the House of Hohenzollern from Prussia: Frederick William II, Frederick William I and Frederick the Great. In Austria, it was the Habsburg dynasty and the following rulers that were responsible: Joseph II, Maria Theresa and Francis I (Kaczmarczyk 1945: 174, 183, 184, 188 Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kaczmarczyk 1945 / komentarz/comment/r / Kaczmarczyk, Zdzisław 1945. Kolonizacja niemiecka na wschód od Odry. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Zachodniego.

).

).

Frederick-the-Great's and Joseph II-the-Emperor's colonisation policy (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Brzezina 1989: 29

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

)

)The 1815's delimitation of European borders limited the flow of the East European drapery markets. Drapers from Poznań, thus, were forced to leave their current homes and make way to the North or South of Poland. In Silesia they founded a number of small settlements. Since 1818 seamsters from borderline areas of Silesia, Saxony and Bohemia would also settle in the Kingdom of Poland. Most of them were Catholic, whereas the drapers were exclusively Evangelical. They inhabited, for example, the towns of: Łódź/Lodz, Pabianice/Pabianitz, Tomaszów/Tomaschow. The amalgamation of Low German and (mainly) Silesian linguistic influences led to the development of a kind of Lodz German ([Broken #894]Kauder 1940: X). The 19th century was also a period when German settlers immigrated to Upper Silesia due to the rampant development of the mining industry. However, the miners that began to live there often came from a poor and uneducated environment, and so it was necessary to hire managerial staff, civil servants and experts from Western Germany. Due to the development of industry the population numbers rose by over a hundredfold since 1781 which brought about the establishment of large cities such as Katowice/Kattowitz and Królewska Huta/Königshütte (later renamed in Polish as Chorzów). German culture was visible in Upper Silesia even in the days of medieval colonisation, especially in the style of architecture, the ways of dressing and customs ([Broken #894]Kauder 1940: XII).

The strong and continuous influx of administrative officials, teachers and craftsmen from German-speaking areas, Lower Silesia in particular, since the end of the 19th century greatly contributed to the Germanization of Upper Silesian towns. A part of the Polish-speaking autochthonous populace also took part in this process; aspiring to raise their social status they began to use German within the public sphere. That is how a Silesian variety of an everyday German language began to spread over Upper Silesia. It was characterised by a large number of borrowings from Polish; and vice versa, the variety became a source of German borrowings into Silesian Polish dialects (see: Morciniec 2002

Morciniec 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Morciniec 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Morciniec, Norbert 2002. ”Wieloetniczność w historii Śląska na przykładzie polsko-niemieckich stosunków językowych”, w: Silesia Polonica. I Kongres Germanistyki Wrocławskiej. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. 27-35 [http://www.morciniec.eu/pl.php?id=4&view=2].

).

).Following the restitution of the Polish State in 1918, a high percentage of Germans still inhabited its Western provinces. Additionally, there still existed a number of isolated German language enclaves (Wiktorowicz 1997: 1596

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiktorowicz, Józef 1997. „Polnisch-Deutsch“, w: Goebl, Hans i in.(red.) Kontaktlinguistik. Contact linguistics. Linguistique de contact. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. 1594-1600.

). In 1919, Silesia was divided into two provinces: Lower and Upper Silesia. The Southern part was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. After the I World War the Polish government postulated that this region should be included within Polish borders due to the fact that the population of Upper Silesia spoke Polish. The plan was never realized because of numerous protests put forward by German diplomacy. The years 1919 and 1920 saw two Silesian uprisings which were supported by the Polish side but which became thwarted by voluntary paramilitary groups (known as Freikorps). On the 20th of March 1921 the Upper Silesia plebiscite took place. Later that year in May, the Third Silesian Uprising broke out and, as a consequence, the League of Nations advised to divide Upper Silesia. As of 1922, the Republic of Poland received the Eastern part of Upper Silesia, along with Tarnowskie Góry (Ger. Tarnowitz), Katowice (Ger. Kattowitz) and Królewska Hutą (Ger. Königshütte, today known as Chorzów), while the German Weimar Republic incorporated its Western part with the cities of Gliwice, Bytom and Zabrze. The national minorities that remained on either side of the border were granted many exclusive rights during the Interwar Period. Their bilingualism, however, was an obstacle on determining their national identities (Eser 200: 299, 300

). In 1919, Silesia was divided into two provinces: Lower and Upper Silesia. The Southern part was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. After the I World War the Polish government postulated that this region should be included within Polish borders due to the fact that the population of Upper Silesia spoke Polish. The plan was never realized because of numerous protests put forward by German diplomacy. The years 1919 and 1920 saw two Silesian uprisings which were supported by the Polish side but which became thwarted by voluntary paramilitary groups (known as Freikorps). On the 20th of March 1921 the Upper Silesia plebiscite took place. Later that year in May, the Third Silesian Uprising broke out and, as a consequence, the League of Nations advised to divide Upper Silesia. As of 1922, the Republic of Poland received the Eastern part of Upper Silesia, along with Tarnowskie Góry (Ger. Tarnowitz), Katowice (Ger. Kattowitz) and Królewska Hutą (Ger. Königshütte, today known as Chorzów), while the German Weimar Republic incorporated its Western part with the cities of Gliwice, Bytom and Zabrze. The national minorities that remained on either side of the border were granted many exclusive rights during the Interwar Period. Their bilingualism, however, was an obstacle on determining their national identities (Eser 200: 299, 300 Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

).

).The map below depicts the formation of the Upper Silesian borders as a result of the Plebiscite of 1921.

Formation of borders in Upper Silesia in 1921. Source: [http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Granice_1921_slask_1.png]

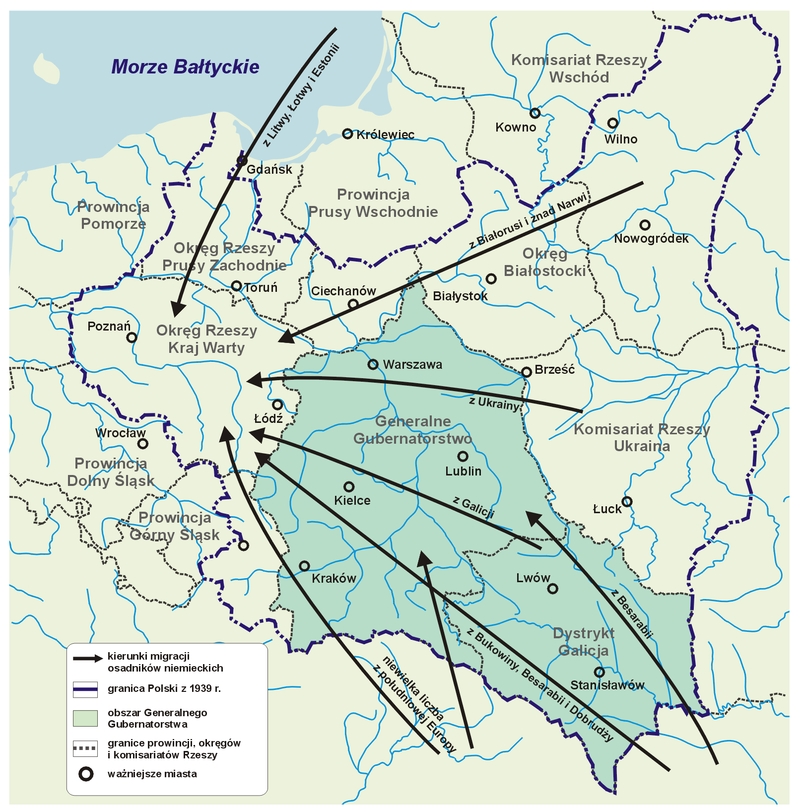

The outbreak of the II World War intensified not only the conflicts between the Polish and the German but also the contact between the two languages. In 1939 Upper Silesia was incorporated into the Reich while the Lower province was left aside military actions until 1944. Upper Silesia experienced the policies of national socialism and Germanization (cf. Eser 2000: 306, 307

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

; Kraft 2001: 208

; Kraft 2001: 208 Kraft 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kraft 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Kraft, Claudia 2001. „Dolny Śląsk. Ucieczka, wypędzenie i przymusowe wysiedlenie Niemców z województwa wrocławskiego w latach 1945 – 1950. Rok 1945.“, w: D. Boćkowski (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.IV Pomorze Gdańskie i Dolny Śląsk. Warszawa: Neriton. 204-237.

). After Poland was attacked by Hitler and Germany it became apparent that the numbers of German settlers on this territory were insufficient. That is why it was decided to resettle the populations of German national minorities from Eastern provinces (which contradicted the Drang nach Osten policy - 'Drive toward the East'). Following the formation of the Russian-Romanian borders in 1940, the Nazi government resettled the German populations of Bessarabia and North Bukovina to Reichsgau Wartheland, Pomerania and Lower Silesia. Once Nazi Germany's military dominance was broken, the German evacuees from the Reich were resettled to these areas as well (Brzezina 1989: 33, 35

). After Poland was attacked by Hitler and Germany it became apparent that the numbers of German settlers on this territory were insufficient. That is why it was decided to resettle the populations of German national minorities from Eastern provinces (which contradicted the Drang nach Osten policy - 'Drive toward the East'). Following the formation of the Russian-Romanian borders in 1940, the Nazi government resettled the German populations of Bessarabia and North Bukovina to Reichsgau Wartheland, Pomerania and Lower Silesia. Once Nazi Germany's military dominance was broken, the German evacuees from the Reich were resettled to these areas as well (Brzezina 1989: 33, 35 Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

).

).The map below depicts the directions of German settlement during the period of occupying Poland.

German settlement waves during the Nazi occupation of Poland (1939-1944) - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Brzezina 1989: 34

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brzezina 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Brzezina, Maria 1989. Polszczyzna Niemców. Warszawa, Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

By the end of the war the industrial facilities in Upper Silesia were disassembled and the ex-Nazi camps became either transition camps for those Upper Silesian natives who were to be sent to the USSR as forced labour, or internments for the German population. A decree was issued in February 1945 which excluded the, so called, "rogue elements" from the Polish society. All these who had (been) signed onto the Volksliste and were not able to rehabilitate themselves in the eyes of the government, were sent to labour camps. Members of national socialist organizations were to be arrested (Eser 200: 310-312

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

).

).It is estimated that subsequently after the war, the number of Germans living in Silesia dropped from 4.7 million (1939) to 1.5 million. The population density varied greatly in the years following the end of the war. North-Western powiats (counties) were immensely depopulated while these districts which neighboured the border established after Germany's capitulation from the South East were overflowing with West Reich evacuees, refugees from Eastern Silesia and returnees who had sought refuge in Bohemia and Moravia. Refugees from Saxony and Thuringia came back as well, as they hoped that at least a part of Lower Silesia would remain within German borders (Kraft 2001: 209

Kraft 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kraft 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Kraft, Claudia 2001. „Dolny Śląsk. Ucieczka, wypędzenie i przymusowe wysiedlenie Niemców z województwa wrocławskiego w latach 1945 – 1950. Rok 1945.“, w: D. Boćkowski (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.IV Pomorze Gdańskie i Dolny Śląsk. Warszawa: Neriton. 204-237.

).

).The first expulsions of the German population from Lower Silesia began in the summer of 1945. The initial plan was expel the German population from the thirty kilometres wide borderline belt provided for military settlement, that is, in the following counties: Żary/Sohrau, Żagań/Sagan, Zgorzelec/Görlitz, Lubań/Lauban, Lwówek Śląski/Löwenberg, Bolesławiec/Bunzlau, Jelenia Góra/Hirschberg and Ząbkowice Śląskie/Frankenstein. The borderline belt began to be cleared out on the 20th of June 1945 and it took two weeks to complete the task. It is estimated that around 150-200 thousand people left Poland at that time. Being the biggest Lower Silesian city, largely inhabited by a German population, Wrocław/Breslau was a priority target for its "purification". The transports in the first stage of the expulsion process were decided in 1946 to be directed through the British occupational zone. The first route began in Wrocław/Breslau, the second in Kłodzko/Glatz, and both of them ran through Legnica/Liegnitz. The resettlement to the Soviet occupational zone (the later German Democratic Republic) happened in July 1946. According to official data, a total of 1,298,562 people were expelled to Germany until October 1947. These organized resettlements, however, did not result in the complete "purification" of Lower Silesia from its German population. Official reports stated that 51,578 citizens of German descent still lived there in 1950. That is why throughout the 1950s the expulsions still occurred, albeit on a changed basis (Jankowiak 2001: 240-255

Jankowiak 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jankowiak 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Jankowiak Stanisław 2001. „Dolny Śląsk. Ucieczka, wypędzenie i przymusowe wysiedlenie Niemców z województwa wrocławskiego w latach 1945 – 1950. Lata 1945-1950“, w: D. Boćkowski (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t. IV Pomorze Gdańskie i Dolny Śląsk., Warszawa: Neriton. 238-261.

).

).Upper Silesia experienced resettlements early in mid June 1945. The Silesian voivode (governor) decided to undertake two such operations which encompassed Bytom and Katowice. On June the 18th 1945 it was even decreed that the region around Opole should be completely "de-Germanized". Every German sign, street name or otherwise, was to be removed. With the end of July 1945 in some villages and towns the German population was removed from their homes without any consideration or plan regarding their future fate. They were either placed in camps or rushed to the region's border and left there. Some of the expelled returned to their families in Germany. The early expulsions were performed mercilessly, resulting in many deaths. According to official statistics, from August to December 1945 a total of 90.000 people were expelled from Upper Silesia and a further 29.000 left by their own will (Eser 2000: 318-321

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

). Another attempt at expulsion took place in May 1946 as a part of Operation Swallow. Initially the operation was focused on the area around the town of Opole alone; the Eastern part of the region lacked the proper legislature to deal with Volksdeutsch issues. There the process only began in Fall 1946 following the enactment of the decree excluding those of German nationality from Polish society. As of Summer 1947, the government opted for the Polonization of the entire region as well as Polonizing German surnames. Upper Silesians were expected to take up Polish language classes (Eser 2000: 327-330

). Another attempt at expulsion took place in May 1946 as a part of Operation Swallow. Initially the operation was focused on the area around the town of Opole alone; the Eastern part of the region lacked the proper legislature to deal with Volksdeutsch issues. There the process only began in Fall 1946 following the enactment of the decree excluding those of German nationality from Polish society. As of Summer 1947, the government opted for the Polonization of the entire region as well as Polonizing German surnames. Upper Silesians were expected to take up Polish language classes (Eser 2000: 327-330 Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

). Operation Swallow resulted in the following: since the day it had started, until December 1950, a total of 21,000 people were resettled from the Silesian voivodeship. The strict and severe Polish national policies led to the separation of at least 22.000 Silesian families. Nonetheless, 80,000 Upper Silesians still admitted being German in 1952 while ID cards were being issued (Eser 2000: 331

). Operation Swallow resulted in the following: since the day it had started, until December 1950, a total of 21,000 people were resettled from the Silesian voivodeship. The strict and severe Polish national policies led to the separation of at least 22.000 Silesian families. Nonetheless, 80,000 Upper Silesians still admitted being German in 1952 while ID cards were being issued (Eser 2000: 331 Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

).

).During the communist period it was only in Lower Silesia between 1950 and 1959 that Germans could run their own schools (Witkorowicz 1997: 1956

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiktorowicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiktorowicz, Józef 1997. „Polnisch-Deutsch“, w: Goebl, Hans i in.(red.) Kontaktlinguistik. Contact linguistics. Linguistique de contact. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. 1594-1600.

). In larger towns and cities of Lower Silesia, such as Wrocław and Wałbrzych, German primary schools were opened for children of the German minority. Predominantly, these schools were small, staffed by one teacher, teaching a couple of dozen students and severely lacking proper didactic equipment. There were 132 primary and 2 secondary schools (one in Wałbrzych/Waldenburg and one in Boguszowo/Gottesberg) in the school year 1954/1955. At the start of the 1950s German-language press began to be published. Between 1951 and 1952, mining trade unions published their newspaper-mouthpiece Wir bauen auf!. Furthermore, the newspaper Arbeiterstimme, whose subtitle was Sozialistische Tageszeitung, began to be printed 5 times a week in Wrocław starting from 1952. In 1958 it transformed into the weekly 7 Tage in Polen (Kryszczuk 1999: 58

). In larger towns and cities of Lower Silesia, such as Wrocław and Wałbrzych, German primary schools were opened for children of the German minority. Predominantly, these schools were small, staffed by one teacher, teaching a couple of dozen students and severely lacking proper didactic equipment. There were 132 primary and 2 secondary schools (one in Wałbrzych/Waldenburg and one in Boguszowo/Gottesberg) in the school year 1954/1955. At the start of the 1950s German-language press began to be published. Between 1951 and 1952, mining trade unions published their newspaper-mouthpiece Wir bauen auf!. Furthermore, the newspaper Arbeiterstimme, whose subtitle was Sozialistische Tageszeitung, began to be printed 5 times a week in Wrocław starting from 1952. In 1958 it transformed into the weekly 7 Tage in Polen (Kryszczuk 1999: 58 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). A German minority population existed in the years following 1945, a population that was very well aware of their ethnic origins. Although they did not possess a permanent residence card, they were not denied their language rights in everyday life nor in schools. It was possible for them to celebrate their culture and national language by joining in the German Social-Cultural Association (Deutsche Sozial-Kulturelle Gesellschaft DSKG), which functioned legally, both with the knowledge and permission of the Polish government (Kryszczuk 1999: 61, 62

). A German minority population existed in the years following 1945, a population that was very well aware of their ethnic origins. Although they did not possess a permanent residence card, they were not denied their language rights in everyday life nor in schools. It was possible for them to celebrate their culture and national language by joining in the German Social-Cultural Association (Deutsche Sozial-Kulturelle Gesellschaft DSKG), which functioned legally, both with the knowledge and permission of the Polish government (Kryszczuk 1999: 61, 62 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). In her book (2004

). In her book (2004 Nitschke 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nitschke 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Nitschke, Bernadetta 2004. „Szkolnictwo dla mniejszości niemieckiej w Polsce w latach 1945–1989”, Rocznik Lubuski XXX/I : 103-111. [http://www.ltn.uz.zgora.pl/PDF/rocz04/9.pdf]

), Nitschke discusses the history of German minority education in Poland after the II World War.

), Nitschke discusses the history of German minority education in Poland after the II World War.It wasn't until the 1990s that the social life of the German minorities in Poland had begun to reawaken. Due to the efforts of the DSKG, a bilingual class was opened in Złotoryja in the school year 1993-1994, and in 1996-1997 a bilingual school was established (Kryszczuk 1999: 62

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). All of the German minority associations in Lower Silesia have received their headquarters thanks to the financial support of the German state. Furthermore, in Upper Silesia a number of different organizations and interest circles have been established. In the beginning of the 1990s, their total number of members amounted to around quarter of a million (Eser 2000: 331

). All of the German minority associations in Lower Silesia have received their headquarters thanks to the financial support of the German state. Furthermore, in Upper Silesia a number of different organizations and interest circles have been established. In the beginning of the 1990s, their total number of members amounted to around quarter of a million (Eser 2000: 331 Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Eser 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Eser, Ingo 2000. „Województwo śląskie. Niemcy na Górnym Śląsku“, w: W. Borodziej & H. Lemberg (red.) Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950. Wybór dokumentów t.II. Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie. Warszawa: Neriton. 290-331.

).

).

ISO Code

(Lower) Silesian German

ISO-639-3 sli

ISO-639-3 sli

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- Kauder 1937

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- Brockhaus 1997

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- przyp24

- przyp25

- przyp26

- przyp27

- przyp28

- Unwerth 1908

- Jungandreas 1928

- Menzel 1976

- Księżyk 2008

- Kryszczuk 1999

- Wiktorowicz 1997

- Bellmann 1965

- Bellmann 1967

- Bluhme 1964

- Mitzka 1953

- Veith 1971

- Kaczmarczyk 1945

- Brzezina 1989

- Eser 2000

- Morciniec 2002

- Kraft 2001

- Jankowiak 2001

- Kleczkowski 1915

- Weinhold 1853

- Kneip 1999

- Zaręba 1974

- Bogacki 2010

- Pudło 2004

- Biskup 2010

- Sprengel 1994

- Joachimsthaler 2007

- Preuss 2011

- Preuss 2009

- Mitzka 1963-1965

- Ranking dialektów

- Nitschke 2004

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Wiersz Heinricha Tchampela

- Strona tytułowa dramatu De Waber

- Śląskie dialekty języka niemieckiego

- Rozprzestrzenienie (dialektów) języka niemieckiego

- Dialekty niemieckie ok. 1910 roku

- Dialekty łużycko-śląskie na mapie Gwar niemieckich

- apis nutowy do utworu Weihnachtsglocka

- Lautdenkmal

- Oberschlesische Nachrichten

- śląskie niemieckie wykopaliska językowe

- śląskie niemieckie wykopaliska językowe

- Breslausch - dialekt wschodnio-średnio-niemiecki

- Druga kolonizacja niemiecka

- Kolonizacja fryderycjańska i józefińska

- Kształtowanie granic Polski - Górny Śląsk w 1921

- Kierunki osadnictwa niemieckiego 1939-1944

- Średniowieczna kolonizacja niemiecka

- Kartka z 40 zdaniami Wenkera

- Zapis nutowy wiersza Ärndtelied (Pieśń dożynkowa)

- Nuty do wiersza von Holteia i kartka pocztowa

- Lokalne odmiany słowa schimpfen

- Seria wydawnicza Arbeitskreis

- niemieckojęzyczna przeszłość Śląska - Rudy

- niemieckojęzyczna przeszłość Śląska - Bytom