Low German

The Name

Endonyms

Plattdüütsch is the endonym which describes Low German in the Pomeranian dialect. There were also names for respective varieties, e.g. Pomeranian was called Platt Pamersch (Platt ‘Pomeranian’) or Pahmerische Buhr-Sprake (Pomeranian language of peasants) (Adam 1893: 124, 128 Adam 1893 / komentarz/comment/r /

Adam 1893 / komentarz/comment/r / Adam, Karl 1893. „Niederdeutsche Hochzeitsgedichte des 17. und 18. Jahrh aus Pommern”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XIX: 122-130.

), and Danzig dialect Danzjer Platt (Pinnow 2006b: 14

), and Danzig dialect Danzjer Platt (Pinnow 2006b: 14 Pinnow 2006b / komentarz/comment/r /

Pinnow 2006b / komentarz/comment/r / Pinnow, Jürgen (red.) 2006b. So lachte man in Danzig. München: Lincom Europa.

). In the north of Germany, the word Platt means local variety of language (dialect).

). In the north of Germany, the word Platt means local variety of language (dialect).Exonyms

In German (and specifically High German, Ger. Hochdeutsh), which is predominantly the basis for the standard language on the area of the usage of Low German dialects, Low German is called Plattdeutsch, or alternatively, Niederdeutsch.In English, the name Low German or Low Saxon is used.

The Ethnologue, issued in English, uses the following names for Low German (without the distinction between endonyms and exonyms): Low Saxon, Low German, Nedderdütsch, Neddersassisch, Nedersaksisch, Niedersaechsisch, and Plattdüütsch.

History and geopolitics

Location in the Republic of Poland

In The First Republic of Poland, Low German dialects were used primarily in the area of Royal Prussia and the following fiefdoms of the Republic: the Duchy of Prussia, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, as well as Lauenburg and Bütow Land. In the Second Republic, Low German dialects were used in Pomerelia.

Illustration: Germanic language variations in the area of the present northern Poland at the beginning of the 20th century (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, prepared after: http://mitglied.multimania.de/pomerania2/hist_maps/survey/dialect2a.jpg).

and other lands of the former Prussian Partition (Poznań Voivodeship), but also occasionally e.g. in Dobrzyń Land (at that time Warsaw Voivodeship, presently Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship), where local dialect was researched by Gustaw Foss, in the Lublin Region and the Chełm Region (Sanders 1982: 64

Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Sanders, Willy 1982. Sachsensprache. Hansesprache. Plattdeutsch. Göttingen: Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht.

) – compare with the maps at http://www.many-roads.com/2011/02/06/deutsche-mundarten-german-language/.

) – compare with the maps at http://www.many-roads.com/2011/02/06/deutsche-mundarten-german-language/.

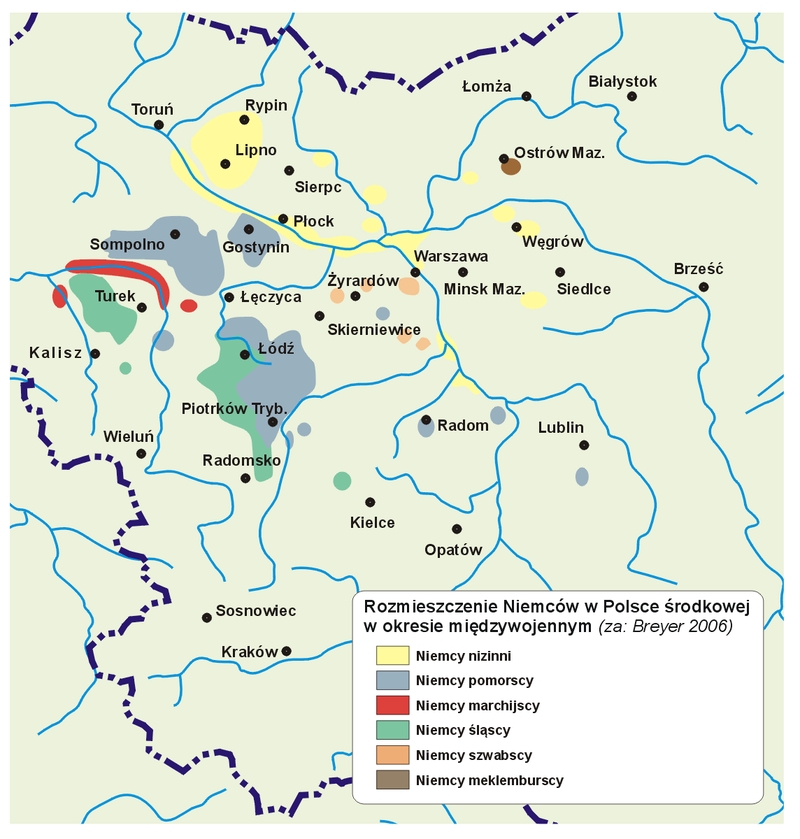

Illustration: Patterns of German settlement in central Poland during the interwar period (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Breyer 2006: 9

Breyer 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Breyer 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Breyer, Albert 2006. Deutsche Gaue in Mittelpolen. Seefeld: www.UsptreamVistula.org.

).

).

There is no data dealing with the situation of Low German dialects during the period of The People's Republic of Poland. In 1951, after several stages of expulsions had ended, only 364 German people (Słabig 2009

Słabig 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Słabig 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Słabig, Arkadiusz 2009. „Działania aparatu bezpieczeństwa wobec ludności niemieckiej w województwie szczecińskim w latach pięździesiątych XX w.”, w: Jarosław Syrnyk (red.) Aparat bezpieczeństwa Polski Ludowej wobec mniejszości narodowych i etnicznych oraz cuodzoziemców. Warszawa: IPN, s. 32-56.

) lived in Szczecin Voivodeship. However, the details concerning the linguistic situation among this population are not known. It is not known whether or how the new circumstances (the inflow of Polish people and transition to the role of a minority, socialism as a political system) influenced vocabulary at the very least, as it happened in the case of Ukrainian dialects of the same area (compare: Jarczak 1972: 50

) lived in Szczecin Voivodeship. However, the details concerning the linguistic situation among this population are not known. It is not known whether or how the new circumstances (the inflow of Polish people and transition to the role of a minority, socialism as a political system) influenced vocabulary at the very least, as it happened in the case of Ukrainian dialects of the same area (compare: Jarczak 1972: 50 Jarczak 1972 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jarczak 1972 / komentarz/comment/r / Jarczak, Danuta 1972. „Niektóre osobliwości przemieszczonej gwary ukraińskiej w powiecie stargardzkim województwa szczecińskiego”, Zeszyty Naukowe 6: 41-54. Szczecin: Uniwersytet Poznański im. Adama Mickiewicza. Wyższa Szkoła Nauczycielska w Szczecinie.

). In 1971, a monograph by G. Foss was published. It was dedicated to the Low German dialect of Dobrzyń land (Foss 1971

). In 1971, a monograph by G. Foss was published. It was dedicated to the Low German dialect of Dobrzyń land (Foss 1971 Foss 1971 / komentarz/comment/r /

Foss 1971 / komentarz/comment/r / Foss, Gustaw 1971. Die niederdeutsche Siedlungsmundart im Lipnoer Lande. Poznań: Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.

).

).

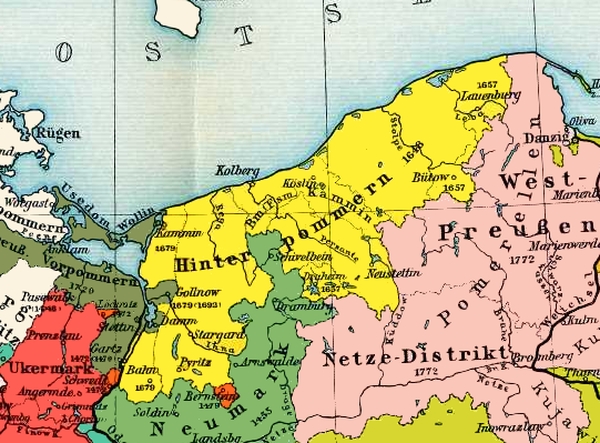

Illustration : Farther Pomerania and West Prussia (Putzger 1905

Putzger 1905 / komentarz/comment/r /

Putzger 1905 / komentarz/comment/r / Putzger, F. W. 1905. Historischer Schul-Atlas. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing.

, taken from: Wikimedia Commons)

, taken from: Wikimedia Commons)Presently in Poland, there are no areas inhabited by users of Low German dialects. According to Anna Zielińska (2012: 13

Zielińska 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zielińska 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Zielińska, Anna et al. 2012. „Wielojęzyczność w województwie lubuskim. Stan współczesny”, w: Beata A. Orłowska & Krzysztof Wasilewski (red.) Mniejszości regionu pogranicza polsko-niemieckiego. Gorzów Wielkopolski: Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa.

), a variety of Brandenburgisch dialect is spoken fluently by some of the inhabitants of Lubusz Voivodeship who were born before the war.

), a variety of Brandenburgisch dialect is spoken fluently by some of the inhabitants of Lubusz Voivodeship who were born before the war.When comparing the historical scope of Low German dialects with the present map of Poland, one can distinguish the following areas where Low German dialects were used:

- Pomerania (Ger. Pommern): the area of former Farther Pomerania (Hinterpommern) and the eastern border of West Pomerania (Vorpommern) with Szczecin (the area of, more or less, the present day West Pomeranian Voivodeship);

- Prussia with Pomerelia, except for the areas of High German dialects (the area of, more or less, Pomeranian and Warmian-Masurian Voivodeships);

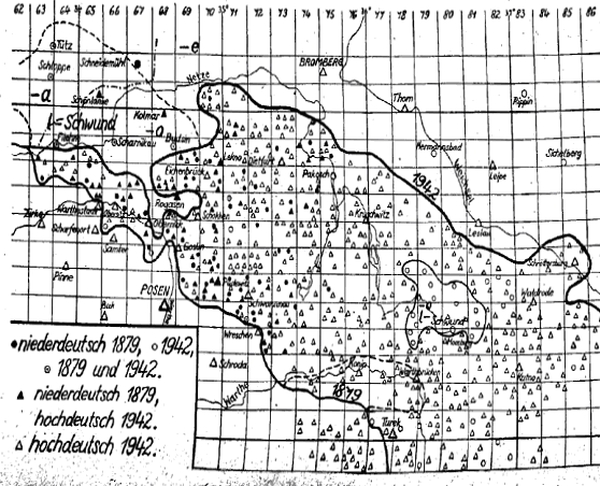

- The northern part of Posen province, or Wartheland (the name that was used by the authorities of the Third Reich, a part of the present day Greater Poland and Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeships) – the southern border of the areas of usage of Low German in Greater Poland between 1879 and 1942 moved systematically to the north and east, from the areas near Warta to Vistula and Noteć. These changes are discussed by Walther Mitzka (1954

Mitzka 1954 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1954 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka, Walther 1954. „Das Niederdeutsche im Wartheland”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 77: 111-119. ) in his article “Das Niederdeutsche im Wartheland”;

) in his article “Das Niederdeutsche im Wartheland”;

Illustration: Shift of the border of usage of High and Low German varieties in Poznań Voivodeship between 1879 and 1942 (after Mitzka 1954: 114

Mitzka 1954 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1954 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1954. „Das Niederdeutsche im Wartheland”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 77: 111-119.

)

)

Illustration: Posen province in 1849 (by Geographische Anstalt des Bibliographischen Instituts in Hildburghausen, Amsterdam, und New York (Meyer's Zeitungs-Atlas N. 40) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons).

- The New March (Neumark) – the area of Brandenburg to the east of Oder (today it is part of Lubusz Voivodeship).

Illustration: The New March (Müller-Baden 1905

Müller-Baden 1905 / komentarz/comment/r /

Müller-Baden 1905 / komentarz/comment/r / Müller-Baden, Emanuel 1905. Bibliothek allgemeinen und praktischen Wissens für Militäranwärter. T. 1. Berlin: Bong.

, after: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Provinz_Brandenburg_1905.png).

, after: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Provinz_Brandenburg_1905.png).Mennonites and Plautdietsch

The language of Mennonites, called Plautdietsch, originates from Prussia and is widespread in the world. In Plautdietsch language, the general term for Low German language (which includes other varieties as well) is nadadietsch (compare: Wiens 2009 Wiens 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiens 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiens, Peter 2009. „Fresch jewehlt: Bundesrot fe Nadadietsch”, Plautdietsch-Freunde e. V., [http://www.plautdietsch-freunde.de/fresch-jewehlt-bundesrot-fe-nadadietsch.html].

).

).Other locations

Descendants of Pomeranians who use the Pomeranian variety of Low German (Höhmann and Savedra 2011 Höhmann i Savedra 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Höhmann i Savedra 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Höhmann, Beate & Mônica M. G. Savedra 2011. „Das Pommerische in Espírito Santo: ergebnisse und perspektiven einer soziolinguistischen studie”, Pandaemonium Germanicum 18. [http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1982-88372011000200014&lng=en&nrm=iso]

) live in Brazil (e.g. Esprito Santo state) and the USA (Wisconsin state).

) live in Brazil (e.g. Esprito Santo state) and the USA (Wisconsin state).Low German (in its many varieties) is also used in Germany and the Netherlands (in these countries it is listed on the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages). According to The Ethnologue, 10 million Germans understand Low German, but there are many fewer native speakers.

History and origins

German people started to settle in Pomerania after 1178 – they came chiefly from Northern, and less frequently from Central Germany. The oldest source that describes a location of a German village (Baumgart – today Ogrodniki, Elbląg district) dates back to May 21, 1300 (Łopuszańska 2008b: 222 Łopuszańska 2008b / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008b / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008b. „Sprachlichkeit Danzigs”, w: Andrzej Kątny (red.) Kontakty językowe i kulturowe w Europie. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo UG.

; Jenks and Sarnowsky 2009

; Jenks and Sarnowsky 2009 Jenks i Sarnowsky 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jenks i Sarnowsky 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Jenks, Stuart & Jürgen Sarnowsky 2009. Das virtuelle Preußische Urkundenbuch. Regesten und Texte zur Geschichte Preußens und des Deutschen Ordens - Ältere Abteilung (1140-1381). [http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/Landesforschung/pub/orden1300.html]

).

).The presence and shape of Low German dialects in Pomerania were changed by migrations of settlers from Lower Saxony, Ostfalia and Westfalia, as well as later neighbourhood to the east with Prussian lands where Low German was used (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 180-181

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).In addition, the area between the Vistula and Nemen rivers was formerly inhabited by Baltic Prussians, and then colonized by the Teutonic Order (Ziesemer 1911: 129

Ziesemer 1911 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer 1911 / komentarz/comment/r / Ziesemer, Walther 1911. „Geistiges Leben im Deutschen Orden”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 71/73: 129-139.

). The Teutonic colonization began in 1226 in Orłowo village in Kujawy, and in Vogelsang castle (now situated in Toruń) which was located near the estuary of the River Drwęca , on the southern bank of the Vistula River. The castle was built for the Teutonic Knights by the Mazovian prince, Konrad Mazowiecki (Turnbull 2011: 7-8

). The Teutonic colonization began in 1226 in Orłowo village in Kujawy, and in Vogelsang castle (now situated in Toruń) which was located near the estuary of the River Drwęca , on the southern bank of the Vistula River. The castle was built for the Teutonic Knights by the Mazovian prince, Konrad Mazowiecki (Turnbull 2011: 7-8 Turnbull 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Turnbull 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Turnbull, Stephen 2011. Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (1). The red-brick castles of Prussia 1230-1466. Oxford: Osprey.

). The first colonisers, who originated from Thuringia, Saxony, and somewhat later from Silesia, did not speak Low German. Nonetheless, a strip of land at the coast near Elbląg, narrow at the beginning, was colonized by Low German speakers from near Lübeck (Schleswig-Holstein). Around mid-15th century, the major inflow of colonisers from the heart of Germany ceased (Siatkowski 1983: 111-112

). The first colonisers, who originated from Thuringia, Saxony, and somewhat later from Silesia, did not speak Low German. Nonetheless, a strip of land at the coast near Elbląg, narrow at the beginning, was colonized by Low German speakers from near Lübeck (Schleswig-Holstein). Around mid-15th century, the major inflow of colonisers from the heart of Germany ceased (Siatkowski 1983: 111-112 Siatkowski 1983 / komentarz/comment/r /

Siatkowski 1983 / komentarz/comment/r / Siatkowski, Janusz 1983. „Interferencje językowe na Warmii i Mazurach”, Studia z Filologii Polskiej i Słowiańskiej XXI: 103-115.

).

).The lands from where the colonisers originated, are not only the areas in present day Germany, but also in Holland. Walther Mitzka (1955: 67-82

Mitzka 1955 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1955 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1955. „Wortgeographie und Stammheimat niederdeutscher Ostsiedlung”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 78: 67-82.

) discussed the usage of loanwords from Dutch language on the area of present day Poland. Robert Holsten established a list of loanwords from Flemish that were used in the area of Oder River (Holsten 1947

) discussed the usage of loanwords from Dutch language on the area of present day Poland. Robert Holsten established a list of loanwords from Flemish that were used in the area of Oder River (Holsten 1947 Holsten 1947 / komentarz/comment/r /

Holsten 1947 / komentarz/comment/r / Holsten, Robert 1947. „Niederländische Fischerflurnamen im pommerschen Odergebiet”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung LXIX/LXX: 114-117.

).

).In the origin of dialects which are used in the land of Poland today, Slavic languages (Polish, Pomeranian) and Baltic languages (Prussian) had a minor impact as well. Because of that, one can observe Slavic influences in the language – both in Pomeranian dialects (e.g. Scharugg ‘an old horse’ from Slavic Pomeranian szaruga ‘a lame horse’) and in Prussian dialects (e.g. Schlietsch – ‘herring’) (Winter 1967

Winter 1967 / komentarz/comment/r /

Winter 1967 / komentarz/comment/r / Winter, Renate 1967. „Suffixe der slawischen Lehnwörter im Pommerschen und ihr Einfluß auf die niederdeutsche Wortbildung”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 90: 106-121.

; Laabs 1974: 144

; Laabs 1974: 144 Laabs 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Laabs 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Laabs, Kurt 1974. „Zum slawischen Wortgut im Ostpommerschen”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 97: 143-150.

).

).

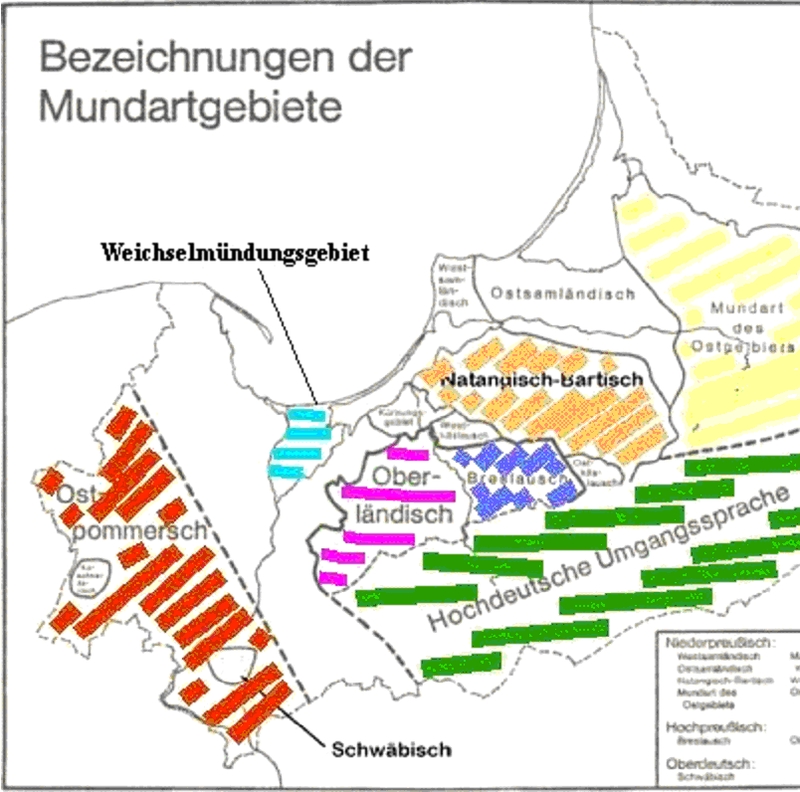

Illustration: German dialects of Prussia (the origins of the map is unknown).

The history of Mennonites

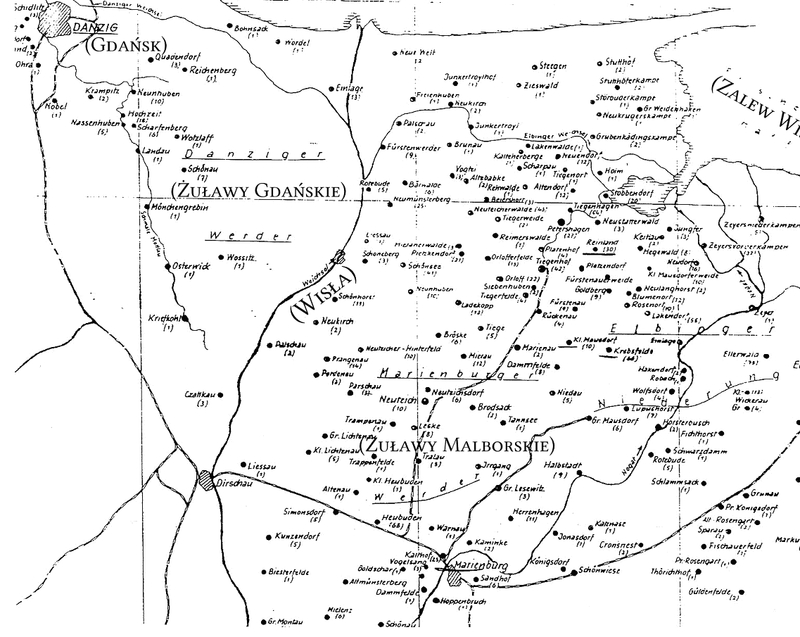

Illustration: the location of Mennonite villages in Prussia ca. 1800 (after: Johnson 1995

Johnson 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Johnson 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Johnson, Helen K. 1995. A tapestry of ancestral footprints: Groenings, Duecks, Ennses, Koops, Friesens, Kroekers. Lockport: Johnson.

: map 5).

: map 5).Mennonites are a religious group that arrived from Holland and started to settle down in Prussia (which was at that time a part of the Republic of Poland) in the 16th century. Mennonites stood out because of their radical pacifism which was based on the evangelical message of love towards one’s fellowmen. It did not meet with the acceptance of the authorities, especially the central ones. King Sigismund III Vasa tried to force the municipal authorities of Elbląg to impose full civic responsibilities on Mennonites, but this plea was ignored. Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki tried in turn accuse the Danzig Mennonites of heresy. His actions were blocked by municipal authorities; they were regarded as the king’s interference in the city’s internal affairs (Klassen 2009: 161-162

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

).

).

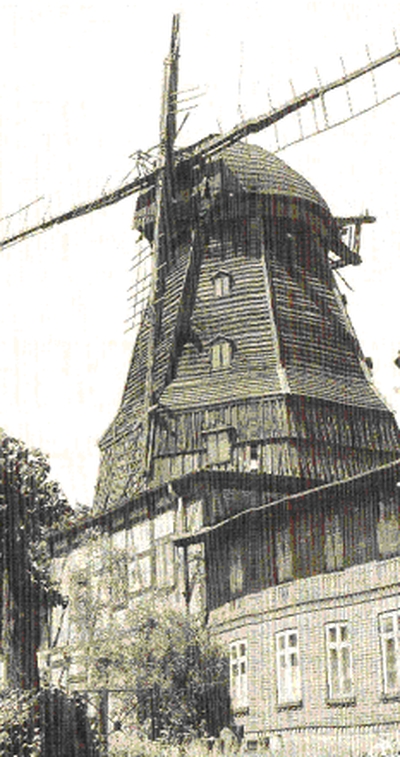

Illustration: Windmill around Wikrów (Ger. Wickerau; in the present day Elbląg district) – burnt in 2002 (source: Klassen 2009: 33

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

).

).Despite an initial fear of heresy, local authorities in Prussia valued Mennonites for their significant contribution to the economic growth achieved through sustenance of non-fertile lands with a help of technology brought from Holland. Because of that, the conditions imposed by their religion were generally respected, e.g. they were allowed to develop their own education system, and to replace military obligations with taxes. Additionally, the wording of vows was changed in order not to infringe the rules of their faith (Klassen 2009: 162, 168

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

). On the other hand, there were conflicts too, and the Mennonites’ faith was never treated on equal terms when compared to other churches, and Mennonites were required to pay taxes to Catholic and Protestant churches.

). On the other hand, there were conflicts too, and the Mennonites’ faith was never treated on equal terms when compared to other churches, and Mennonites were required to pay taxes to Catholic and Protestant churches.

Illustration: A Mennonite arcade house in Stablewia (source: Aktron / Wikimedia Commons).

When the Republic of Poland lost its control over Royal Prussia as a result of the first partition, the political situation turned out to be unfavourable for the Mennonites. Frederick William II, King of Prussia, issued an edict that restricted their chances to buy new lands (Mannhardt and Thiessen 2007

Mannhardt i Thiessen 2007 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mannhardt i Thiessen 2007 / komentarz/comment/r / Mannhardt, H. G. & Richard D. Thiessen 2007. „Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia (1744-1797)”, w: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. [http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/F754282.html].

). The ownership of parcels that did not belong to Mennonites was burdened with military service, and the Mennonites who bought them could not, in the face of the new law, count on the relief from this burden (Klassen 2009: 171, 173

). The ownership of parcels that did not belong to Mennonites was burdened with military service, and the Mennonites who bought them could not, in the face of the new law, count on the relief from this burden (Klassen 2009: 171, 173 Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

). Because of this, in 1787, ten years after the partition, the first wave of Mennonite colonisers moved to Russia, upon the invitation granted to them by Catherine the Great (Nieuweboer 2000: 116

). Because of this, in 1787, ten years after the partition, the first wave of Mennonite colonisers moved to Russia, upon the invitation granted to them by Catherine the Great (Nieuweboer 2000: 116 Nieuweboer 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nieuweboer 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Nieuweboer, Roger 2000. „Das Plautdiitsche der russlanddeutschen Mennoniten vor und nach der Aussiedlung”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 123: 115-144.

). Once moved, they transferred the contemporary Prussian Low German dialect from the Binnennehrung region and the northern part of Greater Żuławy (Ger. Großes Werder). It became the basis for the Plautdietsch language (Mitzka 1930: 6

). Once moved, they transferred the contemporary Prussian Low German dialect from the Binnennehrung region and the northern part of Greater Żuławy (Ger. Großes Werder). It became the basis for the Plautdietsch language (Mitzka 1930: 6 Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

, Ebb 1987: 66

, Ebb 1987: 66 Epp 1987 / komentarz/comment/r /

Epp 1987 / komentarz/comment/r / Epp, Reuben 1987. „Plautdietsch: Origins, Development and state of the Mennonite Low German Language”, Journal of Mennonite Studies 5: 61-72.

).

).When the privileges that freed Mennonites from military services were abolished in Russia between 1874-76, the group was forced to start searching for new lands, where they could live in accordance with their faith, and therefore the settlement of Mennonites in the Western hemisphere (Nieuweboer 2000: 116

Nieuweboer 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nieuweboer 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Nieuweboer, Roger 2000. „Das Plautdiitsche der russlanddeutschen Mennoniten vor und nach der Aussiedlung”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 123: 115-144.

).

).The group of Mennonites that left the U.S.S.R during the interwar period dwelt on today’s Poland territory for a short time before moving to South America. In May 1930, they were accommodated in transitional camps in present day Germany, including Hammerstein (Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen province, the present day Czarne in Człuchów district in Pomeranian Voivodeship), where they were quarantined. German dialectologists had a chance to analyse the language varieties that were used by them at that time. Examples of the samples gathered then are available below (Mitzka 1930: 10

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

).

Mennonites lived in Prussia until before World War II. In 1937, in Żuławy (Ger. Werder) there lived 5950 Mennonites (Driedger 1957

).

Mennonites lived in Prussia until before World War II. In 1937, in Żuławy (Ger. Werder) there lived 5950 Mennonites (Driedger 1957 Driedger 1957 / komentarz/comment/r /

Driedger 1957 / komentarz/comment/r / Driedger, Abraham 1957. „Marienburger Werder (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)”, w: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. [http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/M373080.html].

) who used local Low German dialects (Mitzka 1930: 11

) who used local Low German dialects (Mitzka 1930: 11 Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

). After World War II had ended, they were evacuated (Driedger 1957

). After World War II had ended, they were evacuated (Driedger 1957 Driedger 1957 / komentarz/comment/r /

Driedger 1957 / komentarz/comment/r / Driedger, Abraham 1957. „Marienburger Werder (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland)”, w: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. [http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/M373080.html].

).

).

Illustration: The first Mennonite temple in Elbląg used between 1590 and 1900 (source: Klassen 2009: 116

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

).

).Mennonites are classified as Germans or Dutch. They are considered to be an ethno-confessional group or a separate nationality (this is why a capital letter is used). In the U.S.S.R., Mennonites often identified themselves as Dutch, and their language as a dialect of Dutch or Frisian. As pointed out by de Graaf (2006: 383-384), repercussions by Germans affected such identification. Moreover, other Germans usually did not identify Mennonites as Germans because of their linguistic distinctiveness. When West Germany started to accept the immigration of so-called “late migrants” (Spätaussiedler), many people changed their nationality (so-called пятый пункт, or the 5th rubric in a Soviet passport, in which a citizen’s nationality was stated) from Dutch to German, mainly because of an opportunity to move to Germany (de Graaf 2006: 392

de Graaf 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

de Graaf 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / de Graaf, Tjeerd 2006. „The Status of an Ethnic Minority in Eurasia: The Mennonites and Their Relation with the Netherlands, Germany and Russia”, w: Ieda Osamu (red.) Beyond Sovereignty: From Status Law to Transnational Citizenship? Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University, s. 381-401.

).

).Mennonites – history of the linguistic situation

In the areas from where Mennonites arrived (Eastern Frisia and the Dutch province of Groningen), in the mid-16th century Low German was everyday language, whereas Dutch was used for religious purposes. In Western Prussia, Mennonites came upon another dialect of Low German, which they later adopted and enriched with elements brought from the West (Epp 1987: 65 Epp 1987 / komentarz/comment/r /

Epp 1987 / komentarz/comment/r / Epp, Reuben 1987. „Plautdietsch: Origins, Development and state of the Mennonite Low German Language”, Journal of Mennonite Studies 5: 61-72.

).

).Documents from the 18th century confirm a strong influence of Low German on Dutch language spoken by Mennonites, which still served a religious purpose then. In Danzig, Dutch language ceased to be used ca. 1800, giving way to Low German as spoken language and High German as written language (Mitzka 1930: 8-10

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

).

).Walther Mitzka stated that Russian Mennonites identify their Low German dialect as a Dutch heritage (Mitzka 1930: 10

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

). Gerhard Wiens, an American scholar who was born in the area of the present day Ukraine and writes about Russian loanwords in his language, define his mother tongue as Low German from the Malbork region of Żuławy (Wiens 1957: 93

). Gerhard Wiens, an American scholar who was born in the area of the present day Ukraine and writes about Russian loanwords in his language, define his mother tongue as Low German from the Malbork region of Żuławy (Wiens 1957: 93 Wiens 1957 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiens 1957 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiens, Gerhard 1957. „Entlehnungen aus dem Russischen im Niederdeutschen der Mennoniten in Rußland”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 80: 93-100.

).

).W. Mitzka believed that the dialect of Mennonites was a variety of Low Prussian dialect from the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, retained during the diaspora. However, there are also rival theories claiming that, in comparison to the neighbour languages, more Dutch and Frisian elements were included in the language of Mennonites (Moelleken 1987: 89

Moelleken 1987 / komentarz/comment/r /

Moelleken 1987 / komentarz/comment/r / Moelleken, Wolfgang W. 1987. „Die linguistische Heimat der rußlanddeutschen Mennoniten in Kanada und Mexiko”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 110: 89-101.

). According to W. Mitzka, diversity in dialects of so-called Russlandmennoniten (users of Plautdietsch) stems from the fact that they left Danzig as soon as the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, and because of that their speech retained many features that disappeared in Prussia by the 20th century (Mitzka 1930: 21

). According to W. Mitzka, diversity in dialects of so-called Russlandmennoniten (users of Plautdietsch) stems from the fact that they left Danzig as soon as the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, and because of that their speech retained many features that disappeared in Prussia by the 20th century (Mitzka 1930: 21 Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

).

).According to The Ethnologue, Plautdietsch is now used in Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Kazakhstan, Costarica, Mexico, Germany, Paraguay, and the United States.

ISO Code

ISO 639-3: Low German - nds, Mennonites' Plautdietsch - pdt; Middle Low German (including the lingua franca variety of the Hanseatic League) - gml.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

- Pomorze Tylne i Prusy Zachodnie

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- Adam 1893

- Pinnow 2006b

- Sanders 1982

- Breyer 2006

- Słabig 2009

- Foss 1971

- Putzger 1905

- Zielińska 2012

- Mitzka 1954

- Müller-Baden 1905

- Höhmann i Savedra 2011

- Łopuszańska 2008b

- Jenks i Sarnowsky 2009

- Herrmann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1911

- Turnbull 2011

- Siatkowski 1983

- Holsten 1947

- Winter 1967

- Laabs 1974

- Łopuszańska 2008a

- Steinke 1914

- Laude 1995

- Schemionek 1881

- Dorr 1877

- Shakespeare 1877

- ten Venne 1998

- Debus 1996

- Reifferscheid 1887

- Teuchert 1909

- Teucher 1910

- Oppenheimer 1975

- Mitzka 1928

- Lewis 2009

- Granzow 1982

- Laskowsky i Matthias 1926

- Matthias 1933

- Riemann 1970

- König 1991

- Pinnow 2006a

- Erben 1974

- Collitz 1911

- Jellinghaus 1892

- Scheel 1894

- Vereza i Kuster 2011

- Tressmann 2009

- Lindow 1926

- Hermann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1950

- Gottsched 1736

- Mitzka 1969

- Domansky 1911

- Gotard 2009

- Bogusławski 1900

- Drosihn 1874

- Götze 1922

- Dähnert 1781

- Toby 2000

- Dollinger 1976

- Mitzka 1930

- Zacharias i Neufeld 2003

- de Graaf 2006

- Klassen 2009

- Driedger 1957

- Wiens 2009

- Johnson 1995

- Mannhardt i Thiessen 2007

- Nieuweboer 2000

- Epp 1987

- Wiens 1957

- Moelleken 1987

- Neff 1953

- Mitzka 1955

- Jarczak 1972

- Rykała 2011

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- reklama restauracji w gwarze gdańskiej

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 1

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 2

- Gwary germańskie płn. Polski XX w

- Przesunięcie granicy odmian w Poznańskiem

- Prowincja Posen w 1849 r.

- Nowa Marchia

- Dialekty germańskie Prus

- Lokalizacja wsi menonickich w Prusach ok. 1800 r.

- Młyn w okolicach Wikrowa

- Świątynia menonicka w Elblągu

- Dialekty d.niemieckich w granicach Polski

- Mapa dialektów niemieckich - 1900

- Odmiany językowe na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska

- Odmiany językowe na południowy zachód od Gdańska

- Tekst dolnoniemiecki szryftem gotyckim

- Słownik Dähnerta

- Dom podcieniowy w Steblewie

- Mapa zasięgu językowego Hanzy

- Egzemplarz Barther Bibel

- Biblia z Schottland