Podlachian and West Polesian

Kinship and identity

Discussed here are the dialects belonging to the East Slavic languages, as well as Ukrainian and Belarusian. Dialects are sometimes classified as Podlasie ans Polesie.Belarusian and Podlasie dialects are mutually intelligible (SIL 2011: 4

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

). The poet Yuri Hawryluk believes that Podlasie dialects are comprehensible "without any great effort” for speakers of Ukrainian dialects (Hawryluk [?]

). The poet Yuri Hawryluk believes that Podlasie dialects are comprehensible "without any great effort” for speakers of Ukrainian dialects (Hawryluk [?] Hawryluk [?] / komentarz/comment/r /

Hawryluk [?] / komentarz/comment/r / Гаврилюк, Юрій [Hawryluk] [?]. „Українці і білоpуська проблема на Підляшші. Міфи і факти”, Гайдамака. [http://www.haidamaka.org.ua/0109.html]

).

).Language or dialect?

Polesie Language Varieties have been described as both Belarusian (Krywicki 2003: 214 Krywicki 2003 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krywicki 2003 / komentarz/comment/r / Kрывіцкі, Аляксандр А. [Krywicki] 2003. Дыялекталогія беларускай мовы. Мінск: Вышэйшая школа.

) and as Ukrainian (Łesiw 1997: 281

) and as Ukrainian (Łesiw 1997: 281 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

). As discussed in this profile Michał Łesiów describes them as a dialect of Ukrainian (Łesiw 1997: 277

). As discussed in this profile Michał Łesiów describes them as a dialect of Ukrainian (Łesiw 1997: 277 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

). Due to the lack classification in the mid-nineteenth century, the dialect of the North Podlasie region in the vicinity of Narew and Bielsko was defined as Ukrainian - has been defined as a korolowski (Crown) dialect (Łesiów 1994: 119-120

). Due to the lack classification in the mid-nineteenth century, the dialect of the North Podlasie region in the vicinity of Narew and Bielsko was defined as Ukrainian - has been defined as a korolowski (Crown) dialect (Łesiów 1994: 119-120 Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Łesiów, Michał 1994. „Gwary ukraińskie między Bugiem i Narwią”, Białostocki Przegląd Kresowy II: 117-137.

na podstawie profilu białoruskiego.

).

).Konstantin Michalczuk considered that there were two types of Podlasie variants (подляшское поднаречие), distinguishing between the two types (разноречия) thus:

- Podlaski dialect proper - in addition to the contemporary (1877) counties of Drohiczyń and Bielski as confined by the rivers Bug and Narew.

- korolowski - part of the Bialystok region limited by the rivers Bug and Narew (Łesiw 1997: 282

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів. ).

).

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). The biggest controversy concerns membership of the Polesie linguistic term Polesie (Brest-Pinsk) and northern Podlaskie (Bialystok) (Sajewicz 1997: 97

). The biggest controversy concerns membership of the Polesie linguistic term Polesie (Brest-Pinsk) and northern Podlaskie (Bialystok) (Sajewicz 1997: 97 Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). According to M. Sajewicz even sharing the majority Ukrainian vocabulary does not preclude the dialect belonging to the Ukrainian language, not Belarusian. The researcher investigated the Bialorusian dialect, which has penetrated the system feature, such as the ‘hard’ pronunciation of consonants. Among the features endowed with more "forceful Bialorusification" Sajewicz mentions the pronunciation of ‘dziekanie, ciekanie, akanie, zmiękczanie’ and the softening of consonants before [e] and hard [c] (Sajewicz 1997: 98-99

). According to M. Sajewicz even sharing the majority Ukrainian vocabulary does not preclude the dialect belonging to the Ukrainian language, not Belarusian. The researcher investigated the Bialorusian dialect, which has penetrated the system feature, such as the ‘hard’ pronunciation of consonants. Among the features endowed with more "forceful Bialorusification" Sajewicz mentions the pronunciation of ‘dziekanie, ciekanie, akanie, zmiękczanie’ and the softening of consonants before [e] and hard [c] (Sajewicz 1997: 98-99 Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). The scholar points to the link with the history of Belarus and Ukrainian settlement in these areas (Sajewicz 1997: 102

). The scholar points to the link with the history of Belarus and Ukrainian settlement in these areas (Sajewicz 1997: 102 Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

).

).

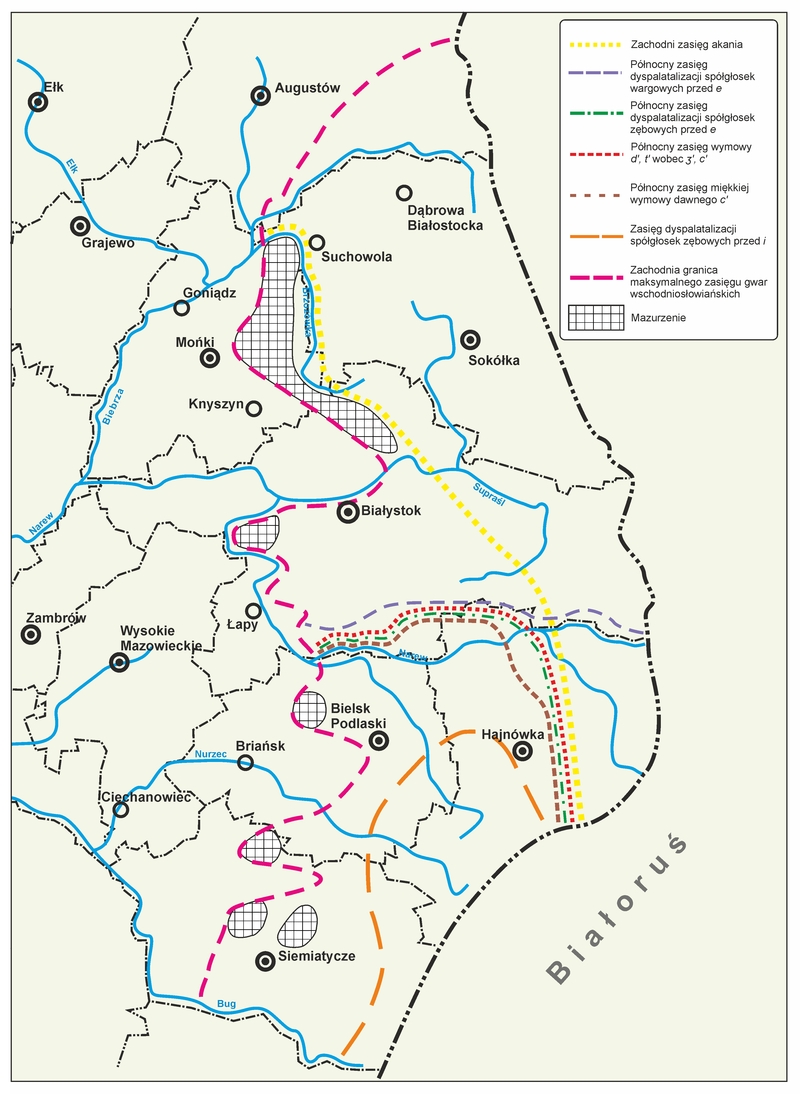

Isoglosses used to determine the Belarusian-Ukrainian language boundary (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, based on: Sajewicz 1997: 107

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

).

).

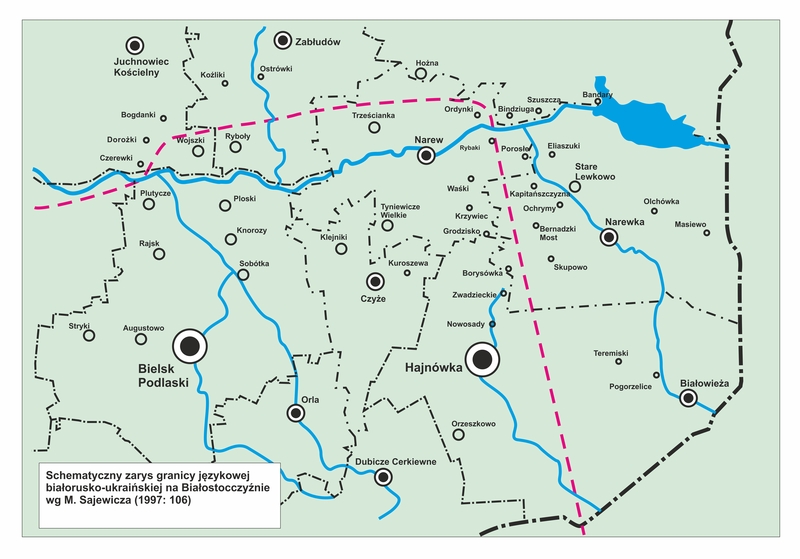

Schematic borderline between Belarusian and Ukrainian in the region of Białystok according to M. Sajewicz (1997: 106

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

) - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz.

) - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz.Language status & attitudes

In the interwar period, Władysław Kuraszkiewicz drew attention to the lack of awareness of speakers have of some dialects of Podlasie (Łesiów 1994: 122 Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Łesiów, Michał 1994. „Gwary ukraińskie między Bugiem i Narwią”, Białostocki Przegląd Kresowy II: 117-137.

na podstawie profilu białoruskiego.

). Jan Maksymiuk says that speakers of Podlasie Belarusians dialects identify their mother tongue as Belarusian, while speakers who consider themselves Ukrainians identify their mother tongue as Ukrainian (SIL 2011: 2

). Jan Maksymiuk says that speakers of Podlasie Belarusians dialects identify their mother tongue as Belarusian, while speakers who consider themselves Ukrainians identify their mother tongue as Ukrainian (SIL 2011: 2 SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

). Michal Lesiow has said in turn that the national consciousness in the Bialystok region was shaped not only by the criterion of language (Łesiów 1994: 127

). Michal Lesiow has said in turn that the national consciousness in the Bialystok region was shaped not only by the criterion of language (Łesiów 1994: 127 Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Łesiów, Michał 1994. „Gwary ukraińskie między Bugiem i Narwią”, Białostocki Przegląd Kresowy II: 117-137.

na podstawie profilu białoruskiego.

).

).North Podlasie area was not affected in 1947 by "Operation Vistula", which was to resettle Ukrainians, since East Slavic inhabitants were considered Belarusians (Łesiów 1994: 123-124

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Łesiów, Michał 1994. „Gwary ukraińskie między Bugiem i Narwią”, Białostocki Przegląd Kresowy II: 117-137.

na podstawie profilu białoruskiego.

).

).Jan Maksymiuk believes that Belarusians have more than one national language. In addition to the Belarusian lists: Polesie (poliêśka / polišućka mova), and among Belarusians in Poland Podlasie (pudlaśka mova), he points out the fact that language is the Podlasie twin sister (sestra-blizniačka) of the Polesie language, and the translation from one to the other is merely a change in phonetics ("poliêśki original I simply» žyvciom «perepisav našoju fonetykoju ") (Maksimjuk 2009

Maksimiuk 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Maksimiuk 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Maksimiuk, Jan 2009. „Biłoruśku klasyku vpuskajemo perednimi dveryma”, Svoja.org. [http://svoja.org/1210.html?jn553eedc4=1#jotnav553eedc4b4109e9fda286a892e61081d]

).

).In the days of the Russian Empire distinguished researchers in Belarus discovered distinctive language and customs in a variety of regions (Michaluk 2010: 65

Michaluk 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michaluk 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Michaluk, Dorota 2010. Białoruska Republika Ludowa 1918–1920. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UMK.

).

).Identity

Jerzy Chmielewski, editor of the journal of the Belarusian national minority, writing in Belarusian, described his countrymen as "Bielarus-Jaćviahi" and its southern neighbours as "Chachły" ("not connected with Ukrainians" - Chmielewski 2010 Chmielewski 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Chmielewski 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Chmielewski, Jerzy 2010. „Maja kraina prostaj movy”, Czasopis.pl. [http://czasopis.pl/ostrow-krynki/moj-widnokrag/blog]

).

). The ethnic identity of speakers of eastern Slavic varieties in Bialystok remains a matter of debate. In emerging media publications, Ukrainian or Belarusian ethnicity is often attributed to them (Kruk 1997: 65-66

Kruk 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kruk 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Kruk, Mikołaj 1997. „Białorutenika w białostockich czasopismach i periodykach w latach 1985-1995”, w: Jan F. Nosowicz (red.) Dziedzictwo przeszłości związków językowych, literackich i kulturowych polsko-bałto-wschodniosłowiańskich. Białystok: UwB, s. 63-72.

).

). In the early 1980s, every fourth inhabitant of Bialystok described himself as Belarusian, 30% felt the Poles, 30% described themselves as "Russians" (Mironowicz 2010: 23

Mironowicz 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mironowicz 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Mironowicz, Eugeniusz 2010. „Białorusini w Polsce (1919-2009)”, w: Teresa Zaniewska (red.) Białorusini. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, s. 9-28.

). According to the population census of 2000, Belarusians make up between 25 to 30% of the Orthodox community in Podlaskie (Podlasie North). About 1.5% identified themselves as Orthodox Ukrainians. The other Orthodox declared themselves Poles (Mironowicz 2010: 27

). According to the population census of 2000, Belarusians make up between 25 to 30% of the Orthodox community in Podlaskie (Podlasie North). About 1.5% identified themselves as Orthodox Ukrainians. The other Orthodox declared themselves Poles (Mironowicz 2010: 27 Mironowicz 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mironowicz 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Mironowicz, Eugeniusz 2010. „Białorusini w Polsce (1919-2009)”, w: Teresa Zaniewska (red.) Białorusini. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, s. 9-28.

).

).Konstatin Michalczuk has described the residents of the former province of Siedlce and Lublin as Ruthenians or Małorusy. This term is associated with the profession of Orthodox and Uniate Christianity (Łesiów 1994: 120-121

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiów 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Łesiów, Michał 1994. „Gwary ukraińskie między Bugiem i Narwią”, Białostocki Przegląd Kresowy II: 117-137.

na podstawie profilu białoruskiego.

).

). Borciuch and Olejnik (2001: 77

Borciuch i Olejnik 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Borciuch i Olejnik 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Borciuch, Maria & Marek Olejnik 2001. „Paralele leksykalne w gwarach ukraińskich i polskich gminy Dubicze Cerkiewne”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Hryhorij Arkuszyn (red.) Ukraińskie i polskie gwary pogranicza. Lublin-Łuck: Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze, s. 77-81.

) write:

) write: The Orthodox inhabitants of Bialystok in Poland for many years were called Belarusians. Meanwhile, the issue of ethnicity is not so simple. The Orthodox community in the region form two groups of different origins.For users of language varieties described here belong (or are) Polish-Lithuanian Tatars. Sources indicate that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most of the Tatars did not know the Tatar language (Antonowicz 1968: 256-257

The first is the Belarusians, the descendants of the ancient tribes of Krywicz and Drehowicz, living to the north of Narew and Narewka and to the east of Knyszyński Forest. The second is that of the residents of areas south of the Narew River and to the south and west of the Bialowieza Forest, the population derived from Volyn, or the ancestors [sic] of today's Ukrainians.

Antonowicz 1968 / komentarz/comment/r /

Antonowicz 1968 / komentarz/comment/r / Антонович А. К. [Antonowicz] 1968. „Краткий обзор белорусских текстов, писанных арабским письмом”, w: В. В. Мартынов, Н. И. Толстой (red.) Полесье (Лингвистика. Археология. Топонимика). Москва: Наука, s. 256-299.

). In Kostomłoty (a village in the province of Lublin) is the only Polish neo-Uniate parish (Byzantine Catholic Church), whose inhabitants speak, as they say, ‘chachłacki’ (Arkuszyn 2010: 140

). In Kostomłoty (a village in the province of Lublin) is the only Polish neo-Uniate parish (Byzantine Catholic Church), whose inhabitants speak, as they say, ‘chachłacki’ (Arkuszyn 2010: 140 Arkuszyn 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Arkuszyn 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Аркушин, Григорій [Arkuszyn] 2010. „Жителі Підляшшя про свою мову”, w: Dagmara Nowacka i in. (red.) Z lubelskich badań nad słowiańszczyzną wschodnią. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL, s. 137-149.

).

).In the 1970s Vladimir Pawluczuk wrote that the Bialystok region, regardless of the variety used, the population identified with "their own", i.e. Orthodox. Any awareness of Belarusianness was only a consciousness of the name and occurred in people with a certain level of education (Pawluczuk 1972: 131

Pawluczuk 1972 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pawluczuk 1972 / komentarz/comment/r / Pawluczuk, Włodzimierz 1972. Światopogląd jednostki w warunkach rozpadu społeczności tradycyjnej. Warszawa: PWN.

).

).Sajewicz insisted that the Orthodox dwellers were recognized in 1939 by the Soviet authorities as Belarusians - until then they were considered as "local" or "Russians". Today parts of the population, mostly educated, turn towards a sense of Polish, Belarusian or Ukrainian national consciousness (Sajewicz 1997: 94

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). Nationality "the local", "local", "Ruthenian" or "Orthodox" and "local language" were often declared also in pre-war Polesie. In 1931 as many as 63% of the region of Polesie established their language as ‘local speech’ (Wysocki 2005: 120

). Nationality "the local", "local", "Ruthenian" or "Orthodox" and "local language" were often declared also in pre-war Polesie. In 1931 as many as 63% of the region of Polesie established their language as ‘local speech’ (Wysocki 2005: 120 Wysocki 2005 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wysocki 2005 / komentarz/comment/r / Wysocki, Aleksander 2005. „Zarys problemu świadomości narodowej rdzennych mieszkańców województwa poleskiego w świetle dokumentów Centralnego Archiwum Wojskowego”, Biuletyn Wojskowej Służby Archiwalnej 27: 120-135.

). The term “Poleszucy” is seldom used by local inhabitants (Wysocki 2005: 122

). The term “Poleszucy” is seldom used by local inhabitants (Wysocki 2005: 122 Wysocki 2005 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wysocki 2005 / komentarz/comment/r / Wysocki, Aleksander 2005. „Zarys problemu świadomości narodowej rdzennych mieszkańców województwa poleskiego w świetle dokumentów Centralnego Archiwum Wojskowego”, Biuletyn Wojskowej Służby Archiwalnej 27: 120-135.

).

).Primarily activists of the Belarusian Social-Cultural Association, as well as a young intelligentsia, consider themselves Belarusian. The growth of Belarusian identity has contributed to cultural activities, as well as political. The first post-war Poland minority party existed from 1990-2005 as the Belarusian Democratic Union (Sajewicz 1997: 95

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). Local activists of Belarusian organizations are willing to include the entire population of Belarusian Orthodox in Bialystok (Sajewicz 1997: 94

). Local activists of Belarusian organizations are willing to include the entire population of Belarusian Orthodox in Bialystok (Sajewicz 1997: 94 Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). On the other hand, Ukrainian activists as Ukrainians are willing to consider all speakers of language varieties with Ukrainian characteristics.

). On the other hand, Ukrainian activists as Ukrainians are willing to consider all speakers of language varieties with Ukrainian characteristics. A growth in Ukrainian national consciousness among some Orthodox inhabitants of Bialystok has had an impact on those people noticing similarities of their own speech with standard Ukrainian language, and cultural relations. On the other hand, using the label of Ukrainian is subject to a certain reluctance because of the negative connotations of the times of activity of the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) in south-eastern Poland.

The rural population is not divided in the Bialystok area between the Belarusian- and Ukrainian-speaking, but it is aware of some differences of language. Speakers and their dialects are called Dziekały or Cieprucy, while the population in which the absence of the processes of palatalization is called determined Dekały and Podlasz (Padl'aš), the semantics of these names are often much more subtle and need not be limited only to the language issue. Another division used distinguishes between the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Lithuanian), and the Crown (Korolowcy) (Sajewicz 1997: 96-97

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sajewicz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Sajewicz, Michał 1997. „O białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej na Białostocczyźnie”, w: Feliks Czyżewski & Michał Łesiów (red.) Ze studiów nad gwarami wschodniosłowiańskimi w Polsce. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS, s. 91-107.

). The breakdown on Dekały and Dziekały, as well as language called korolowski (королjоуски) was already described in 1858 (Łesiw 1997: 282

). The breakdown on Dekały and Dziekały, as well as language called korolowski (королjоуски) was already described in 1858 (Łesiw 1997: 282 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

).

). In the Lublin region Ukrainians are considered to have been dealt with "Operation Vistula", or to come from beyond the river Bug, regardless of the language they use or their religion (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XX

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

). Ukrainians are contrasted with "the locals", who have never left their home areas.

). Ukrainians are contrasted with "the locals", who have never left their home areas.ISO Code

no code

in 2011, Jan Maksymiuk applied for a ISO 639-3 code for the Podlachian languages - the application was rejected (SIL 2011 SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

).

).

The Ethnologue refers to transitional Belarusian-Ukrainian dialects (Lewis 2009 Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).

UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger mentions Polesian as a vulnerable language.

The Linguascale encodes all Belarusian-Ukrainian transitional and Polesian varieties with: 53-AAA-edd.

in 2011, Jan Maksymiuk applied for a ISO 639-3 code for the Podlachian languages - the application was rejected (SIL 2011

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

SIL 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / SIL 2011. Change request documentation for: 2011-013. [http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/chg_detail.asp?id=2011-013&lang=pdl]

).

). The Ethnologue refers to transitional Belarusian-Ukrainian dialects (Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger mentions Polesian as a vulnerable language.

The Linguascale encodes all Belarusian-Ukrainian transitional and Polesian varieties with: 53-AAA-edd.

- Hawryluk 1988

- SIL 2011

- Lewis 2009

- Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998

- Łesiw 1997

- Wysocki 2005

- Głuszkowska 2001

- Sajewicz 1997

- Duliczenko 2002

- Pazdniakou 2007

- Krywicki 2003

- Hawryluk [?]

- Łesiów 1994

- Maksimiuk 2009

- Michaluk 2010

- Chmielewski 2010

- Kruk 1997

- Mironowicz 2010

- Borciuch i Olejnik 2001

- Antonowicz 1968

- Arkuszyn 2010

- Pawluczuk 1972

- Małecki 2004

- Warchoł 1992

- Smułkowa 2002

- Fionik i Wrubl'ewski 2006

- Tołstoj 1968

- Łapicz 1986

- Klimczuk 2010

- Fałowski 2011

- Fionikowie 2008

- Hlebowicz 2008

- Warchał 1992

- Leończuk 2008

- Stachwiuk 2006

- Kondratiuk 1972

- Sawicka i Wróblewski 1972

- Fionik 2011

- Wiarenicz 2009

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- I.Ignatiuk "Ukraińskie gwary południowego Podlasia

- M.Sarnac'ka - "Pukłunysja swujuj zymli"

- Tablice turystyczne po podlasku i po polsku

- Województwo poleskie w II Rzeczypospolitej

- Mapa Polesia

- Odmiany podlaskie i poleskie

- Gwary zachodniopoleskie na Białorusi

- Przykład ortografii w czasopiśmie Bielski Hostineć

- Użycie alfabetu łacińskiego w ortografii

- Tekst wschodniosłowiański pismem arabskim

- Banner pochodzący z 'Howorymo po swojomu'

- Banner pochodzący z 'Howorymo po swojomu'

- Strona tytułowa podlaskich czytanek dla dzieci

- Tablica w podlaskiej odmianie językowej

- Okładka płyty Піесні спуд Jанова.

- Przejściowe dialekty polsko-białorusko-ukraińskie

- Izoglosy białorusko-ukraińskiej granicy językowej

- Schematyczna granica językowa białorusko-ukraińska