Low German

Identity Kinship and identity

Indo-European languages -> German languages -> languages -> West Germanic -> Low German and Low Franconian(after: Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

)

)Language varieties that are closely related to the dialect under consideration include Low German (Low Saxon) varieties from Germany and the Netherlands, and also those used in the diaspora; additionally, to a lesser degree, Dutch languages (Frisian, Dutch) and Afrikaans. As a language which derives directly from Old Saxon, Low German is closely related to English. An extended family of West Germanic languages includes i. a. Frisian, Yiddish, and German (Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).

Illustration: Map of Low German dialects within the borders of the present day Poland. The situation in 1900 (after: König 1991

König 1991 / komentarz/comment/r /

König 1991 / komentarz/comment/r / König, Werner 1991. dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

).

).

Illustration: Map of German dialects. The situation in 1900 (after: König 1991: 230-23

König 1991 / komentarz/comment/r /

König 1991 / komentarz/comment/r / König, Werner 1991. dtv-Atlas zur deutschen Sprache. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

1).

1).As claimed by Herrmann-Winter, to this day there is no full dialectal geography of the former Pommern province (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 178

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

). As can be seen on the attached maps, scholars divide the dialects under attention in different ways

). As can be seen on the attached maps, scholars divide the dialects under attention in different ways

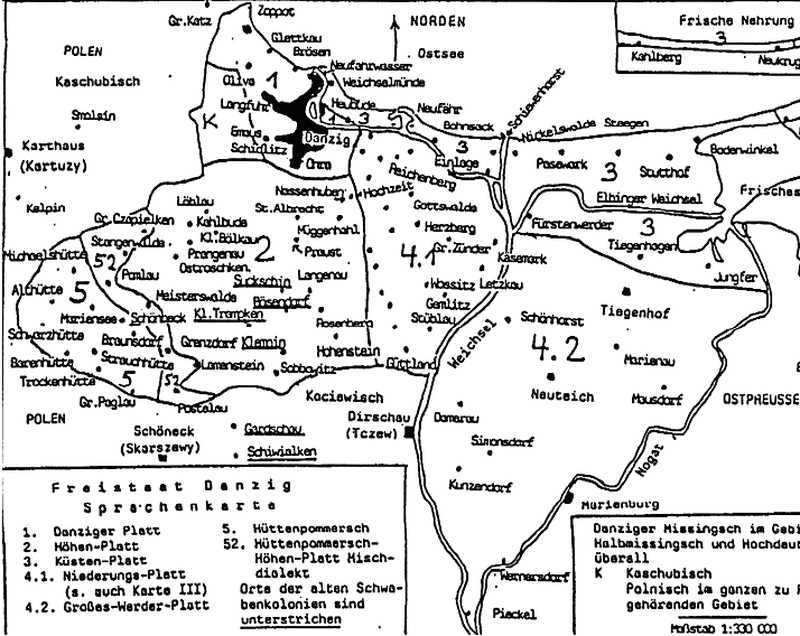

Illustration: Language varieties in the Free City of Danzig and the surrounding areas (after: Pinnow 2006a

Pinnow 2006a / komentarz/comment/r /

Pinnow 2006a / komentarz/comment/r / Pinnow, Jürgen (red.) 2006a. Danzjer Uuleschpeejel. München: Lincom Europa.

).

).

While Jürgen Pinnow (2006a: 13

Pinnow 2006a / komentarz/comment/r /

Pinnow 2006a / komentarz/comment/r / Pinnow, Jürgen (red.) 2006a. Danzjer Uuleschpeejel. München: Lincom Europa.

) distinguishes 10 German language varieties that are used in the Free City of Danzig, Łopuszańska (2008a

) distinguishes 10 German language varieties that are used in the Free City of Danzig, Łopuszańska (2008a Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008a. „Danziger Stadtsprache”, w: Marek Nekula & Verena Bauer & Albrecht Greule (red.) Deutsch in multilingualen Stadtzentren Mittel- und Osteuropas. Wien: Praesens-Verl.

), describing the same time and place, makes reference only to Low German, West Low Prussian and danziger missingsch, and it is primarily the question of minuteness of the division.

), describing the same time and place, makes reference only to Low German, West Low Prussian and danziger missingsch, and it is primarily the question of minuteness of the division.Apart from typically Low German dialects, in the urban areas one could also hear mixed dialects, so-called missingsch (e.g. Danzig – danziger missingsch). Scholars do not agree on the etymology of this name: it is derived either from Messing, the word for bronze which, as it is known, is an alloy of copper and tin (Erben 1974: 566

Erben 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Erben 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Erben, Johannes 1974. „Luther und die neuhochdeutsche Schriftsprache”, w: Friedrich Maurer & Heinz Rupp (red.) Deutsche Wortgeschichte. T. 2. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

), or from the definition of the process of mixing itself (Collitz 1911: 110

), or from the definition of the process of mixing itself (Collitz 1911: 110 Collitz 1911 / komentarz/comment/r /

Collitz 1911 / komentarz/comment/r / Collitz, Herrmann 1911. „Missingsch”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 110-113.

), or even from the name of city Miśnia (Ger. Meiβen) (Erben 1974: 566

), or even from the name of city Miśnia (Ger. Meiβen) (Erben 1974: 566 Erben 1974 / komentarz/comment/r /

Erben 1974 / komentarz/comment/r / Erben, Johannes 1974. „Luther und die neuhochdeutsche Schriftsprache”, w: Friedrich Maurer & Heinz Rupp (red.) Deutsche Wortgeschichte. T. 2. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

).

).Some of the varieties discussed constitute or constituted a separate language in the consciousness of the speakers. In 1639, Johannes Micraelius, rector of Pedagogium in Szczecin, was outraged because of the lack of priests who spoke Low German, and revulsion towards native language. However, Micraelius’s opinion did not necessarily reflect the true situation (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 173

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).In The Ethnologue’s database, Low German is treated as a unit. Among the dialects under consideration, The Ethnologue enlists: Marchian-Brandenburgian (which includes New Marchian), and identifies it with East Prussian (sic!); pomerano dialect from South America; Plautdietsch (Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages ratified by Germany, recognizes Low German in the following landen (states in Germany): Bremen, Hamburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, and Schleswig-Holstein. In the Charter ratified in the Netherlands, Low German was included under the name of Low Saxon. Polish linguistic politics does not recognise Low German.

Low German dialects were used predominantly by Germans. Manifestation of regional identity can be observed in the respective areas.

Bernhard Trittelvitz, a Pomeranian poet, used to write about his native language (Pomeranian) and land (Min Pommernland). In 1982, K. Granzow, also a poet, published a collection of texts of a reminiscent nature that refer to Pomerania; the collection included linguistic elements from the Low German dialect (Granzow 1982

Granzow 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Granzow 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Granzow, Klaus (red.) 1982. Typisch Pommern: Heiteres, Besinnliches und auch Wissenswertes über das Land am Meer. Frankfurt: Weidlich.

). In a similar publication from 1920s, which relates to the region of Posen province, only High German is used (Laskowsky and Matthias 1926

). In a similar publication from 1920s, which relates to the region of Posen province, only High German is used (Laskowsky and Matthias 1926 Laskowsky i Matthias 1926 / komentarz/comment/r /

Laskowsky i Matthias 1926 / komentarz/comment/r / Laskowsky, Paul & Marie Matthias (red.) 1926. Heimatklänge aus dem Osten eine Weihnachtsgabe für die ostmärkische Jugend. Berlin: Verlag des Deutschen Ostbundes.

). However, in 1933, one of its authors, M. Matthias, admitted that Posen dialect was unfamiliar to her before she had made some research in the field. She wrote: “The language in our land provides us with an insight into our folk nature – it confirms, above all, an old German imprint on our motherland” (Matthias 1933: 53

). However, in 1933, one of its authors, M. Matthias, admitted that Posen dialect was unfamiliar to her before she had made some research in the field. She wrote: “The language in our land provides us with an insight into our folk nature – it confirms, above all, an old German imprint on our motherland” (Matthias 1933: 53 Matthias 1933 / komentarz/comment/r /

Matthias 1933 / komentarz/comment/r / Matthias, Marie 1933. „Gibt es eine posensche Mundart?”, Heimatkalender für den Kreis Deutsch-Krone 21: 51-53.

).

).There are Pomeranian communities in the diaspora in the USA and Brazil, which have an identity based on awareness of distinct Pomeranian origin and language, distinct from a wider German community. Some former inhabitants of Warmia retained a strong sense of belonging to the region. Their identity might be influenced by the fact that, in comparison to other areas of Prussia, Warmia was unique because of a different faith (Catholicism) and different linguistic features, influenced by ca. three hundred years of the Polish rule (Riemann 1970: 114, 124-125

Riemann 1970 / komentarz/comment/r /

Riemann 1970 / komentarz/comment/r / Riemann, Erhard 1970. „Beobachtungen zur Wortgeographie des Ermlands”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 93: 114-153.

).

).

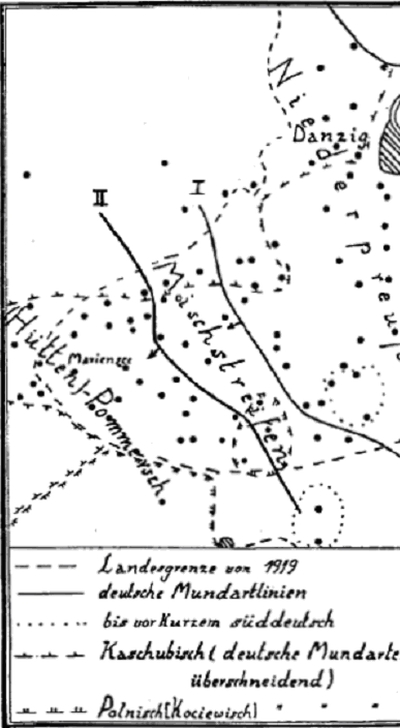

Illustration: Linguistic variations in the regions to the south-west of Danzig – the situation in 1922 (after: Mitzka 1928: 9

Mitzka 1928 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1928 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1928. Sprachausgleich in den deutschen Mundarten bei Danzig. Königsberg: Gräfe und Unzer.

).

).Low German dialects were also used by inhabitants with an ethnic background different from German, who lived in the areas where Low German was spoken. On the Kashubian coast, where hüttenpommersch dialect was spoken, both Kashubians and Germans spoke both Kashubian and German. Interestingly, the local Low German dialects (both hüttenpommersch and a local variation of Low Prussian) were regarded as Kashubian dialects as well (Mitzka 1928: 22

Mitzka 1928 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1928 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1928. Sprachausgleich in den deutschen Mundarten bei Danzig. Königsberg: Gräfe und Unzer.

). Danziger missingsch was used by all citizens of Danzig, regardless of their ethnic affiliation (Łopuszańska 2008a: 189

). Danziger missingsch was used by all citizens of Danzig, regardless of their ethnic affiliation (Łopuszańska 2008a: 189 Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008a. „Danziger Stadtsprache”, w: Marek Nekula & Verena Bauer & Albrecht Greule (red.) Deutsch in multilingualen Stadtzentren Mittel- und Osteuropas. Wien: Praesens-Verl.

). In Eastern Masuria, Russians – Old Believers who used Low German, dwelt there until the 1950s (Siatkowski 1983: 104

). In Eastern Masuria, Russians – Old Believers who used Low German, dwelt there until the 1950s (Siatkowski 1983: 104 Siatkowski 1983 / komentarz/comment/r /

Siatkowski 1983 / komentarz/comment/r / Siatkowski, Janusz 1983. „Interferencje językowe na Warmii i Mazurach”, Studia z Filologii Polskiej i Słowiańskiej XXI: 103-115.

).

).

ISO Code

ISO 639-3: Low German - nds, Mennonites' Plautdietsch - pdt; Middle Low German (including the lingua franca variety of the Hanseatic League) - gml.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

- Pomorze Tylne i Prusy Zachodnie

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- Adam 1893

- Pinnow 2006b

- Sanders 1982

- Breyer 2006

- Słabig 2009

- Foss 1971

- Putzger 1905

- Zielińska 2012

- Mitzka 1954

- Müller-Baden 1905

- Höhmann i Savedra 2011

- Łopuszańska 2008b

- Jenks i Sarnowsky 2009

- Herrmann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1911

- Turnbull 2011

- Siatkowski 1983

- Holsten 1947

- Winter 1967

- Laabs 1974

- Łopuszańska 2008a

- Steinke 1914

- Laude 1995

- Schemionek 1881

- Dorr 1877

- Shakespeare 1877

- ten Venne 1998

- Debus 1996

- Reifferscheid 1887

- Teuchert 1909

- Teucher 1910

- Oppenheimer 1975

- Mitzka 1928

- Lewis 2009

- Granzow 1982

- Laskowsky i Matthias 1926

- Matthias 1933

- Riemann 1970

- König 1991

- Pinnow 2006a

- Erben 1974

- Collitz 1911

- Jellinghaus 1892

- Scheel 1894

- Vereza i Kuster 2011

- Tressmann 2009

- Lindow 1926

- Hermann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1950

- Gottsched 1736

- Mitzka 1969

- Domansky 1911

- Gotard 2009

- Bogusławski 1900

- Drosihn 1874

- Götze 1922

- Dähnert 1781

- Toby 2000

- Dollinger 1976

- Mitzka 1930

- Zacharias i Neufeld 2003

- de Graaf 2006

- Klassen 2009

- Driedger 1957

- Wiens 2009

- Johnson 1995

- Mannhardt i Thiessen 2007

- Nieuweboer 2000

- Epp 1987

- Wiens 1957

- Moelleken 1987

- Neff 1953

- Mitzka 1955

- Jarczak 1972

- Rykała 2011

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- reklama restauracji w gwarze gdańskiej

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 1

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 2

- Gwary germańskie płn. Polski XX w

- Przesunięcie granicy odmian w Poznańskiem

- Prowincja Posen w 1849 r.

- Nowa Marchia

- Dialekty germańskie Prus

- Lokalizacja wsi menonickich w Prusach ok. 1800 r.

- Młyn w okolicach Wikrowa

- Świątynia menonicka w Elblągu

- Dialekty d.niemieckich w granicach Polski

- Mapa dialektów niemieckich - 1900

- Odmiany językowe na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska

- Odmiany językowe na południowy zachód od Gdańska

- Tekst dolnoniemiecki szryftem gotyckim

- Słownik Dähnerta

- Dom podcieniowy w Steblewie

- Mapa zasięgu językowego Hanzy

- Egzemplarz Barther Bibel

- Biblia z Schottland