Ukrainian dialects

Relationship and identity

Indo-European languages → Slavic languages → East Slavic languages → Ukrainian language(from: Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

)

)Ukrainian dialects discussed in this project are most closely related to other Ukrainian language varieties. Rusyn, Polissian and the tranistional East Slavic varieties, treated by many researchers as Ukrainian, also show some simmilarity. Less closely related are e.g. Belarusian and Russian. Other members of the Slavic languages group are West Slavic languages: Czech and Slovak; Sorbian, Polish and Kashubian; and South Slavic languages: Bulgarian and Macedonian, Serbian and Croatian with Bosnian and Montenegrin and Slovenian (Lewis 2009

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul (red.) 2009. The Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com/].

).

).Dialects

Michał Łesiów differentiates between three regions among the discussed dialects: Sannian, Dniestrian and Volyn-Chełm region (Łesiw 1997 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

).

).Various divisions into dialects, subdialects and accents have been proposed in Ukrainian dialectology. Detailed review of these classifications can be found in Michał Łesiów’s monograph Украiнські говірки у Польщі.

Identity

Michał Łesiów saw a tendency to overestimate the percentage of Poles in pre-war publications, e.g. by counting the Greek Catholics as people of Polish nationality (Łesiw 1997: Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Украïнські говірки у Польщі. Варшава: Украïнський Архів.

243).

243).On the other hand, Ukrainian dialects were spoken not only by the Rusyn or Ukrainian people, but also by the Polish.

Before the Second World War many Orthodox people thought of themselves as the “locals” or Polish people (Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998: XVIII

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998 / komentarz/comment/r / Czyżewski, Feliks & Stefan Warchoł 1998. Polskie i ukraińskie teksty gwarowe ze wschodniej Lubelszczyzny. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

). Many Greek Catholics and Orthodox people chose the Ukrainian nationality because of the local administration which the German staffed with the Ukrainians during the Second World War.

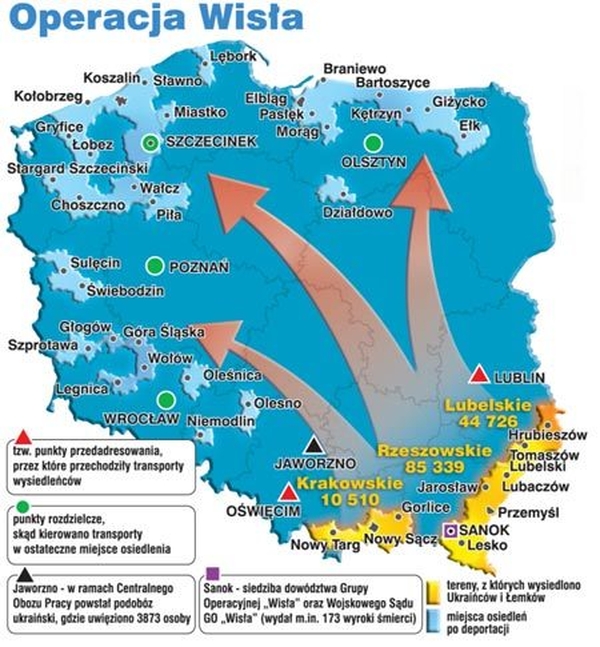

). Many Greek Catholics and Orthodox people chose the Ukrainian nationality because of the local administration which the German staffed with the Ukrainians during the Second World War.In the years 1944-1947, the community officially recognised as Ukrainian was resettled – initially to Soviet Ukraine and later to western and northern Poland due to Operation Vistula. In the 1940’s previously Ukrainian regions were populated with the Polish community.

According to Anna Zielińska (2012: 13

Zielińska 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zielińska 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Zielińska, Anna et al. 2012. „Wielojęzyczność w województwie lubuskim. Stan współczesny”, w: Beata A. Orłowska i Krzysztof Wasilewski (red.) Mniejszości regionu pogranicza polsko-niemieckiego. Gorzów Wielkopolski: Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa, s. 13-23.

), “the East Slavic dialect, different from the standard Ukrainian language” was spoken also by the people with Polish identity in Lubuskie Voivodeship.

), “the East Slavic dialect, different from the standard Ukrainian language” was spoken also by the people with Polish identity in Lubuskie Voivodeship.

Operation Vistula (from: http://www.irekw.internetdsl.pl/akcja_wisla1.jpg).

Timothy Snyder noted that people living on the borderland, who identified themselves as both Poles and Ukrainians, spoke Polish as well as Ukrainian. Furthermore, their cultures were very similar to each other. When writing about ethnic cleansing, he remarked that “in 1947 everyone thought of nationality as of a total phenomenon, meaning that one identity excluded the other, that an individual could be assigned only one national identity” (Snyder 2006: 233-235

Snyder 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Snyder 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Snyder, Timothy 2006. Rekonstrukcja narodów. Polska, Ukraina, Litwa i Białoruś 1569-1999. Sejny: Pogranicze.

).

).

ISO Code

ISO 639-1 uk

ISO 639-2 ukr

ISO 639-3 ukr

SIL UKR

The Linguascale (language classification established by L’Observatoire Linguistique) covers all Ukrainian varieties with: 53-AAA-ed

ISO 639-2 ukr

ISO 639-3 ukr

SIL UKR

The Linguascale (language classification established by L’Observatoire Linguistique) covers all Ukrainian varieties with: 53-AAA-ed

- przyp01

- Karaś 1975

- Tekst ustawy w literackim języku ukraińskim

- Magocsi 2010

- Fałowski 2011

- Łesiw 1997

- Jähnig 2008

- Słabig 2009

- Jarczak 1972

- Zielińska 2012

- Karwowska 2011

- Matelski 1999

- Kuraszkiewicz 1963

- Lisna 2001

- Karaszczuk 2001

- Czyżewski i Warchoł 1998

- Arlt 1940

- Lewis 2009

- Snyder 2006

- Czyżewski 1993

- Czubinski 1877

- Matelski 2012

- Łesiów 1997

- Warchoł 1992

- List of declarations 2012

- Słabig 2012

- Syrnyk i Wicherkiewicz 2006

- Kossakowska 2007

- Bobryk 2011

- Własowski 1961

- Misijuk 2012

- Prystasz 2011

- Czyżewski i Sajewicz 1997

- Czyżewski 1986

- Bandriwski et al. 1988

- MRS 2012

- Syrnyk [rok?]

- Wicherkiewicz 2000

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Mapa mniejszości ukraińskiej IIRP

- Mniejszość ukraińska na Pomorzu Zachodnim

- Mniejszości narodowe w Polsce w latach 1990-1998

- Ukraińskie odmiany na obszarze nadgranicznym

- Grupy narodowościowe w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie

- Akcja „Wisła”

- Podręcznik, materiały do grupowego samokształcenia

- Ogłoszenia w języku ukraińskim w Lubaczowie

- Dwujęzyczna tablica katedry w Przemyślu

- Herb „Płastu”

- Banner promujący Ukraiński Jarmark Młodzieżowy

- Dialekty ukraińskie