Low German

Standardisation

In the area of present day Poland where Low German was spoken, there were no attempts made to standardize the spoken language. Even in an early period, when Low German was used for official purposes, there was no unified standard, and idiolects of individual scribes varied to a great extent (ten Venne 1998 ten Venne 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

ten Venne 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / ten Venne, Ingmar 1998. „Stadtsprache oder Stadtsprachen: Zur Sprachlichkeit Danzigs im spätern Mittelalter”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 121: 59-84.

). However, in the 19th century, at the time of the first attempts at standardization of Low German as a whole, some of the local writers, who wrote in Low German, adapted elements from the standards tested at that time.

). However, in the 19th century, at the time of the first attempts at standardization of Low German as a whole, some of the local writers, who wrote in Low German, adapted elements from the standards tested at that time.In 1852, Klaus Groth from Dithmarschen district (in Schleswig-Holstein) published a collection of poems, Quickborn. Its popularity, together with overseas publications, contributed to a rise in the status of Low German, and because of that, attempts at standardisation became more frequent. Constant Jacob Hansen, a Flemish writer who worked in the second half of the 19th century, promoted the ideology of one Low German language which would include Dutch. Hansen (1833-1910) proposed a new, common orthography Altdietschen Spelling (Altdietschen Schrijfwijze) (Debus 1996: 24-25

Debus 1996 / komentarz/comment/r /

Debus 1996 / komentarz/comment/r / Debus, Friedhelm 1996. Von Dünkirchen bis Königsberg. Ansätze und Versuche zur Bildung einer niederdeutschen Einheitssprache. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

).

).Presently, there is no homogenous, generally accepted standard for Low German.

Dictionaries

Pomerania

As described by Reifferschied (1887 Reifferscheid 1887 / komentarz/comment/r /

Reifferscheid 1887 / komentarz/comment/r / Reifferscheid, Alexander 1887. „Über Pommerns Anteil an der niederdeutschen Sprachforschung”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 13: 33-42.

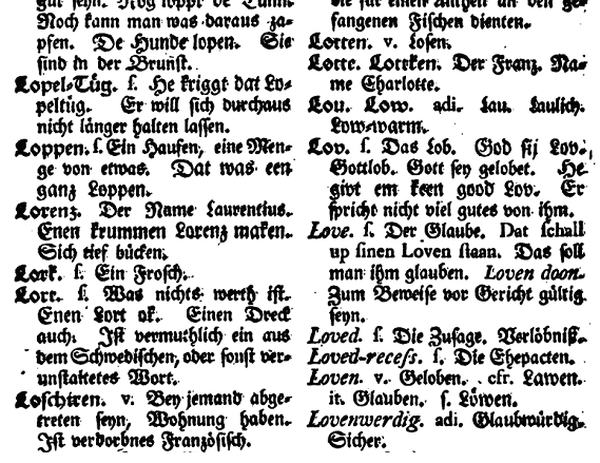

), in the first half of the 18th century J. E. Müller was collecting words and expressions from the areas around Kołobrzeg (Ger. Kolberg), and the outcome of his work was published in the third volume of Pommersche Bibliothek. In 1781, Johann Carl Dähnert published Plattdeutsches Wörterbuch nach der alten und neuen Pomerschen und Rügischen Mundart (Dictionary Of Low German On The Basis Of The Old And New Dialect of Pomerania and Rügen). During 22 years of his ordained ministry, priest Christian Wilhelm Haken (1723-1791) collected a considerable amount of vocabulary from Farther Pomerania, especially from the area between Kamień Pomorski (Cammin in Pommern) and Darłowo (Rügenwalde). Unfortunately, the manuscript of his work is lost.

), in the first half of the 18th century J. E. Müller was collecting words and expressions from the areas around Kołobrzeg (Ger. Kolberg), and the outcome of his work was published in the third volume of Pommersche Bibliothek. In 1781, Johann Carl Dähnert published Plattdeutsches Wörterbuch nach der alten und neuen Pomerschen und Rügischen Mundart (Dictionary Of Low German On The Basis Of The Old And New Dialect of Pomerania and Rügen). During 22 years of his ordained ministry, priest Christian Wilhelm Haken (1723-1791) collected a considerable amount of vocabulary from Farther Pomerania, especially from the area between Kamień Pomorski (Cammin in Pommern) and Darłowo (Rügenwalde). Unfortunately, the manuscript of his work is lost.

Illustration: Dähnert’s dictionary (1781

Dähnert 1781 / komentarz/comment/r /

Dähnert 1781 / komentarz/comment/r / Dähnert, Johann C. 1781. Platt-Deutsches Wörterbuch nach der alten und neuen Pommerschen und Rügischen Mundart. Stralsund: Struck.

).

).Works on a Pomeranian dictionary, initiated by Wolfgang Stammler, started before World War II. They were completed between 1997 and 2005 by Renate Herrmann-Winter, and published as Pommersches Wörterbuch.

In 1993, Hinterpommersches Wörterbuch der Mundart von Gross Garde (Kreis Stolp) was published. It was a dictionary of dialect spoken by citizens of Gradna Wielka (Ger. Gross Garde, in the present day Słupsk district), with Hans-Friedrich Rosenfeld as its author. It was written on the basis of data collected by Franz Jost.

In 1995, Robert Laude published a dictionary of the dialect of Further Pomerania (35,000 entries) spoken in the estuary of Parsęta River, in the area of Białogard (Ger. Belgard). It was titled Hinterpommersches Wörterbuch des Persantegebietes. In Brazil, efforts are underway in order to standardize the Pomeranian language that is used in education (Höhmann and Savedra 2011

Höhmann i Savedra 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Höhmann i Savedra 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Höhmann, Beate & Mônica M. G. Savedra 2011. „Das Pommerische in Espírito Santo: ergebnisse und perspektiven einer soziolinguistischen studie”, Pandaemonium Germanicum 18. [http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1982-88372011000200014&lng=en&nrm=iso]

). In 2006, Pomeranian-Brazilian dictionary (Dicionário Enciclopédico Pomerano-Português. Pomerisch Portugijsisch Wöirbauk) was published, with Tressmann as an author.

). In 2006, Pomeranian-Brazilian dictionary (Dicionário Enciclopédico Pomerano-Português. Pomerisch Portugijsisch Wöirbauk) was published, with Tressmann as an author.Prussia

In 1881, August Schemionek published Ausdrücke und Redensarten der Elbingschen Mundart (Expressions and Phrases of Elbląg Dialect), a minor dictionary of Elbląg dialect.In 1883, Hermann Frischbier published a dictionary of regionalisms of West- and East Prussian, Preussisches Wörterbuch.

In their article “Westpreussische Spracheigenheiten” (“West Prussian Linguistic Features”) from 1895, H. Jacob i W. Schröer provided a glossary of Low- and High German phrases from the areas of Danzig and West Prussia.

In 2005 in Kiel (Ger. Kiel), works on a six volume dictionary Preußisches Wörterbuch that had started before World War II, were completed. The dictionary contains 100,000 entries on 3600 pages. The material includes dialectal vocabulary from different dialects, both Low German and High German, collected in the area of Prussia.

In 2009, a dictionary of danziger missingsch by Paweł Fularczyk (edited by Grażyna Łopuszańska) was published.

New Marche

Excerpts from a New Marchian dictionary were published in parts by Hermann Teuchert in Zeitschrift für Deutsche Mundarten (e.g. Teuchert 1909 Teuchert 1909 / komentarz/comment/r /

Teuchert 1909 / komentarz/comment/r / Teuchert, Hermann 1909. „Aus dem neumärkischen Wortschatze”, Zeitschrift für deutsche Mundarten 4: 55-87, 118-169.

; Teucher 1910

; Teucher 1910 Teucher 1910 / komentarz/comment/r /

Teucher 1910 / komentarz/comment/r / Teuchert, Hermann 1910. „Aus dem neumärkischen Wortschatze”, Zeitschrift für deutsche Mundarten 5: 3-47.

).

).In 1994, Hans Hühnerfuß published a dictionary of High German and New Marchian as a self-publication.

Low German variations which occur in the areas of the present day Poland also appeared in general Low German dictionaries, e.g. Der Sprachschatz der Sassen (The Treasury of Saxon Language) by Heinrich Berghaus.

Other languages and variations used by the speakers on the daily basis

In early Medieval Ages, before a next German colonization had begun, Slavic Pomeranian (Ger. Pomeranisch) language was used in Pomerania (whose area had been much smaller before the name started to refer to the lands further to the West, including Rügen); it was closely related to Polish. According to the supporters of the so-called Lechitic languages theory, Kashubian language used in Pomerelia is the remainder of Pomeranian (compare: Herrmann-Winter 1995: 174 Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

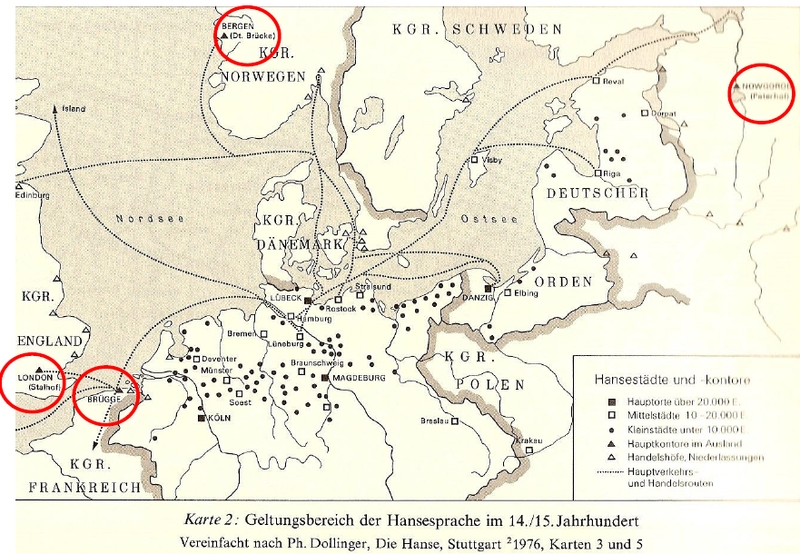

).In the 12th century, Latin started to be used in Pomerelia, and for a century and a half it was the only written language of the area. At the beginning of the 14th century, Low German started to be used as a bureaucratic language, competing with Latin in this field. At that time, the majority of common people spoke Slavic Pomeranian. Office Low German was different from local dialects. It started developing in the 13th century because of its usage by the Hanseatic League – a league of merchants from Northern German cities, with features of a sea state (Sanders 1982: 130

Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Sanders, Willy 1982. Sachsensprache. Hansesprache. Plattdeutsch. Göttingen: Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht.

; Oppenheimer 1975: 61

; Oppenheimer 1975: 61 Oppenheimer 1975 / komentarz/comment/r /

Oppenheimer 1975 / komentarz/comment/r / Oppenheimer, Franz 1975. The State. Montréal: Black Rose Books.

). After the Hanseatic League ceased to exist in the 17th century, a bloom in writing in Low German stopped as well (Sanders 1982: 126

). After the Hanseatic League ceased to exist in the 17th century, a bloom in writing in Low German stopped as well (Sanders 1982: 126 Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sanders 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Sanders, Willy 1982. Sachsensprache. Hansesprache. Plattdeutsch. Göttingen: Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht.

).

).

Illustration: Map of the linguistic scope of the Hanseatic League in 14th/15th century (after: Dollinger 1976

Dollinger 1976 / komentarz/comment/r /

Dollinger 1976 / komentarz/comment/r / Dollinger, Philippe 1976. Die Hanse. Stuttgart: Kröner.

).

).A transfer to High German as a new bureaucratic language began during the reign of Bogislaw X (ruled: 1447-1523), but as late as in 1690, ecclesiastical regulations in Szczecin were issued in a bilingual version: High German and Pomeranian Low German (in Greifswald and Stralsund in 1731) (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 172-173

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).On the other hand, Slavic Pomeranian language survived long after Germanization of the ruling class in Pommern had been completed. In 1545 and 1546, ecclesiastical synods in Słupsk and Szczecin recognized a necessity of teaching Slavic language to ministers in some areas. At the end of the 16th century, this was relevant to the following districts: Słupsk, Sławno, Bytów, Lębork, and Szczecinek. According to Herrmann-Winter, the inhabitants of those areas were tri- or quadrilingual: apart from Slavic Pomeranian, Polish and Low German, they also used High German (with local influences) (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 172-175

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).In the 18th century, mixed dialect (of Low and High German) was used in Pomerania; in 1739, it was dubbed Kuderwendisch by a minister and scholar from Pomerania, Johann David Jähncke. Linguistic influence of High German was a reason why inhabitants from different parts of Pomerania did not understand each other’s Low German dialects. In the 18th century, Low German best resisted High German influences in Farther Pomerania. The further to the North-East, the easier it was to encounter the Pomeranian language “like a fat, swaying goose from Darłowo” (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 177

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).In the mid-18th century, colonies in Pomerania were established in Coccejendorf (Radosław) and Wilhelmine (Wilkowice), and they were inhabited mainly by emigrants from Electoral Palatinate. The emigrants spoke the Palatinate (Pfälzisch) dialect of High German (Herrmann-Winter 1995: 183

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Herrmann-Winter 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Herrmann-Winter, Renate 1995. „Sprachen und Sprechen in Pommern”, Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 118: 165-187.

).

).In the mid-18th century, German, Polish and Kashubian were spoken in Danzig. In the Academic Gymnasium of City of Danzig, High German, Polish and Latin was spoken (Łopuszańska 2008a: 185

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r /

Łopuszańska 2008a / komentarz/comment/r / Łopuszańska, Grażyna 2008a. „Danziger Stadtsprache”, w: Marek Nekula & Verena Bauer & Albrecht Greule (red.) Deutsch in multilingualen Stadtzentren Mittel- und Osteuropas. Wien: Praesens-Verl.

). Kashubian was used by Low German speakers from the areas around Danzig almost until the outbreak of World War II (both languages were spoken by both Kashubians and Germans (Mitzka 1928: 22

). Kashubian was used by Low German speakers from the areas around Danzig almost until the outbreak of World War II (both languages were spoken by both Kashubians and Germans (Mitzka 1928: 22 Mitzka 1928 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1928 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1928. Sprachausgleich in den deutschen Mundarten bei Danzig. Königsberg: Gräfe und Unzer.

).

).In the Middle Ages, apart from German dialects, Latin and Polish, Baltic Old Prussian was used as well on the lands owned by the Teutonic Order (Ziesemer 1911: 131

Ziesemer 1911 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ziesemer 1911 / komentarz/comment/r / Ziesemer, Walther 1911. „Geistiges Leben im Deutschen Orden”, Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 71/73: 129-139.

). In 1228, the papal legate Wilhelm von Modena translated Latin grammar into this language.

). In 1228, the papal legate Wilhelm von Modena translated Latin grammar into this language.Contemporary speakers of Low German varieties additionally use various languages of their surroundings on the daily basis, e.g. German in Germany, Portuguese in Brazil (Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).In Polish dialects of Warmia, which remained in close contact with Low German, one can find loanwords like e.g. tyna ‘barrel’ – from LGer. tîne; brutka ‘fiancée’ – from LGer. brūt; talka ‘reel’ (a tool to measure and roll threads) – from LGer. Tall ‘a measure of yarn’ (Siatkowski 1983: 112-113

Siatkowski 1983 / komentarz/comment/r /

Siatkowski 1983 / komentarz/comment/r / Siatkowski, Janusz 1983. „Interferencje językowe na Warmii i Mazurach”, Studia z Filologii Polskiej i Słowiańskiej XXI: 103-115.

). The layer of Low German loanwords in Kashubian is of the same thickness (Toby 2000

). The layer of Low German loanwords in Kashubian is of the same thickness (Toby 2000 Toby 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Toby 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Toby, Hanna 2000. “On the Low German influences on Kashubian dialects”, Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics (Languages in Contact) 28: 329-334.

).

).

ISO Code

ISO 639-3: Low German - nds, Mennonites' Plautdietsch - pdt; Middle Low German (including the lingua franca variety of the Hanseatic League) - gml.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - NDS.

ISO-639-2: nds.

SIL (14th ed. of The Ethnologue): sxn; presently The Ethnologue uses nds.

The Linguascale (classification developed by L’Observatoire Linguistique) uses several codes for the German varieties used in the past in the present territory of Poland:

- 52-ACB-cg (New-Marchian, Pomeranian from the region of Stettin/Szczecin),

- 52-ACB-ch (most of Pomerania and Prussia),

- 52-ACB-cia (the fragment of Prussia most to the east).

Moreover, the language varieties of the German diaspora:

- 52-ACB-hd (Plautdietsch of Mennonites),

- 52-ACB-hpa (the variety from Esprito Santo, Brazil).

- Pomorze Tylne i Prusy Zachodnie

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- Adam 1893

- Pinnow 2006b

- Sanders 1982

- Breyer 2006

- Słabig 2009

- Foss 1971

- Putzger 1905

- Zielińska 2012

- Mitzka 1954

- Müller-Baden 1905

- Höhmann i Savedra 2011

- Łopuszańska 2008b

- Jenks i Sarnowsky 2009

- Herrmann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1911

- Turnbull 2011

- Siatkowski 1983

- Holsten 1947

- Winter 1967

- Laabs 1974

- Łopuszańska 2008a

- Steinke 1914

- Laude 1995

- Schemionek 1881

- Dorr 1877

- Shakespeare 1877

- ten Venne 1998

- Debus 1996

- Reifferscheid 1887

- Teuchert 1909

- Teucher 1910

- Oppenheimer 1975

- Mitzka 1928

- Lewis 2009

- Granzow 1982

- Laskowsky i Matthias 1926

- Matthias 1933

- Riemann 1970

- König 1991

- Pinnow 2006a

- Erben 1974

- Collitz 1911

- Jellinghaus 1892

- Scheel 1894

- Vereza i Kuster 2011

- Tressmann 2009

- Lindow 1926

- Hermann-Winter 1995

- Ziesemer 1950

- Gottsched 1736

- Mitzka 1969

- Domansky 1911

- Gotard 2009

- Bogusławski 1900

- Drosihn 1874

- Götze 1922

- Dähnert 1781

- Toby 2000

- Dollinger 1976

- Mitzka 1930

- Zacharias i Neufeld 2003

- de Graaf 2006

- Klassen 2009

- Driedger 1957

- Wiens 2009

- Johnson 1995

- Mannhardt i Thiessen 2007

- Nieuweboer 2000

- Epp 1987

- Wiens 1957

- Moelleken 1987

- Neff 1953

- Mitzka 1955

- Jarczak 1972

- Rykała 2011

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- reklama restauracji w gwarze gdańskiej

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 1

- plattdeutsch w Meklemburgii 2

- Gwary germańskie płn. Polski XX w

- Przesunięcie granicy odmian w Poznańskiem

- Prowincja Posen w 1849 r.

- Nowa Marchia

- Dialekty germańskie Prus

- Lokalizacja wsi menonickich w Prusach ok. 1800 r.

- Młyn w okolicach Wikrowa

- Świątynia menonicka w Elblągu

- Dialekty d.niemieckich w granicach Polski

- Mapa dialektów niemieckich - 1900

- Odmiany językowe na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska

- Odmiany językowe na południowy zachód od Gdańska

- Tekst dolnoniemiecki szryftem gotyckim

- Słownik Dähnerta

- Dom podcieniowy w Steblewie

- Mapa zasięgu językowego Hanzy

- Egzemplarz Barther Bibel

- Biblia z Schottland