Low German

Presence in everyday life

Prussia

Low German was the court language in Danzig until 1566 (exactly on the 3rd of June of this year the scribes switched to High German), but from 1564 onward, regulations of the city council were issued in High German (Łopuszańska 2008b: 223 Łopuszańska 2008b / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008b / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008b. „Sprachlichkeit Danzigs”, w: Andrzej Kątny (red.) Kontakty językowe i kulturowe w Europie. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo UG.

). Prior to this, Low German was mainly written language, used i.a. as a correspondence language of the Hanseatic League (compare: Sanders 1982

). Prior to this, Low German was mainly written language, used i.a. as a correspondence language of the Hanseatic League (compare: Sanders 1982 Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Sanders, Willy 1982. Sachsensprache. Hansesprache. Plattdeutsch. Göttingen: Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht.

). However, High German was also used for this purpose, e.g. in letters to the Teutonic Order, Polish king, and German-speaking cities (Łopuszańska 2008a: 183-185

). However, High German was also used for this purpose, e.g. in letters to the Teutonic Order, Polish king, and German-speaking cities (Łopuszańska 2008a: 183-185 Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008a. „Danziger Stadtsprache”, w: Marek Nekula & Verena Bauer & Albrecht Greule (red.) Deutsch in multilingualen Stadtzentren Mittel- und Osteuropas. Wien: Praesens-Verl.

).

).In his catalogue of legal texts written in Low German, Jellinghaus (1892: 75

Jellinghaus 1892 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jellinghaus 1892 / komentarz/comment/r / Jellinghaus, Hermann 1892. „Die Rechtsaufzeichnungen in niederdeutscher Sprache”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XVIII: 71-79.

) mentions some statutes of the Teutonic Order that were written in this language.

) mentions some statutes of the Teutonic Order that were written in this language.In 1881, August Schemionek reported that High German was not the only language used in public life by the inhabitants of the lands surrounding Elbląg – Low German remained home language of families that were settled for the longest period (Schemionek 1881: IV

Schemionek 1881 / komentarz/comment/r /

Schemionek 1881 / komentarz/comment/r / Schemionek, August 1881. Ausdrücke und Redensarten der Elbingschen Mundart. Danzig: Bertling.

).

).In the mid-19th century in Danzig, Low German was spoken by craftsmen and workers, but in the second half of the century it was still comprehensible for educated people. However, when Walther Domansky published his poems at the beginning of the 20th century, Low German was so unpopular that glossaries, or even translations to High German, had to be included in the editions (Łopuszańska 2008a: 188

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008a. „Danziger Stadtsprache”, w: Marek Nekula & Verena Bauer & Albrecht Greule (red.) Deutsch in multilingualen Stadtzentren Mittel- und Osteuropas. Wien: Praesens-Verl.

; Łopuszańska 2008b: 226

; Łopuszańska 2008b: 226 Łopuszańska 2008b / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008b / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008b. „Sprachlichkeit Danzigs”, w: Andrzej Kątny (red.) Kontakty językowe i kulturowe w Europie. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo UG.

).

).In the 19th century, danziger missingsch (also known as mochumsch) was a universal Danzig language (of all citizens, regardless of their ethnic identity). It was a language based on High German, with elements of Low German and Kashubian.

Pomerania

Low German was used in the chancellery of Pomeranian princes, and by the Hanseatic League (Scheel 1894: 57-58 Scheel 1894 / komentarz/comment/r /

Scheel 1894 / komentarz/comment/r / Scheel, Willy 1894. „Zur Geschichte der Pommerischen Kanzleisprache im 16. Jahrhundert”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XX: 57-78.

). In 2008, Pomeranian was given a status of official language in five districts of Espírito Santo state (Brazil) (Höhmann and Savedra 2011

). In 2008, Pomeranian was given a status of official language in five districts of Espírito Santo state (Brazil) (Höhmann and Savedra 2011 Höhmann i Savedra 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Höhmann i Savedra 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Höhmann, Beate & Mônica M. G. Savedra 2011. „Das Pommerische in Espírito Santo: ergebnisse und perspektiven einer soziolinguistischen studie”, Pandaemonium Germanicum 18. [http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1982-88372011000200014&lng=en&nrm=iso]

; Vereza and Kuster 2011

; Vereza and Kuster 2011 Vereza i Kuster 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Vereza i Kuster 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Vereza, Claudio & Sintia Bausen Kuster 2011 [?]. O povo pomerano no es. [http://www.rog.com.br/claudiovereza2/mostraconteudos.asp?cod_conteudo=735] #link nie działa, zostawić?#

). Ultimately, Pomeranian is to be given all rights of official language that would be equal to Portuguese (Tressmann 2009: 2

). Ultimately, Pomeranian is to be given all rights of official language that would be equal to Portuguese (Tressmann 2009: 2 Tressmann 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tressmann 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Tressmann, Ismael 2009. A Co-oficialização da língua pomerana. [http://www.farese.edu.br/pages/artigos/pdf/ismael/A%20co-oficialização%20da%20L%20Pomer.pdf]

).

).The media

The issue of Low German dialects is not touched upon in the media of the German minority in Poland. There are websites devoted to Low German dialects from the area of the present day Poland, and their cultural heritage. The websites themselves are usually maintained in (High) German or English. There is a Brazilian blog about Pomeranian, Pomerano (Pommersch); it is maintained by Renaldson Boon. The blog contains i.a. a dictionary, grammar section, and links to other materials (http://www.pommerplattdutsch.blogspot.com/). Compositions in the dialects of Danzig and the neighbouring areas are available in the archives of Internet forum, Danzig.de (http://forum.danzig.de/archive/index.php/f-102.html?s=759ea6c7462461248aa330efb44489f5).In addition, there are three linguistic versions of Internet project Wikipedia, that are edited in the following Low German varieties:

- http://nds.wikipedia.org – Low German Wikipedia, created mainly in the varieties spoken in Germany

- http://nds-nl.wikipedia.org/ – Low Saxon Wikipedia, created in the varieties spoken in the Netherlands, using a common orthography which was developed in 2011

- http://incubator.wikimedia.org/wiki/Wp/pdt/Hauptsied – experimental Wikipedia site created in Plautdietsch

Religious life

Unlike in the Duchy of Prussia, Low German played a certain role in religious life in the 16th century in Royal Prussia which was under the jurisdiction of Polish king. Low German was the sole language of services and sermons in Eastern Prussia, and Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible was the only one valid in this area.Inscriptions in Low German were made on bells from Joachim Carstedt’s workshop which provided bells to Poznań district as well, e.g. to Kłecko near Gniezno (Lindow 1926: 10

Lindow 1926 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lindow 1926 / komentarz/comment/r / Lindow, Max 1926. Niederdeutsch als evangelische Kirchensprache im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert. Greifswald, Panzig.

). Inscriptions in Low German could be found in churches in Danzig: in Saint Mary’s Church (there was an inscription of the High Gate: “Konigynne der hemele bidde vor uns” – “Queen of Heaven, pray for us”) and in Saint John’s Church.

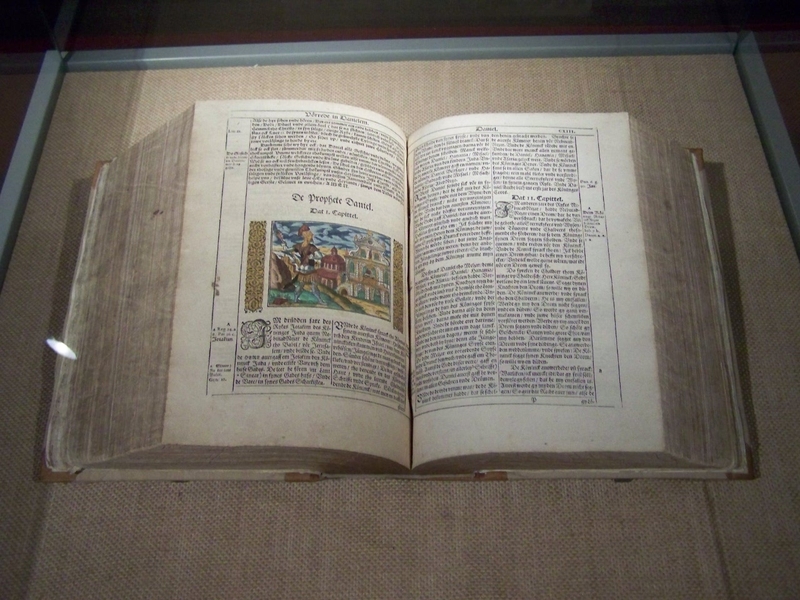

In Pomerania, Low German was for a long time important in religious life: it was language of both religious publications and ecclesiastical documents. Bogislaw XIII (1544-1606), prince of Worora and Szczecin, ordered publication of the Bible in Pomeranian („in Pommerischer sprach”), which led to the publication of Barther Bibel.

). Inscriptions in Low German could be found in churches in Danzig: in Saint Mary’s Church (there was an inscription of the High Gate: “Konigynne der hemele bidde vor uns” – “Queen of Heaven, pray for us”) and in Saint John’s Church.

In Pomerania, Low German was for a long time important in religious life: it was language of both religious publications and ecclesiastical documents. Bogislaw XIII (1544-1606), prince of Worora and Szczecin, ordered publication of the Bible in Pomeranian („in Pommerischer sprach”), which led to the publication of Barther Bibel.Herrmann-Winter writes that “even in the first half of the 18th century, Low German was allowed to have had some function in ecclesiastical language of Pomerania, even after deaths in the 17th century of ministers who had Low German sermons in Rügen and Kołobrzeg as the last ones” (Hermann-Winter 1995: 173

Hermann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Hermann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).Literature

Pomerania

Illustration: a copy of Barther Bibel (after: By Klugschnacker (Own work) [CC-BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons).

In the 16th century, Low German (or rather Mid-Low German) became the literary language in Pomerania; poetry and academic literature was published in this language. In 1588, the Bible was printed – Barther Bibel. According to statistics compiled by Borchling and Claussen, the Bible included 111 of the most important places of printing of Low German texts; in Szczecin, 54 publications in this language were printed (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 172

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

). In the 19th and 20th centuries, works were published in local linguistic variations.

). In the 19th and 20th centuries, works were published in local linguistic variations.In 1863, volume of poetry Kuddelmuddel was published by Oswald Palleske (1830-1913) from the region around Drawsko Pomorskie (Ger. Dramburg).

Dramatist Herrmann Jahnke (1845-1908), author of e.g. De Swestern, was connected not only to Pomerania, but also to Posen province (he studied in a gymnasium in Czarnków).

In 1900, Paul Gent, who was born in Berlin, published the comedy De dumme Johannken, which he translated into the dialects of Białogard (Ger. Belgard) and Drawsko Pomorskie (Ger. Dramurg) with a help of a relative of his wife. Wilhelm Baller, who was born in Garnki (Garchen) village near Kołobrzeg (Kolberg), wrote Leiwen un Lewen in 'schön Pommerland' (published post-mortem in 1913).

Even the end of World War II did not stop the development of Pomeranian literature. After the War, several authors were active, e.g. Klaus Granzow (from the region around Słupsk), Bernhard Trittelvitz (from the region around Białogard), and Fritz Dittmer, associated with Szczecin. In 1969, anthology of Pomeranian literature Pommersche Literatur. Proben und Daten, edited by Fritz Raeck, was published.

Prussia

In the play Elisa. Eine Newe und lustige Comödia, which was staged by Philipp Weiner and the pupils of Academic Gymnasium in Danzig, one of the characters speaks some of his lines in Low German. Erbsenschmeckerlied is one of the best known folk songs in Eastern Prussia. It was written in 1647 by Martin Weiβ, minister from Sępopole (Ger. Schippenbeil). The songs tells the story of a peasant from Pełkity (Ger. Polkitten). The village was situated on the Polish-Soviet border, and does not exist anymore. The character arrived in Sępopole to sell peas. The inhabitants of the city wanted to take only small samples from him, for free, and the peasant does not agree:Tom kranket, schert ju hen, well ji se all uthschmecken? Geft Gelt, ji goden Lüd, wat bill ji ju wol en! Well ji op juner Gren fet Arffteschmeckers sen?There is a Low German speaking character in the play, Die Pietisterey im Fischbein Rocke (Gottsched 1736

(after: Ziesemer 1950: 152Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer, Walther 1950. „Der Anteil des deutschen Osten an der niederdeutschen Literatur”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 129-139.)

Gottsched 1736 / komentarz/comment/r /

Gottsched 1736 / komentarz/comment/r / Gottsched, Luise A. V. 1736. Die Pietisterey im Fischbein-Rocke. Rostock: „auf Kosten guter Freunde”. [http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/491/1]

), her name is Frau Ehrlichen. A sample of the character’s line reads as follows:

), her name is Frau Ehrlichen. A sample of the character’s line reads as follows:I! du Schelm! Wat eck von dy hebben wöll? Eck frag dy, wat du von myner Dochter hebben wöllst? du verfloockter Hund!The play was written by Luise Adelgunde Victorie Gottsched nee Kulmus from Danzig, but fragments of the text were translated to Low German by her spouse Johann Christoph who was born in Królewiec (Ger. Königsberg, presently Kaliningrad), and spoke the dialect of this city (Ziesemer 1950: 154

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r / Ziesemer, Walther 1950. „Der Anteil des deutschen Osten an der niederdeutschen Literatur”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 129-139.

).

).In comedy from 1765, staged in Reszel (Rößel, today in Kętrzyn district), there are two songs in Low German: Ona Moda heft ene Meddelmagd, die de Gäns vom Howa jagd and Starwe motte alla Lüd — tram, tram, traiche, — Der eine morge, de angre hüd — tram, tram, traiche (Ziesemer 1950: 154

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r / Ziesemer, Walther 1950. „Der Anteil des deutschen Osten an der niederdeutschen Literatur”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 129-139.

).

).In the 18th century, the so-called moral weeklies (Moralische Wochenschriften) were issued. They were periodicals modelled on the English publication The Tatler and German publications like Der Vernünftler and Der Patriot. The periodicals included prose texts sent by the readers, often written in a mixture of Low German and High German. One can observe a process of searching for a proper phrase while writing in local dialects (Mitzka 1969: 81

Mitzka 1969 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1969 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1969. „Danziger Niederdeutsch in Moralischer Wochenschrift 1741-1743”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 92: 81-93.

). Anna Renata Breyne was another author who used the 18th century Low German in her poetical letters. Excerpts from her works were published by Walther Domansky (Domansky 1911

). Anna Renata Breyne was another author who used the 18th century Low German in her poetical letters. Excerpts from her works were published by Walther Domansky (Domansky 1911 Domansky 1911 / komentarz/comment/r /

Domansky 1911 / komentarz/comment/r / Domansky, Walther 1911. „Anna Renata Breyne's aus Danzig plattdeutsche Gedichte”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 140-144.

). Other remarkable authors from Danzig who wrote in Low German were: Kurt Gutowski, Herbert Sellke, Gustav Kross, Jürgen Pinnow, and Maks Schemke.

). Other remarkable authors from Danzig who wrote in Low German were: Kurt Gutowski, Herbert Sellke, Gustav Kross, Jürgen Pinnow, and Maks Schemke.Poetry written in Low German by Karl Groth and Fritz Reuter was so popular that it contributed to the development of writing in the Prussian variety of Low German. Robert Dorr from Elbinger Niederung (the eastern part of the Elbląg region of Żuławy) published a collection of poems Tweschen Wiessel on Noagt (1864), in addition to minor prosaic texts, and a translation of The Merry Wives of Windsor by William Shakespeare.

Many compositions written in Low German were published in Preußischen Provinzialblättern, periodical that was first issued in 1842; those included songs and prose, e.g. short story Dat Spook, written in Elbląg dialect. In addition, Ziesemer recommends sources like Völkerstimmen by Firmenich, Preußische Volkslieder by Frischbier and Liederschrein by Plenzat (Ziesemer 1950: 154-155

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r / Ziesemer, Walther 1950. „Der Anteil des deutschen Osten an der niederdeutschen Literatur”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 129-139.

).

).Walther Domansky (1860-1936), apart from his literary work (e.g. volumes of poetry: Danziger Dittchen (1903), Ein Bundchen Flundern (1904)) conducted research on the dialect itself and literature written in it. In the 1930s, texts by “Pensioner Poguttke” appeared in the Danzig press. He was a character created by Fritz Jänicke, a journalist and columnist of Danziger Neuesten Nachrichten, author of humorous texts in danziger missingsch. A lexicon of Danzig speech was included in his poem Kleiner Danziger Sprachführer (Gotard 2009

Gotard 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Gotard 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Gotard, Marek 2009. „Gdańsk okiem Poguttkego: z bówkami na machandel”, Trojmiasto.pl 24 lipca 2009. [http://www.trojmiasto.pl/wiadomosci/Gdansk-okiem-%20Poguttkego-z-bowkami-namachandel-n33909.html]

).

).About the same time, Ernst Frieböse created texts in the dialect of Żuławy Malborskie (Ger. Großes Werder). The examples of his humorous texts written in the dialect are as follows: Foorts tom Bejuche (1936), Pust di man nich opp (1939), and Zookerschnut (1937).

New Marche

Karl Löffler (1821-1874) wrote in New Marchian, under the pseudonym “Nümärker”. Löffler was born in Berlin, but when he was a child, he moved to Tarnów (Ger. Tornow), village near Gorzów Wielkopolski (Landsberg an der Warthe) where his father, a minister, was assigned.Opinions

Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803), born in Morąg (Ger. Mohrungen), described Low German dialect as “good-natured, harsh, naïve” (Ziesemer 1950: 149 Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer 1950 / komentarz/comment/r / Ziesemer, Walther 1950. „Der Anteil des deutschen Osten an der niederdeutschen Literatur”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XXXVII: 129-139.

).

).Polish historian Wilhelm Bogusławski (1825-1901) considered Low German dialects of West Pomerania to be “jargon”, into which the Slavic language had turned under Saxon influence (Bogusławski 1900: 312-313, 611

Bogusławski 1900 / komentarz/comment/r /

Bogusławski 1900 / komentarz/comment/r / Bogusławski, Wilhelm 1900. Dzieje Słowiańszczyzny północno-zachodniej aż do wynarodowienia Słowian zaodrzańskich. T. IV. Poznań: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.

).

).Examples

Samples of literature

The poem presented below was written by Bernhard Trittelvitz (1878-1969) from the region around Białogard (Ger. Belgard). After World War II, Trittelvitz started to compose in Pomeranian. In 1964, he was presented Pommerscher Kulturpreis award, granted by Pommersche Landsmannschaft (Pomeranian Association).| Bernhard Trittelvitz Mien Mudderspraak | Bernhard Trittelvitz My mother tongue |

| To jede Tiet, bi Dag un Nacht, bi Sünnenschien un Daak, deep in mien Harten singt un lacht Mien leeve oll Mudderspraak. Se kennt mi al as lüttes Kind, dat noch keen Hooch verstünn, un doch mit Busch un Bloom und Wind up Plattdüütsch snacken künn. [...] Ik segg di, Jung, so hüürd ik dat, as ik noch ganz, ganz lütt. Keen Wunner, dat uns Pommersch Platt deep in mein Harten sitt. |

At every time, in day or night, When the sun shines and in the dark, Deep in my heart sings and laughs My beloved mother tongue She knows me well as a little child, That does not understand High German yet, But with a bush, a flower and the wind Can talk in Low German […] I’m telling you, my boy, I’ve heard it, When I was very little. No wonder why our Pomeranian dialect Lays deep in my heart. |

The full text of the poem and the sound file are available on the website: http://grosstuchen.cwsurf.de/Trittelvitz.htm.

The text below is a part of a series of Danzig jokes about Bollermann and Welutzke. It was written in Low German dialect of Danzig (danzjer platt) – unlike danziger missingsch it is variety which is specifically Low German in its character:

Oan eenem Morje koam Welutzke no de Lange Brügg jehompelt. “Nanu, wat es mett di?” froch Bollermann. “Joo,” seed Welutzke, “eck häb soon Riete emm linksche Foot, dat eck kum utholle koan.”– “Joo, joo, leewer Jan,” meend Bollermann, “dat kömmt so mett dem Öller.”– “Nee,” seed Welutzke, “dat kan niçh vom Öller kome. Mien rechtschet Been es doch grod so olt, dat deit mi gor niçh wee.”– “Na,” oantword Bollermann, “dänn kömmt dat vom Suppe!”To compare, what follows is a joke about Bollermann written in mixed dialect of Danzig, i.e. danziger missingsch:

(author: Max Schemke, after: Pinnow 2006b: 14Pinnow 2006b / komentarz/comment/r /

Pinnow, Jürgen (red.) 2006b. So lachte man in Danzig. München: Lincom Europa.).

Härr Bollermann, Se sind aber 'n priema Tänzer!

Ach wissen Se, ich hab ne Weil inne Bierbrauerei ausjeholfen und so bin ich jewehnt, Fässer zu rollen!

(after: Pinnow 2006b: 22Pinnow 2006b / komentarz/comment/r /

Pinnow, Jürgen (red.) 2006b. So lachte man in Danzig. München: Lincom Europa.)

Proverbs, sayings, folklore

- northern dialect of the Noteć region from Niekursk (Ger. Nikosken; in the present day Czarnkowo-Trzcianka district of Greater Poland), with translation to High German and English:

Ụt di šọᵘa dā't mã nụ̈ št fetjãlla – Aus der Schule darf man nichts erzählen –'One should not tell about anything what happened at school’.

Hẹ is met allã hụnã hist – Er ist mit allen Hunden gehetzt – 'He is being chased by all the dogs'.

Hẹ löt zik d' botti fam brōd' ni naimã – Er lässt sich die Butter vom Brote nicht nehmen – ‘He does not allow anyone to take his bread from him’.

(Steinke 1914: 51Steinke 1914 / komentarz/comment/r /

Steinke, Florian 1914. „Sprachproben aus Niekosken, Kreis Czernikau (Provinz Posen)”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung XL: 48-54.)

- The further Pomeranian dialect from the valley of Parsęta River, in the region of Białogard (Ger. Belgard; in the present day West Pomeranian Voivodeship), with translation to High German and English:

Vo frisch Luf u frisch Bodde is no kain dood bläwe – An frischer Luft und frischer Butter ist noch keiner gestorben – ‘Nobody ever died from fresh air or fresh butter’.

Wenn ma dem Düwel de klaine Finge jifft, nimmt hai gliek de janz Hand – Wenn man dem Teufel den kleinen Finger reicht, nimmt er gleich die ganze Hand – ‘If one gives his finger to the devil, he will take the whole hand’.

Dai best Keech hätt dai Nåwe – Das Beste haben immer die anderen – ‘The best things always belong to someone else’.

Besåpen Keerls un klain Kiene bräke sich nischt – Betrunkene Kerle und kleine Kinder brechen sich nichts – 'Drunk men and little children never break’.

Krauç u Fruuçes rueniere ne Mann – Gastwirtschaft und Frauen ruinieren einen Mann – ‘Hospitality and women can ruin a man’.

(after: Laude 1995: 391-406Laude 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Laude, Robert 1995. Hinterpommersches Wörterbuch des Persantegebietes. Köln: Böhlau.)

- Dialect from Bobolice (Ger. Bublitz; presently in Koszalin district) – a riddle

Raue raue reip,

Wo gael is dei peip!

Wo schwart is dei sack,

Wo d'gael peip inne stak!

(Answer: gaelmoer / gelre.)

(Drosihn 1874: 147Drosihn 1874 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drosihn, Friedrich 1874. „Vierzig Volksräthsel aus Hinterpommern”, Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie V: 146-151.)

- Dialect from the region around Szczeniek (Neustettin; in the present day West Pomeranian Voivodeship) – a riddle

Rôe, rôe rîp,

Wo gael is dei pîp!

Wo swart is dei sack,

Wo dei gael pîp drin stack.

(Answer: gaelmöe.)

(Drosihn 1874: 149Drosihn 1874 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drosihn, Friedrich 1874. „Vierzig Volksräthsel aus Hinterpommern”, Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie V: 146-151.)

Samples of dialects

Wenker’s sentences

- South further Pomeranian dialect from Obrowo (Ger. Abrau in former Western Prussia; in the present day Tuchola county in Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship) – a sample from Wenker’s sentences (Wenkersätze)

Įm wintə flaijə dai drȫjə blę̄ də į də lųft ɒrų̈ mə – ‘In the winter, dry leaves spin in the air’.

T hȫt fōts ųp męt suijəd, dę wāt dat wę̄ də wędə bę̄ tə –'Soon, it will stop snowing and start to brighten up’.

Lęj kǭlə į də ǭwə, dat d mę̄ ltχ bol ɒna kǭkəd fįŋ̄t –'Put the coals in the stove, so that the milk starts boiling soon’.

Dai gaud ol mį̄š įs męt m̥ pę̄ d ųm īz įbrǭkə ų į d kol wǭtə falə – 'The ice broke under the good, old man and his horse, and both of them fell into the water’.

Hai įs fə faiə ędə zǫ̈ s wę̄ lχə stų̄ wə –'He died four or six weeks ago’.

(collected by Maria Semrau, after: Götze 1922: 105Götze 1922 / komentarz/comment/r /

Götze, Alfred 1922. Proben hoch- und niederdeutscher Mundarten. Bonn: Marcus & Weber.)

Other samples

- Southern dialect of the Noteć region from Rogoźno (Ger. Rogosen; presently in Oborniki district in Greater Poland):

A bųš įs dǫ a hāw rǫk, zęjt t fǫs, ų lęjt zįk hįnǫ d ęg. Wōe rōuk įs, mųt ōuk fǖe zįn, dįŋkt t fǫs, ų lęjt zįk ųpǫ męshōupǫ. Dat įs mā zōǫ ǫ̈̄ wegaŋk, zę̄ d d fǫs, az ęm d lę̄ de ȫwed ōrǫ trękt wǫ̈̄. Tįs ōuk wǫ mā blōus zo̱ ǫn zęg, zęjt t fǫs, dat mī d būrǫ wįlǫ tųm gāshārǫ maukǫ.

(collected by Albert Koerth, after: Götze 1922: 103Götze 1922 / komentarz/comment/r /

Götze, Alfred 1922. Proben hoch- und niederdeutscher Mundarten. Bonn: Marcus & Weber.)

- New Marchian dialect from Łupowo (Ger. Loppow; in the present day Gorzów district):

Kǫr̯ tə jəšiχtə fan lǫpə. Tįs twǭr̯ š man klēn, mīn haimātdǫ̈̄ r̯ p lǫpə — węnjə an ēn ęŋə r̯ įnkǭm̄, zįnjəōk ant andər̯ balə węder̯ r̯ ūt — awər̯ t hęt dǫmēr̯ ar̯ lę̄ ft as manχēnə šdat męt zęχsiχ dauzn̥ t inwǭnər̯ , di far̯ kǫr̯ tn̥ nǫxn̥ dǫ̇ r̯ p jəwęst is.

(collected by Hermann Teuchert, after: Götze 1922: 99-100Götze 1922 / komentarz/comment/r /

Götze, Alfred 1922. Proben hoch- und niederdeutscher Mundarten. Bonn: Marcus & Weber.)

- Dialect from Elbląg (Ger. Elbing):

Wo Schinder wer oech Butterbrod esse, wenn oech Kuche esse kann!Dialect of Lipno (before the War in Warsaw Voivodeship, in the present day Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship)

Na Hochjitterherrche, – höllterblöffig, das es meenst so als wi stobbekopsch.

(How a Berliner imitates dialect of Elbląg:) Jattche, Jattche! Komm schnall ans Fanster, die

Schnallpost es all bei Schmalzers om de Ack!

(Schemionek 1881: 49, 51, 53Schemionek 1881 / komentarz/comment/r /

Schemionek, August 1881. Ausdrücke und Redensarten der Elbingschen Mundart. Danzig: Bertling.)

Mɛm zɛt `am dɛš `o šrɛft `ɛnə brẹ̄ị̆f na ɛmarə – ‘Mum is sitting in the chair and writing a letter to Emma'.

Dat ćleiɘ ćint šp'iěld zɛć `em zānt mɛt ɣlās `o somfeiɘd zɛć dl'ińćɘ hānt –' A little child was playing with glass in the sand, and was cut on the hand’.

M'ị̄ ʓ́ āʓ́ə fǎ'lọụ̌ə ɣ́estərə `opəm haf z'ị̄n p'ị̄p; v́ ị̄əs fynə vāt, x́ ćre t `enə halvə ɣ́ilə – 'My grandpa lost his pipe yesterday in the yard; whoever finds it, he will be given half a gulden’.

(Foss 1971: 104-105, 109Foss 1971 / komentarz/comment/r /

Foss, Gustaw 1971. Die niederdeutsche Siedlungsmundart im Lipnoer Lande. Poznań: Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk.)

State of knowledge

Recordings

Recordings of Low German speech were included in a collection of records Lautdenkmal reichsdeutscher Mundarten (i.e. a sonic memorial of dialects of the Third Reich), created in 1936-37 as a gift for Adolf Hitler. The material that survived until the present day includes recordings from Elbląg (Elbing), Danzig and Czechynia (Zechendorf; in the present day Wałcz district in Western Pomeranian Voivodeship). The recordings from the Lautdenkmal collection and other recordings in Low German are available in a digital form on a website maintained by Wolfgang Näser (http://staff-www.uni-marburg.de/~naeser/ld00.htm).Archive of recordings can also be found on an Internet website dedicated to Tuchoma village (Groß Tuchen; in the present day Bytów district in Pomeranian Voivodeship): http://grosstuchen.cwsurf.de/Plattdeutsch.html. On this amateur website, recordings of Pomeranian dialects from various sources can be found.

The archives, maps, atlases

The Deutscher Sprachatlas project (conducted at Marburg University) has an archive of material concerning all German dialects. From 1887 onwards, the project collects translations of forty sentences formulated by Georg Wenker. At the very beginning of his work, the researcher asked former teachers of village schools to translate the sentences into a local dialect. Maps showing where respective linguistic features occur were created on the basis of the sentences. The exemplary sentences in Obrów (Ger. Abrau) dialect were quoted before. The whole atlas in a digital form is available on the website: http://www.diwa.info.Pictures, films

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r49hjnWNUGk – a TV spot that summarises the situation of people of Pomeranian origin who live in Brazil, and shows various aspects of their culture. The spot features a few utterances in Pomeranian. The documentary film Pomeranos, a Trajetória de Um Povo about Pomeranians in Brazil is also available to watch, (the film’s trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8vLCnV_LSY oraz http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z8auy5e3yD4). Additionally, a report about Brazilian Pomeranians aired on German television Deutsche Welle (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DdJOZA0710).Resources and organisations

Bibliography Die plattdeutschen Autoren und ihre Werke, compiled by Peter Hansen, is available on the Internet. It is a secondary-source bibliography, compiled on the basis of several primary-source bibliographies (including the abovementioned bibliography from Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung). In Hansen’s bibliography, it is possible to search for Low German authors by location (there is a whole separate unit devoted to “former German lands”, divided into respective regions and towns).Prize Pommerscher Kulturpreis is awarded by Pomeranian Association (Pommersche Landsmannschaft) that functions in Germany, and is a part of the Union of the Expelled (Bund der Vertriebenen). It is granted for cultural work in general, not only for writing in Low German dialects.

In Wisconsin (the USA), Pommerscher Verein Central Wisconsin was established. It is an association the aim of which is, among other things, the “preservation of the language and heritage of the ancestors who migrated mainly from the Prussian provinces of Pomerania, Western and Eastern Prussia, and Posen”. On the website run by the association, one can find e.g. a list of Pomeranian proverbs (http://www.pvcw.org/page.aspx?index=00000040), like Smecht goot, kopp di uk wat, ‘Sure it tastes nice; buy one for yourself too’.

On the website maintained by Karl-Heinz Jessner, native speaker of Danzig variety of Low German, resources like glossaries and poetry can be found: http://www.jessner.homepage.t-online.de/danzig.htm.

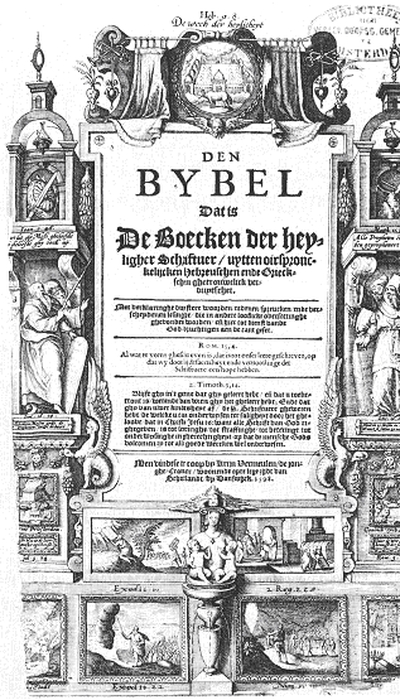

Use of the language in religious life Mennonite

Menno Simons (one of the early leaders of the movement that bears his name) and his co-workers used, most probably, the Bible in Low German that was translated by Jan Bugenhagen. However, Mennonites used other editions as well. In 1560, Nikolaes Biestkens, a Mennonite from Emden, published the Bible in Dutch. This translation was reissued several times, and used by the Dutch Mennonites. It was also published in Schottland, a town near Danzig (the present day Szkoty – a district of Danzig), for the local people’s needs. Theoretically, urban law did not allow Mennonites to print religious materials, but entrepreneur Quirin Vermeulen got past this regulation by ordering to print them in Haarlem (Neff 1953 Neff 1953 / komentarz/comment/r /

Neff 1953 / komentarz/comment/r / Neff, Christian 1953. „Biestkens Bible”, w: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. [http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/B54011.html].

, Klassen 2009: 122

, Klassen 2009: 122 Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

).

).

Illustration: The Bible from Schottland (after: Klassen 2009: 123

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Klassen 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland & Prussia. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

).

).In the 18th century, Mennonites used Low German in religious life and education, yet it was only supplementary to High German (Mitzka 1930: 9

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.

). After leaving Prussia, Mennonites retained not only their knowledge of Low German, but also High German which was used to religious and office purposes (Wiens 1957: 93-94

). After leaving Prussia, Mennonites retained not only their knowledge of Low German, but also High German which was used to religious and office purposes (Wiens 1957: 93-94 Wiens 1957 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wiens 1957 / komentarz/comment/r / Wiens, Gerhard 1957. „Entlehnungen aus dem Russischen im Niederdeutschen der Mennoniten in Rußland”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 80: 93-100.

). Presently, it is not common for Mennonites to speak High German (de Graaf 2006: 384

). Presently, it is not common for Mennonites to speak High German (de Graaf 2006: 384 de Graaf 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

de Graaf 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / de Graaf, Tjeerd 2006. „The Status of an Ethnic Minority in Eurasia: The Mennonites and Their Relation with the Netherlands, Germany and Russia”, w: Ieda Osamu (red.) Beyond Sovereignty: From Status Law to Transnational Citizenship? Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University, s. 381-401.

).

).The Bible in plautdietsch, language shaped during the diaspora, started to be printed in the 1980s. Before, High German (and prior to that- Dutch) was liturgical language for Mennonites. Fragments of the Bible were printed by, among others, J. W. Goerzen (Ute griksche hellje Schrefte: Proowe plautditscha Ewasating, 1968). The first full translation of the Bible to Plautdietsch, made by E. Zacharias and J. F. Neufeld, was printed in 2003 (Zacharias and Neufeld 2003

Zacharias i Neufeld 2003 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zacharias i Neufeld 2003 / komentarz/comment/r / Zacharias, Ed (tłum.) & John F. Neufeld (tłum.) 2003. De Bibel: the complete Bible in Plautdietsch. Winnipeg: Kindred Press.

).

).Media

A German radio station that broadcasts in Plautdietsch is available on website http://www.opplautdietsch.de/. There is also a Canadian website devoted to Plautdietsch, http://www.plautdietsch.ca/. Peter Wiens from Verein Plautdietsch-Freunde e. V. (The Association of Plautdietsch Friends) conducts blog http://peterwiens.blogspot.com/, where he discusses topics connected to Plautdietsch culture; the blog itself is written in High German.From 2001 onwards, the magazine Plautdietsch FRIND written in Plautdietsch is issued. In Canada, the magazine Journal of Mennonite Studies is issued. In the magazine, topics related to Mennonites and the Plautdietsch language are discussed.

Institutional background Verein Plautdietsch-Freunde e. V. is a German organization which represents Plautdietsch in the lobby of Federal Counsel for Low German (Bundesrat für Niederdeutsch).

Samples of dialects

Wenker’s sentence

- Friesenhof village (the present day Northern Kazakhstan district, Kazakhstan)

Em Winta fleiji de dreeiji Bläda enni Lofft romm – ‘In the winter, dead leaves spin in the air’.

Dit heat foat opp to schnii, dann woat dant Wada wada bäta – 'Soon, it will stop snowing, and start to brighten up’.

Do Koali emm Oawi, daut de Maltk bold aunfangt to koaki – 'Put the coals in the stove, so that the milk starts boling soon’.

Do godi oli Maun ess mett dem Peat derchit Iess gibroaki enn enn daut kolldi Woata jiffolli – 'The ice broke under the good, old man and his horse, and both of tchem fell into the water’.

Dit ess verr vea oda sass Wäatch jischtorrwn – 'He died four or six weeks ago’.

(after: Mitzka 1930: 18Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.)

- Felsenbach village (Dnipropetrovsk district, Ukraine)

Em Winta flegen de dreji Bleda eni Loft eromma – ‘In the winter, dead leaves spin in the air’

Daut heat vots op to schnien, dau woat daut Wada wada beta – 'Soon, it will stop snowing, and start to brighten up’.

Do Kuolen em Uowen, daut de Melk bolt aun to keken fangt – 'Put the coals in the stove, so that the milk starts boiling soon’.

De godi ola Maun eß metim Peat derchit Is jebreaken en em kolden Wota jivollen – 'The ice broke under the good, old man and his horse, and both of them fell into the water’.

He es ve vea oda saß Weakj jistorwen – 'He died four or six weeks ago’.

(after: Mitzka 1930: 15Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.)

- Margenau village (currentlyly Om district, Russia)

Em Winta flegi de vodrejdi Bleda enni Lofft erom – ‘In the winter, dead leaves spin in the air’.

Daut het vot's ob to schniei, dann wot daut Wada aulwadä beta – 'Soon, it will stop snowing, and start to brighten up’.

Do Kohli enn dem Owi, daut die Malk bold aun to koki fangt – 'Put the coals in the stove, so that the milk starts boiling soon’.

De godi old Maun es mett sien Peed derchim Is gibrauki, enn daut koldi Wota gifolli – 'The ice broke under the good, old man and his horse, and both of tchem fell into the water’.

He es verr vea oda sas Wek gistorwi – 'He died four or six weeks ago’.

(after: Mitzka 1930: 17Mitzka 1930 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka, Walther 1930. Die Sprache der deutschen Mennoniten. Danzig: Kafemann.)

ISO Code

ISO 639-3: Low German - nds, Mennonites' Plautdietsch - pdt; Middle Low German (including the lingua franca variety of the Hanseatic League) - gml.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

- Pomorze Tylne i Prusy Zachodnie

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- Adam 1893

- Pinnow 2006b

- Sanders 1982

- Breyer 2006

- Słabig 2009

- Foss 1971

- Putzger 1905

- Zielińska 2012

- Mitzka 1954

- Müller-Baden 1905

- Höhmann i Savedra 2011

- Łopuszańska 2008b

- Jenks i Sarnowsky 2009

- Herrmann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1911

- Turnbull 2011

- Siatkowski 1983

- Holsten 1947

- Winter 1967

- Laabs 1974

- Łopuszańska 2008a

- Steinke 1914

- Laude 1995

- Schemionek 1881

- Dorr 1877

- Shakespeare 1877

- ten Venne 1998

- Debus 1996

- Reifferscheid 1887

- Teuchert 1909

- Teucher 1910

- Oppenheimer 1975

- Mitzka 1928

- Lewis 2009

- Granzow 1982

- Laskowsky i Matthias 1926

- Matthias 1933

- Riemann 1970

- König 1991

- Pinnow 2006a

- Erben 1974

- Collitz 1911

- Jellinghaus 1892

- Scheel 1894

- Vereza i Kuster 2011

- Tressmann 2009

- Lindow 1926

- Hermann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1950

- Gottsched 1736

- Mitzka 1969

- Domansky 1911

- Gotard 2009

- Bogusławski 1900

- Drosihn 1874

- Götze 1922

- Dähnert 1781

- Toby 2000

- Dollinger 1976

- Mitzka 1930

- Zacharias i Neufeld 2003

- de Graaf 2006

- Klassen 2009

- Driedger 1957

- Wiens 2009

- Johnson 1995

- Mannhardt i Thiessen 2007

- Nieuweboer 2000

- Epp 1987

- Wiens 1957

- Moelleken 1987

- Neff 1953

- Mitzka 1955

- Jarczak 1972

- Rykała 2011

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- reklama restauracji w gwarze gdańskiej

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 1

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 2

- Gwary germańskie płn. Polski XX w

- Przesunięcie granicy odmian w Poznańskiem

- Prowincja Posen w 1849 r.

- Nowa Marchia

- Dialekty germańskie Prus

- Lokalizacja wsi menonickich w Prusach ok. 1800 r.

- Młyn w okolicach Wikrowa

- Świątynia menonicka w Elblągu

- Dialekty d.niemieckich w granicach Polski

- Mapa dialektów niemieckich - 1900

- Odmiany językowe na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska

- Odmiany językowe na południowy zachód od Gdańska

- Tekst dolnoniemiecki szryftem gotyckim

- Słownik Dähnerta

- Dom podcieniowy w Steblewie

- Mapa zasięgu językowego Hanzy

- Egzemplarz Barther Bibel

- Biblia z Schottland