Podlachian and West Polesian

Name

Endonyms

The varieties discussed here are not a homogeneous whole. There are many different or optional names related to specific locations (eg. kornicka havorka, pudlaśka mova), characteristics of speech (chmacka), ethnicity (ruska mova, po chachłaćki 'Ruthenian speech') or highlighting the local nature of the variety (po prostu 'just simple speech', tutejša mova 'speech from here'), or po naszomu (‘in our way’), po swojomu (‘in our own way’). Speakers of Belarusian varieties consider their mother tongue as Belarusian, while speakers who consider themselves Ukrainians identify their mother tongue as Ukrainian (SIL 2011: 2 SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

).

). Exonyms

Polish exonyms

In the Lublin region the dialect of Podlasie is defined as ‘chachłacki’, which, depending on the environment is characterized as a neutral or negative term. In this way southern dwellers define the language of the north. The inhabitants of Lublin define it as a simple dialect, the ‘lesser chachłacki dialect’ (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XXIV Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

). The speakers themselves perceive the same term as neutral (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XXIV

). The speakers themselves perceive the same term as neutral (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XXIV Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

). Jan Maksymiuk, the Podlasie analyst at Radio Free Europe, located at the Podlasie Svoja.org and which promotes the standardization of language varieties, calls it in Polish the Podlaski language.

). Jan Maksymiuk, the Podlasie analyst at Radio Free Europe, located at the Podlasie Svoja.org and which promotes the standardization of language varieties, calls it in Polish the Podlaski language.Other exonyms

The English names for the varieties are Podlachian (Podlasie) and for Polesie (West) Polesian or Polisian (probably influenced by the Ukrainian term поліські).Podlaskie Ukrainian language varieties are referred to as підляські говірки, sometimes сідлецькі ('Siedlce') (Łesiw 1997: 279

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

).

). In the nineteenth century, Polesie language varieties were identified by the Russian committee appointed in relation to the population census as the ‘małorusko-polesko-Belarusian’ language (Wysocki 2005: 121

Wysocki 2005 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wysocki 2005 / komentarz/comment/r / Wysocki, Aleksander 2005. „Zarys problemu świadomości narodowej rdzennych mieszkańców województwa poleskiego w świetle dokumentów Centralnego Archiwum Wojskowego”, Biuletyn Wojskowej Służby Archiwalnej 27: 120-135.

). There is also a lot of terms created from each village, which if necessary are used as a description of the varieties (eg the Radzyński dialect, радинский говор) (Łesiw 1997: 283

). There is also a lot of terms created from each village, which if necessary are used as a description of the varieties (eg the Radzyński dialect, радинский говор) (Łesiw 1997: 283 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

).

).

Tourist sign-posts in Podlachian and Polish

[by Renessaince (own work) GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons].

History and Geopolitics

Location in the Polish Republic

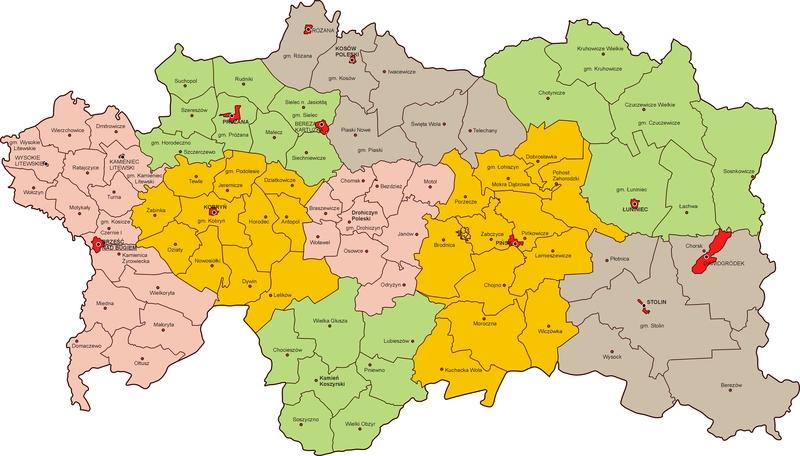

The Polesie Region in the Second Republic [by Poznaniak (CC-BY-SA-2.5 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5), via Wikimedia Commons].

Area I of the Republic includes not the only dialect of Podlasie, but practically the whole area of Polesie region. In the interwar period, both significant part Polessye and Podlasie lay within Polish borders. After World War II, Poland included only Podlasie.

Michał Łesiów defines the area of the Podlasie dialect as located on the Narew River in the northern edge of the former province of Chelm (Łesiw 1997: 277

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

). The Podlasie variety forms part of the Polesian dialect according to Konstantin Michalczuk (cf. Łesiw 1997: 281

). The Podlasie variety forms part of the Polesian dialect according to Konstantin Michalczuk (cf. Łesiw 1997: 281 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

).

).

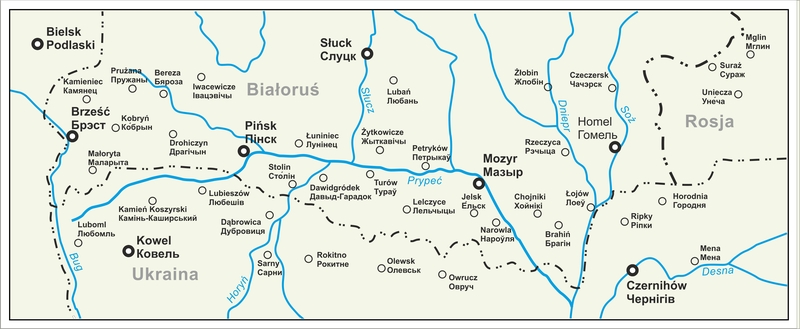

Map of Polesia (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Wiarenicz 2009: 22

Wiarenicz 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiarenicz 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Вяреніч, Вячаслаў Л. [Wiarenicz] 2009. Палескі архіў. Минск: А.Н. Вараксин.

).

).

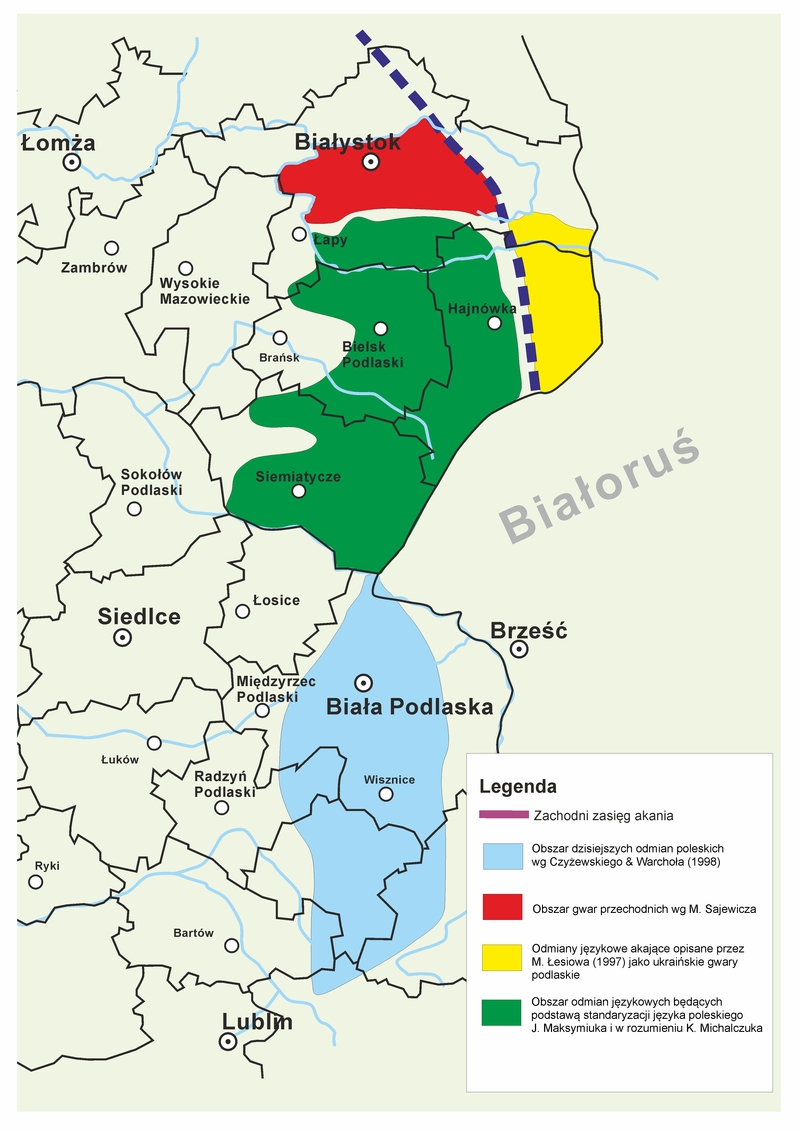

Transient dialects of Polish-Belarusian-Ukrainian and Polesie – map ed.: Jacek Cieslewicz.

Głuszkowska says (2001: 81

Głuszkowska 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Głuszkowska 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Głuszkowska, Jadwiga 2001. „Wschodniosłowiańskie elementy językowe w folklorze podlaskim”, w: Elżbieta Smułkowa & Anna Engelking (red.) Język i kultura białoruska w kontakcie z sąsiadami. Warszawa: Wydział Polonistyki UW, s. 81-92.

), that the transitional dialect Belarusian-Ukrainian corridor is located in the Podlasie region, south of the Bialystok forests. In turn, Sajewicz (1997

), that the transitional dialect Belarusian-Ukrainian corridor is located in the Podlasie region, south of the Bialystok forests. In turn, Sajewicz (1997 Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

) distinguishes the transitional dialects according to the soft consonants used (see map).

) distinguishes the transitional dialects according to the soft consonants used (see map).Other locations

Today, in addition to the Polesie language varieties used in Poland they are also used in Ukraine (Volyn) and Belarus (near Brest) (Duliczenko 2002: 581 Duliczenko 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duliczenko 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Duličenko, Aleksandr D. 2002. „Westpolesisch”, w: Miloš Okuka (red.) Lexikon der Sprachen des europäischen Ostens. Klagenfurt, s. 581-588. [http://wwwg.uni-klu.ac.at/eeo/]

).

).History and origin

Even before the Union of Lublin (the act of forming the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) the land north of Włodawka belonged to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The area passed in 1569 to the Polish Crown (Pazdniakou 2007: 384-385 Pazdniakou 2007 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pazdniakou 2007 / komentarz/comment/r / Пазднякоў, Валерый [Pazdniakou] 2007. „Падляшскае ваяводства”, w: Г. П. Пашкоў et al. (red.) Вялікае Княства Літоўскае. Энцыклапедыя. Т. 2. Мінск: Беларуская энцыклапедыя имя Петруся Броўкі, s. 384-385.

). The southern part of the area remained in Lithuania, however, and Polish settlements were intensified here. At the same time on the left bank of the river Bug Russian settlements developed, supported by Lithuanian magnates (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: IX-X

). The southern part of the area remained in Lithuania, however, and Polish settlements were intensified here. At the same time on the left bank of the river Bug Russian settlements developed, supported by Lithuanian magnates (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: IX-X Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

).

).According to Fałowski (2011: 132-134

Fałowski 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Fałowski 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Fałowski, Adam 2011. „Język ukraiński”, w: Barbara Oczkowa & Elżbieta Szczepańska (red.) Słowiańskie języki literackie. Rys historyczny. Kraków: UJ, s. 127-160.

), in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries across the Eastern Slavic area, located within the Commonwealth, there appeared in numerous publications (including translations of the Bible) the so-called "simple speech", known today as the "literary and cross-regional developed variant of Belarusian and Ukrainian." Although researchers do not agree on the written variety of language as used in contemporary speech dialects, they do generally emphasize the presence of Polish, Church Slavonic and Ruthenian elements.

), in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries across the Eastern Slavic area, located within the Commonwealth, there appeared in numerous publications (including translations of the Bible) the so-called "simple speech", known today as the "literary and cross-regional developed variant of Belarusian and Ukrainian." Although researchers do not agree on the written variety of language as used in contemporary speech dialects, they do generally emphasize the presence of Polish, Church Slavonic and Ruthenian elements.In the villages of Lublin, Polish and Ruthenian were spoken, with a predominance of Ruthenian. The Union of Lublin and Brest initiated the Polonization of the nobility. In addition, schools of the Uniate church educated the intellectual elite to handle both Polish and Ukrainian (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XI

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

).

). During the partitions, the former Republic of Russia promoted Uniate Orthodoxy among the population, counting on subsequent Russification. In the Lublin region, however, these actions were counterproductive and led to the crystallization of a Polish national consciousness (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XIII

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

). There was also a tendency to adopt the Polish language, related to factors such as a change to the Latin rite and intermarriage. In 1875 the union was liquidated. In southern Podlasie, the Uniates did not want to go over to Orthodoxy - seen as the religion of the invaders – so they switched to Roman Catholicism. All things Russian and East Slavic were abandoned: language, dress and customs. This was strengthened by the state language policy, which treated as a minor dialect any variant of the Russian language (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XIV-XV

). There was also a tendency to adopt the Polish language, related to factors such as a change to the Latin rite and intermarriage. In 1875 the union was liquidated. In southern Podlasie, the Uniates did not want to go over to Orthodoxy - seen as the religion of the invaders – so they switched to Roman Catholicism. All things Russian and East Slavic were abandoned: language, dress and customs. This was strengthened by the state language policy, which treated as a minor dialect any variant of the Russian language (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XIV-XV Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

).

). In 1905, an edict on religious tolerance was announced, allowing former administrative of conservative Uniates to move from Orthodoxy to Catholicism. This resulted in a rapid, massive Polonization to the left of the Bug (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XV

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

).

).

Odmiany Podlachian and Polesian mapped as dialects of Ukrainians [map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/picturedisplay.asp?linkpath=pic\D\I\Dialects_Map.jpg)].

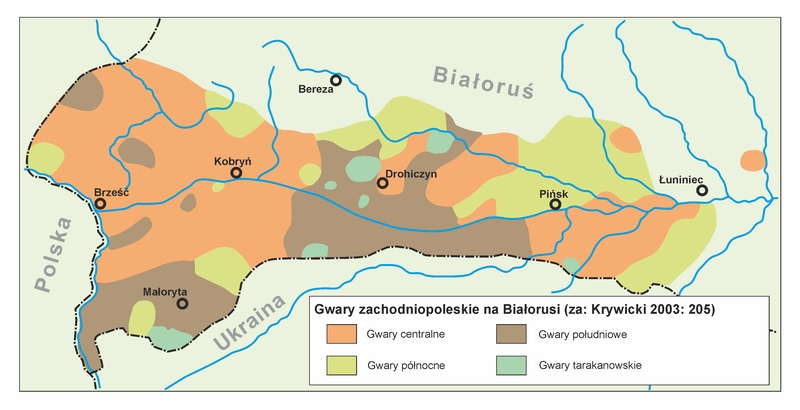

Western Poleski dialect in Belarus (map ed.: Jacek Cieslewicz, based on: Krywicki 2003: 205

Krywicki 2003 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krywicki 2003 / komentarz/comment/r / Kрывіцкі, Аляксандр А. [Krywicki] 2003. Дыялекталогія беларускай мовы. Мінск: Вышэйшая школа.

).

).The Bialystok area was not affected by “Operation Vistula", aimed at resettlement of the population considered to be Ukrainian. In the southern Podlasie region in the years 1944-1947 the Ukrainian population was deported initially to Ukraine, then into the western and northern regions under “Operation Vistula". In the 1940s only the Polish population inhabited the eastern Lublin region. Former residents were allowed to return only after 1957 (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XX-XXI

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

).

).

ISO Code

no code

in 2011, Jan Maksymiuk applied for a ISO 639-3 code for the Podlachian languages - the application was rejected (SIL 2011 SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

).

).

The Ethnologue refers to transitional Belarusian-Ukrainian dialects (Lewis 2009 Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).

UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger mentions Polesian as a vulnerable language.

The Linguascale encodes all Belarusian-Ukrainian transitional and Polesian varieties with: 53-AAA-edd.

in 2011, Jan Maksymiuk applied for a ISO 639-3 code for the Podlachian languages - the application was rejected (SIL 2011

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

).

). The Ethnologue refers to transitional Belarusian-Ukrainian dialects (Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger mentions Polesian as a vulnerable language.

The Linguascale encodes all Belarusian-Ukrainian transitional and Polesian varieties with: 53-AAA-edd.

- Hawryluk 1988

- SIL 2011

- Lewis 2009

- Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998

- Łesiw 1997

- Wysocki 2005

- Głuszkowska 2001

- Sajewicz 1997

- Duliczenko 2002

- Pazdniakou 2007

- Krywicki 2003

- Hawryluk [?]

- Łesiów 1994

- Maksimiuk 2009

- Michaluk 2010

- Chmielewski 2010

- Kruk 1997

- Mironowicz 2010

- Borciuch i Olejnik 2001

- Antonowicz 1968

- Arkuszyn 2010

- Pawluczuk 1972

- Małecki 2004

- Warchoł 1992

- Smułkowa 2002

- Fionik i Wrubl'ewski 2006

- Tołstoj 1968

- Łapicz 1986

- Klimczuk 2010

- Fałowski 2011

- Fionikowie 2008

- Hlebowicz 2008

- Warchał 1992

- Leończuk 2008

- Stachwiuk 2006

- Kondratiuk 1972

- Sawicka i Wróblewski 1972

- Fionik 2011

- Wiarenicz 2009

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- I.Ignatiuk "Ukraińskie gwary południowego Podlasia

- M.Sarnac'ka - "Pukłunysja swujuj zymli"

- Tablice turystyczne po podlasku i po polsku

- Województwo poleskie w II Rzeczypospolitej

- Mapa Polesia

- Odmiany podlaskie i poleskie

- Gwary zachodniopoleskie na Białorusi

- Przykład ortografii w czasopiśmie Bielski Hostineć

- Użycie alfabetu łacińskiego w ortografii

- Tekst wschodniosłowiański pismem arabskim

- Banner pochodzący z 'Howorymo po swojomu'

- Banner pochodzący z 'Howorymo po swojomu'

- Strona tytułowa podlaskich czytanek dla dzieci

- Tablica w podlaskiej odmianie językowej

- Okładka płyty Піесні спуд Jанова.

- Przejściowe dialekty polsko-białorusko-ukraińskie

- Izoglosy białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej

- Schematyczna granica językowa białorusko-ukraińska