orawska gwara

Krótka charakterystyka typologiczna

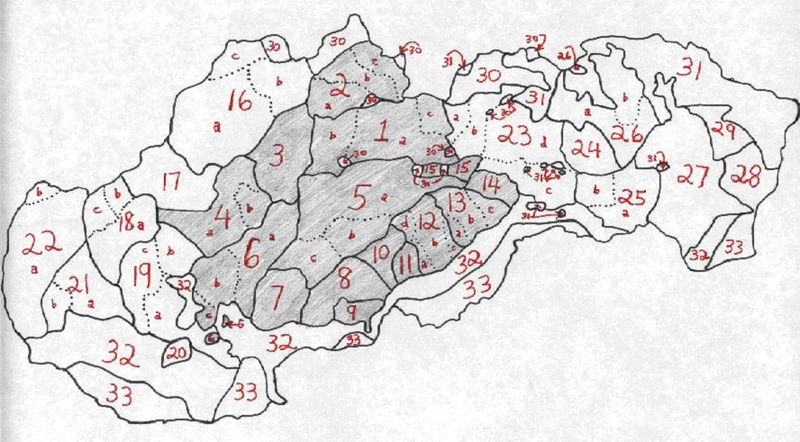

Problem z klasyfikacją gwary orawskiej polega przede wszystkim na tym, że wg polskich filologów jest to dialekt języka polskiego, a wg filologów słowackich – słowackiego. Często też mówi się o polskich i słowackich gwarach orawskich (ze względu na liczne różnice, jak wpływ polskiego języka literackiego na polską część Orawy) lub traktuje się gwarę orawską jako dialekt przejściowy. Historycznie dialekt wywodzi się z języka polskiego i poddany był wielu wpływom niegdyś węgierskim, a obecnie – słowackim. Pewnym jest natomiast, iż należy do grupy gwar góralskich.W dialektologii polskiej gwara orawska należy do dialektu małopolskiego języka polskiego. W dialektologii słowackiej gwara orawska należy do grupy północnej dialektów środkowosłowackich i dzieli się dalej na gwary: górną, centralną i dolną (na mapie oznaczone 2a–c) [9

przyp09 / komentarz/comment /

przyp09 / komentarz/comment / http://www.pitt.edu/~armata/dialects.htm [dostęp: 26.09.2012 r.]

][10

][10 przyp10 / komentarz/comment /

przyp10 / komentarz/comment / http://slovake.eu/en/intro/language/dialects [dostęp: 26.09.2012 r.]

]. Czasami wyróżnia się czwartą grupę dialektów: dolnoziemskich (słow. dolnozemské), która jest podgrupą zarówno środkowej, jak i zachodniej grupy dialektów (Štolc 1968

]. Czasami wyróżnia się czwartą grupę dialektów: dolnoziemskich (słow. dolnozemské), która jest podgrupą zarówno środkowej, jak i zachodniej grupy dialektów (Štolc 1968 Štolc 1968 / komentarz/comment/r /

Štolc 1968 / komentarz/comment/r / Štolc, J. & F. Buffa & A. Habovštiak 1968–1984. Atlas slovenskéhojazyka. T. I–IV. Bratysława: VEDA.

) i podlegała silnym wpływom językowym ze strony serbskiego, rumuńskiego i węgierskiego w wyniku długotrwałego odłączenia od terenów Słowacji (Dudok D. 1993

) i podlegała silnym wpływom językowym ze strony serbskiego, rumuńskiego i węgierskiego w wyniku długotrwałego odłączenia od terenów Słowacji (Dudok D. 1993 Dudok D. 1993 / komentarz/comment/r /

Dudok D. 1993 / komentarz/comment/r / Dudok, Daniel 1993. „Vznik a charakter slovenských nárečí v juhoslovanskej Vojvodine”, Zborník Spolku vojvodinských slovakistov 15: 19–29.

; Dudok M. 1993

; Dudok M. 1993 Dudok M. 1993 / komentarz/comment/r /

Dudok M. 1993 / komentarz/comment/r / Dudok, Miroslav 1993. „Prostriedky mikrokompozície textu v slovenčine a v srbčine”, Zborník Spolku vojvodinských slovakistov 15: 41–51.

) [11

) [11 przyp11 / komentarz/comment /

przyp11 / komentarz/comment / http://www.101languages.net/slovak/dialects.html [dostęp: 26.09.2012 r.]

]. Grupa dialektów zachodnich języka słowackiego jest na tyle zbliżona do języka czeskiego, że pozwala ich użytkownikom porozumieć się ze sobą.

]. Grupa dialektów zachodnich języka słowackiego jest na tyle zbliżona do języka czeskiego, że pozwala ich użytkownikom porozumieć się ze sobą.Wg Marka Skawińskiego przynależność gwary orawskiej do gwar polskich jest jednoznaczna – pisze on:

Nawet lokalnie mieszany, polsko-słowacki charakter gwar Górali Polskich na terenie wysp etnicznych, w niektórych wsiach doliny Poprady i zachodniej części Czadeckiego, przesądza o polskim charakterze etnicznym. Istotny jest bowiem fakt, że polską jest podstawa językowa tych gwar i cechy polskie mają charakter autochtoniczny, podczas gdy słowackie wtórny (przeważnie zresztą cechy leksykalne), w powiązaniu z faktem, że interferencje językowe polsko-słowackie na Słowacji w praktyce zachodzą wyłącznie jednokierunkowo, tzn. wpływom słowackim ulegają gwary polskie, praktycznie brak interferencji w kierunku odwrotnym zwłaszcza z terenu Polski czy Zaolzia. Powyższe przesądza o tym, że gwary mieszane lub przejściowe polsko-słowackie dowodzą polskiego pochodzenia, a przy zachowaniu ciągłości pochodzenia etnicznego (w skupiskach zwartych czy z dużym udziałem małżeństw endogamicznych w danej grupie etnicznej) o polskiej, w dalszym ciągu przynależności etnicznej mimo stopniowego zesłowaczenia językowego. Ogólnie na Słowacji, rzeczywistym odzwierciedleniem tego jest termin Goral (Skawiński 2009Świadomość filologów na temat struktury języka słowackiego zaczęła się formować dopiero w XIX w. i stopniowo się zmieniała aż do obecnego podziału na trzy główne dialekty: środkowy, wschodni i zachodni (w czasie istnienia Czechosłowacji język słowacki był przez niektórych uznawany za dialekt języka czechosłowackiego) (Maxwell 2006: 147Skawiński 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Skawiński, Marek 2009. Polacy na Słowacji. URL: http://www.polskiekresy.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=161:polacy-na-slowacji2&catid=109:etnografia&Itemid=509 [dostęp:26.09.2012 r.]).

Maxwell 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Maxwell 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Maxwell, Alexander 2006. „Why the Slovak Language Has Three Dialects: A Case Study in Historical Perceptual Dialectology”, Austrian History Yearbook 37: 141–162. URL: http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/479/article.pdf?sequence=3 [dostęp: 26.09.2012 r.]

).

).

Przerysowane przez Joe Armata z: Atlas slovenskeho jazyka, Jozef Stolc, red. Bratislava, Slovak Academy of Sciences, 1968. Brak informacji o prawach autorskich, zatem podlega standardowej ochronie.

Typologia genetyczna języka

W zależności od tego, czy traktować gwarę orawską jako dialekt języka polskiego czy słowackiego, typologia genetycznie będzie wyglądała następująco:rodzina indoeuropejska → bałtosłowiańska → słowiańska → zachodniosłowiańska → lechicka → język polski → gwara orawska

rodzina indoeuropejska → bałtosłowiańska → słowiańska → zachodniosłowiańska → czesko-słowacka → język słowacki → gwara orawska

Gwara orawska dzieli na szereg subdialektów, przeważnie związanych z konkretną wsią. Każda z takich subgwar posiada swoje unikatowe cechy – najczęściej fonologiczne, ale nierzadko także morfologiczne i leksykalne. Przykładowo, gwara wsi Orawskie Wesele (słow. Oravské Veselé) charakteryzuje się szeregiem różnic fonetycznych nie tylko w stosunku do języka słowackiego (czy polskiego), ale także względem innych gwar orawskich[12

przyp12 / komentarz/comment /

przyp12 / komentarz/comment / http://www.oravskevesele.sk/kultura/narecie [dostęp: 29.06.2013 r.]

] [13

] [13 przyp13 / komentarz/comment /

przyp13 / komentarz/comment / http://www.goralske-narecie.estranky.sk/clanky/oravske-vesele.html [dostęp: 18.05.2013]

]:

]:- labializacja samogłoski [o], przez co wymawia się ją jak [ŭo], np. vŭorač ‘orać’, kŭosыk ‘koszyk’, cŭosnok ‘czosnek’;

- w odróżnieniu od pozostałych dialektów obecna jest głoska zapisywana przez dialektologów często jako [ы] – w lingwistyce zwana tylnym zamkniętym [ẹ] – w słowackim zapisywana jako

, występująca zarówno po miękkich jak i twardych spółgłoskach, np.: vыrek ‘sowa’ (pot.), sыpula ‘strzała’, mыs ‘mysz’, rыňok ‘rynek’; - unikalny wśród dialektów słowackich poziom rozwoju samogłosek nosowych, które wymawiane są jak kombinacja spółgłoska plus samogłoska, np. gonšenica ‘gąsienica’, konsek ‘kąsek’, švjыnčič ‘święcić’;

- depalatalizacja [e] na [o/ŭo/ọ] przed spółgłoskami [r, l, n], np. kršon ‘złamany, pogwałcony’, fcŭora ‘wczoraj’, vjecọr ‘wieczór’;

- głoska [ọ] występuje w pozycji prasłowiańskiego [14

przyp14 / komentarz/comment /

przyp14 / komentarz/comment /

Język będący poprzednikiem wszystkich języków. ] [o] (w dialektach środkowosłowackich w postaci dyftongu [15

] [o] (w dialektach środkowosłowackich w postaci dyftongu [15 przyp15 / komentarz/comment /

przyp15 / komentarz/comment /

Dyftong, inaczej dwugłoska, jest to rodzaj pojedynczej samogłoski, którą ludzkie ucho słyszy jako dwa dźwięki, np. au w słowie hydraulik. ] [ŭo] lub częściej po prostu [o]) mimo wpływów języka literackiego, np. w wyrazach: nọs, vọs, thọrš, stọl;

] [ŭo] lub częściej po prostu [o]) mimo wpływów języka literackiego, np. w wyrazach: nọs, vọs, thọrš, stọl; - występowanie [ŭo] w miejscu [a], np. hlŭop ‘chłop’, glŭodnы ‘głodny’, prŭox ‘proch’;

- występowanie samogłoski [ọ] w długich sylabach inicjalnych, np. mrọs ‘mróz’, brọzda ‘bruzda’, dlọtkŭo ‘dłutko’, plọkač ‘płakać’ (wynika to przekształcenia prasłowiańskiego *tort, *tolt w trot-, tlot-) [16

przyp16 / komentarz/comment /

przyp16 / komentarz/comment /

Chodzi tu o proces zwany przestawką – czyli zamianą miejscami głosek w wyrazie – bardzo częsty w ewolucji języków słowiańskich; por.: karva → krowa; dervo → dr`evo → drzewo; melko → mleko. ];

]; - charakterystyczne [ja], w wyrazach takich jak: hovjadŭo, vjater ‘wiatr’, stavjač‘stawiać’, zarobjač ‘zarabiać’;

- zachowanie jerów [17

przyp17 / komentarz/comment /

przyp17 / komentarz/comment /

Jery to półsamogłoski powstałe w wyniku skrócenia się głosek [i] oraz [u] w języku prasłowiańskim. ] [ы] oraz [e], np. mech ‘mech’, ftŭorek ‘wtorek’, deska ‘deska’, vjonek ‘wianek’, dыsc, ľыnŭovы;

] [ы] oraz [e], np. mech ‘mech’, ftŭorek ‘wtorek’, deska ‘deska’, vjonek ‘wianek’, dыsc, ľыnŭovы; - wymawianie głoski [ř] jako dwóch spółgłosek: [rž] (po spółgłoskach dźwięcznych i na początku sylaby) oraz [rš] (po spółgłoskach bezdźwięcznych lub na końcu wyrazu), np. guari ‘gwarzyć’, drževŭo ‘drzewo’, kršыžvy ‘krzywy’, tršešňe ‘kara’, pastыrš ‘pasterz’;

- zachowanie prasłowiańskiej wymowy [g] zamiast [h], np. gvjozdы ‘gwiazdy’, gыnš ‘gęś’ (słow. hus), gorcki ‘górski’ (słow. hura ‘góra’), jego (słow. jeho);

- zachowanie mazurzenia – wymawiania [c, s, z] zamiast [č, š, ž], np. cuč ‘czuć’, cыstы ‘czysty’, sыrŭoki ‘nogi’, sыtkŭo ‘wszystko’, zuč ‘żuć’, zыč ‘żyć’, zыvы ‘żywy’, zolondek ‘żołądek’.

przyp18 / komentarz/comment /

przyp18 / komentarz/comment / http://www.goralske-narecie.estranky.sk/clanky/oravska-lesna.html [dostęp: 18.05.2013]

] (hist. Herdućka, słow. Oravská Lesná) czy Mutnego [19

] (hist. Herdućka, słow. Oravská Lesná) czy Mutnego [19 przyp19 / komentarz/comment /

przyp19 / komentarz/comment / http://www.goralske-narecie.estranky.sk/clanky/mutne.html [dostęp: 18.05.2013]

] (słow. Mútne).

] (słow. Mútne).Za przykład zróżnicowania leksykalnego pomiędzy dialektami słowackiego może posłużyć słowo ziemniak. W słowackim języku literackim jest ono zbliżone do polskiego i brzmi zemiak. Na Dolnej Orawie, aż do okolic miejscowości Považská Bystrica, nazwą zwyczajową jest švábka, podczas gdy na Górnej Orawie mówi się na to warzywo repa (które, zbliżone do polskiego rzepa, oznacza w odmianie standardowej buraka, na którego Orawcy mówią burgyňa lub bumburdia). Poza interregionalnymi potocznymi nazwami (zemky czy zemáky) można znaleźć jeszcze co najmniej kilka tego typu przykładów [20

przyp20 / komentarz/comment /

przyp20 / komentarz/comment / http://spectator.sme.sk/articles/view/15671/9/ [dostęp: 18.05.2013]

].

].Oprócz tego warto odnotować liczebniki będące skrótowymi lub obocznymi formami względem liczebników z odmiany standardowej; gwary spiskie i orawskie cechują się także m.in. odrębnym systemem stosowania liczebników zbiorowych; ponadto często, zgodnie z zasadą archaizmu peryferycznego [21

przyp21 / komentarz/comment /

przyp21 / komentarz/comment / Archaizm peryferyjny to zjawisko fonetyczne, fonologiczne, wyraz lub forma wyrazowa, zanikłe już w języku ogólnonarodowym, a zachowane w ludowych dialektach (gwarach) położonych na peryferiach danego obszaru językowego.

], zachowują archaiczne formy liczebników podstawowych, np.: siedm, ośm, piyńci, seści, siedmi, a nawet trze, śtyrze (Sikora 2006: 51ff

], zachowują archaiczne formy liczebników podstawowych, np.: siedm, ośm, piyńci, seści, siedmi, a nawet trze, śtyrze (Sikora 2006: 51ff Sikora 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sikora 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Sikora, Kazimierz 2006. „Liczebniki w gwarach Podtatrza (Podhale, Spisz, Orawa)”, LingVaria 2: 49–64. URL: http://www2.polonistyka.uj.edu.pl/LingVaria/archiwa/LV_2_2006_pdf/04_Sikora.pdf [dostęp: 06.10.2012 r.]

). Archaizm ten polega przede wszystkim na braku tzw. epentetycznego (inaczej: znikającego) [e] (por. siedm : siedem, ale: siedmiu) oraz nieskróconej końcówce wyrazowej (por. seści : sześć; siedmi : siedem).

). Archaizm ten polega przede wszystkim na braku tzw. epentetycznego (inaczej: znikającego) [e] (por. siedm : siedem, ale: siedmiu) oraz nieskróconej końcówce wyrazowej (por. seści : sześć; siedmi : siedem).Kod ISO

brak kodu

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- Sikora 1989b

- Ładygin 1985

- Skawiński 1998

- Skawiński 2009

- Kąś 2002

- Sikora 2008

- Kryk-Kastovsky 1996

- Sikora 1989a

- Gawlasová 2012

- Kantor 1997

- Dudok D. 1993

- Dudok M. 1993

- Maxwell 2006

- Sikora 2006

- Moskal 2004

- Štolc 1968

- Zgama 2003

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Współczesna lokalizacja Orawy

- ilustr02

- ilustr03

- Narodowości na Orawie w 1931 r.

- ilustr05

- ilustr06

- Atlas slovenskeho jazyka