Oravian dialect (Polish-Slovak continuum)

Language name

pl. gwara orawska/gwary orawskie

sk. oravske nárečie [sg]/oravské náreči [pl]

cz. oravské nářečí [sg]/oravské nářečí [pl]

en. Oravian dialect/s [sg/pl]

ger. Mundart der Region Orava [sg]/Mundarten der Region Orava [pl]

A person who speaks Oravian dialect is called “Orawianin” (Polish name) or “Orawiec” (Oravian/Podhale name).

pl. Góral, sk. Goral, Horal, Highlander - Gural

The name Orava (sk./cs. Orava, lat. Arva, hu. Árva, de. Arwa), similarly to other names in these lands, may be of Celtic origin (Ładygin 1985: 11 Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

) and it comes from the river from which also the whole region took its name. The etymology has not been fully analysed. According to one of the theories, the name corresponds to a “murmuring river” and the justification of it is to be found in the word-formation of Old Slavic dialects (Ładygin 1985: 11

) and it comes from the river from which also the whole region took its name. The etymology has not been fully analysed. According to one of the theories, the name corresponds to a “murmuring river” and the justification of it is to be found in the word-formation of Old Slavic dialects (Ładygin 1985: 11 Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

).

).

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

).

Polish Orava is located at the foot of the mountain called Babia Góra and it constitutes only a small, north-eastern part of the whole Orava region (in the Czarna Orawa basin). It is situated between the state border with Slovakia in the west and south, the aforementioned watershed of the Dunajec and Orawa rivers (the west part of Podhale) in the east and Babia Góra mountain range and the watershed between Skawa and Orawa rivers in the north.

).

Polish Orava is located at the foot of the mountain called Babia Góra and it constitutes only a small, north-eastern part of the whole Orava region (in the Czarna Orawa basin). It is situated between the state border with Slovakia in the west and south, the aforementioned watershed of the Dunajec and Orawa rivers (the west part of Podhale) in the east and Babia Góra mountain range and the watershed between Skawa and Orawa rivers in the north.

Polish Orava includes two communes: Jabłonka (villages: Jabłonka, Chyżne, Lipnica Mała, Orawka, Podwilk, Zubrzyca Dolna, Zubrzyca Górna) and Lipnica Wielka (villages: Lipnica Wielka and Kiczory), three villages in Raba Wyżna commune (Podsarnie, Harkabuz and Bukowina Osiedle) and two villages in Czarny Dunajec commune (Piekielnik and Podszkle).

According to his bibliography Ładygin (1985: 7 Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

), Orava is divided into two parts – Upper – at the foot of Pilska and Babia Góra mountains and Lower – situated north of the line defined by Trzciana (sk. Trstená), Twardoszyn (sk. Tvrdošín) and Magura Orawska.

), Orava is divided into two parts – Upper – at the foot of Pilska and Babia Góra mountains and Lower – situated north of the line defined by Trzciana (sk. Trstená), Twardoszyn (sk. Tvrdošín) and Magura Orawska.

Current Orava localization (division into Polish and Slovak part).

(map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, #JS#based on: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Slovakia_Orava.gif).

Numerous findings in the Slovak Orava region, such as burgwalls and burial grounds, can be dated back to the Bronze Age and early Iron Age. The settlement of the Orava valley was a result of population explosion which was taking place in Europe at that time. A permanent settlement in Orava existed at the most until the 4th century A.D. There is no evidence for the presence of a population in this region in the Migration Period and in the early Middle Ages. However there are signs that it was inhabited again in the late Middle Ages.

Historically, Orava was always on the border of Polish and Hungarian culture. King Stephen I of Hungary, who reigned in times of Bolesław Chrobry, tried to create a strong country and among other things, he divided his country into so called Counties of Hungary (żupy) that were managed by Komeses (żupani) who were designated by the king. Orava county was created as one of the last counties and it was colonized in accordance with Wallachian laws (it basically means that forests were leased to settlers for many years and they had a right to choose their own self-government that was represented by a knez). As a royal property, Orava belonged to the group of so called forest counties with its capitol in Zwoleń (sk. Zvolen) and only in the 13th century, when it became the private property of the Balass family, it started separating from Hungary. At that time Orava Castle (sk. Oravskýhrad) was constructed. In the 14th century, the land was bought back by the king. The army of Casimir IV Jagiellon marched through Orava which was possible because Piotr Komorowski, the owner of Orava Castle designated by the Hungarian prince, was sympathetic towards the Polish king. However, the expedition was not successful and Komorowski lost the castle for his deeds.

Orava County as a part of Kingdom of Hungary.

Copyright under Creative Commons/GNU http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Arva.png

When a part of Hungary became autonomous under Turkish supervision, the Thurzo family gained interest in this region. In 1556 Orava was bought for 18 338 250 Hungarian golden coins and the former bishop of Nitra Region, Franciszek Thurzo, became a żupan in Orava. However, it was granted to his family later, on the order of Emperor Rudolf in 1606. This family began an intensive colonisation of the region, taking advantage of shepherd migration and peasants running away from war-torn Poland. Despite arguments with the Plahty family, who officially owned the land, which resulted in forays and burning down villages, the region was peaceful up until the 17th century. At that time Jerzy Thurzo converted to Protestantism. This resulted in the persecution of the peasants who remained Roman Catholic. The counter-reformation also swept through the region. It was led by the priest Jan Szczechowicz from Ratułow. This period ended in 1659 when Habsburgs supported counter-reformation and people persecuting Catholics were prosecuted. The second part of the century was also difficult for the inhabitants of the Orava region. The Lithuanian army, led by Marshal Sapieha, marched through these lands on their way to Vienna. News about the Hungarian uprisings of Thőkőly and Rakoczy also reached Orava. Both armies plundered and robbed villages that were already in a difficult situation.

During the Partitions of Poland in the 19th century, Poland was not interested in Polish inhabitants of Orava. Highlanders from Orava region alternatively underwent Magyar and Slovak rule and as a result they lost their links with their homeland. Andrzej Kucharski, a philologist and ethnographer, was the first one to notice them. In a letter written to his friend Andrzej Jelinek, after his return (in 1828) from a five-year trip to Slovakia, he writes: “From the capital of the Orava region I went to the Beskidy Mountains (…) and after passing by the mixture of Slovak and Polish dialects, or Mazurian, as Polush Highlanders call it, I emerged on the other side of the Beskidy Mountains…”. He did not understand the origin of the dialect. The most interesting publications from the period before World War II are: Orawa by Ludwik Zejszner (1853), the cycle Polacy na Węgrzech by Maksymilian Gumplowicz (1900-19003), Orawa i jej lidność polska by Grzegorz Smólski (1910) and memories of Józef Zawiliński Z kresów polszczyzny (1912). The Polish dialect in the region of the Upper Hungary, as it was the name for Slovakia at that time, was also noticed by Czech scholars: Alois Vojtěch Sembera (1376) and Jiří Polívka (1885).

These and other publications evoked vivid interest in the matter of Poles in Hungary. The first Polish national activists emerged in the region of Orava: Julian Teisseyre, Jan Bednarski, ks. Ferdynand Machay, Eugeniusz Styrcula, Piotr Borowy, Aleksander Matonóg, ks. Marcin Sikora. When in 1918, simultaneously with the fall of Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Poland appeared on maps again and Slovakia, that was joined with Czech Republic, became a country for the first time. Soon, Rada Narodowa Polanków na Górnej Orawie (“The National Council of the Polish in the Upper Orava”) was created (6th November 1918). The group demanded that these lands should be incorporated into Poland. At the same time the Polish army marched into Spiš but had to retreat after the defeat in the battle of Kieżmark (sk. Kežmarok) on the 7th December. The national division was quite symmetrical – the Polish population lived in the region of Upper Orava, and Slovak in Lower Orava. Diplomatic arguments concerning the sovereignty of the Polish Southern frontier in the Spiš and Orava regions lasted another six years. Between 1918 and 1919, the situation became tense and there was a risk of bloodshed, but eventually an agreement on the line of demarcation was reached.

Galicia before World War I. The pink line separating Poland from Slovakia. Polish (and Ukrainian) names.

Lack of information about copyright means this image is subject to the standard principles of protection. http://donhoward.net/genpoland/gal.htm

At the same time, social warfare efforts were initialised in the country in October 1918 by Towarzystwo Tatrzańskie (“Tatra Society”), which was created by Komisja Spisko-Orawska (Spiš-Oravian Committee”) and its aim was to avail Polish society of valid publications on their rights to these lands. Later on, Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer created Komitet Spisko-Orawski in Warsaw, which joined its forces with a similar organization from Krakow and transformed it into Komitet Narodowy do Obrony Spisza, Orawy, Czacy i Podhala (“National Committee for the defence of Spiš, Orava, Czadca and Podhale”).

In the spring 1919 during an assembly in Zakopane, prof. Władysław Szajnocha was elected as a chairman. Some well-known figures were helping the board with their work: Kazmieirz Przerwa-Tetmajer, Stefan Żeromski, col. Andrzej Galica, Walery Goetel, prof. Władysław Semkowicz.

However, the matters of Spiš and Orava were disputed internationally. Under the leadership of Fr. Machay a delegation of highlanders from Spiš and Orava, Piotr Borowy from Rabczyce and Wojciech Halczyn from Lendak, came to Paris and they were granted an audience with the President of the United States of America – Thomas Woodrow Wilson. Because they could not reach an agreement, Rada Najwyższa supported the Polish suggestion that a plebiscite should be organised. Eventually, on the 20th of January delegations from France, England, Italy and Japan came to Cieszyn, which was chosen for the headquarters of the commission that was to supervise the plebiscite. The same year, at the end of winter, a unit of eighty French Alpine Infantry came to Jabłonki. The Polish situation became difficult and as a result Polish army had to withdraw to what was once the border between Hungary and Galicia. Additionally, the Czech army was stationed in each village of the Upper Orava region and a temporary administrative authority was given to the Czech.

In 1920 the situation of Poland was even more difficult as, during the Polish-Bolshevik war, the Soviet army broke the defence and marched into Warsaw. Polish diplomats had to focus on this problem. At the same time, Czechoslovakia’s position in Europe grew stronger. As a result of these events, on the 10th of July 1920, an agreement was reached in Spa (Belgium) that the Conference of Ambassadors should settle a dispute concerning the border. Some 13 days later, Polish was granted part of Spiš and Orava. 15 thousand Polish people from Orava and 25 thousand from Spiš were left on the Czechoslovak side of the border. Some estimate that even 123 thousand Poles were left in Czechoslovakia (Skawiński 2009 Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński, Marek 2009. Polacy na Słowacji. URL: http://www.polskiekresy.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=161:polacy-na-slowacji2&catid=109:etnografia&Itemid=509 [dostęp:26.09.2012 r.]

, on the basis of the reconstruction of population inhabiting this region by: Skawiński 1998

, on the basis of the reconstruction of population inhabiting this region by: Skawiński 1998 Skawiński 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński, Marek 1998. Polska mniejszość narodowa na Słowacji do 1914 roku. Praca magisterska pod kierunkiem prof. A. Jelonka. Kraków: w Zbiorach Archiwalnych Muzeum Tatrzańskiego [MT-ZA].

). Right after that, the Polish administration took over granted lands, on which the following places were situated: Jabłonka (sk. Jablonka), Górna i Dolna Zubrzyca (Vyšná – Nižná Zubrica), Orawka (Oravka), Podwilk (Podvylk) Podsarnie (Sŕnie), Harkabuz (Harkabúz), Bukowina-Podszkle (Podškle), Piekielnik (Pekelník), Chyżne (Chyžné), Lipnica Górna (Mała – Nižná Lipnica), part of Lipnica Dolna (Dolná Lipnica) as well as Głodówka i Sucha Góra wicks (Suchá Hora).

As none of the countries was satisfied with the new borders, negotiations were conducted and in 1924 both parties signed so called ‘Krakovian protocols’. As a result, Głodówka and Sucha Góra were given up for the remaining part of Lipnica Wielka.

). Right after that, the Polish administration took over granted lands, on which the following places were situated: Jabłonka (sk. Jablonka), Górna i Dolna Zubrzyca (Vyšná – Nižná Zubrica), Orawka (Oravka), Podwilk (Podvylk) Podsarnie (Sŕnie), Harkabuz (Harkabúz), Bukowina-Podszkle (Podškle), Piekielnik (Pekelník), Chyżne (Chyžné), Lipnica Górna (Mała – Nižná Lipnica), part of Lipnica Dolna (Dolná Lipnica) as well as Głodówka i Sucha Góra wicks (Suchá Hora).

As none of the countries was satisfied with the new borders, negotiations were conducted and in 1924 both parties signed so called ‘Krakovian protocols’. As a result, Głodówka and Sucha Góra were given up for the remaining part of Lipnica Wielka.

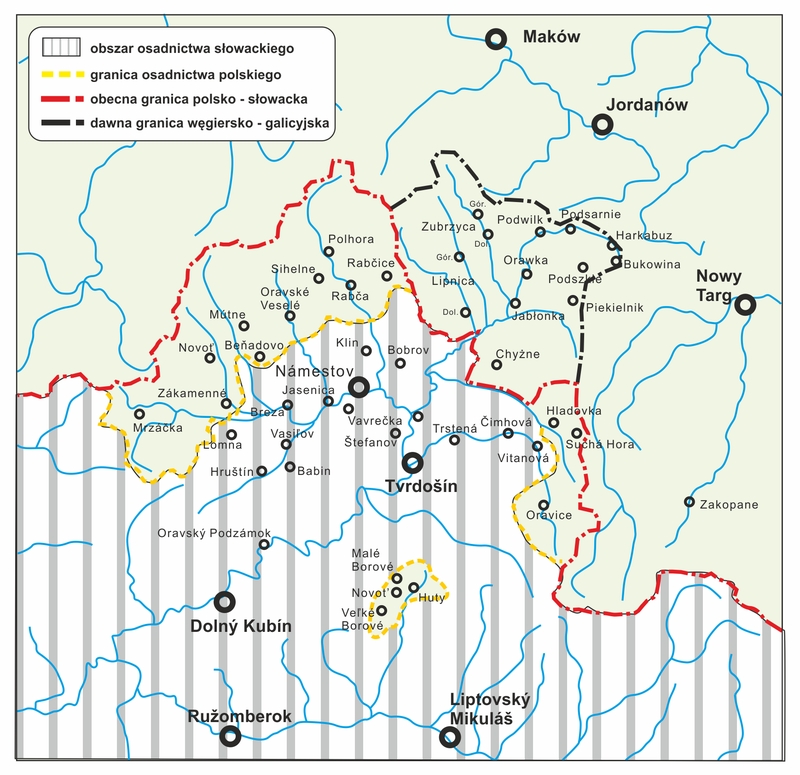

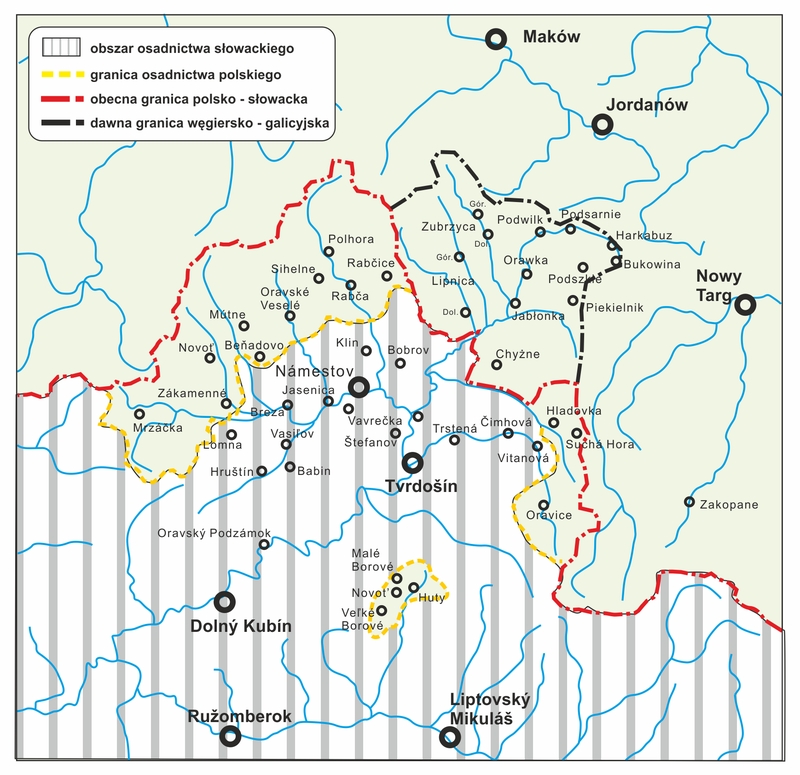

Nationalities in the Orava region in 1931 according to “Ziemia” newspaper.

(map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, #JS#based on: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Orawa_1938.jpg)

In 1938 the Polish Government, taking advantage of Czechoslovak weakness after the Munich Agreement, asked Prague to give up four small parts of Orava, namely the villages given to Czechoslovakia by Poland in 1924 (Sucha Góra, Głodówka), part of Trzciana commune neighbouring with Lipnica Wielka village (Krywań forest/ sk. Kriváň, pasture and Osadzka forest), part of Bobór territory (Bobrov – part of the Western slope of Krywań mountain) and Orawska Półgóra/Polhora (Dolina Jałowca from przełęcz Głuchaczka to przełęcz Jałowiecka with uroczysko Jałowiec and the Souther slope of Mędralowa (Modrálová) mountain. The new border was defined by Półgórzanka/Polhoranka stream. This change was determined by the Polish tourist trail that before the correction, similarly as nowadays, led towards Babia Góra mountain through Czechoslovak territory. These terrains belonged to Poland for less than a year as after the outbreak of World War II Slovakia regained them.

During the Hitler occupation, the Upper Orava belonged to the fascist Slovakia of Fr. Tiso according to the agreement of the 21st of November 1939. When the war began, the Slovak war minister, gen. Ferdynand Čatloš, gave the Slovak army the order to take over Polish Podtatrze and Orava. However, the sabotage group led mainly by Andrzej Pilch counteracted Slovak actions successfully. In January 1945, the Red Army marched into Poland and broke German defence after 9 weeks. The same year the border from before 1938 was restored and the region was divided between Czechoslovakia and Poland once again (Ładygin 1985: 11ff Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

).

).

The Orava region (without the surroundings of Mędralowa) was marked as part of Poland in 1939 on the topographic map created by WIG in 1939.

Copyright under Creative Commons/GNU http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Orawa_1938.jpg

The current border between Poland, Czech and Slovakia was defined in the agreement signed in 1958.

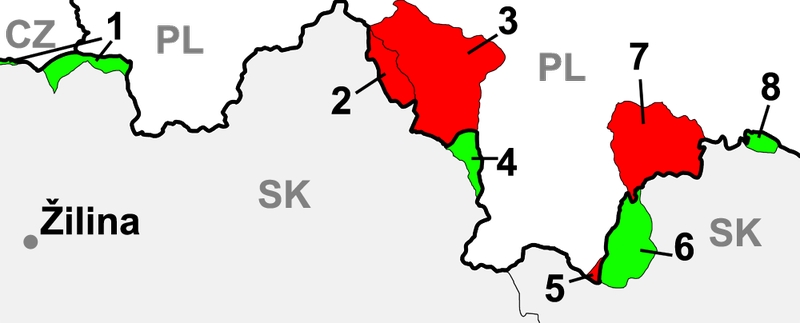

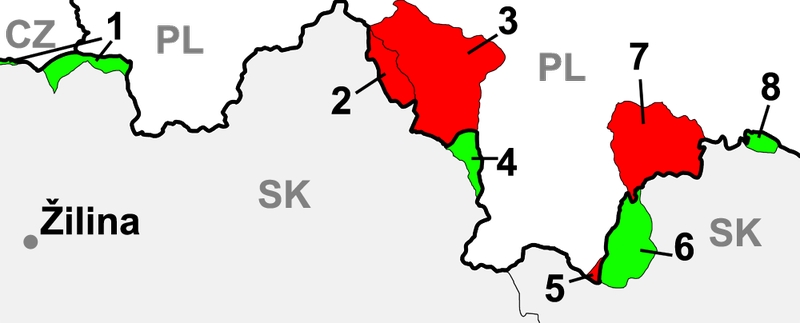

The map depicting changes in the borderline between what is today Poland and Slovakia in the first half of the 20th century. The last terrain incorporated into Poland is designated by the colour red and the last terrain joined to Slovakia is in green.

Copyright under Creative Commons/GNU http://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Datei:Slovakia_borderPoland.png

Legend

pl. gwara orawska/gwary orawskie

sk. oravske nárečie [sg]/oravské náreči [pl]

cz. oravské nářečí [sg]/oravské nářečí [pl]

en. Oravian dialect/s [sg/pl]

ger. Mundart der Region Orava [sg]/Mundarten der Region Orava [pl]

A person who speaks Oravian dialect is called “Orawianin” (Polish name) or “Orawiec” (Oravian/Podhale name).

pl. Góral, sk. Goral, Horal, Highlander - Gural

The name Orava (sk./cs. Orava, lat. Arva, hu. Árva, de. Arwa), similarly to other names in these lands, may be of Celtic origin (Ładygin 1985: 11

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r / Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

) and it comes from the river from which also the whole region took its name. The etymology has not been fully analysed. According to one of the theories, the name corresponds to a “murmuring river” and the justification of it is to be found in the word-formation of Old Slavic dialects (Ładygin 1985: 11

) and it comes from the river from which also the whole region took its name. The etymology has not been fully analysed. According to one of the theories, the name corresponds to a “murmuring river” and the justification of it is to be found in the word-formation of Old Slavic dialects (Ładygin 1985: 11 Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r / Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

).

).History and geopolitics

Localization – previously and currently in the Republic of Poland

Orava is a mountainous, historic-ethnographic land situated on the borderline of Poland and Slovakia and it spreads over approximately 1600 km2. Its border is defined by Beskid Wysoki in the north, ridges of Kisuckie Mountains and Mała Fatra in the west; Choczańskie Mountains and Western Tatra in the south; the watershed of Orawa and Dunajec Rivers that goes across Orawsko-Nowotarska Valley in the east (Ładygin 1985: 7 Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r / Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

).

Polish Orava is located at the foot of the mountain called Babia Góra and it constitutes only a small, north-eastern part of the whole Orava region (in the Czarna Orawa basin). It is situated between the state border with Slovakia in the west and south, the aforementioned watershed of the Dunajec and Orawa rivers (the west part of Podhale) in the east and Babia Góra mountain range and the watershed between Skawa and Orawa rivers in the north.

).

Polish Orava is located at the foot of the mountain called Babia Góra and it constitutes only a small, north-eastern part of the whole Orava region (in the Czarna Orawa basin). It is situated between the state border with Slovakia in the west and south, the aforementioned watershed of the Dunajec and Orawa rivers (the west part of Podhale) in the east and Babia Góra mountain range and the watershed between Skawa and Orawa rivers in the north.Polish Orava includes two communes: Jabłonka (villages: Jabłonka, Chyżne, Lipnica Mała, Orawka, Podwilk, Zubrzyca Dolna, Zubrzyca Górna) and Lipnica Wielka (villages: Lipnica Wielka and Kiczory), three villages in Raba Wyżna commune (Podsarnie, Harkabuz and Bukowina Osiedle) and two villages in Czarny Dunajec commune (Piekielnik and Podszkle).

According to his bibliography Ładygin (1985: 7

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r / Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

), Orava is divided into two parts – Upper – at the foot of Pilska and Babia Góra mountains and Lower – situated north of the line defined by Trzciana (sk. Trstená), Twardoszyn (sk. Tvrdošín) and Magura Orawska.

), Orava is divided into two parts – Upper – at the foot of Pilska and Babia Góra mountains and Lower – situated north of the line defined by Trzciana (sk. Trstená), Twardoszyn (sk. Tvrdošín) and Magura Orawska.

Current Orava localization (division into Polish and Slovak part).

(map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, #JS#based on: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Slovakia_Orava.gif).

Numerous findings in the Slovak Orava region, such as burgwalls and burial grounds, can be dated back to the Bronze Age and early Iron Age. The settlement of the Orava valley was a result of population explosion which was taking place in Europe at that time. A permanent settlement in Orava existed at the most until the 4th century A.D. There is no evidence for the presence of a population in this region in the Migration Period and in the early Middle Ages. However there are signs that it was inhabited again in the late Middle Ages.

Historically, Orava was always on the border of Polish and Hungarian culture. King Stephen I of Hungary, who reigned in times of Bolesław Chrobry, tried to create a strong country and among other things, he divided his country into so called Counties of Hungary (żupy) that were managed by Komeses (żupani) who were designated by the king. Orava county was created as one of the last counties and it was colonized in accordance with Wallachian laws (it basically means that forests were leased to settlers for many years and they had a right to choose their own self-government that was represented by a knez). As a royal property, Orava belonged to the group of so called forest counties with its capitol in Zwoleń (sk. Zvolen) and only in the 13th century, when it became the private property of the Balass family, it started separating from Hungary. At that time Orava Castle (sk. Oravskýhrad) was constructed. In the 14th century, the land was bought back by the king. The army of Casimir IV Jagiellon marched through Orava which was possible because Piotr Komorowski, the owner of Orava Castle designated by the Hungarian prince, was sympathetic towards the Polish king. However, the expedition was not successful and Komorowski lost the castle for his deeds.

Orava County as a part of Kingdom of Hungary.

Copyright under Creative Commons/GNU http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Arva.png

When a part of Hungary became autonomous under Turkish supervision, the Thurzo family gained interest in this region. In 1556 Orava was bought for 18 338 250 Hungarian golden coins and the former bishop of Nitra Region, Franciszek Thurzo, became a żupan in Orava. However, it was granted to his family later, on the order of Emperor Rudolf in 1606. This family began an intensive colonisation of the region, taking advantage of shepherd migration and peasants running away from war-torn Poland. Despite arguments with the Plahty family, who officially owned the land, which resulted in forays and burning down villages, the region was peaceful up until the 17th century. At that time Jerzy Thurzo converted to Protestantism. This resulted in the persecution of the peasants who remained Roman Catholic. The counter-reformation also swept through the region. It was led by the priest Jan Szczechowicz from Ratułow. This period ended in 1659 when Habsburgs supported counter-reformation and people persecuting Catholics were prosecuted. The second part of the century was also difficult for the inhabitants of the Orava region. The Lithuanian army, led by Marshal Sapieha, marched through these lands on their way to Vienna. News about the Hungarian uprisings of Thőkőly and Rakoczy also reached Orava. Both armies plundered and robbed villages that were already in a difficult situation.

During the Partitions of Poland in the 19th century, Poland was not interested in Polish inhabitants of Orava. Highlanders from Orava region alternatively underwent Magyar and Slovak rule and as a result they lost their links with their homeland. Andrzej Kucharski, a philologist and ethnographer, was the first one to notice them. In a letter written to his friend Andrzej Jelinek, after his return (in 1828) from a five-year trip to Slovakia, he writes: “From the capital of the Orava region I went to the Beskidy Mountains (…) and after passing by the mixture of Slovak and Polish dialects, or Mazurian, as Polush Highlanders call it, I emerged on the other side of the Beskidy Mountains…”. He did not understand the origin of the dialect. The most interesting publications from the period before World War II are: Orawa by Ludwik Zejszner (1853), the cycle Polacy na Węgrzech by Maksymilian Gumplowicz (1900-19003), Orawa i jej lidność polska by Grzegorz Smólski (1910) and memories of Józef Zawiliński Z kresów polszczyzny (1912). The Polish dialect in the region of the Upper Hungary, as it was the name for Slovakia at that time, was also noticed by Czech scholars: Alois Vojtěch Sembera (1376) and Jiří Polívka (1885).

These and other publications evoked vivid interest in the matter of Poles in Hungary. The first Polish national activists emerged in the region of Orava: Julian Teisseyre, Jan Bednarski, ks. Ferdynand Machay, Eugeniusz Styrcula, Piotr Borowy, Aleksander Matonóg, ks. Marcin Sikora. When in 1918, simultaneously with the fall of Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Poland appeared on maps again and Slovakia, that was joined with Czech Republic, became a country for the first time. Soon, Rada Narodowa Polanków na Górnej Orawie (“The National Council of the Polish in the Upper Orava”) was created (6th November 1918). The group demanded that these lands should be incorporated into Poland. At the same time the Polish army marched into Spiš but had to retreat after the defeat in the battle of Kieżmark (sk. Kežmarok) on the 7th December. The national division was quite symmetrical – the Polish population lived in the region of Upper Orava, and Slovak in Lower Orava. Diplomatic arguments concerning the sovereignty of the Polish Southern frontier in the Spiš and Orava regions lasted another six years. Between 1918 and 1919, the situation became tense and there was a risk of bloodshed, but eventually an agreement on the line of demarcation was reached.

Galicia before World War I. The pink line separating Poland from Slovakia. Polish (and Ukrainian) names.

Lack of information about copyright means this image is subject to the standard principles of protection. http://donhoward.net/genpoland/gal.htm

At the same time, social warfare efforts were initialised in the country in October 1918 by Towarzystwo Tatrzańskie (“Tatra Society”), which was created by Komisja Spisko-Orawska (Spiš-Oravian Committee”) and its aim was to avail Polish society of valid publications on their rights to these lands. Later on, Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer created Komitet Spisko-Orawski in Warsaw, which joined its forces with a similar organization from Krakow and transformed it into Komitet Narodowy do Obrony Spisza, Orawy, Czacy i Podhala (“National Committee for the defence of Spiš, Orava, Czadca and Podhale”).

In the spring 1919 during an assembly in Zakopane, prof. Władysław Szajnocha was elected as a chairman. Some well-known figures were helping the board with their work: Kazmieirz Przerwa-Tetmajer, Stefan Żeromski, col. Andrzej Galica, Walery Goetel, prof. Władysław Semkowicz.

However, the matters of Spiš and Orava were disputed internationally. Under the leadership of Fr. Machay a delegation of highlanders from Spiš and Orava, Piotr Borowy from Rabczyce and Wojciech Halczyn from Lendak, came to Paris and they were granted an audience with the President of the United States of America – Thomas Woodrow Wilson. Because they could not reach an agreement, Rada Najwyższa supported the Polish suggestion that a plebiscite should be organised. Eventually, on the 20th of January delegations from France, England, Italy and Japan came to Cieszyn, which was chosen for the headquarters of the commission that was to supervise the plebiscite. The same year, at the end of winter, a unit of eighty French Alpine Infantry came to Jabłonki. The Polish situation became difficult and as a result Polish army had to withdraw to what was once the border between Hungary and Galicia. Additionally, the Czech army was stationed in each village of the Upper Orava region and a temporary administrative authority was given to the Czech.

In 1920 the situation of Poland was even more difficult as, during the Polish-Bolshevik war, the Soviet army broke the defence and marched into Warsaw. Polish diplomats had to focus on this problem. At the same time, Czechoslovakia’s position in Europe grew stronger. As a result of these events, on the 10th of July 1920, an agreement was reached in Spa (Belgium) that the Conference of Ambassadors should settle a dispute concerning the border. Some 13 days later, Polish was granted part of Spiš and Orava. 15 thousand Polish people from Orava and 25 thousand from Spiš were left on the Czechoslovak side of the border. Some estimate that even 123 thousand Poles were left in Czechoslovakia (Skawiński 2009

Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Skawiński, Marek 2009. Polacy na Słowacji. URL: http://www.polskiekresy.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=161:polacy-na-slowacji2&catid=109:etnografia&Itemid=509 [dostęp:26.09.2012 r.]

, on the basis of the reconstruction of population inhabiting this region by: Skawiński 1998

, on the basis of the reconstruction of population inhabiting this region by: Skawiński 1998 Skawiński 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Skawiński, Marek 1998. Polska mniejszość narodowa na Słowacji do 1914 roku. Praca magisterska pod kierunkiem prof. A. Jelonka. Kraków: w Zbiorach Archiwalnych Muzeum Tatrzańskiego [MT-ZA].

). Right after that, the Polish administration took over granted lands, on which the following places were situated: Jabłonka (sk. Jablonka), Górna i Dolna Zubrzyca (Vyšná – Nižná Zubrica), Orawka (Oravka), Podwilk (Podvylk) Podsarnie (Sŕnie), Harkabuz (Harkabúz), Bukowina-Podszkle (Podškle), Piekielnik (Pekelník), Chyżne (Chyžné), Lipnica Górna (Mała – Nižná Lipnica), part of Lipnica Dolna (Dolná Lipnica) as well as Głodówka i Sucha Góra wicks (Suchá Hora).

As none of the countries was satisfied with the new borders, negotiations were conducted and in 1924 both parties signed so called ‘Krakovian protocols’. As a result, Głodówka and Sucha Góra were given up for the remaining part of Lipnica Wielka.

). Right after that, the Polish administration took over granted lands, on which the following places were situated: Jabłonka (sk. Jablonka), Górna i Dolna Zubrzyca (Vyšná – Nižná Zubrica), Orawka (Oravka), Podwilk (Podvylk) Podsarnie (Sŕnie), Harkabuz (Harkabúz), Bukowina-Podszkle (Podškle), Piekielnik (Pekelník), Chyżne (Chyžné), Lipnica Górna (Mała – Nižná Lipnica), part of Lipnica Dolna (Dolná Lipnica) as well as Głodówka i Sucha Góra wicks (Suchá Hora).

As none of the countries was satisfied with the new borders, negotiations were conducted and in 1924 both parties signed so called ‘Krakovian protocols’. As a result, Głodówka and Sucha Góra were given up for the remaining part of Lipnica Wielka.

Nationalities in the Orava region in 1931 according to “Ziemia” newspaper.

(map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, #JS#based on: http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Orawa_1938.jpg)

In 1938 the Polish Government, taking advantage of Czechoslovak weakness after the Munich Agreement, asked Prague to give up four small parts of Orava, namely the villages given to Czechoslovakia by Poland in 1924 (Sucha Góra, Głodówka), part of Trzciana commune neighbouring with Lipnica Wielka village (Krywań forest/ sk. Kriváň, pasture and Osadzka forest), part of Bobór territory (Bobrov – part of the Western slope of Krywań mountain) and Orawska Półgóra/Polhora (Dolina Jałowca from przełęcz Głuchaczka to przełęcz Jałowiecka with uroczysko Jałowiec and the Souther slope of Mędralowa (Modrálová) mountain. The new border was defined by Półgórzanka/Polhoranka stream. This change was determined by the Polish tourist trail that before the correction, similarly as nowadays, led towards Babia Góra mountain through Czechoslovak territory. These terrains belonged to Poland for less than a year as after the outbreak of World War II Slovakia regained them.

During the Hitler occupation, the Upper Orava belonged to the fascist Slovakia of Fr. Tiso according to the agreement of the 21st of November 1939. When the war began, the Slovak war minister, gen. Ferdynand Čatloš, gave the Slovak army the order to take over Polish Podtatrze and Orava. However, the sabotage group led mainly by Andrzej Pilch counteracted Slovak actions successfully. In January 1945, the Red Army marched into Poland and broke German defence after 9 weeks. The same year the border from before 1938 was restored and the region was divided between Czechoslovakia and Poland once again (Ładygin 1985: 11ff

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r /

Ładygin 1985 / komentarz/comment/r / Ładygin, Zbigniew 1985. 7 dni na Orawie polskiej. Warszawa-Kraków: Wydawnictwo Turystyczne PPTK „Kraj”. URL: http://www.rj.jawnet.pl/kpb/materialy/orawa.pdf [dostęp: 25.09.2012 r.]

).

).

The Orava region (without the surroundings of Mędralowa) was marked as part of Poland in 1939 on the topographic map created by WIG in 1939.

Copyright under Creative Commons/GNU http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Orawa_1938.jpg

The current border between Poland, Czech and Slovakia was defined in the agreement signed in 1958.

The map depicting changes in the borderline between what is today Poland and Slovakia in the first half of the 20th century. The last terrain incorporated into Poland is designated by the colour red and the last terrain joined to Slovakia is in green.

Copyright under Creative Commons/GNU http://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Datei:Slovakia_borderPoland.png

Legend

- Region of the Skalité village: 2 October 1938 r. – 21 November 1939 within Polish borders;

- Lipnica Wielka: 1918 r. – 12 March 1924 r. within Czechoslovak borders, later incorporated into Poland in exchange for the territory designated as number 4; 21 November 1939 – 20 May 1945 incorporated into Slovakia; after 1945 into Poland;

- North-eastern Orava (Jabłonki region): 1918 r. – 21 November 1939 r. within Polish borders; 21 November 1939 r. – 20 May 1945 Slovak; after 1945 Polish;

- Głodówka (sk. Hladovka) and Sucha Góra (Suchá Hora) – 1918 – 12 March 1924 within Polish borders, later incorporated to Czechoslovakia in exchange for the territory denoted as number 2; 1 December 1938 – 21 November 1939 belonged to Poland; 21 November 1939 - 20 May 1945 part of Slovakia; after 1945 Slovakian;

- Part of Rysy slope, that was under Hungarian and Galician dispute that was settler in favour of Poland in 1920; Polish territory;

- Jaworzyna Spiska: end of 1918 to 1919 within Polish borders; since 28 July 1920 – 1 December 1939 within Czechoslovak borders; 1 December 1938 – 21 November 1939 Polish, since 21 November 1939 within Slovak (Czechoslovak) borders;

- Polish Spiš: 28 July 1920 – 21 November 1939 within Polish borders; 21 November 1939 – 20 May 1945 Slovak; since 1945 Polish; 8. Leśnica: end of 1918 to 1919 within Polish borders; 28 July 1920 – 1 December 1938 within Czechoslovak borders; 1 December 1938 – 21 November 1939 Polish; since 1939 Slovak (Czechoslovak).

Localization – outside the Polish Repulic

Currently, Slovak dialects are also spoken outside the country – often in the USA, Canada, Croatian Slavonia, Bulgaria, and in many other countries.ISO Code

no code

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- Sikora 1989b

- Ładygin 1985

- Skawiński 1998

- Skawiński 2009

- Kąś 2002

- Sikora 2008

- Kryk-Kastovsky 1996

- Sikora 1989a

- Gawlasová 2012

- Kantor 1997

- Dudok D. 1993

- Dudok M. 1993

- Maxwell 2006

- Sikora 2006

- Moskal 2004

- Štolc 1968

- Zgama 2003

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Współczesna lokalizacja Orawy

- ilustr02

- ilustr03

- Narodowości na Orawie w 1931 r.

- ilustr05

- ilustr06

- Atlas slovenskeho jazyka