dialect of Old Believers in Masuria

Masurian Old Believers – historical and cultural information

The Old Believer parish, which to this day exists in the Masuria region of Poland, was established in the 1830s. The Masurian Old Believers were Russian refugees looking for a new place to settle due to the persecutions their religion suffered in Russia. Andreas Kossert (2001: 174 Kossert 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kossert 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Kossert, Andreas 2001. Preußen, Deutsche oder Polen? Die Masuren im Spannungsfeld des ethnischen Nationalismus 1870-1956. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

) calls them the last link in the long chain of religious refugees, after such groups as Huguenots, Calvinists, and Protestants, who arrived in Prussia, while Eugeniusz Iwanc (1977: 34

) calls them the last link in the long chain of religious refugees, after such groups as Huguenots, Calvinists, and Protestants, who arrived in Prussia, while Eugeniusz Iwanc (1977: 34 Iwaniec 1977 / komentarz/comment/r /

Iwaniec 1977 / komentarz/comment/r / Iwaniec, Eugeniusz 1977. Z dziejów staroobrzędowców na ziemiach polskich XVII-XX w. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

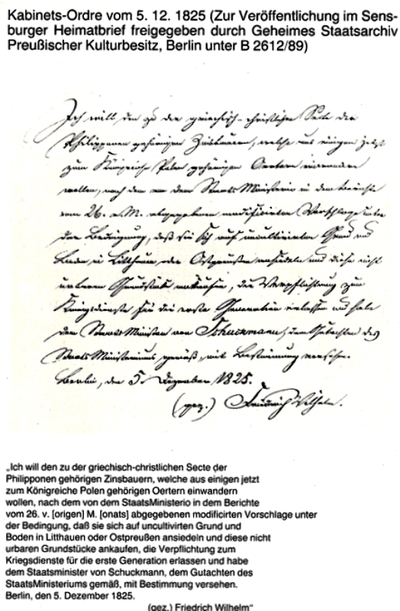

) even compares them to Jews, scattered all around the world. The Old Believers from the religious communities in north-eastern Poland asked king Frederick William of Prussia for permission to settle in what was then a religiously liberal Eastern Prussia. The king issued a regulation on 5th December, 1825, where he allowed the religious refugees to purchase the uninhabited Masurian woodlands around the lake Bełdany and the river Krutyń. Iryda Grek-Pabisowa (1999: 56

) even compares them to Jews, scattered all around the world. The Old Believers from the religious communities in north-eastern Poland asked king Frederick William of Prussia for permission to settle in what was then a religiously liberal Eastern Prussia. The king issued a regulation on 5th December, 1825, where he allowed the religious refugees to purchase the uninhabited Masurian woodlands around the lake Bełdany and the river Krutyń. Iryda Grek-Pabisowa (1999: 56 Grek-Pabisowa 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Grek-Pabisowa 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Grek-Pabisowa, Iryda 1999. Staroobrzędowcy. Szkice z historii, języka, obyczajów, wybór prac z okazji 45-lecia pracy naukowej. Warszawa: Slawistyczny Ośrodek Wydawniczy, Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk.

) remarks that the regulation was beneficial to both sides: “The Old Believers settled in sparsely populated areas, depopulated by epidemics and the Napoleonic war (the population had decreased by 14% at that time) (...) While to the Old Believers, settling in the Pisz Forest meant quiet life and the possibility of uninterrupted religious practice.”

) remarks that the regulation was beneficial to both sides: “The Old Believers settled in sparsely populated areas, depopulated by epidemics and the Napoleonic war (the population had decreased by 14% at that time) (...) While to the Old Believers, settling in the Pisz Forest meant quiet life and the possibility of uninterrupted religious practice.”

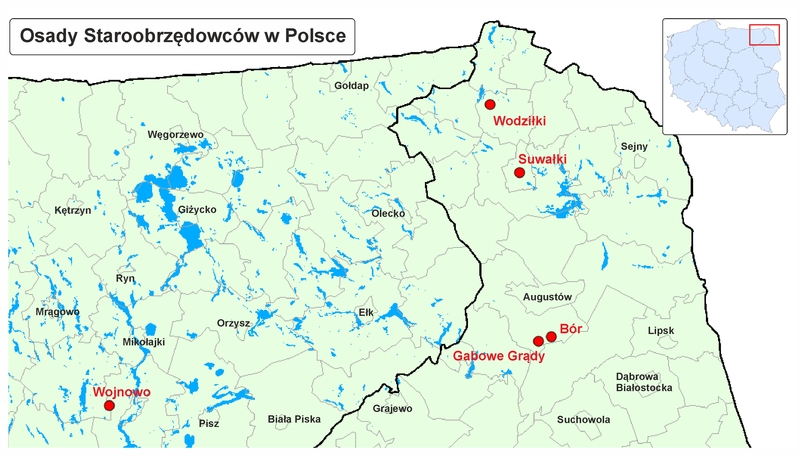

Old Believers' settlements in Poland - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz.

The photograph shows a copy of king Frederick William of Prussia’s regulation, in which he agreed to the settlement of the Old Believers in Masuria. The copy of the manuscript, together with the transcription, was published in Rolf W. Krause’s article in the periodical Sensburger Heimatbrief, No. 35 (1990: 48

Sensburger Heimatbrief 1990 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sensburger Heimatbrief 1990 / komentarz/comment/r / Sensburger Heimatbrief 1990, 35: 47-57. Remscheid: Bergische Druckerei und Verlag Ludwig Koch GmbH & Co.

), with the consent of the National Secret Archive, to celebrate the 160th anniversaty of the Old Believers’ arrival in Eastern Prussia.

), with the consent of the National Secret Archive, to celebrate the 160th anniversaty of the Old Believers’ arrival in Eastern Prussia.The first Old Believer, Onufry Jakowlew, arrived in 1826 from the Augustów-Suwałki centre and founded an eponymous village, Onufryjewo, which still exists today. With time, more Old Believers moved in to Eastern Prussia and populated more villages, such as Wojnowo, where there is a cloister by the lake Duś.

The Old Believer cloister in Wojnowo by the lake Duś, viewed from the graveyard. Photo: A. Jorroch.

There are also two Old Believer graveyards in Wojnowo, and a molenna – a temple, where the Old Believers to this day say Sunday mass and hold holiday and burial services.

Old Believers’ graveyard gate in Wojnowo. Photo: A. Jorroch.

In later years Old Believers founded more villages near the river Krutyń: Gałkowo, Iwanowo, Śwignajno, Kadzidłowo, Osiniak, Piotrowo, Modliszki, Zameczek, and Piaski by the lake Bełdany.

An Old Believer wooden house in Wojnowo. Photo: A. Jorroch.

Having settled down in Masuria, Old Believers found themselves surrounded by German language and culture, since until the end of the Second World War this region was the southern part of Eastern Prussia. For nearly 200 years Masurian Old Believers have been a part of both the region’s social life and their own community’s religious life. Researchers have been indicating the distinctness of Old Believers, who, focused on their parish life, avoided contact with their surroundings (Iwaniec 1977: 224 ff

Iwaniec 1977 / komentarz/comment/r /

Iwaniec 1977 / komentarz/comment/r / Iwaniec, Eugeniusz 1977. Z dziejów staroobrzędowców na ziemiach polskich XVII-XX w. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

). They did not eat from the same dishes as people of different faiths, and did not form mixed marriages until the 20th century, while other Masurians had been marrying people of different nationalities and religions much earlier (Grek-Pabisowa 1999: 285

). They did not eat from the same dishes as people of different faiths, and did not form mixed marriages until the 20th century, while other Masurians had been marrying people of different nationalities and religions much earlier (Grek-Pabisowa 1999: 285 Grek-Pabisowa 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Grek-Pabisowa 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Grek-Pabisowa, Iryda 1999. Staroobrzędowcy. Szkice z historii, języka, obyczajów, wybór prac z okazji 45-lecia pracy naukowej. Warszawa: Slawistyczny Ośrodek Wydawniczy, Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk.

). Masurian Old Believers gradually integrated with the surrounding German culture (as described by Anna Zielińska 1999: 103

). Masurian Old Believers gradually integrated with the surrounding German culture (as described by Anna Zielińska 1999: 103 Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Zielińska, Anna 1999. „Staroobrzędowcy w Hamburgu. Studium złożonej tożsamości”, Etnografia Polska 43:1/2: 101-120.

). In the conversation fragment below, a Masurian Old Believer woman talks about friendships and mixed marriages between Old Believers and Protestants:

). In the conversation fragment below, a Masurian Old Believer woman talks about friendships and mixed marriages between Old Believers and Protestants:Hattet ihr auch evangelische Freunde?

Eng: Did you also have Protestant friends?

Wi ham auch geheiratet. Wi ham auch viel geheiratet. So ein Mischmasch war das.

We married a lot. We also married a lot. It was a sort of mish-mash.

Kanntest du irgendwelche Leute, die so geheiratet haben?

Did you know any people who married like that?

Ja, ich hatte selbst ein Freund, de war ewangelisch.

Yes, I myself had a friend who was a Protestant.

Wie hieß er?

What was his name?

Derwisch hieß e abe de is inzwischen gestorben. De war älter als ich, de war vielleich na zehn Jahre älter.

His name was Derwisz, but he’s dead now. He was older than me, perhaps ten years older.

The photograph presents a part of a traditional wooden house belonging to an Old Believer family in Wojnowo, which was rebuilt in the 1960s. The rest of the house was demolished and a modern brick house was built in its place, but the old half of the family house can still be seen from the street. Photo: A Jorroch.

The assimilation of the German culture can also be seen in some adopted customs and traditions. This phenomenon concerns both the sacral and lay spheres of life. Before the Easter meal, Masurian Old Believers – especially if there are children in the family – would play by the festive table, hitting each other’s dyed eggs until one breaks; the person who finished with an unbroken egg, wins. Then everybody eats the eggs during the meal. This custom is known as ‘Eierpecken’ and is one of many Easter games popular also in Germany and Austria (www.brauchtumsseiten.de/a-z/e/eierpecken/home.html) . A similar custom is also known in the East of Poland among non-Old Believer families, as a game played after the Easter breakfast. In that case, the broken eggs are to be eaten over the course of the following days.

Keeping in mind tourists visiting the cloister, a bilingual, Polish-German information board has been erected in Wojnowo. Photo: A. Jorroch.

Eastern Prussian cultural influence can also be seen in sacral architecture. The exterior of the Masurian Old Believer molenna in Wojnowo, built in the 1920s, is different from the temples in other religious centres in north-eastern Poland. The red brick Gothic building resembles Protestant churches from the Masuria region.

Old Believer molenna in Wojnowo. Photo: A. Jorroch.

A summer kitchen in the yard of a house in Piaski. Photo: A. Jorroch

Old Believers, much like other Masurians, have “summer kitchens” (Ger. ‘Sommerküche’ or ‘Waschküche’) in their farmyards, outside the houses. Summer kitchens were used for meat processing, fish gutting, baking and cooking, as well as making fodder for animals. The preparation of meals outside the house kitchen helped to keep the house clean and free of bad smells. It was particularly practical in the summer, when on hot days meals had to be cooked in traditional wood-burning stoves, which would make an indoor kitchen extremely hot. Today, summer kitchens are no longer useful, since people have switched to gas or electric cookers.

Another factor contributing to the adoption of the German culture by Masurian Old Believers were administration regulations, which applied to the whole population of Eastern Prussia. Such regulations included, e.g. the introduction of compulsory schooling for children in 1847, or the obligatory military service for men. Military service meant for the Old Believers a departure from the tenets of their faith, as they were required to take active part in military conflicts. It was also one of the reasons for their emigration (Iwaniec 1977: 108

Iwaniec 1977 / komentarz/comment/r /

Iwaniec 1977 / komentarz/comment/r / Iwaniec, Eugeniusz 1977. Z dziejów staroobrzędowców na ziemiach polskich XVII-XX w. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

). Old Believers bore witness to many political changes in Masuria. Towards the end of the Second World War, Old Believers saw and fell victims of some dramatic events, when Red Army soldiers brutally robbed, murdered and attacked the local population. Eye witnesses, who were children at the time, mention rapes and kidnappings of women, fear, hiding in the forest, and murders on their fellow believers, who were treated just as brutally by the soldiers as the rest of Masurians. Those tragic events have been described in literature (Zielińska 1999: 104 ff

). Old Believers bore witness to many political changes in Masuria. Towards the end of the Second World War, Old Believers saw and fell victims of some dramatic events, when Red Army soldiers brutally robbed, murdered and attacked the local population. Eye witnesses, who were children at the time, mention rapes and kidnappings of women, fear, hiding in the forest, and murders on their fellow believers, who were treated just as brutally by the soldiers as the rest of Masurians. Those tragic events have been described in literature (Zielińska 1999: 104 ff Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Zielińska, Anna 1999. „Staroobrzędowcy w Hamburgu. Studium złożonej tożsamości”, Etnografia Polska 43:1/2: 101-120.

). After the country borders changed in 1945, the religious community of Masurian Old Believers found itself within the borders of the Polish Republic, which entailed great changes in the lives of its members. The Masurian Old Believers had lived with German as the official language of state administration and those of them who were born in Masuria had to learn Polish. Only those who had formerly lived in north-eastern Poland, that is in one of the other religious centres, spoke fluent Polish, which was the language of administration in that region. (The bilingualism of the Suwałki-Augustów region Old Believers has been described by Michał Głuszkowski 2011: 76 ff

). After the country borders changed in 1945, the religious community of Masurian Old Believers found itself within the borders of the Polish Republic, which entailed great changes in the lives of its members. The Masurian Old Believers had lived with German as the official language of state administration and those of them who were born in Masuria had to learn Polish. Only those who had formerly lived in north-eastern Poland, that is in one of the other religious centres, spoke fluent Polish, which was the language of administration in that region. (The bilingualism of the Suwałki-Augustów region Old Believers has been described by Michał Głuszkowski 2011: 76 ff Głuszkowski 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Głuszkowski 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Głuszkowski, Michał 2011. Socjologiczne i psychologiczne uwarunkowania dwujęzyczności staroobrzędowców regionu suwalsko-augustowskiego. Toruń: Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika.

). Members of the Masurian parish who were born in the period when Masuria was part of Germany were not in contact with the Masurian dialect. They had to learn Polish, which many Old Believers still living in Masuria testify. Below is a fragment of a statement by a Masurian Old Believer woman from Gałkowo, from 2008:

). Members of the Masurian parish who were born in the period when Masuria was part of Germany were not in contact with the Masurian dialect. They had to learn Polish, which many Old Believers still living in Masuria testify. Below is a fragment of a statement by a Masurian Old Believer woman from Gałkowo, from 2008:Wi lernen bischen Polnisch, nich. Ich kӧnnte auch nich perfekt mit einem Pol… Ihr gingt, ihr wart in de polnischen Schule, habt das Polnische gelernt, nich. Wir hatten das nich. Wir hatten das nicht gehabt, nicht. So jetzt in de Nachkriegszeit, nich. Is das, mein Gott, ihr seid schon Gelehrte!

('We learn a bit of Polish, no. I also couldn’t perfectly with a Pol... You went, you were in a Polish school, you’ve learnt Polish, no. We hadn’t that. We hadn’t had that, no. So now after the war, no. That is, my God, you’re already learned!')

Since the annexation of Masuria by Poland, there has been on the one hand an emigration of a large part of the inhabitants to Germany and on the other hand an influx of new population into this region. New settlers came from different parts of Poland, most of them from the nearby region of Kurpie. Both Masurians and Old Believers who did not know Polish met obstacles in their everyday lives, being unable to communicate in offices, schools, shops, and with their new neighbours in the streets. For the Masurian Old Believers who already knew Russian and German, the new reality meant the necessity of learning a third language, Polish. Therefore, the generation born by the end of 1950s is multilingual. They speak fluent German, which they picked up as children, from their parents at home etc. They also know Russian, the language of their ancestors, and the Old Believers’ dialect of Russian. In day-to-day life they speak Polish or the Masurian dialect .

Masurian Old Believers do not identify clearly with one nationality, Zielińska says (1999: 103 ff

Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Zielińska, Anna 1999. „Staroobrzędowcy w Hamburgu. Studium złożonej tożsamości”, Etnografia Polska 43:1/2: 101-120.

). Their attachment to Polish, Russian, or German culture depends on many factors, such as: environment, age, life experience, and economic reasons. In the interviews conducted by Katarzyna Krasowska, an Old Believer from Wojnowo who conducted research on the identity of the Old Believers from her parish, the interviewees did not provide a clear national identity. They said they had been born in Germany, they were living in Poland, their ancestors had come from Russia, and they themselves were of “the Russian creed” (Krasowska 2003: 60

). Their attachment to Polish, Russian, or German culture depends on many factors, such as: environment, age, life experience, and economic reasons. In the interviews conducted by Katarzyna Krasowska, an Old Believer from Wojnowo who conducted research on the identity of the Old Believers from her parish, the interviewees did not provide a clear national identity. They said they had been born in Germany, they were living in Poland, their ancestors had come from Russia, and they themselves were of “the Russian creed” (Krasowska 2003: 60 Krasowska 2003 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krasowska 2003 / komentarz/comment/r / Krasowska, Katarzyna 2003. Tożsamość Filipona, relikt przeszłości czy tradycja żywa? - Studium na podstawie badań przeprowadzonych we wsi mazurskiej Wojnowo [niepublikowana praca magisterska napisana pod opieką dr Wojciecha Łukowskiego]. Warszawa: Uniwersytet Warszawski, Instytut Politologii.

). Zielińska (1999: 118 ff

). Zielińska (1999: 118 ff Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zielińska 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Zielińska, Anna 1999. „Staroobrzędowcy w Hamburgu. Studium złożonej tożsamości”, Etnografia Polska 43:1/2: 101-120.

) draws a conclusion from the research on the complex identities of the Old Believers from Hamburg, a multi-cultural and multi-confessional city, stating that “the importance of religion diminishes in a situation of pluralism, cultural compromise, and tolerance.” The same mechanism seems to be at work in Masuria today, where Masurian Old Believers appear to adopt elements of the surrounding Polish culture. Just as they integrated with the local population in Masuria, when it was still part of Germany, today’s Old Believers do not avoid close contact with their neighbours, regardless of what faith they are and where they may come from. It manifests itself in the exchange of holiday wishes and even in spending holidays together. Catholic and Protestant friends and acquaintances attend Old Believer funerals, and even help organise wakes. Neighbours help one another with construction works, farming, gardening, and house cleaning. Women from nearby villages come to sort potatoes together or help with meat processing. Pieces of cooking advice are exchanged, as are fruits and vegetables collected in the summer in gardens. Catholic customs also inform Old Believer culture: candles are lit on graves in Old Believer graveyards, just like in Catholic ones. (Artur Szmigiel mentions that in his 2004 spring impressions on the website www.philipponia.republika.pl). Interpersonal relations in Masuria are religiously tolerant and respectful towards past experiences, family histories, and local people’s customs and traditions. Anna Zielińska’s conclusion, drawn based on the Hamburg experience, seems to hold true in today’s Polish Masuria, where the state no longer forces a nationally and religiously monolithic image of the country. The freedom of choice of identity and confession is conducive, therefore, to a country’s cultural wealth.

) draws a conclusion from the research on the complex identities of the Old Believers from Hamburg, a multi-cultural and multi-confessional city, stating that “the importance of religion diminishes in a situation of pluralism, cultural compromise, and tolerance.” The same mechanism seems to be at work in Masuria today, where Masurian Old Believers appear to adopt elements of the surrounding Polish culture. Just as they integrated with the local population in Masuria, when it was still part of Germany, today’s Old Believers do not avoid close contact with their neighbours, regardless of what faith they are and where they may come from. It manifests itself in the exchange of holiday wishes and even in spending holidays together. Catholic and Protestant friends and acquaintances attend Old Believer funerals, and even help organise wakes. Neighbours help one another with construction works, farming, gardening, and house cleaning. Women from nearby villages come to sort potatoes together or help with meat processing. Pieces of cooking advice are exchanged, as are fruits and vegetables collected in the summer in gardens. Catholic customs also inform Old Believer culture: candles are lit on graves in Old Believer graveyards, just like in Catholic ones. (Artur Szmigiel mentions that in his 2004 spring impressions on the website www.philipponia.republika.pl). Interpersonal relations in Masuria are religiously tolerant and respectful towards past experiences, family histories, and local people’s customs and traditions. Anna Zielińska’s conclusion, drawn based on the Hamburg experience, seems to hold true in today’s Polish Masuria, where the state no longer forces a nationally and religiously monolithic image of the country. The freedom of choice of identity and confession is conducive, therefore, to a country’s cultural wealth.ISO Code

Language varieties of the Old-Bielievers have no separate code, see: Russian of Old Believers

- przyp01

- przyp02

- Peskow 1994

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- Madajczyk 2000

- przyp12

- przyp13

- Falińska 1994

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- przyp24

- przyp25

- przyp26

- przyp27

- przyp28

- przyp29

- przyp30

- Fularczyk 2009

- przyp31

- Mitzka 1959

- przyp32

- przyp33

- przyp34

- przyp35

- przyp36

- Księżyk 2008

- przyp37

- przyp38

- przyp39

- przyp40

- przyp41

- przyp42

- przyp43

- przyp44

- Thomason 2001

- przyp45

- przyp46

- przyp47

- przyp48

- przyp49

- przyp50

- przyp51

- przyp52

- przyp53

- Hauptmann 2005

- przyp54

- Mirowicz i Dulewicz 1970

- przyp55

- przyp56

- przyp57

- przyp58

- przyp59

- przyp60

- Kossert 2001

- Iwaniec 1977

- Grek-Pabisowa 1999

- Sensburger Heimatbrief 1990

- Zielińska 1999

- Głuszkowski 2011

- Krasowska 2003

- Szulc 1991

- Göttert 2011

- Łopuszańska-Kryszczuk 2013

- Weinreich 1977

- Zielińska 1996

- Dzięgiel 2009

- Ziółkowska 2010

- fragment nabożeństwa w molennie w Wojnowie

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- zarzadzenie Fryderyka Wilhelma

- Klasztor w Wojnowie

- wejście na cmentarz w Wojnowie

- Dom w Wojnowie

- Tradycyjny dom drewniany

- Tablica informacyjna w Wojnowie

- Molenna w Wojnowie

- Kuchnia letnia

- Pascha wielkanocna

- Krzyż Krassowskiego.

- mapa miejscowości mazurskich Staroobrzędowców

- księga liturgiczna Staroobrzędowców z Wojnowa

- Mapa okolic Wojnowa

- Tablica na cmentarzu w Suwałkach

- Molenna na cmentarzu w Suwałkach