German dialects in Silesia

Presence in public life

Media

The Schlesische Provinzialblätter was first printed in 1784 as a monthly which described current affairs in Silesia, as well as its development, its culture and language. The journal took a puristic perspective on language (for example, it protested against the usage of the French "madame") and attempted to foster a regional identity, describing the Silesian German dialect as a variety of the German language. One article even compared the Highland dialect with Swedish (Bugacki 2010: 68-71 Bogacki 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Bogacki 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Bogacki, Jarosław 2010. „Die Schlesischen Provinzialblätter als Informationsquelle über die Sprachverhältnisse im preußischen Schlesien“, w: G. Łopuszańska (red.) Sprache und Kultur als gemeinsames Erbe im Grenzgebiet. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego. 67-73.

).

These Silesian German dialects were popularized in the press mainly by

the rise of Silesian literature. Apart from publishing their owns works,

some Silesian poets would write columns in newspapers or co-publishing

them. In 1883 the Silesian poet Max Heinzel started to print his

calendar, Der Gemittliche Schläsinger. In a way, the calendar was a

yearbook for Silesian people (Menzel 1976: 105

).

These Silesian German dialects were popularized in the press mainly by

the rise of Silesian literature. Apart from publishing their owns works,

some Silesian poets would write columns in newspapers or co-publishing

them. In 1883 the Silesian poet Max Heinzel started to print his

calendar, Der Gemittliche Schläsinger. In a way, the calendar was a

yearbook for Silesian people (Menzel 1976: 105 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

). Due to the efforts of another Silesian poet, Karl Klings, the biweekly Durfmusikke

first appeared in 1912 and focused on the topic of regional art, among

others.

Presently the „Arbeitkskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart” association

strives to retain the memory of the Silesian dialects. They publish the

Rundbrief circular where Silesian poems appear in print. There are many

websites on the Internet which deal with Silesian German dialects;

nonetheless, these are often amateur endeavours which aim to support

family traditions. This website, for example, offers a test version of

Silesian German Wikipedia - http://incubator.wikimedia.org/wiki/Wp/sli/Hauptseite.

). Due to the efforts of another Silesian poet, Karl Klings, the biweekly Durfmusikke

first appeared in 1912 and focused on the topic of regional art, among

others.

Presently the „Arbeitkskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart” association

strives to retain the memory of the Silesian dialects. They publish the

Rundbrief circular where Silesian poems appear in print. There are many

websites on the Internet which deal with Silesian German dialects;

nonetheless, these are often amateur endeavours which aim to support

family traditions. This website, for example, offers a test version of

Silesian German Wikipedia - http://incubator.wikimedia.org/wiki/Wp/sli/Hauptseite.Religious life

The communities of the County of Glatz/Kladsko paid great attention to holidays in the calendar; that is why the Glatz/Kłodzko dialect was rich in saying and proverbs that related to this domain of everyday life. An example of such holidays was St. Michael's Day celebrated on the 29th of September and known as Micheele. Religious life impacted the dialect to such a degree that the church's bell would determine the period of the day, for example em ‘s Marjalätta called people to work, de lätta Mettich informed of dinner time while em’s Oomdlätta sounded the end of the working day. The relationship between godfather and godson was also important. Godfathers would be commonly addressed as Pate (godfather), e.g. Pat’ Heinrich.During the communist period in Poland, tension became visible between the Catholic German-speaking minority and the Catholic Church. The supposed non-existing German minority of Lower Silesia was denied the right to have church services performed in their native language. During his sermon on the 15th of August 1984 in Częstochowa, cardinal Józef Glemp stated that the Church could not with a clear conscience organize church services in a foreign language that people did not understand and who only wanted to learn it during the mass itself. The German press was in an uproar - how is it possible, they thought, that the Silesians, so numerously seeing themselves as Germans, can only speak some "broken" German? (Kryszczuk 1999: 61

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

).The Silesian Germans who live presently in Poland are closely tied to their heritage and origins but they are not centred around one denomination - that is why Catholicism has not denoted being Polish and Protestantism has not been tantamount to being German (Kryszczuk 1999: 95

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

).Dictionaries

In 1937, Munich, Will-Erich Peuckert published his Schlesisch dictionary. Between 1963 and 1965 a 3-volume dictionary Schlesisches Wörterbuch by Walther Mitzka appeared in print in Berlin. Mitzka's dictionary was predominantly based on the questionnaire research conducted prior to 1945: 1250 informants sent back 71 questionnaires, each of which consisted of 60 questions; in total, the author received over 27,000 questionnaires. Apart from data gathered thanks to these questionnaires, Mitzka also conducted interviews with those informants who had moved to West Germany after 1945. The work was additionally enriched by scholarly papers, historical materials as well as dialectal literary works. That is how the 3-volume dictionary, consisting of 1636 pages, 40,000 entries and 900 maps was created (Zaręba 1974: 22, 23 Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

). Another dictionary, Schlesisches Wörterbuch , was printed in 1996 in Husum thanks to Barbara Suchner who had been born in Breslau/Wrocław and for over 30 years had been writing down Silesian words, phrases and expressions. The whole dictionary consists of 8,000 entries on 238 pages; the entries are partially based on the dialects of Breslau/Wrocław, Treibnitz/Trzebnica, where her mother had been born, and, also, on the dialect of Waldenburg/Wałbrzych and Upper Silesia where her husband had come from. The dictionary lacks linguistic elaboration; according to her author, its main aim is to keep the memory of the Silesian German dialect alive, and to entertain. Alois Bartsch compiled a dictionary which focused on solely one Silesian variety - Wörterbuch Mundart der Grafschaft Glatz, that is of the Glatz/Kłodzko dialect. The Internet contains several dicitonaries of Silesian dialects. One which is dedicated to the Wrocław dialect is being created by those passionate both about the Silesian language and its culture.

). Another dictionary, Schlesisches Wörterbuch , was printed in 1996 in Husum thanks to Barbara Suchner who had been born in Breslau/Wrocław and for over 30 years had been writing down Silesian words, phrases and expressions. The whole dictionary consists of 8,000 entries on 238 pages; the entries are partially based on the dialects of Breslau/Wrocław, Treibnitz/Trzebnica, where her mother had been born, and, also, on the dialect of Waldenburg/Wałbrzych and Upper Silesia where her husband had come from. The dictionary lacks linguistic elaboration; according to her author, its main aim is to keep the memory of the Silesian German dialect alive, and to entertain. Alois Bartsch compiled a dictionary which focused on solely one Silesian variety - Wörterbuch Mundart der Grafschaft Glatz, that is of the Glatz/Kłodzko dialect. The Internet contains several dicitonaries of Silesian dialects. One which is dedicated to the Wrocław dialect is being created by those passionate both about the Silesian language and its culture.Literature

According to reliable sources (Menzel 1976: 75 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

) no other German dialect has amassed such a bulk of varied literature as the Silesian dialect has. While it holds true that Low German literature is, indeed, very rich, it cannot be compared to the sheer number of Silesian works nor the variety of forms they have taken.

) no other German dialect has amassed such a bulk of varied literature as the Silesian dialect has. While it holds true that Low German literature is, indeed, very rich, it cannot be compared to the sheer number of Silesian works nor the variety of forms they have taken.The heyday of Silesian literature occurred following the publishing of Karl von Holtei's poetry book in 1830, Schlesische Gedichte. That is not to say that nobody else had been writing in Silesian German before. The first significant work was the Biblical drama of Georga Göbel form 1586: Die fahrt Jacobs des Heiligen Patriarchens und der Ursprungk der Zwölff Geschlecht und Stämme Israel, aus dem Buch der Schöpffung Comedienweise auff Hochzeiten und sonsten zu Spielen gestelltet – von Georg Göbel, dem Kaiserlichen Notarius und deutschen Schulmeister zu Görlitz. In the II and V act of the drama, the shepherds Matz, Conte and Hentze appear speaking their Upper Lusatian dialect. The second important piece of literature is Andreas Gryphius' peasant comedy which was written in 1660. Gryphius was one of the most outstanding 17th century German poets. Die geliebte Dornrose was written in the Diphthongizing dialect spoken near Glogau/Głogów, where the poet himself lived. The plot focuses on the theme of forbidden love. A countryman, Greger Kornblume, and a countrywoman, Lisa Dornrose, are in love but their fathers hate each other. The coarse and boorish Maltz Aschewedel also has feelings for Lisa. He tries to conquer her heart with magic but as his attempts fail, he goes as far as to assault her. The drama ends with the culprit being punished; to pay for his crimes he is to help the two loved ones marry (Menzel 1976: 78, 79

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

).The aforementioned Karl Eduard von Holtei (1798-1880) from Wrocław was the most renowned Silesian poet, playwright, actor, stage director and recitor. He created dozens of poems in Silesian German. They form a type of construct created from different varieties of Silesian German. While they do not refer to one specific territory, they intertwine to compose a regional tradition covering the whole of Silesia. The most known pieces are Suste nischt, ack heem! ("Nowhere else but home!") and „Der Zutabärg” ('the Mount of Ślęża'). In the first edition of Schlesische Gedichte ("Silesian poems") both poems were published along with musical notation with the intent of playing and singing them. Another example of a well-known dialectal poem is Darheeme ("Among our own"). In 1945 the slogan Best to be at home! (the alternate translation of Suste nischt, ack heem!) expressed a natural homesickness for many native Silesians who had lost their country in the maelstrom of war; later it conveyed an ideological and political message (Pudło 2004: 28-31

Pudło 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pudło 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Pudło, Kazimierz M. (red.) 2004. Karl Eduard von Holtei (1798-1880) w pamięci dawnych i współczesnych Dolnośląskiej Ziemi Obornickiej. Oborniki Śląskie: Urząd Miejski.

). Holtei, however, is most often associated with the Wrocław dialect. This was the basis of many of his poems and, soon, became a basis for a commonly understood "shared" Silesian dialect (Menzel 1976: 84

). Holtei, however, is most often associated with the Wrocław dialect. This was the basis of many of his poems and, soon, became a basis for a commonly understood "shared" Silesian dialect (Menzel 1976: 84 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

).

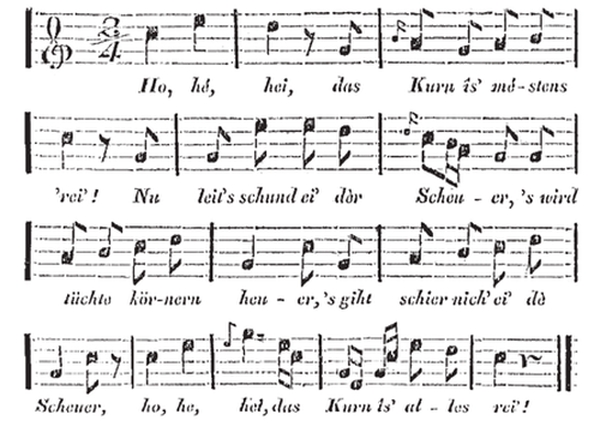

Musical notation to Ärndtelied ("Harvest Song") - Pudło 2004: 19

Pudło 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pudło 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Pudło, Kazimierz M. (red.) 2004. Karl Eduard von Holtei (1798-1880) w pamięci dawnych i współczesnych Dolnośląskiej Ziemi Obornickiej. Oborniki Śląskie: Urząd Miejski.

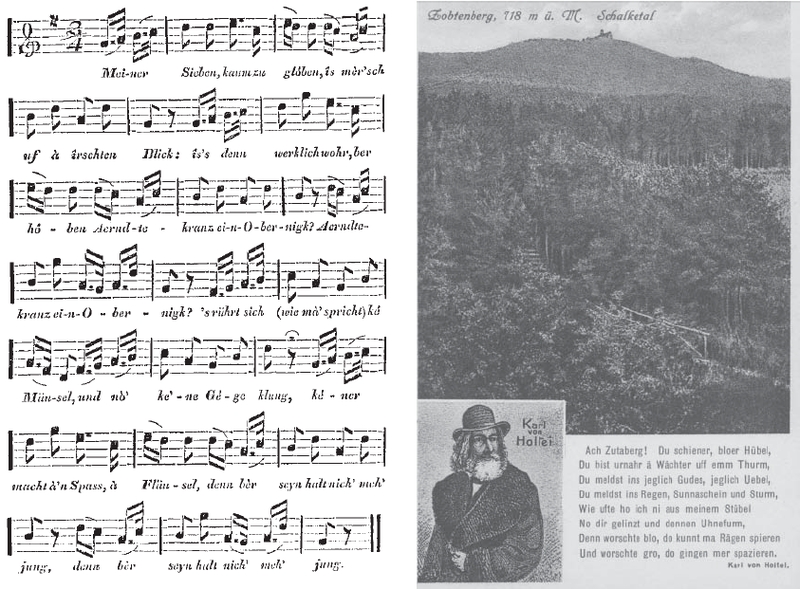

Musical notation to von Holtei's Ber seyn nich meh jung ('We're not so young anymore) and a postcard with the inscribed Der Zutabärg (‘Mount Ślęża’) - Pudło 2004: 30

Pudło 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pudło 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Pudło, Kazimierz M. (red.) 2004. Karl Eduard von Holtei (1798-1880) w pamięci dawnych i współczesnych Dolnośląskiej Ziemi Obornickiej. Oborniki Śląskie: Urząd Miejski.

.

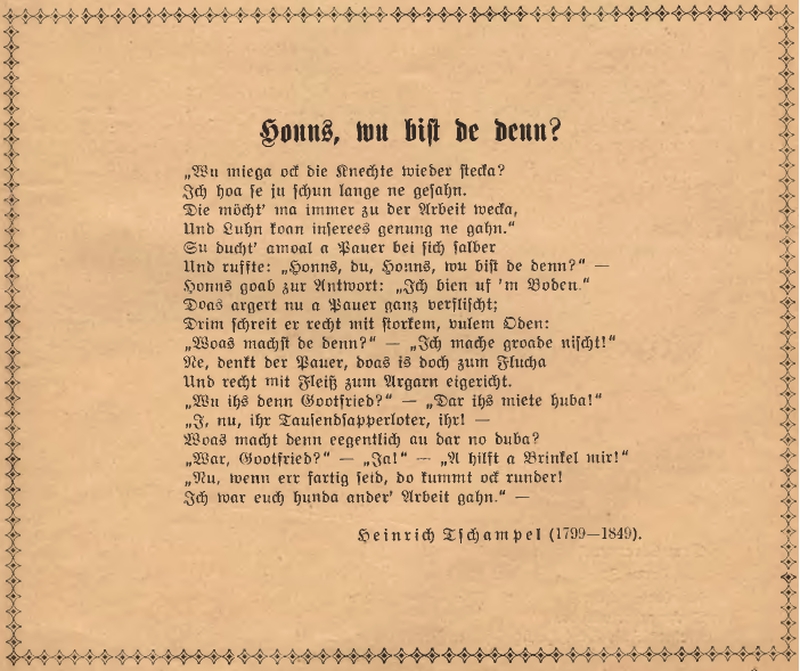

.Holtei was an example to many Silesian poets, for example Karl Heinrich Tschampel (1799-1849) who published his poetry book Gedichte in Schlesischer Mundart in 1843 and wrote his poems in the Highland dialect (Menzel 1976: 91

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

).

Heinrich Tchampel's poem Honns wu bist de denn? [Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Honns,_wu_bist_de_denn_%3F.png]

In the 1870s and 1880s, Silesian dialectal poetry experienced another heyday thanks to such poets as Robert Rößler and Max Heinzel (Menzel 1976: 97

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

). Robert Rößler (1838-1883) was brought up by a rural family. After graduating from school in Wrocław, he applied to the local university to finally achieve the degree of doctor of philosophy. Following that, he worked as a teacher in various towns. In his poems he transfers to paper his childhood memories of rural life. Der Nuußboom-Krause, Die Landerwetzka, Bibelversche and Ock immer hibsch deutsch are among the most known and favoured Silesian poems. Rößler also wrote prose. He composed humours short stories which were sometimes even based on shallow and cheap jokes. In 1877 he published the first volume of his prose work: Schnoken. This word became the name for a new genre. During the following six years, another 7 volumes appeared in print. The works of Rößler are contrasted by those of Max Heinzel (1833-1898) whose works are deemed as sophisticated and whose jokes are delicate and tactful (Menzel 1976: 102

). Robert Rößler (1838-1883) was brought up by a rural family. After graduating from school in Wrocław, he applied to the local university to finally achieve the degree of doctor of philosophy. Following that, he worked as a teacher in various towns. In his poems he transfers to paper his childhood memories of rural life. Der Nuußboom-Krause, Die Landerwetzka, Bibelversche and Ock immer hibsch deutsch are among the most known and favoured Silesian poems. Rößler also wrote prose. He composed humours short stories which were sometimes even based on shallow and cheap jokes. In 1877 he published the first volume of his prose work: Schnoken. This word became the name for a new genre. During the following six years, another 7 volumes appeared in print. The works of Rößler are contrasted by those of Max Heinzel (1833-1898) whose works are deemed as sophisticated and whose jokes are delicate and tactful (Menzel 1976: 102 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

). Initially Heinzel had qualms against writing in his own dialect but was finally persuaded by Karl von Holtei himself. In 1875 the poetry book Vägerle flieg aus was published. Heinzel's main inspirations were the love of nature, of his own small motherland and of the people that inhabited it (Menzel 1976: 103

). Initially Heinzel had qualms against writing in his own dialect but was finally persuaded by Karl von Holtei himself. In 1875 the poetry book Vägerle flieg aus was published. Heinzel's main inspirations were the love of nature, of his own small motherland and of the people that inhabited it (Menzel 1976: 103 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

). This motherland was deemed so important by him that he composed a "Silesian national anthem". He left behind a rich literary output in numerous tomes of poetry and prose. Other Silesian poets, such as Philo vom Walde, Hermann Bauch and Ernst Schenke, followed his lead (Menzel 1976: 104, 105

). This motherland was deemed so important by him that he composed a "Silesian national anthem". He left behind a rich literary output in numerous tomes of poetry and prose. Other Silesian poets, such as Philo vom Walde, Hermann Bauch and Ernst Schenke, followed his lead (Menzel 1976: 104, 105 Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

).Hermann Bauch (1856-1924) became famous in Silesia thanks to his three poems, Schläscha Sträselkucha, Juchhhanlasoft aus Silsterwitz and Die Koaschel. Following this sucess, he continued on writing and in 1886 he published a volume containing both poetry and prose: Quietschvergnügt. The theme of his works was, as in the case of many of his predecessors, rural life - which he deemed much more real than urban life. After Bauch's death his sons inherited his writings and notes. After a process of reading and selection, they later decided to publish them in a total of 3 volumes (Menzel 1976: 110, 111

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

).While Bauch would create art inspired by Rößler, another Silesian poet, Philo vom Walde (real name Johannes Reinelt, 1856-1906) was mainly influenced by Heinzel. His greatest literary achievement is Leute Not published in 1901 and written in his own dialect. He would also write poetry in Silesian German (Biskup 2010: 157, 158

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Biskup, Rafał 2010. „Philo vom Walde (Johannes Reinelt). Dialektdichter, Lebensreformer, Nietzscheanist”, w: E. Bialek i in. (red.) Silesia Nova. Vierteljahresschrift für Kultur und Geschichte 7. Jahrgang. Dresden-Wrocław.

). Vom Walde was immensely fascinated by Nietzsche's philosophy which is why a pessimistic ring to his works can be easily noticed. He was not the typical Silesian poet deeply enrooted to his own land - rather, he dreamed of far away travels and criticized provincialism. Vom Walde is known as the writer who introduced modernism into Silesian literature (Biskup 2010: 158

). Vom Walde was immensely fascinated by Nietzsche's philosophy which is why a pessimistic ring to his works can be easily noticed. He was not the typical Silesian poet deeply enrooted to his own land - rather, he dreamed of far away travels and criticized provincialism. Vom Walde is known as the writer who introduced modernism into Silesian literature (Biskup 2010: 158 Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Biskup, Rafał 2010. „Philo vom Walde (Johannes Reinelt). Dialektdichter, Lebensreformer, Nietzscheanist”, w: E. Bialek i in. (red.) Silesia Nova. Vierteljahresschrift für Kultur und Geschichte 7. Jahrgang. Dresden-Wrocław.

). In 1902 he co-published Das Schlesiche Dichterbuch along with August Friedrich Krause. It was a collection of Silesian poetry written in its dialect as well as the literary German standard. For many authors of that time it was the dialect that was the main, if not the only, aim of writing following the rise of importance of regional folk literature. The last example of his dialectal literature was Sonntagskinder. Lieder und Gedichte aus Schlesien from 1904 (Biskup 2010: 161

). In 1902 he co-published Das Schlesiche Dichterbuch along with August Friedrich Krause. It was a collection of Silesian poetry written in its dialect as well as the literary German standard. For many authors of that time it was the dialect that was the main, if not the only, aim of writing following the rise of importance of regional folk literature. The last example of his dialectal literature was Sonntagskinder. Lieder und Gedichte aus Schlesien from 1904 (Biskup 2010: 161 Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Biskup, Rafał 2010. „Philo vom Walde (Johannes Reinelt). Dialektdichter, Lebensreformer, Nietzscheanist”, w: E. Bialek i in. (red.) Silesia Nova. Vierteljahresschrift für Kultur und Geschichte 7. Jahrgang. Dresden-Wrocław.

).

).Ernst Schenke (1896-1982) can be listed as another greatly renowned Silesian writer. He was brought up in a family that spoke the dialect on a daily basis, and hence he was able to use it himself. Still young, he began writing short pieces of poetry in German but, soon, he made an attempt at composing poems in his dialect. Within a few years his works could be seen and read in local newspapers, e.g. in Der Gemittliche Schlӓsinger. During that period he also published his first small volumes of collected works: Laba und Treiba and Drinne und draußa. Schenke can be named as the most prolific Silesian poet, acclaimed by his own imaginative, melodic and elevated style of writing which focused on the simplest of things in life, simple people and nature, often bringing a measured dose of humour to his poems (Menzel 1976: 143, 145, 155

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

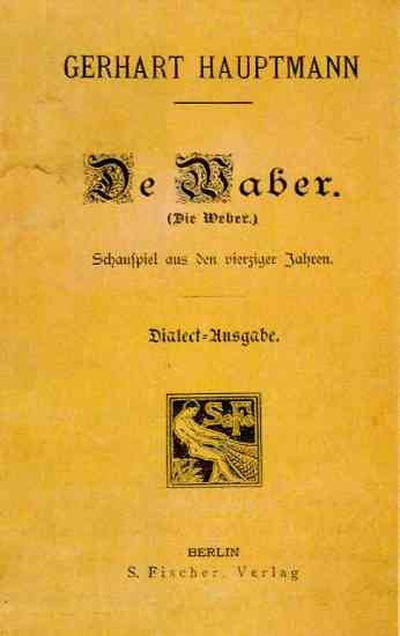

).The most crucial figure in the history of Silesian literature, however, is Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946). It is thanks to him that Silesia appeared in the canon of world literature. In 1982 he published his social drama The Weavers which was written, first, in his own dialect (De Waber), and accompanied, secondly, by a version in Standard German (Die Weber). The societal environment of Silesia, as well as its dialects, are themes that are on the foreground of the dramas Fuhrmann Henschel (1898) and Rose Bernd (1903). The first was written completely in the author's dialect. The drama series beginning with Hannels Himmelfahrt (1893) is also set in Silesia. In these works, his dialect is present in songs, sagas and fables. In the first chapter of Der neue Christophorus, the writer's poetic manifesto of kind, there are dialogues written in the dialect (Sprengel 1994: 31, 32

Sprengel 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sprengel 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Sprengel, Peter 1994. „Gerhart Hauptmann”, w: H. Steinecke (red.) Deutsche Dichter des 20. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag. 31-42.

). Weavers, wagon-drivers, farmers, foresters, blacksmiths and tavern hosts are among the Silesian figures he uses in his works. They employ a Silesian variety spoken in the region of Waldenburger Bergland (Góry Wałbrzyskie), as it is there (more specifically, from Bad Salzbrunn/Szczawno-Zdrój) that Hauptmann came from (see: Wilhelm Mentzel's on-line article). Hauptmann is considered as the most outstanding German representant of naturalism; in 1912 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

). Weavers, wagon-drivers, farmers, foresters, blacksmiths and tavern hosts are among the Silesian figures he uses in his works. They employ a Silesian variety spoken in the region of Waldenburger Bergland (Góry Wałbrzyskie), as it is there (more specifically, from Bad Salzbrunn/Szczawno-Zdrój) that Hauptmann came from (see: Wilhelm Mentzel's on-line article). Hauptmann is considered as the most outstanding German representant of naturalism; in 1912 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The front page of Gerhard Hauptmann's drama, De Waber (‘The Weavers’). Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/41/De_Waber.jpg

With the end of World War II, the Silesian Landsmannshaften (homeland associations of the exiled) in West Germany developed and fostered a literature that saw Silesia as a lost homeland, a safe and idyllic motherland (Joachimsthaler 2007: 86

Joachimsthaler 2007 / komentarz/comment/r /

Joachimsthaler 2007 / komentarz/comment/r / Joachimsthaler, Jürgen 2007. Philologie der Nachbarschaft. Erinnerungskultur, Literatur und Wissenschaft zwischen Deutschland und Polen. Würzburg: Verlag Königshausen & Neumann GmbH.

). For the next generations born in the 1960s (and born already in West Germany) Silesia was simply a place from whence their their parents came (Joachimsthaler 2007: 40

). For the next generations born in the 1960s (and born already in West Germany) Silesia was simply a place from whence their their parents came (Joachimsthaler 2007: 40 Joachimsthaler 2007 / komentarz/comment/r /

Joachimsthaler 2007 / komentarz/comment/r / Joachimsthaler, Jürgen 2007. Philologie der Nachbarschaft. Erinnerungskultur, Literatur und Wissenschaft zwischen Deutschland und Polen. Würzburg: Verlag Königshausen & Neumann GmbH.

).

).Status

The Silesian German dialect was in common usage among the lower classes of society. It was spoken in the home, whereas schools required the Standard German language. Not uncommonly, parents would prohibit their children from using the Silesian dialect at home. It was a widespread belief that only farmers and peasants spoke this way (cf. Kryszczuk 1999: 96 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

). The flourishing of Silesian dialectal literature, instigated by the publishing of Karl von Holtei's Schlesische Gedichte poetry book in 1830, brought some degree of popularity to the dialects themselves. Thanks to this event, the "dialect" became elevated to "language of poetry".

). The flourishing of Silesian dialectal literature, instigated by the publishing of Karl von Holtei's Schlesische Gedichte poetry book in 1830, brought some degree of popularity to the dialects themselves. Thanks to this event, the "dialect" became elevated to "language of poetry".The Silesian poet Philo vom Walde commented on the increasing popularity of dialect-written poetry the following way: "It must stem from the shallowest degrees of naivety to believe that dialectal poetry is worse of an art and that a dialectal poet is worse of a poet. To describe kings or to describe farmers is fundamentally the same thing: Men are men and art is art” (Biskup 2010: 163

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Biskup, Rafał 2010. „Philo vom Walde (Johannes Reinelt). Dialektdichter, Lebensreformer, Nietzscheanist”, w: E. Bialek i in. (red.) Silesia Nova. Vierteljahresschrift für Kultur und Geschichte 7. Jahrgang. Dresden-Wrocław.

). In the 1902-published calendar Der gemittliche Schläsinger, vom Walde postulated to establish an association which would foster the Silesian dialect and Silesian poetry (Verein zur Pflege schlesischer Mundart und Dichtung). The association's main aim was to fight with the conviction that Silesian is "more raw, uglier and to a lesser degree poetic than plattdeutsch ". The writers also called for the provision f Silesian poetry with some subtlety and gentleness, as it was the case with Bavarian literature. He believed that "too much attention is paid to the faithful recreation of dialect and humour". He pose the question "why shouldn't we use the Silesian dialect for artistic purposes?". Vom Walde was troubled that "the educated see Silesian dialects as ‘a broken German standard’, a common patois which has no admittance to art" (Biskup 2010: 163, 164

). In the 1902-published calendar Der gemittliche Schläsinger, vom Walde postulated to establish an association which would foster the Silesian dialect and Silesian poetry (Verein zur Pflege schlesischer Mundart und Dichtung). The association's main aim was to fight with the conviction that Silesian is "more raw, uglier and to a lesser degree poetic than plattdeutsch ". The writers also called for the provision f Silesian poetry with some subtlety and gentleness, as it was the case with Bavarian literature. He believed that "too much attention is paid to the faithful recreation of dialect and humour". He pose the question "why shouldn't we use the Silesian dialect for artistic purposes?". Vom Walde was troubled that "the educated see Silesian dialects as ‘a broken German standard’, a common patois which has no admittance to art" (Biskup 2010: 163, 164 Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biskup 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Biskup, Rafał 2010. „Philo vom Walde (Johannes Reinelt). Dialektdichter, Lebensreformer, Nietzscheanist”, w: E. Bialek i in. (red.) Silesia Nova. Vierteljahresschrift für Kultur und Geschichte 7. Jahrgang. Dresden-Wrocław.

).

).Gerhart Hauptmann, the writer who brought Silesia to the canon of world literature, commented upon how he wrote his drama using his own dialect: "I was able to write The Weavers (...) because I know the dialect. It was my full intention to introduce it into literature. I did not think of art or regional poetry (Heimatkunst) which treats dialects as a curiosity, a thing to be treated with a pinch of salt. For me, the dialect has been a gift from nature and art, a gift equal to literary German, a device thanks to which this great drama (...) has acquired its full shape. I wanted to bring the dialect its dignity back. It is for you to decide whether I was successful" (Menzel 1976: 74

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

).

).Not only Silesian poets appreciated their own dialects. Frederick the Great himself is said to have liked the pronunciation of the suffix -en as -a in the Highland dialect. Supposedly he even considered substituting a for "that bland e" in the literary German standard (Weinhold 1853: 19, 20

Weinhold 1853 / komentarz/comment/r /

Weinhold 1853 / komentarz/comment/r / Weinhold, Karl 1853. Ueber deutsche Dialectforschung. Die Laut- und Wortbildung und die Formen der schlesichen Mundart mit Rücksicht auf verwantes in deutschen Dialecten. Wien: Verlag von Carl Gerold u. Sohn.

).

).Research on the linguistic competence of Germans living in lower Silesia conducted by the end of the 20th century showed that although the majority of Lower Silesian Germans do not speak Silesian dialects due to the disintegration of their traditional communities, they do appreciate the dialect and for many it is a means for external expression. Many people attend plays and drama which are written in Silesian German dialect. The dialect, thus, alongside the German language itself, is employed as a factor responsible for creating their ethnic identity. (Kryszczuk 1999: 154

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

).Examples

Examples of literature

1. Andreas GryphiusDie geliebte Dornrose (fragment)

WILHELM VON HOHEN SINNEN: Man hat an euch nichts zu erhalten. Drumb immer fort! Jedoch, wo ihr hirmit versprechet euch zu bessern.(Menzel 1976: 79, 80

FRAW SALOME und MATZ ACHENWENDEL: O ja, ja, ja, ja, ja, o ja!

WILHELM VON HOHEN SINNEN: So soll euch hirmit das Leben geschencket seyn mit dieser ausdrücklichen Bedingung, dass ihr euch morgen zusammen treuen lasset.

GREGER KORNBLUME: Selde sich doch inner liber sechs mohl hengen lussen, asse dan alden groiliche Beer namen.

MATZ ASCHEWEDEL: Ja, du hast gut sayn, ‘s Laben is lib.

WILHELM VON HOHEN SINNEN: Stracks gebet einander die Hände und bessert euch. Wo nicht: So wird das letzte ärger werden, als das erste.

JOKEL DREYECK: O wie wor mir vor a su bange!

BARTEL KLOTZMANN: O wie enge wor mir dar Peltz!

GREGER KORNBLUME: Das seen Wunder der Liebe!

LISE DORNROSE: Also wird treue Keuschheit gekrönet!

MATZ ASCHEWEDEL: Och, wie schwingelte merr für der Litter!

FRAW SALOME: Au, wie krümmerte mich der Rücken! Nu war achts? Noch bekumme ich an hübschen jungen Monn dervon.

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)2. Karl Gustaw von Holtei

Heem will ihch

Mihch han se ooch schund manchmal da und durten(Source: http://gedichte.xbib.de/Holtei_gedicht_Heem+will+ihch.htm )

gar sihr traktiert und han mer Gutt‘s getan,

bei Fürschten und Herzogen und bei Grawen,

scheene Frauvölker und gelehrte Herrn,

in grußen Städten und uf hochen Schlössern,

in fremden Landen aber suste wu, dass ihch eegen schaamzen, weil

ihch‘s ihm nich wert bihn! – Nu‘s gefiel mir schund, o ja! –

Im besten Freu‘n, im allergrüßten Teebse,

liß sihch doch immerzu de Sehnsucht spieren.

Nach wahs? – Nu globt mersch, ader globt mersch nich:

nach meinem kleenen Haus in Obernigk samt seinem Schindeldächel

und a Tannen,

die vur der Türe stihn, däm bissel Gaarten,

däm Taubenschlage und där grünen Laube!

Wie schilgemol, - du weeßt‘s mei lieber Gott –

hab ihch geseufzt und seufz‘ ich hinte noch:

Heem will ihch, suste weiter nischt, ock heem!

The Schlesiche Gedichte poetry collection is available at: http://books.google.de/books?id=FTdKAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=de#v=onepage&q&f=false

3. Karl Heinrich Tschampel

Do derschrickt ma(Menzel 1976: 92

Uff’s Feld zum Voater, dar de Gaarschte recht,

Kimmt raus sei jüngster Suhn eim fliksta Sprunge,

Just, wie a ufgescheechtes Reh gejächt;

Und schunt vo weitem schreit dar kleene Junge:

„Och Voater, Voater, kummt ock bahle rei!

Doch macht su flink er kinnt, kummt itze glei!“

„Woas hoots denn oaber?“ – Nu de Mutter, och!

Die ihs su krank und koan ne sahn und hieren.“ –

„Och Jetersch, Junge, ne du hust mich doch

Derschrackt, doß mich der Schlag fost kunde rühren;

Denn wie de schreest su laut, - ‘s ihs ungeloin –

Ducht ihch schun, ‘s Kathla wär‘ dervo gefloin.“

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)Gedichte in schlesischer Gebirgsmundart: nebst einem Anhange, enthaltend einige Gedichte in gewöhnlicher Schriftschprache, i.e. the poetry collection written in the Highland dialect is available at:

http://books.google.de/books?id=0pgMAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=pl#v=onepage&q&f=false

4. Robert Rößler

Der Nussboom-Krause (fragment)(Menzel 1976: 98, 99

Ei insem Durfe im letzten Hause,

Do wohnt‘ a Moan und där hieß Krause;

Asu genennt in Kleen und Gruß,

Ollengen hieß a „der Krause“ bluß.

Bei Vürnähm woar a, wie bei Geringe,

Halt „der Herr Krause“. Gutt dam Dinge!

Bestand hoat oder nischt uf Erden;

Dahie sullt’s ooch noch andersch werden.

Denn’s Schicksal salber mengte sich nei:

‘s zug noch ee Krause eis Dörfel rei.

Nu hieß natierlich jeder vo beeden

„Herr Krause“. Wie sullt ma se underscheeden?

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)5. Max Heinzel

Ei der Durfschenke (fragment)

BAUER: Sie sein wulln ni vu hie – gelt?(Menzel (1976: 105, 106

FREMDER: Nein, lieber Mann!

BAUER: Sahn Se, doas ducht‘ ich – nu apriko! – do sein Se verleichte der neue Präsedente vum Gerichte – hä?

FREMEDER: Nein, lieber Mann!

BAUER: Sahn Se, doas ducht‘ ich – adder hoan Se verleichte die Zündhölzelfabrike ei Schwammelwitz?

FREMDER: I, Gott bewahre!

BAUER: Sahn Se, doas ducht‘ ich! – Nu, do wer’n Se wull vum Signare sein?

FREMDER: Ich singe nicht.

BAUER: Sahn Se, doas ducht‘ ich! – Do sein Se wull ärnt a Stoadtroath, adder su woas? He?

FREMDER: Unausstehlicher Mensch! Scharfrichter bin ich – ich thue morgen einen ab in der Stadt.

BAUER: Sahn Se, doas ducht‘ ich!

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)Der Perpendickel(Menzel 1976: 106

A Segermacher ei am Städtel –

Itz is a tudt, und a vergleicht sich

Zu anner stiehn geblieb’nen Uhre,

Die ei der Ewigkeit vu neuem

Ei Gang gebrucht und ufgezoin wird –

Wie der amoal su arbt ein Stübel,

Do kimmt a Mutterle vum Durfe

Und brengt a’n Perpendickel, brengt se,

A sol da Dingrich repperieren.

Der Meester Völkel scheubt de Prille,

De gruße Prille uf die Sterne

Und sitt su fluschelnd uf de Ale

Und spricht: „Ja, Mutter, hiert ock, hoatt’r

A Seger ni miet reigebrucht?“ „A Seger?“

Frät ünse Mutterle und külstert,

„Der Seger, Meester Völkel, gieht schun,

Ock der verdammte Perpendickel,

Der faule Nickel, tutt ni giehn!“

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)6. Hermann Bauch

Gruss-Brassel (fragment)

De Schläsing ihs a prächtig Land,(Menzel 1976: 112

Is schinnste wull eim Reiche.

Vo ollen Ländern weit zengstrim

Kimmt kees der Schläsing gleiche.

Und mitten drin oam Uderstrand

De Krone ligt vom Schlesierland:

Doas ale, gude Brassel!

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)7. Philo vom Walde

Wiegenliedel (fragment)

Nin, nin, nei –(Menzel 1976: 115

Kindele, schlof ei.

Schlof ock, draußen gieht der Wind,

Bist ju doch mei guldnes Kind.

Hul, lul, lei.

Nin, nin, nei –

Kindele schlof ei.

Schlof, du kleener Strampelgeist,

Daß dich nich is Hundel beißt,

Hul, lul, lei.

Nin, nin, nei –

Kindele, schlof ei.

Schlof, sust kimmt der schwarze Man.

Där wil’s Kindel mite han.

Hul, lul, lei.

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)8. Ernst Schenke

Hohelied der Heimat

Wie schien läßt sichs derrheeme(Menzel 1976: 147

Eim weecha Groase ruhn;

Wie nicka zengs die Beeme:

Ruh aus, mei Suhn…

Und Kinder hoots und Kalbla

Und Schäfla, schworz und groo.

Und Sperliche und Schwalbla

Und Blümla oo…

Ich hoa ei fremda Ländern

Mich reichlich imgesahn,

‘s ies merr, ich koans nich ändern,

Nischt droan gelan.

Woas die durt draußa macha,

Macht mich dohie nich fruh.

Hurch, wie die Schwalbla lacha,

Die wissa’s ju.

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Menzel 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Menzel, Wilhelm 1976. Mundart und Munadrtdichtung in Schlesien”, 2. Auflage, München: Delp’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

)

)9. Gustav Buchenthal

Wiesenblumen: Gedichte humoristischen Inhalts in schlesischem Land-Dialekt - available at:

[http://books.google.pl/books?id=tW86AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA14&dq=Reichsteen+ei&hl=de&sa=X&ei=CeUJT8nBJYztsgbvwLGBDw&sqi=2&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Reichsteen%20ei&f=false]

10. Friedrich Zeh

Gedichte in schlesicher Gebirgs-Mundart mit 22 Abbildungen – available at: [http://www.bsb-muenchen-digital.de/~web/web1012/bsb10123872/images/index.html?l=de&digID=bsb10123872&v=100&nav=0]

11. The Glatz dialect and its authors

The webpage http://www.grafschaft-glatz.de/archiv/mundart1.htm offers poetry written in the Glatz dialect. Once a month the most interesting poem is chosen and granted the title of "poem of the month".

The poem of September 2009:

Max Volkmer

Der Spritzamääster

Mich hoan se fier a Feuerschutz

Eim Darfe eigesotzt

Schon viele Joahre. Jedes wäß’s:

Dorch mich ward nischt verpotzt . . .

Ich bien gewessahoft goar sähr

On mach‘ mei Sache gutt;

Doß oalls ei bester Ordnung bleit,

Doo bien ich of der Hutt.

Ich sah zum Rechta ieweroal

Eim Spritzahause - gell! -

Denn, wenn‘s amool a Feuer hoot,

Doo gieht‘s goar roasnich schnell . . .

Doo muuß ma baale flink zer Hand

Sei ganzes Läschzeug hoan

On äne Monnschoft, stroamm geschult,

Die ma gebraucha koan . . .

Joo, wenn oalls kloppt, ich koan‘s euch sään,

Tutt‘s Feuer glei vergiehn,

On jedes koan beruhicht dann

Of häämzu wieder ziehn.

Nie woahr, ihr gatt mer oalle recht,

Doas wääß ich ganz gewieß: -

Es ies schon gutt, wenn of‘m Domm

Der Spritzamääster ies . . .

Poems in the Glatz dialect written by the readers can be found by clicking the link below: http://www.grafschaft-glatz.de/archiv/mundart2.htm

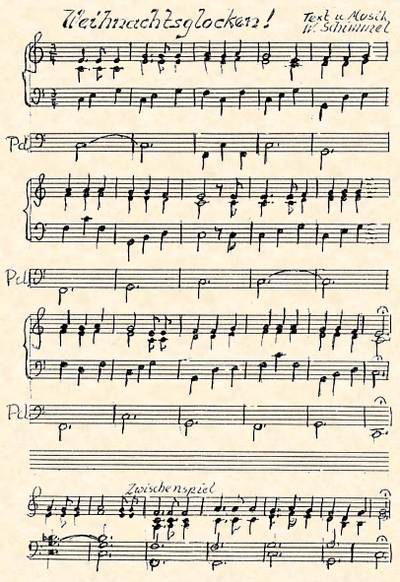

An example poem along with its Standard German version, written and translated by Willan Schimmel:

| Standard German | Glatz dialect |

| Weihnachtsglocken | Weihnachtsglocka |

| Herzenszeit - Weihnachtszeit, Jesus ist kommen zu uns auf Erden, kehrt ganz bei uns ein. Wir singen und spielen: Ein Ros‘ ist entsprungen, die Glocken, sie klingen so hell und so rein. Die Glocken erklingen mit himmlischem Schalle, das Jesuskind wird uns von Gott hergesandt, Herr Jesus geboren für Menschen uns alle, gekommen aus Gottes hochheiligem Land. Als Retter kamst Jesus, geboren zu lehren, zu retten die Menschheit von Sünden so groß, im Namen des Vaters, wir danken, dich ehren, unser Leben liegt in Dein‘ und des Vaters Schoß. | ‚s ist Weihnachta, Herzenszeit, Jesus is komma zu ons of die Arde, kehrt ganz bei ons ei! Mir senga on spiela: Ein Ros‘ is entspronga. Die Glocka, die klenga asu fein on ganz rein. Die Glocka, die hört ma mem himmlischa Schalle, dos Jesuskend wurd‘ ons vom Herrgott gesandt. On Jesus geboorn fer Menscha ons olle Gekomma aus ‚m göttlicha Heimatland. Ols Retter koomst Jesus, geboom ons belehm on retta ons Menscha vo a Senda asu gruuss. Em Noma vom Voter, mir danka, dich ehr‘n Onser Laaba is ei demm on des Voters Schoos. |

A collection of anecdotes in the Upper Silesian dialect, P. Wendelin’s humoristische Pilln kägn ollerhand Mucken und Grilln: [http://books.google.pl/books?id=hpMMAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=

de&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false]\

Proverbs, saying, folklore, other samples:

♦ A number of example sentences and words in the Highland dialect:

| Standard German | Highland dialect | English |

| „Essen, trinken, schlafen” | „Asse, trinke, schloofa” | "Eat, drink and sleep" - reputedly the most important words in this dialect. |

| Er kommt gleich. | Er kimmt glei. | He will come in a minute. |

| Ich habe ihn gesehen. | Ich hoa a gesahn. | I saw him. |

| (…) gehen in die Mühle | (…) giehn ei da Miehle. | (we're) going to the mill. |

| Er hat einen schönen Hut | A hoot an schinn Hutt. | He's got a nice hat. |

| Es ist schon gut! | ‘s ies schunt gutt! | Now it's okay! |

| Grüß nur schön zu Hause! | Griß ock schien derrheeme! | Just say Hi! from me to everyone in the house! |

| Wir essen gerne ein Stück gute Torte im Garten. | Mir asse ganne e Stickla gutte Totte eim Gattn. | We'd love to eat a piece of good cake in the garden. |

| Alte Nägel halten nicht, neue Nägel halten auch nicht! | Ala Nala haie nä, noia Nala haie a nä! | The old screws don't hold, but the new screws don't hold either! |

| Künstler tritt auf die Bühne. | Kinstler tritt uff de Biehne. | The artist appears on stage. |

| Wanduhr mit den Gewichten | Seeger | wall-clock |

| Zehnpfenniger | Biehma | a 10-pfennig coin |

| Fünfpfennigstück | Sechser | a 5-pfennig coin |

| Brotschrank | Ollmer | breadbin |

| etwas langsam tun, eigentlich lange erzählen | mahrn | to do something slowly, to take a long time telling something |

| gern | ganne | gladly |

| morgen | munne | tomorrow |

Source: the chapter Wie geht nun Schlesisch? Wie spricht der Schlesier? on the the webpage: http://home.arcor.de/jean_luc/Deutsch/mundart/schlesien.htm

♦ Example sentences in the Glatz dialect:

| Standard German | Highland dialect | English |

| Mädchen und Jungen | Mädla (Maidla) on Jonga | girls and boys |

| (…) trinke gerne eine Neige Milch | (...) trinka ganna a Näjla Melch | (I'll) eagerly drink the rest of the milk. |

| Zu Pfingsten sind die Mädchen am schönsten! | Zu Pfingsta sein die Madlan om schinnsta! | The girls are at their best during the Green Week! |

Source: the chapter Wie geht nun Schlesisch? Wie spricht der Schlesier? on the webpage http://home.arcor.de/jean_luc/Deutsch/mundart/schlesien.htm

♦ A comparison of words in the Northern and Southern Glatz dialects, and Standard German:

| Standard German | Northern Glatz dialect | Southern Glatz dialect | English |

| Heimat | Häämte | Haimte (a-i) | little homeland |

| kleines | kläänes | klaines | small |

| Häuschen | Häusla | Hoisla | a little house |

| kleiner Wagen | kläänes Wäänla | klaines Woinla | a small car |

| Steine | Stääne | Staine | stones |

| er hat gesagt | a hoot gesäät | a hoot gesoit | he said |

| allein | allääne | alleine | lonely |

| am Wege | om Wääche (Wääje) | om Waiche (Waija) | on the road |

Source: the chapter Die Mundart der Grafschaft Glatz on the webpage: http://www.grafschaft-glatz.de/mundart.htm

♦ A comparison between the Glatz dialect and the Highland dialect (although the Glatz dialect developed from the Highland dialect they differ considerably in their lexicon):

| Highland dialect | Glatz dialect |

| Duu

kannst gleeba; iech hoa diech nie (nich) beleun. Meine Schwaster, die

hotte Taag un(d) Nacht keene Ruhe. Die hotte an(‘n) ganze Neeje (Neege)

Kinder derheeme, is sein ou (oo) zwee hibische Maadla derbein. | Duu

konnst mersch gloin, iech hoa diech nie beloin. Mei Schwaster, die

hott’ Toag - on kai Ruhe. Die hott a ganze Naije Kender derhaime, ‘ s senn aa zwee (zwun) hische Maidla derbeine. |

♦ Here you can find an example of a nursery rhyme of Heinz Olesch in which words form the Upper Silesian dialect appear (marked in bold font) and are explained in Standard German:

Ein Wort gibt das andere – und die HeimatThe complete version is available at : http://www.gk-1997.de/Oberschlesisches.htm#2

Kohlrabi ist ‚ne Oberrübe,

wer Dresche kriegt, der bekommt Hiebe.

Welschkraut ist Wirsing, wie man weiß,

wer kaschelt, der rutscht übers Eis.

Haderlok ist ein Lumpensammler,

ein Hachor ist ein halber Gammler.

Mit Gutalin putzt man die Schuhe,

die Potschen bring‘n den Füßen Ruhe.

Babe ist Kuchen, Brinkel sind Krümel,

ein Pamprin ist ein richt‘ger Lümmel.

Wer schlafen will, braucht ‚ne Zudecke,

ein Reißbrettstift heißt bei uns Zwecke.

It can be observed that the Upper Silesian dialect has been influenced by a many borrowing from Polish, which is evidenced by the following words, e.g. Hopek:

| Standard German | Upper Silesian dialect | English |

| kleiner Mensch | Hopek, Hoppek | a small human, a short man |

| Irre | Ipta | idiot, fool |

| Hosentasche | Kabsa | trouser pocket |

| Lärm | Larmo | noise |

| Mutter | Muttel | mum |

| Appetit auf etwas | Zipek | an apetite for something |

| Bettwäsche | Ziche | linen |

The above examples come from a dictionary compiled by amateurs wanting to save the Upper Silesian dialect as a part of German cultural heritage. The author calls Upper Silesians to propose new entries and suggestions. The dictionary can be found on: http://www.kmosler.de/Sprache/Woerterlisten/OS-Woerter.html.

This is an example of a joke where Antek and Josek, two figures existing in the local type of humour, speak in the Upper Silesian dialect (marked in bold):

Antek und Josek bummeln in philosophischem Schweigen am Klodnitzkanal entlang, so auf Laband zu. Auf einmal bleibt Antek stehen, guckt sich den Josek durchdringend an und sagt:Source: the chapter Oberschlesien on the webpage: http://home.arcor.de/jean_luc/Deutsch/mundart/schlesien.htm

“Weißt du, Josak, da macht ich ja schont lange wissen, warum den Fische und kenn ieberhaupt nich sprechen.“ Josek überlegt eine Weile und fragt dann verwundert: „Waas, das wundert dich?“

“Jäsder, ja, das wundert mich.“

“Du Duppa“ ‚ sagt Josek, „da brauchs dich je kein bissel wundern! Sprich du doch mal, wenn du und du hast dem Frässe unten im Wasser!

♦ A poem written in the Diphthongizing dialect along with equivalent version in Standard German:

| Standard German | Diphthongizing dialect |

Gehst du mit über die Oder? Drüben ist Musik, sieben Stückel einen Böhm, das geht einmal schön! Du was hat‘s denn dort? Mohn! Und dort? Auch Mohn! Nu da, lauter Mohn, Mohn! | Geihste meite eiber da Auder? Dreibm is Mausikk, Seibm Steikl an Beihm, Doas geiht amo schein!“ Dau-was haut‘s‘n dau? Mau! Und dau? Au Mau! Nu dau, dau, lauter Mau Mau! |

Source: Neiderländisch available at the webpage http://home.arcor.de/jean_luc/Deutsch/mundart/schlesien.htm

♦ A number of words in the Breslau/Wrocław dialect:

| Standard German | Breslau dialect | English |

| Ohren | Löffel | ears |

| Geld (Münzen – monety) | Mücken | money |

| Mutter | Mutta, Muttel | mum |

| - | Usinger | a person from Silesia (humoristic) |

| ein bisschen | a wing | a bit |

| Messer | Närre | knife |

| Kopf | Nischel | head |

| reden/sprechen | räden | to talk, to say |

| Hund | Töhle | dog |

The examples come from the Online Dictionary of the Breslau Dialect which has been compiled by a hobbyist; the complete version is available at: http://www.breslau-wroclaw.de/de/breslau/history/sprache/?start=A

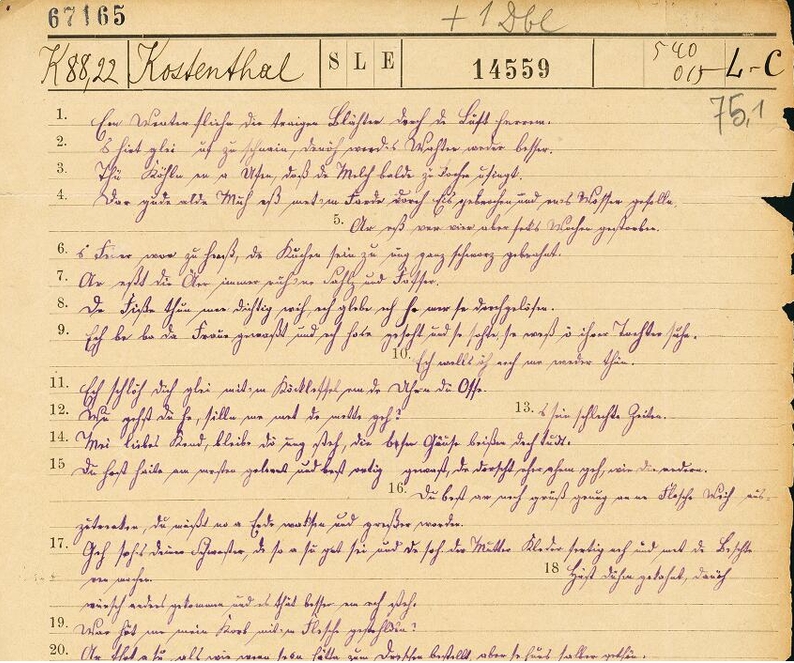

♦ A sample of the dialect spoken in the German language enclave around Gościęcin (Kostenthal):

| Standard German | Kostenthal dialect | English |

| Heirate oder heirate ich nicht? | Heirote ech oder heirote ech nech? | Will I get married or will I not? |

| Karl

war ein Mal ein bisschen zu lange im Kretscham gewesen. Er hatte

Spieler getroffen und da konnten sie nicht voneinander gehen. Da ging er

spät nach Hause und am anderen Tag ging es früh gar nicht aus dem Bett

raus. Die Sonne schien schon sehr hell, aber er stand noch nicht auf,

sie wurde immer heißer, sie brannte schon aufs Gesicht… | Kolle

woor ämöl a besken zü lange em Kratschen gewast. Ä hotte Speeler

getroffn ond do kunntn se nech vu nander geh’. Dö ging ä spät äheem ond

da ander Tag frieh ging’s gornech aus ‘em Bette raus. De Sonne schaante

schon siehr helle, aber ä stand no nech uff, se worde immer heeßer, se

brannte schont uffs Gesechte… | Once upon a time Karl took too much time being in the tavern where he met some players and could not part. Late did he return home, and the following day he did not wake up early in the morning. And the sun glared with such strength, hotter and hotter, scorching one's face... |

State of knowledge

Recordings

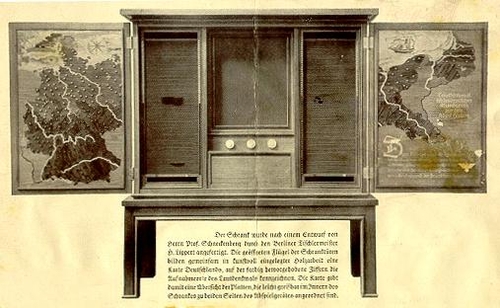

Samples of Lower and Upper Silesian dialects (among others, dialect from Glogau/Głogów, Trebnitz/Trzebnica, Brieg/Brzeg) can be found in the Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher Mundarten, a collection of recordings of German dialects which was created between 1936-1937 and was gifted to Adolf Hitler for his 48th birthday. The Deutscher Sprachatlas Research Centre in Marburg currently is in the possession of these materials. There are also two recordings of Lower Silesian German dialects which can be found on the webpage of one of the staff members of Deutscher Sprachatlas, Dr. Wolfgang Näser [http://staff-www.uni-marburg.de/~naeser/dial-aud.htm]; the first was recorded in the vicinity of Waldenburg/Wałbrzych, while the other in the region of Neumarkt/Środa Śląska. They were made between 1955 and 1957 as part of a dialectological research on East German language varieties. According to the raport of 1977, over 370 samples were recorded.

Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher Mundarten – a gift for Adolf Hitler; A cabinet containing the necessary equipment and discs containing recordings of German dialects [source: http://www.uni-marburg.de/~naeser/ld00.htm]

Radio Berlin Brandenburg's webpage

Ranking dialektów / komentarz/comment/r /

Ranking dialektów / komentarz/comment/r / Dostęp 12.01.2014 [http://programm.ard.de/TV/rbbfernsehen/die-30-beliebtesten-dialekte/eid_282055845177873]

in their article present a ranking of the 30 favourite German dialects. The Silesian dialect, accompanied by its recording, took 27th place while the Berlin dialect came first. There was, however, no mention of the way the vote had been conducted, who had voted nor what had been the criteria.

in their article present a ranking of the 30 favourite German dialects. The Silesian dialect, accompanied by its recording, took 27th place while the Berlin dialect came first. There was, however, no mention of the way the vote had been conducted, who had voted nor what had been the criteria.Archives, maps, atlases

The first work relating to the geography of Silesia was the research of Bartłomiej Sthen from 1512 in which he described the course of the Polish-German border along the Eastern Neisse (Neiße/Nysa Kłodzka) and Oder/Odra rivers. The data presented, however, may be inaccurate as unpublished church statistics and population censuses from the beginning of the 19th century lead to believe that both the Polish people and language at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries were much more widespread to the West than then contends n his data for the 16th century (cf. Zaręba 1974: 18 Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

).

).Research on linguistic geographies of German is bound by the name of George Wenker. In 1876 he began to send questionnaires to teachers from different localities to comprehensively research various aspects of dialectology. Following initial research into Rhinelandic dialects he extended his work to cover the whole territory of the German state. His questionnaire encompassing, at first, 38 sentences was added with another two, totalling the word count at 355 words. Written in the literary German standard, the questionnaire was meant to gather corresponding sentences written in the local dialects for the purpose of later phonological, syntactical and inflectional analyses (Zaręba 1974: 12

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

). The questionnaires were sent every single school in Germany and between 1879 and 1887 over 40,000 answers from over 40,000 municipalities. Wenker managed to analyse only a small portion of the materials and in 1881 he published the first volume of his Linguistic Atlas of Northern and Mid Germany. To summarize, Wenker drew by himself 1606 maps which he passed on to Marburg's Sprachatlas work group. Marburg has been known as the centre of German dialectology since 1887. This collection became the basis for other linguistic atlases (Zaręba 1974: 13

). The questionnaires were sent every single school in Germany and between 1879 and 1887 over 40,000 answers from over 40,000 municipalities. Wenker managed to analyse only a small portion of the materials and in 1881 he published the first volume of his Linguistic Atlas of Northern and Mid Germany. To summarize, Wenker drew by himself 1606 maps which he passed on to Marburg's Sprachatlas work group. Marburg has been known as the centre of German dialectology since 1887. This collection became the basis for other linguistic atlases (Zaręba 1974: 13 Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

).

).Marburg's Deutscher Sprachatlas project collects data on German language varieties. The project's website provided scans of Wenker's original questionnaires for various localities, Silesian ones included. The whole atlas is available in digital format [http://www.diwa.info], similarly as its browser of towns and their corresponding questionnaries [http://www.regionalsprache.de/Wenkerbogen/Katalog.aspx]. An example of such a questionnaire for the town of Gościęcin can be found below.

A page with Wenker's 40 sentences from Gościęcin/Kosthental. Source: http://www.regionalsprache.de/Wenkerbogen/WenkerbogenViewer.aspx?Id=40573.

After Wenker's death in 1911 his long-standing co-worker, Ferdinand Wrede, continued his work on the atlas. He extended the research by sending the questionnaires to Polish-speaking territories which had been annexed by Germany. That is how the research was able to cover, for example, 376 Polish towns which belonged to Prussia (until 1918) and Germany (after 1918 for those Polish areas which remained within German borders). In 1956 Walther Mitzka finalized the research which had been on-going for the past decades. A total of 11 volumes were published; Volumes 1-6 were prepared by Ferdinant Wrede while volumes 7-11 by Walther Mitzka. The Deutscher Sprachatlas was, thus, compiled between 1926 and 1956, and presented phonological and grammatical phenomenon occurring across dialects (Zaręba 1974 14, 15

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

).

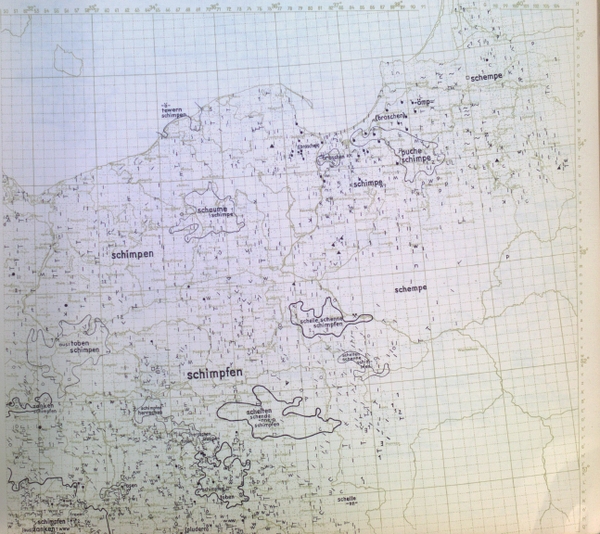

).The geographical distribution of words was prepared mainly by Mitzka who began to send his own questionnaires in 1921. These included 12 sentences (180 words) addressed to informants from chosen places all around Germany. It is through the data gathered between 1939 and 1947 from over 50.000 places that it was possible to create the regional word atlases (Zaręba 1947: 15

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

). The map below, exploring lexical differences across dialects, shows how the word schimpfen ('swear') sounded like in various German-speaking areas, including Silesia.

). The map below, exploring lexical differences across dialects, shows how the word schimpfen ('swear') sounded like in various German-speaking areas, including Silesia.

The local variations of the word schimpfen in German dialects in the Eastern parts of the German-speaking area (Mitzka 1953

Mitzka 1953 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1953 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1953. Deutscher Wortatlas. Band II. Gießen: Wilhelm Schmitz Verlag.

)

)In the 1960s in Marburg two volumes of Günter Bellmann's Schlesischer Sprachatlas were published. They were published, however, in the wrong order - the second volume in 1965 and the first in 1967. Volume I consists of 98 maps focusing on phonology and grammar while the 90 maps of Volume II deal with lexical items which were researched through the use of word questionnaires (Zaręba 1974: 23

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

). The questionnaire consisted of 78 questions regarding lexical items, mostly nouns related to the rural material culture. In 1963 the author sent out the questionnaires to over 3,000 of Mitzka's Silesian informants as well to other informants expelled from the Western parts of Poland all over the German Federal Republic. He received approximately 1,500 answers out of which 762 were used in analysis. Nearly half of the respondents were farmers; the rest consisted of people of various backgrounds, and the elderly who remained scattered all over West Germany for at least 20 years. Based on this data, the author prepared another set of more specific questions for the second volume of his work. 762 informants provided 740 answers (Zaręba 1974: 24

). The questionnaire consisted of 78 questions regarding lexical items, mostly nouns related to the rural material culture. In 1963 the author sent out the questionnaires to over 3,000 of Mitzka's Silesian informants as well to other informants expelled from the Western parts of Poland all over the German Federal Republic. He received approximately 1,500 answers out of which 762 were used in analysis. Nearly half of the respondents were farmers; the rest consisted of people of various backgrounds, and the elderly who remained scattered all over West Germany for at least 20 years. Based on this data, the author prepared another set of more specific questions for the second volume of his work. 762 informants provided 740 answers (Zaręba 1974: 24 Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zaręba 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Zaręba, Alfred 1974. Śląsk w świetle geografii językowej (Biblioteczka Towarzystwa Miłośników Języka Polskiego 20). Wrocław, Warszawa, Kraków, Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

).

).Videos and photographs

The web portal YouTube hosts videos of amateurs reciting Silesian German poetry. One of these amateurs is Horst Jacobowsky who presents the Silesian poems of Ernst Schenke. For every month one poem is published (available via the YouTube profile of Horst Jacobowsky). See the link below for the poem Der Januar [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3_5RneVEBk&list=UUNa55D47y4ZnElM5h2e0Wmw&index=45] and two other poems recited by Jacobowsky - Doas Karrassell and Dar Sperlich - [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XfoJMf9rjJE&list=UUNa55D47y4ZnElM5h2e0Wmw&index=24].Additionally, the YouTube channel offers many other amateur videos filmed in Silesia. See the link for the poem Doas Reißa, recited by Johanes Renner:[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IT7JrfHMxT4].

Yet another video [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UDQuBHNN-mI] presents Johannes Renner telling a story about village children in one of the Silesian dialects (unfortunately, he does not specify which dialect exactly it is). The link below directs to one of Robert Sabel's poem, Der Kaschboam, which he recited himself.

Another piece is Der biese Troom -[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7ifkUujPbk].

The following link contains a poem recited in the Highland dialect by Helmut Nitsche during the celebrations of Tag der Heimat, Homeland Day on the 11th of September 2010. The material was recorded by OstpreussenTV - [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovIbUhR5zTE].

Resources and organizations

1952 saw the establishment of the Deutsche Sozial-Kulturelle Gesellschaft, the German Social-Cultural Association. It has been cooperating with Stiftung Schlesien which collects and publishes materials written in the Silesian German dialects. In 1998 they even organized a poetry competition in which the youth of Liberec in the Czech Republic, Görlitz in Germany and Wrocław in Poland took part (Kryszczuk 1999: 89 Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kryszczuk 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Kryszczuk, Grażyna 1999. Świadomość językowa i kompetencja komunikacyjna Niemców na Dolnym Śląsku. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie.

).

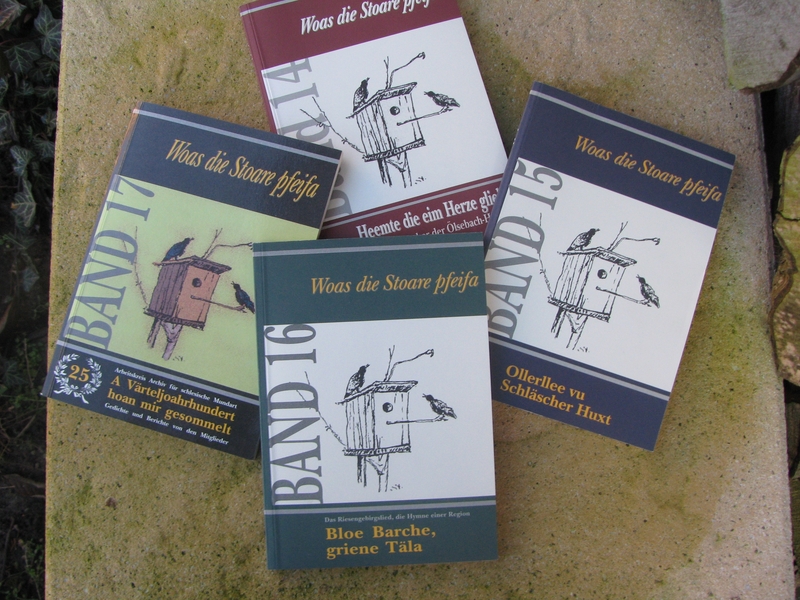

).The Arbeitskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart was founded in 1982 in Baden-Württemberg to develop and protect the Silesian culture and literature, mainly through the organization of meetings and publishing. Their Rundbrief ('circular') gives account of these meetings, presents the figures of Silesian writers and authors, as well as their literary achievements. The association also irregularly publishes volumes as part of their Woas die Staore pfeifa series which focuses on different aspects of Silesian literature. For example, the 1996 publication was dedicated to the poetry of Ernst Schenke, while the 1998 volume discussed Upper Silesian writers (Preuss 2011: 4

Preuss 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Preuss 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Preuss, Friedrich-Wilhelm (red.) 2011. Rundbrief Arbeitskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart 43/2.

). A conference was held by the association in 1996 in Sobótka-Górka/Gorkau, whose crowning moment was unveiling of a memorial plaque by the town hall of Niemcza/Nimptsch dedicated to Erst Schenke (Preuss 2009: 7 ,8

). A conference was held by the association in 1996 in Sobótka-Górka/Gorkau, whose crowning moment was unveiling of a memorial plaque by the town hall of Niemcza/Nimptsch dedicated to Erst Schenke (Preuss 2009: 7 ,8 Preuss 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Preuss 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Preuss, Friedrich-Wilhelm 2009. „Ein schlesisches Herz hat aufgehört zu schlagen“, Schlesische Nachrichten. Zeitung für Schlesien 1. Landmannschaft Schlesien – Nieder- und Oberschlesien.

). During the Wangen in Allgäu spring conference in 2010 virtually every speaker presented a paper in a Silesian dialect. The main theme of the conference was the history of Amalie Preusler and Franz Pohl - a married couple from Szklarska Poręba/Schreiberhau who owned the renowned Josephinenhütte glass factory. The factory brought great fame to Silesia thanks to his wares (Preuss 2011: 3

). During the Wangen in Allgäu spring conference in 2010 virtually every speaker presented a paper in a Silesian dialect. The main theme of the conference was the history of Amalie Preusler and Franz Pohl - a married couple from Szklarska Poręba/Schreiberhau who owned the renowned Josephinenhütte glass factory. The factory brought great fame to Silesia thanks to his wares (Preuss 2011: 3 Preuss 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Preuss 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Preuss, Friedrich-Wilhelm (red.) 2011. Rundbrief Arbeitskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart 43/2.

). One of the aims of Arbeitskreis is the creation of an archive of recordings of those Silesians who still can speak their dialects. The association also postulated that Saxony should apply to UNESCO to put the German Silesian dialects on UNESCO's list of endangered languages (Preuss 2011: 6

). One of the aims of Arbeitskreis is the creation of an archive of recordings of those Silesians who still can speak their dialects. The association also postulated that Saxony should apply to UNESCO to put the German Silesian dialects on UNESCO's list of endangered languages (Preuss 2011: 6 Preuss 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Preuss 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Preuss, Friedrich-Wilhelm (red.) 2011. Rundbrief Arbeitskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart 43/2.

).

).

The Arbeitskreis Archiv für schlesische Mundart – Woas die Stoare pfeifa publishing series (the photography was offered by the president of the association, Friedrich-Wilhem Preuss).

ISO Code

(Lower) Silesian German

ISO-639-3 sli

ISO-639-3 sli

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- Kauder 1937

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- Brockhaus 1997

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- przyp24

- przyp25

- przyp26

- przyp27

- przyp28

- Unwerth 1908

- Jungandreas 1928

- Menzel 1976

- Księżyk 2008

- Kryszczuk 1999

- Wiktorowicz 1997

- Bellmann 1965

- Bellmann 1967

- Bluhme 1964

- Mitzka 1953

- Veith 1971

- Kaczmarczyk 1945

- Brzezina 1989

- Eser 2000

- Morciniec 2002

- Kraft 2001

- Jankowiak 2001

- Kleczkowski 1915

- Weinhold 1853

- Kneip 1999

- Zaręba 1974

- Bogacki 2010

- Pudło 2004

- Biskup 2010

- Sprengel 1994

- Joachimsthaler 2007

- Preuss 2011

- Preuss 2009

- Mitzka 1963-1965

- Ranking dialektów

- Nitschke 2004

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Wiersz Heinricha Tchampela

- Strona tytułowa dramatu De Waber

- Śląskie dialekty języka niemieckiego

- Rozprzestrzenienie (dialektów) języka niemieckiego

- Dialekty niemieckie ok. 1910 roku

- Dialekty łużycko-śląskie na mapie Gwar niemieckich

- apis nutowy do utworu Weihnachtsglocka

- Lautdenkmal

- Oberschlesische Nachrichten

- śląskie niemieckie wykopaliska językowe

- śląskie niemieckie wykopaliska językowe

- Breslausch - dialekt wschodnio-średnio-niemiecki

- Druga kolonizacja niemiecka

- Kolonizacja fryderycjańska i józefińska

- Kształtowanie granic Polski - Górny Śląsk w 1921

- Kierunki osadnictwa niemieckiego 1939-1944

- Średniowieczna kolonizacja niemiecka

- Kartka z 40 zdaniami Wenkera

- Zapis nutowy wiersza Ärndtelied (Pieśń dożynkowa)

- Nuty do wiersza von Holteia i kartka pocztowa

- Lokalne odmiany słowa schimpfen

- Seria wydawnicza Arbeitskreis

- niemieckojęzyczna przeszłość Śląska - Rudy

- niemieckojęzyczna przeszłość Śląska - Bytom