spiskie gwary

Nazwa języka

pol. gwara spiska, gwary spisko-magurskiesłow. spišske nárečie

czes. spišské náreči

ang. Spiš dialects

niem. Mundarten der Region Zips/Zipser Mundarten

Mieszkaniec Spisza (spis. Spis) to Spiszak (spis. Spisok).

Do II wojny światowej w języku polskim funkcjonowały dwie nazwy regionu: Spisz oraz Spiż. Sama etymologia nazwy jest niejasna. Źródła historyczne podają formę łacińską Saepus, Saepusia, zapisywane później przez Słowian Zypus lub Czypis – stąd niemieckie Zips, węgierskie Szepes czy słowackie Spis. Różne koncepcje na temat możliwej etymologii przytacza Bubak (1986: 233

Bubak 1986: 233 / komentarz/comment/r /

Bubak 1986: 233 / komentarz/comment/r / Bubak, Józef 1986. „Polskie gwary spiskie”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury ludowej i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

; Czambel 1906: 11

; Czambel 1906: 11 Czambel 1906: 11 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czambel 1906: 11 / komentarz/comment/r / Czambel, Sam 1906. Slovenská reč a jej miesto v rodine slovanských jazykov. Turčiansky Svätý Martin: nakładem własnym.

).

).Gwary spiskie określa się często mianem gwar spisko-magurskich, od nazwy pasma górskiego – Magury Spiskiej (słow. Spišská Magura), wchodzącej w skład Pogórza Spiskiego.

Lokalizacja – dzisiaj i wcześniej w RP

Spisz jest regionem położonym w Karpatach Zachodnich. Geograficzną granicę Polskiego Spisza wyznacza od zachodu – rzeka Białka Tatrzańska, od południowego wschodu i południa – granica państwowa ze Słowacją, od wschodu i północnego wschodu – rzeka Dunajec , od północy – południowe stoki Gorców, podczas gdy Spisz jako kraina historyczno-kulturowa nie przekracza tu Dunajca. Przyjmuje się, że Polski Spisz to obszar położony między Białką Tatrzańską (na wschód od tej rzeki) i Dunajcem oraz granicą państwową ze Słowacją. Od strony geomorfologicznej zaś kraina ta stanowi wschodnią część Podhala.Polski Spisz zajmuje północny fragment Zamagurza Spiskiego – obszaru rozciągającego się na północ od pasma Magury Spiskiej. Zarówno to pasmo, jak i większość Zamagurza Spiskiego znajduje po słowackiej stronie granicy. Spisz jako całość obejmuje następujące tereny: południowo-wschodnią część Podhala, kotlinę górnego Popradu i Góry Lewockie, kotlinę górnego Hornadu oraz Rudawy Spiskie.

Obszar całego Spisza wynosi ok. 3700 km2, z czego 3500 km2 należy do Słowacji (245 000 ludności), a zaledwie 195,5 km2 do Polski (z liczbą 12 000 mieszkańców w 1970 r. i 11 500 w 1978 r.) (Biały 1986: 7ff

Biały 1986: 7ff / komentarz/comment/r /

Biały 1986: 7ff / komentarz/comment/r / Biały, Zbigniew 1986. „Polski Spisz. Historyczne uwarunkowania kultury ludowej tego regiony i sposoby jej badania po II wojnie światowej”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury ludowej i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

; Górka i Biały 1986: 145

; Górka i Biały 1986: 145 Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Górka, Zygmunt i Zbigniew Biały 1986. „Zarys problematyki ekonomiczno-geograficznej polskiego Spisza”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

).

Mapa Spisza.

(red. mapy Jacek Cieślewicz, na podstawie: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Slovakia_Spis.gif)

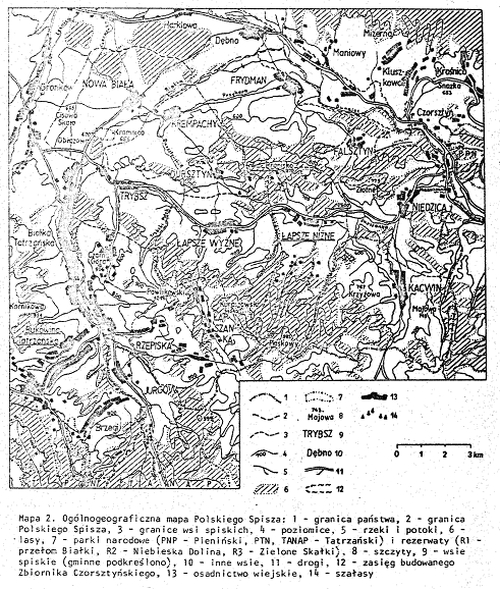

Mapa ogólnogeograficzna polskiego Spisza autorstwa Zygmunta Górki i Zbigniewa Białego (Górka i Biały 1986: 147

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Górka, Zygmunt i Zbigniew Biały 1986. „Zarys problematyki ekonomiczno-geograficznej polskiego Spisza”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

).

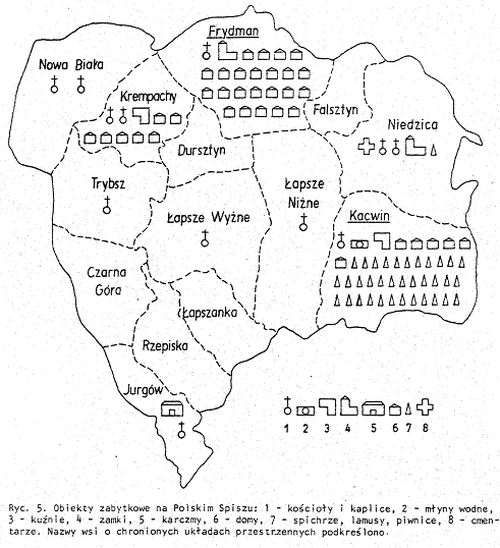

Mapa zabytków polskiego Spisza autorstwa Zygmunta Górki i Zbigniewa Białego (Górka i Biały 1986: 180

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Górka, Zygmunt i Zbigniew Biały 1986. „Zarys problematyki ekonomiczno-geograficznej polskiego Spisza”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

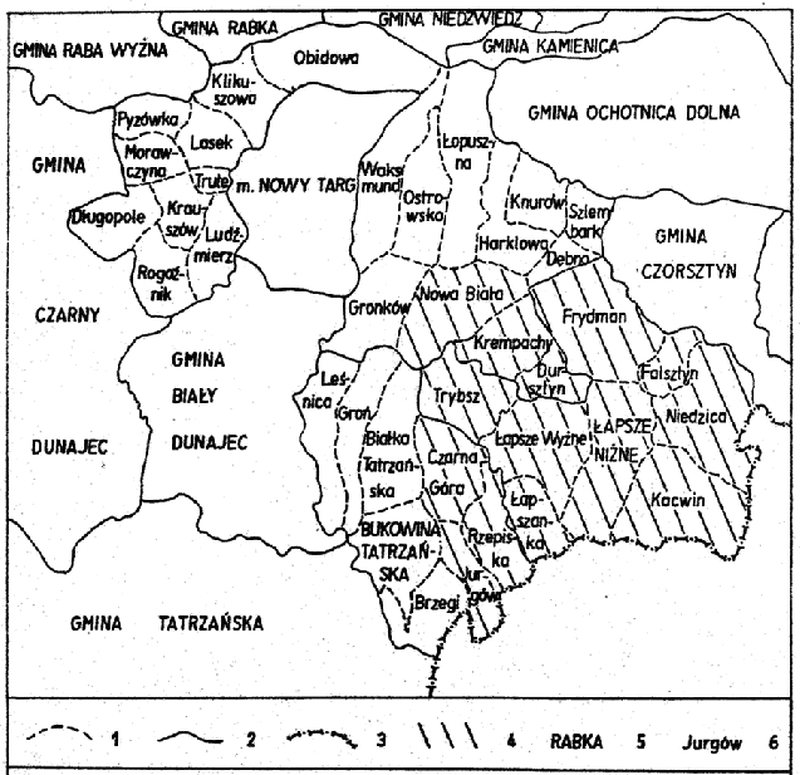

).Polski Spisz nie stanowi samodzielnej jednostki administracyjnej – składa się z trzech gmin, w skład których wchodzi łącznie 14 wsi:

- gmina Bukowina Tatrzańska (powiat tatrzański):

- Czarna Góra (słow. Čierna Hora),

- Jurgów (Jurgov),

- Rzepiska (Repiská),

- gmina Łapsze Niżne (powiat nowotarski, jedyna w całości leżąca na Polskim Spiszu):

- Falsztyn (Falštín),

- Frydman (Fridman),

- Kacwin (Kacvín)

- Łapszanka (Lapšanka),

- Łapsze Niżne (Nižné Lapše),

- Łapsze Wyżne (Vyšné Lapše),

- Niedzica (Nedeca),

- Trybsz (Tribš),

- gmina Nowy Targ (powiat nowotarski):

- Dursztyn (Durštín),

- Krempachy (Krempachy),

- Nowa Biała (Nová Belá).

Polski Spisz. (źródło: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Polski_Spisz_1.svg)

Podział administracyjny polskiego Spisza autorstwa Zygmunta Górki (Górka i Biały 1986: 146

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Górka i Biały 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Górka, Zygmunt i Zbigniew Biały 1986. „Zarys problematyki ekonomiczno-geograficznej polskiego Spisza”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

).

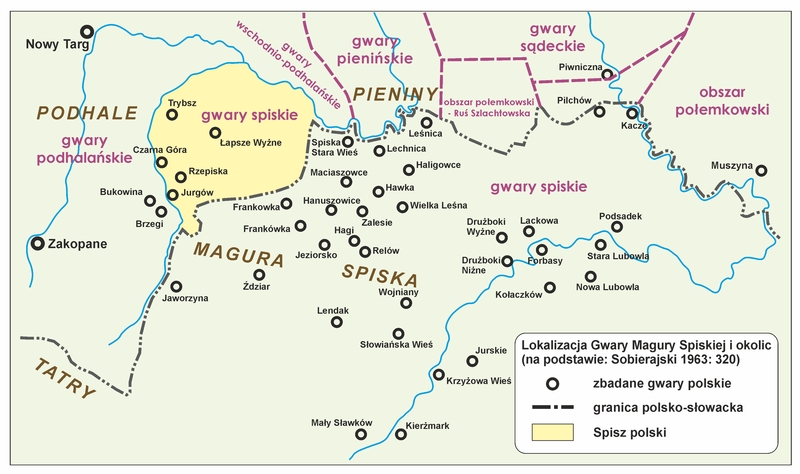

Spisz w Polsce i na Słowacji (red.mapy Jacek Cieślewicz, na podstawie: Sobierajski 1963: 320

Sobierajski 1963: 320 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sobierajski 1963: 320 / komentarz/comment/r / Sobierajski, Zenon 1963. „Z morfologicznych wpływów słowackich na polskie gwary spiskie”, w: Z polskich studiów slawistycznych. Warszawa: PWN.

, Atlas polskich gwar spiskich na terenie Polski i Czechosłowacji. T. I, Poznań 1966, s. 4) [1]

, Atlas polskich gwar spiskich na terenie Polski i Czechosłowacji. T. I, Poznań 1966, s. 4) [1] przyp01 / komentarz/comment /

przyp01 / komentarz/comment / Mapka pochodzi ze strony: http://www.gwarypolskie.uw.edu.pl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=401&Itemid=18

Lokalizacja – poza Rzeczpospolitą

Słowacka część Spisza cechuje się stosunkowo dużą liczbą miast i miasteczek (najważniejszymi miejscowości są: Poprad, Spiska Nowa Wieś i Kieżmark), natomiast w polskiej części Spisza nie ma ani jednego ośrodka miejskiego. Miastem spiskim położonym najbliżej granicy Polskiego Spisza (od północnego wschodu) jest Spiska Stara Wieś, znajduje się w pobliżu Dunajca (naprzeciw Sromowców Wyżnych); ze wsi Polskiego Spisza najbliżej tego miasta położona jest (w sensie dostępności komunikacyjnej) Niedzica, którą dzieli od niego kilka kilometrów okrężnej drogi (biegnącej przeważnie wzdłuż Dunajca, po obecnej słowackiej stronie tej rzeki).Słowacki Spisz jest częścią dawnego kraju wschodniosłowackiego, a obecnie stanowi zachodnią część kraju preszowskiego – jednej z 8 jednostek administracyjnych, na które podzielona jest Słowacja (obok: zachodniosłowackiego i środkowosłowackiego) (Biały 1986: 9

Biały 1986: 9 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biały 1986: 9 / komentarz/comment/r / Biały, Zbigniew 1986. „Polski Spisz. Historyczne uwarunkowania kultury ludowej tego regiony i sposoby jej badania po II wojnie światowej”, w: Zbigniew Bialy (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury ludowej i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

).Same polskie gwary spiskie przekraczają polsko-słowacką granicę polityczną i sięgają daleko w głąb kraju – ich zwarty zasięg przekracza pasmo Magury Spiskiej, a wyspowo występują w okolicy Starego Lubowia i Kieżmarku. Na Słowackim Spiszu znajdują się 34 miejscowości, których mieszkańcy posługują się niemal wyłącznie językiem polskim (w powiatach: Spiska Stara Wieś, Stara Łubowna, Kieżmark i w powiecie Wysokie Tatry) (Biały 1986: 9

Biały 1986: 9 / komentarz/comment/r /

Biały 1986: 9 / komentarz/comment/r / Biały, Zbigniew 1986. „Polski Spisz. Historyczne uwarunkowania kultury ludowej tego regiony i sposoby jej badania po II wojnie światowej”, w: Zbigniew Bialy (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury ludowej i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

).

Południowy zasięg języka polskiego (zwarty obszar i enklawy) - red.mapy Jacek Cieślewicz.

Historia

Obszary dzisiejszego Polskiego Spisza do XI lub XII w. prawdopodobnie należały do Polski, od momentu gdy Mieszko I zwrócił się przeciwko Czechom i wcielił ziemie Wiślan oraz Śląsk do swego państwa. W ten sposób Karpaty, stanowiące wcześniej granicę Czech i Węgier, zaczęły wyznaczać granicę polsko-węgierską (Sobczyński 1986 Sobczyński 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sobczyński 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Sobczyński, Marek (1986). Kształtowanie się karpackich granic Polski (w X–XX w.). Łódź: Zarząd Wojewódzki PTTK – Regionalna Pracownia Krajoznawcza. URL: http://geopol.geo.uni.lodz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/granice_karpackie.pdf [dostęp: 10.10.2012 r.]

).

).Następnie tereny te przeszły pod władanie Królestwa Węgier. Zasiedlone zostały przez rodzinę Berzeviczych z Lomnicy, która w 1209 r. otrzymała tereny od rzeki Poprad aż po Tatry (nazywane wówczas: Górami Śnieżnymi). Ośrodkiem władzy na Zamagurzu stał się zamek w Niedzicy, wzniesiony około 1320 r. przez ten ród, który władał zachodnim Zamagurzem do początku XVI w.

W czasach anarchii na Węgrzech wywołanej klęską w bitwie z Imperium Osmańskim pod Mohaczem oraz wojną domową pomiędzy pretendentem do tronu Ferdynandem Habsburgiem a Janem Zapolyą tereny Spisza przechodziły z rąk do rąk. W drugiej połowie XVI w. władali tymi obszarami także polscy magnaci – Hieronim Łaski, a po nim jego syn Olbracht Łaski, występując zawsze jako poddani króla Węgier. Ten ostatni sprzedał swoje prawa do Zamagurza Jerzemu Horvathowi z Palocsy i to jego rodzina rządziła regionem przez kolejne stulecie. Pod koniec XVII w., w wyniku wojen religijnych i powstań antyhabsburskich na Węgrzech, Zamagurze przeszło pod władzę rodu Giovanellich. Dopiero w 1776 r., po definitywnym objęciu władzy na Węgrzech przez Habsburgów, Zamagurze wróciło w ręce Horvathów. Od połowy XIX w., po likwidacji stosunków feudalnych, majątki szlacheckie na Zamagurzu stały się własnością węgierskiego rodu Salamonów (w Niedzicy) i niemieckiego rodu Jungenfeldów (w Falsztynie i Łapszach Niżnych), którzy pozostali na tych terenach aż do II wojny światowej.

Do czasu I wojny światowej Spisz (tak samo jak Orawa) należał w całości do Królestwa Węgier. W 1920 r. dokonano podziału tej krainy (wraz z Orawą) pomiędzy Polskę i Czechosłowację wzdłuż linii w przybliżeniu odpowiadającej współczesnej polsko-słowackiej granicy państwowej (Biały 1986: 7ff

Biały 1986: 7ff / komentarz/comment/r /

Biały 1986: 7ff / komentarz/comment/r / Biały, Zbigniew 1986. „Polski Spisz. Historyczne uwarunkowania kultury ludowej tego regiony i sposoby jej badania po II wojnie światowej”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury ludowej i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

).

).

Terytorium Galicji przed I wojną światową.

Różowa linia oddziela część polską od słowackiej. Nazwy polskie (i ukraińskie).

Brak informacji o prawach autorskich. http://donhoward.net/genpoland/gal.htm

Dla polskiej części Spisza w okresie międzywojennym głównym miastem był (i w dużej mierze nadal jest) Nowy Targ. Do wybuchu I wojny światowej, gdy Spisz znajdował się w granicach Węgier, miasto to było często odwiedzane przez mieszkańców obecnego Polskiego Spisza (granica pomiędzy Królestwem Węgierskim a Królestwem Galicji i Lodomerii miała charakter przede wszystkim celny i administracyjny). W Nowym Targu bowiem odbywały się istotne dla okolicznej ludności jarmarki, w których uczestniczenie wrosło też w gospodarczą i w ogóle kulturową tradycję Polskiego Spisza; jednocześnie mieszkańcy tego obszaru udawali się na jarmarki do miast Górnego Spisza.

W dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym i po wojnie, aż do momentu zlikwidowania w Polsce powiatów (1975 r.), miasto to było dla Polskiego Spisza ośrodkiem administracji średniego (powiatowego) szczebla, na krótki okres zostając gminą (Biały 1986: 8f

Biały 1986: 8f / komentarz/comment/r /

Biały 1986: 8f / komentarz/comment/r / Biały, Zbigniew 1986. „Polski Spisz. Historyczne uwarunkowania kultury ludowej tego regiony i sposoby jej badania po II wojnie światowej”, w: Zbigniew Biały (red.) Polski Spisz. Jedność kultury i jej historyczne uwarunkowania. Środowisko naturalne – warunki gospodarowania. Antropologia. Gwary, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego DCCCXI, Prace Etnograficzne, Zeszyt 22, Studia Spiskie nr 1. Kraków: Nakładem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

). Obecnie Nowy Targ jest stolicą powiatu nowotarskiego.

). Obecnie Nowy Targ jest stolicą powiatu nowotarskiego.

Mapa polskiego Spisza z 1938 r. (źródło: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Spisz_1938.jpg)

Zwarte, autochtoniczne osadnictwo polskie na obszarze północnego i środkowego Spisza datowane jest odpowiednio na XIII–XV w. Ludność polską na obszarze Orawy i Spisza cechuje dynamika demograficzna wyższa niż średnia dla Słowacji, co do pewnego stopnia rekompensuje procesy asymilacyjne, jakim podlegają Polacy (Skawiński 2009

Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Skawiński, Marek 2009. Polacy na Słowacji. URL: http://www.polskiekresy.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=161:polacy-na-slowacji2&catid=109:etnografia&Itemid=509 [dostęp:26.09.2012 r.]

).

).Kod ISO

brak kodu

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- Bubak 1986: 233

- Czambel 1906: 11

- Biały 1986: 7ff

- Górka i Biały 1986

- Sobierajski 1963: 320

- Biały 1986: 9

- Sobczyński 1986

- Biały 1986: 8f

- Skawiński 2009

- Sowa 2002: 132f

- Budz 2011

- Sikora 2006: 51ff

- Biały 1986: 10f

- Bubak: 234f

- Sobierajski 1966: 84–88

- Bubak 1986: 242ff

- Sobierajski 1966: 80f

- Sobierajski 1963: 329

- Moskal 2004: 11

- Małecki 1938

- Moskal 2004: 2

- Biały 1986: 16

- Biały 1986: 15f

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Mapa Spisza w Polsce i na Słowacji

- Mapa Spisza

- Południowy zasięg języka polskiego

- Mapa polskiego Spisza Górki i Białego

- Mapa zabytków polskiego Spisza Górki i Białego

- Polski Spisz

- Podział administracyjny polskiego Spisza Górki

- Terytorium Galicji przed I Wojną Światową

- Mapa polskiego Spisza z 1938 r

- Zróżnicowanie polskich gwar 1

- Zróżnicowanie polskich gwar 2

- Zróżnicowanie polskich gwar 3

- Atlas slovenskeho jazyka

- Szablon dialektów słowackich