Wymysorys / Wilamowicean

Kinship and identity

Language classification

In the Ethnologue language catalogue the Wymysorys language was framed into the following language classification (one that most of the inhabitants of Wilamowice do not agree with) (http://www.ethnologue.com/language/wym):- Indo-European

- Germanic

- West Germanic

- German

- High German

- Middle German

- East Middle German

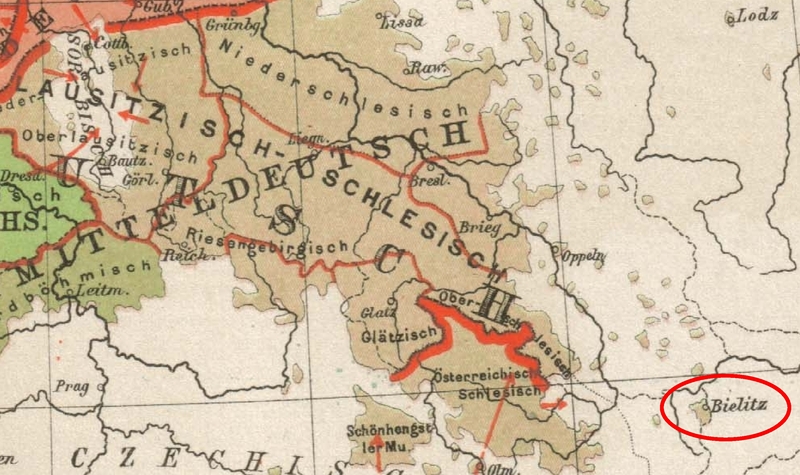

The Bielsko-Biała language enclave in the context of other Silesian dialects.

The Bielsko-Biała language enclave in the context of other Silesian dialects.Own elaboration based on Brockaus' Map of German Dialects,

see: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brockhaus_1894_Deutsche_Mundarten.jpg

Linguistic similarity

Of course, there is no objective criteria that would allow for a definite assessment of whether a given language variety is a language or (still) a dialect. The fact that a given variety has been classified in a particular way is dependent not only on linguistic consideration per se but, also, on tradition, on the way how its users identify themselves and, sometimes, even on political interest. It is, thus, custom to speak of a German language rather than of German languages as Meier & Meier did in their classification (1979: 83-83 Meier & Meier 1979 / komentarz/comment /

Meier & Meier 1979 / komentarz/comment / Meier, Georg F. & Barbara Meier 1979. Sprache, Sprachentstehung, Sprachen. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

), listing „within the North-Germanic group: GDR German, FRG German, Austrian German, Swiss German, Soviet German, Romanian German, North American German, German of France and Luxemburg, German urban varieties, Yiddish".

), listing „within the North-Germanic group: GDR German, FRG German, Austrian German, Swiss German, Soviet German, Romanian German, North American German, German of France and Luxemburg, German urban varieties, Yiddish".Similarity to the German language

It should be, thus, noted that one should not limit oneself solely to the standard German language when writing about the similarity to the German language. It is necessary to compare the given language variety to other varieties, dialects or even German languages to guarantee the comprehensiveness of the description.The list of names which have been used to describe the dialects of Bielsko proves that linguists and historians alike associated them with the Silesian German dialects. However, it should be remembered that the emergence of these dialects is to be ascribed to the descendants of settlers in the Middle Ages who, mainly, came from different regions of today's Germany. It is even likely that once they had lived in what is now known as the Netherlands, Belgium and France. Silesian, thus, is an admixture of dialects which consists of elements from various German language varieties. Initially it probably had been be much more diversified than it was in the 20th century. Throughout the centuries of co-existence of various groups the varieties they employed became much more similar to each other. The scholars of language and history did not attempt to reach into the depths of history and did not try to determine what particular German dialects influenced the Bielitzer MundartenRichard Ernst Wagner referred to the research known to him at the time and wrote about the obvious influence of Thuringia and Upper Saxons dialects on the Silesian varieties of German (Wagner 1935: 193

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

).

).The situation of Wymysorys of Wilamowice was completely different. Virtually every linguist, even amateur ones, who were interested in the town of Wilamowice has attempted to determine the exact origins of the Wymysorys language. According to the previously discussed theory of Latosiński, Wymysorys is connected to the dialects of the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe. The majority of scholars, however, believe that Wymysiöerys is related to the dialects of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave (cf. Kleczkowski 1920

Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1920. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Fonetyka i fleksja. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

,1921

,1921 Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1921. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Składnia (szyk wyrazów). Poznań.

, Mojmir 1930-1936

, Mojmir 1930-1936 Mojmir 1930-1936 / komentarz/comment /

Mojmir 1930-1936 / komentarz/comment / Mojmir, Hermann 1930-1936. Wörterbuch der deutschen Mundart von Wilamowice. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

). Antoni Kleczkowski noted that Thuringians and Eastern Franks played a considerable role in colonisation process which eventually created the language enclave. One modern scholar, Maria Katarzyna Lasatowicz (1992), on the other hand, believes that it were the settlers from Thuringia, Meissen, Upper Saxony, Bavaria, Austria and Hesse that indirectly led to the development of the local dialects. The origin of the Wymysorys language became a dissertation topic in the University of Sydney. Carlo Ritchie analysed the Wymysorys phonology and morphology and concluded that the similarities indicate a relation to Middle German dialects. He has also taken notice of its Low German influences (2012: 86-87

). Antoni Kleczkowski noted that Thuringians and Eastern Franks played a considerable role in colonisation process which eventually created the language enclave. One modern scholar, Maria Katarzyna Lasatowicz (1992), on the other hand, believes that it were the settlers from Thuringia, Meissen, Upper Saxony, Bavaria, Austria and Hesse that indirectly led to the development of the local dialects. The origin of the Wymysorys language became a dissertation topic in the University of Sydney. Carlo Ritchie analysed the Wymysorys phonology and morphology and concluded that the similarities indicate a relation to Middle German dialects. He has also taken notice of its Low German influences (2012: 86-87 Ritchie 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Ritchie 2012 / komentarz/comment / Ritchie, Carlo 2012. Some Considerations on the Origins of Wymysorys. Sydney: The University of Sydney (praca licencjacka).

).

).The similarities to other German language enclaves existing up until the end of the II World War in Silesia should be noted as well. Adam Kleczkowski pointed out the resemblance to the Schewaud dialect (1920: 7

Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1920. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Fonetyka i fleksja. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

). Szynwałd (Schönwald, presently Bojków), constitutes the southern district of Gliwice. This lead was also taken up by the historian Antoni Barciak who even attempted to search for any evidence of contact between these two localities in Middle Age documents (2001: 90-91

). Szynwałd (Schönwald, presently Bojków), constitutes the southern district of Gliwice. This lead was also taken up by the historian Antoni Barciak who even attempted to search for any evidence of contact between these two localities in Middle Age documents (2001: 90-91 Barciak 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Barciak 2001 / komentarz/comment / Barciak, Antorni (red.) 2001. Wilamowice. Przyroda, historia, język, kultura, oraz społeczeństwo miasta i gminy. Wilamowice: Urząd Gminy.

).

). Furthermore, Karl Olma recognizes the similarity between Wymysorys and the Anhalt-Gatsh (Hołdunów and Gać) dialect-enclave located near Lędziny. These localities were founded by the inhabitants of the nearby village Kozy(Seibersdorf) who are Calvinists. In 1775, accompanied by armed Prussian military forces, they left their homeland and established new settlements in the part of Silesia which was, then, ruled by Prussia (Olma 1983: 28-33

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

).

). Wymysorys and the dialects of the Silesian language islands have not yet been subjected to thorough comparative analyses. It is justified to suspect that there might be no living speakers of any language of the Silesian language enclaves, hence this kind of analysis would have to be conducted on written materials. The Anhalt-Gatsh language island was described by Wackwitz (1932) whereas, e.g., Gusinde (1911

Gusinde 1911 / komentarz/comment /

Gusinde 1911 / komentarz/comment / Gusinde, Konrad 1911. Eine vergessene Sprachinsel im polnischen Oberschlesien (die Mundart von Schönwald bei Gleiwitz). Breslau: Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. [przedruk: 2012]

) did research on the Schönwald dialect. A reprint of Gusinde's work appeared in 2012. Trembacz (1971

) did research on the Schönwald dialect. A reprint of Gusinde's work appeared in 2012. Trembacz (1971 Trambacz 1971 / komentarz/comment /

Trambacz 1971 / komentarz/comment / Trambacz, Waldemar 1971. Die Mundart von Bojków. Versuch einer phonetisch-phonologischen Betrachtungsweise. Poznań : UAM [nieopublikowana rozprawa doktorska].

) took up this topic in his research. Yet another German language enclave (Gościęcin) was described recently by Felicja Księżyk (2008

) took up this topic in his research. Yet another German language enclave (Gościęcin) was described recently by Felicja Księżyk (2008 Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment /

Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment / Księżyk, Felicja 2008. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Kostenthal. Geschichte und Gegenwart. Berlin: trafo.

).

).Similarity to other languages

A very large portion of the residents of Wilamowice do not agree with scholarly opinion regarding the resemblance of Wymysorys to various German dialects. This belief has grown even stronger due to the popularity and spreading of Latosiński's opinions on the language:As one yearns to establish where did the first Wilamowiceans come from it's pivotal to discuss the local dialect, as it is the dialect that will provide the most accurate suggestions (1909: 13These Anglo-Saxon, Frisian or Flemish origins are often anecdotally proved by the local population by providing accounts of journeys to England or the Netherlands. There, native Wilamowiceans despite having no prior knowledge of the respective native languages were able to easily communicate by using only their own Wymysorys (cf. e.g. Libera i Robotycki 2001Latosiński 1909 / komentarz/comment /

Latosiński, Józef 1909. Monografia Miasteczka Wilamowic. Na podstawie źródeł autentycznych. Kraków. [przedruk 1990].).

Libera i Robotycki 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Libera i Robotycki 2001 / komentarz/comment / Libera, Zbigniew i Czesław Robotycki 2001. „Wilamowice i okolice w ludowej wyobraźni”, w: Barciak 2001: 371-400.

, Filip 2005

, Filip 2005 Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment / Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.

).

). Although Józef Latosiński himself was in favour of a German theory of origins of Wymysorys he did, also, notice several other Germanic influences. He compiled a vocabulary list a few pages long which comprised of these words whose etymology can be traced to "the Gothic language" [sic!], "the Old North dialect", "the Old Saxon dialect", "the Anglo-Saxon dialect", "the Old Frisian dialect", Dutch and English (1909: 267 – 270

Latosiński 1909 / komentarz/comment /

Latosiński 1909 / komentarz/comment / Latosiński, Józef 1909. Monografia Miasteczka Wilamowic. Na podstawie źródeł autentycznych. Kraków. [przedruk 1990].

).

).Opinions on Wymysorys (and Hałcnovian) can be expressed by the words of Józef Łepkowski, a professor of archeology at the Jagielloński University. In his letter from Kęty from the 20th of September 1853, published in Gazeta Warszawska he writes the following:

A peculiar thing is this speech! As if it's Yiddish, as if it's English but, obviously, kind of rings German. [...] "The language of those living in Wilamowice and Hałcnów, despite being many centuries in contact with the Slavic of the Polish kind on one hand, and of the Silesian kind on the other, retained much of its harsh gothicness; it is a Germanic dialect, but one snatched from the Middle Ages and frozen in time." Others deem the settlers as Dutchmen who arrived here during the very first religious conflicts. - I bear no knowledge on the differences between the Old German speech and the one of modernity, nor can I speak any Dutch, and so I am unable to classify this dialect - even more so that nobody except the colonists themselves can understand the language. In German or Polish they answer to a stranger, in Polish they pray but they did retain, as if mummified, their own dialect. (translated from the Polish original as quoted in Filip 2005: 150Also Uriel Weinreich, in his article (1958Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.).

Weinreich 1958 / komentarz/comment /

Weinreich 1958 / komentarz/comment / Weinreich, Uriel 1958. Yiddish and Colonial German in Eastern Europe: The Differential Impact of Slavic. Moscow-`s-Gravenhage: Mouton.

), noted the similarities between Wymysorys (and, broadly speaking, German colonial dialects) and Yiddish.

), noted the similarities between Wymysorys (and, broadly speaking, German colonial dialects) and Yiddish.Contacts with Polish

Wymysorys has been much extensively influenced by the Polish language, as discussed in the works of Tomasz Wicherkiewicz and Jadwiga Zieniukowa (2001: 502-517 Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz i Jadwiga Zieniukowa 2001. „Sytuacja etnolektu wilamowskiego jako enklawy językowej”, w: Barciak 2001: 489-519.

). Following the research of Kleczkowski (1920

). Following the research of Kleczkowski (1920 Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1920. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Fonetyka i fleksja. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

, 1921

, 1921 Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1921. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Składnia (szyk wyrazów). Poznań.

) and Lasatowicz (1992

) and Lasatowicz (1992 Lasatowicz 1992 / komentarz/comment /

Lasatowicz 1992 / komentarz/comment / Lasatowicz, Maria Katarzyna 1992. Die deutsche Mundart von Wilamowice zwischen 1920 und 1987.

) they determined that the most frequent types of borrowings from Polish to Wymysorys are: kinship terms, names, surnames, pseudonyms, geographic names; names of plants and animals, household goods, culinary dishes, clothes and months; vocabulary related to the religious sphere and schooling (Wicherkiewicz, Zieniukowa 2001: 503-504

) they determined that the most frequent types of borrowings from Polish to Wymysorys are: kinship terms, names, surnames, pseudonyms, geographic names; names of plants and animals, household goods, culinary dishes, clothes and months; vocabulary related to the religious sphere and schooling (Wicherkiewicz, Zieniukowa 2001: 503-504 Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz i Jadwiga Zieniukowa 2001. „Sytuacja etnolektu wilamowskiego jako enklawy językowej”, w: Barciak 2001: 489-519.

). Similarly as in other Bielsko-Biała dialects, Wymysorys would often amalgamate Germanic word roots with Polish suffixes; or vice versa, combine Polish roots with Germanic suffixes. For example, auspaśjyn (aus + paśjyn) can be translated as „wypaść się” (to batten), obrozła (obroz + ła [a diminutive suffix]) as ‘a picture (diminutive)’.

). Similarly as in other Bielsko-Biała dialects, Wymysorys would often amalgamate Germanic word roots with Polish suffixes; or vice versa, combine Polish roots with Germanic suffixes. For example, auspaśjyn (aus + paśjyn) can be translated as „wypaść się” (to batten), obrozła (obroz + ła [a diminutive suffix]) as ‘a picture (diminutive)’.The poetry of Florian Biesik can provide evidence of how Polish influenced the syntax of Wymysorys. One can find examples of double negation which virtually does not occur in contemporary standard German languages (Wicherkiewicz 2003: 104, 413

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

; Wicherkiewicz, Zieniukowa 2001: 513

; Wicherkiewicz, Zieniukowa 2001: 513 Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz i Jadwiga Zieniukowa 2001. „Sytuacja etnolektu wilamowskiego jako enklawy językowej”, w: Barciak 2001: 489-519.

): fóm cąła wyjł nimyt ny hjén – „o płaceniu nikt nie chce słyszeć” (nobody wants to hear anything [nothing] about paying). Also, Wymysorys does not adhere strictly to the sequence of tenses principle which can be interpreted as another example of polish influence (Wicherkiewicz 2001: 514

): fóm cąła wyjł nimyt ny hjén – „o płaceniu nikt nie chce słyszeć” (nobody wants to hear anything [nothing] about paying). Also, Wymysorys does not adhere strictly to the sequence of tenses principle which can be interpreted as another example of polish influence (Wicherkiewicz 2001: 514 Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2001. „Piśmiennictwo w etnolekcie wilamowskim”, w: Barciak 2001: 520-538.

; Kleczkowski 1921: 3

; Kleczkowski 1921: 3 Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1921. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Składnia (szyk wyrazów). Poznań.

).

).These numerous borrowings from the Polish language became a reason for jokes told by the inhabitants of nearby towns and villages, regardless of whether they were Polish or German speaking. Supposedly this is the type of songs that Wilamowiceans used to sing (Wicherkiewicz, Zieniukowa 2001: 515

Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz i Jadwiga Zieniukowa 2001. „Sytuacja etnolektu wilamowskiego jako enklawy językowej”, w: Barciak 2001: 489-519.

):

): | An dyr wiyrzba zyct yn zajonc myta fysła pomerdajonc żebym tak jo fisła miała to bym se tyż pomerdała | A rabbit's sitting on a willow waggling its small feet if I had such small feet I'd waggle them as well. |

Language, dialect, a group of dialects?

The status according to its speakers

The commentary regarding the first paragraph of this subchapter can be related to the past inhabitants of Wilamowice as well; the language vs dialect dichotomy was unknown to them. Hermann Mojmir, Wilamowicean scholars native to the town, considered it a dialect of German (Mojmir 1930-1936 Mojmir 1930-1936 / komentarz/comment /

Mojmir 1930-1936 / komentarz/comment / Mojmir, Hermann 1930-1936. Wörterbuch der deutschen Mundart von Wilamowice. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

). His own brother, Florian Biesik used his narrative poems and poetry to describe it as a language (e.g. Wicherkiewicz 2003: 507

). His own brother, Florian Biesik used his narrative poems and poetry to describe it as a language (e.g. Wicherkiewicz 2003: 507 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

). As Rinaldo Neels' sociolinguistic research (2012

). As Rinaldo Neels' sociolinguistic research (2012 Neels 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Neels 2012 / komentarz/comment / Neels, Rinaldo 2012. De nakende taaldood van het Wymysojer, een Germaans taaleiland in Zuid-Polen. Een socuilinguïstische analyse. Leuven: Katolieke Universiteit Leuven [nieopublikowana praca doktorska].

) has shown, contemporary speakers of Wymysiöeryś are more likely to agree with Biesik. Similarly, the regional poet Józef Gara (2004

) has shown, contemporary speakers of Wymysiöeryś are more likely to agree with Biesik. Similarly, the regional poet Józef Gara (2004 Gara 2004 / komentarz/comment /

Gara 2004 / komentarz/comment / Gara, Józef 2004. Zbiór wierszy o wilamowskich obrzędach i obyczajach oraz słownik języka wilamowickiego. Wilamowice: Stowarzyszenie na Rzecz Zachowania Dziedzictwa Kulturowego Miasta Wilamowice „Wilamowianie”.

) sees it as a language.

) sees it as a language.Status according to disinterested scholars

As it has been mentioned, virtually all of the scholars researching Bielsko-Biała dialects were native, local intellectuals. The case of Wymysorys looks different; it has become an object of interest for scholars world-wide.The aforementioned "Bielsko-Biała" scholars deemed Wymysiöerys a dialect of German. A headmaster of a secondary school in Wadowice, Ludwik Młynek, wrote that Wymysiöeryś can be considered as dialect.

Nonetheless, within the last twenty years the attitudes of scholars towards Wymysorys have undergone evolution. In the 1990s it was still described as a dialect (Morciniec 1995

Morciniec 1995 / komentarz/comment /

Morciniec 1995 / komentarz/comment / Morciniec, Norbert 1995. „Zur Stellung des deutschen Dialekts von Wilmesau/Wilamowice in Südpolen“. w: G. Keil & J.J. Menzel (red.) Anfänge und Entwicklung der deutschen Sprache im mittelalterischen Schlesien, (Schlesische Forschungen 6). Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag. 71-81.

, Lasatowicz 1992

, Lasatowicz 1992 Lasatowicz 1992 / komentarz/comment /

Lasatowicz 1992 / komentarz/comment / Lasatowicz, Maria Katarzyna 1992. Die deutsche Mundart von Wilamowice zwischen 1920 und 1987.

) although in 1990 Alfred F. Majewicz called it a language. At the turn of the new millennium, researchers began to use the term "ethnolect" (Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001

) although in 1990 Alfred F. Majewicz called it a language. At the turn of the new millennium, researchers began to use the term "ethnolect" (Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz i Jadwiga Zieniukowa 2001. „Sytuacja etnolektu wilamowskiego jako enklawy językowej”, w: Barciak 2001: 489-519.

; Wicherkiewicz 2001

; Wicherkiewicz 2001 Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2001. „Piśmiennictwo w etnolekcie wilamowskim”, w: Barciak 2001: 520-538.

; Wicherkiewicz 2003

; Wicherkiewicz 2003 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

). In more recent works, however, scholars are in agreement in employing the term "language" (Andrason 2010

). In more recent works, however, scholars are in agreement in employing the term "language" (Andrason 2010 Andrason 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Andrason 2010 / komentarz/comment / Andrason, Alexander 2010. “Expressions of futurity in the Vilamovicean language”, Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 40: 1-10.

; Andrason 2011

; Andrason 2011 Andrason 2011 / komentarz/comment /

Andrason 2011 / komentarz/comment / Andrason, Alexander 2011. “Vilamovicean verbal system – Do the Preterite and the Perfect mean the same?”, Linguistica Copernica I(5): 271-285.

; Neels 2012

; Neels 2012 Neels 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Neels 2012 / komentarz/comment / Neels, Rinaldo 2012. De nakende taaldood van het Wymysojer, een Germaans taaleiland in Zuid-Polen. Een socuilinguïstische analyse. Leuven: Katolieke Universiteit Leuven [nieopublikowana praca doktorska].

; Ritchie 2012

; Ritchie 2012 Ritchie 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Ritchie 2012 / komentarz/comment / Ritchie, Carlo 2012. Some Considerations on the Origins of Wymysorys. Sydney: The University of Sydney (praca licencjacka).

). Despite this fact, however, some academics and lecturers of Polish universities tend to disapprove of describing Wymysiöeryś as a language.

). Despite this fact, however, some academics and lecturers of Polish universities tend to disapprove of describing Wymysiöeryś as a language.Status according to different organizations - codes on the dialects/languages.

The ISO-639-3 code for Wymysiöeryś/Wymysorys is wym. Also, many webpages state that the Library of Congress granted the same code to Wymysorys on the 18th of June 2007. The Library's website does not support this information as there is mention of Wymysorys on the Library's 2007 list (http://www.loc.gov/marc/languages/language_name.html) nor any later list (http://www.loc.gov/marc/languages/languagechg.html). Wymysiöeryś does not have its code in the linguascaleIdentity

National and ethnic

The ethnic and national identity of the German-speaking inhabitants of Bielsko, Biała and their adjacent settlements in the First Polish Republic period cannot be determined from any known sources - it may be that there are none. It can be assumed that they were aware of the existing differences between them and their Polish-speaking neighbours; at that time, however, identity was formulated mostly by a combination of religious, class and country elements.As Kleczkowski (1915: 390

Kleczkowski 1915 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1915 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1915. „Dyalekty niemieckie na ziemiach polskich”, w: H. Ułaszyn, i in. Język polski i jego historya z uwzględnieniem innych języków na ziemiach polskich. cz. II. Kraków: Nakładem Akademii Umiejętności. Ss. 387-394.

) wrote: "The powerful 14th and 15th century German colonisation of the Lesser Poland region weakens with time, and in the second half of the 18th century, still in the period of Polish reign, it starts anew, initially in Silesia". Belonging to a given country-state was still a very strong factor in determining one's identity, even in the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, territories on both sides of the river Biała were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Nonetheless, ideals of nationalism began to spread first in the towns, and later within rural areas. The clash between this new type of identity based on one's "nationality" and the old one based on close ties with one's small homeland and the country-state is depicted in the reminiscent article by Eugeniusz Bilczewski, a teacher from Wilamowice:

) wrote: "The powerful 14th and 15th century German colonisation of the Lesser Poland region weakens with time, and in the second half of the 18th century, still in the period of Polish reign, it starts anew, initially in Silesia". Belonging to a given country-state was still a very strong factor in determining one's identity, even in the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, territories on both sides of the river Biała were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Nonetheless, ideals of nationalism began to spread first in the towns, and later within rural areas. The clash between this new type of identity based on one's "nationality" and the old one based on close ties with one's small homeland and the country-state is depicted in the reminiscent article by Eugeniusz Bilczewski, a teacher from Wilamowice:Peaceful and placid as they were, and seeing themselves primarily as "Wilamowiceans", they were now faced with the demand to formulate their identity at a national level. They used to say "wir sein esterreichyn", we are Austrians as we live in Austria. Every subjects in this monarchy was considered an Austrian regardless of the language they spoke. Austria and Franz Joseph I were symbols of power and strength, Vienna - welfare and a dream of every single citizen (as quoted in Filip 2005: 162Other towns and villages of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave could have experienced a similar situation.Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.).

The situation in Wilamowice was slightly different. The sense of being different was wide-spread and very strong. Some of the residents of Wilamowice felt they are members of the Polish nation, particularly the archbishop Józef Bilczewski and poet Florian Biesik. On the other hand, organizations of a strictly German nature, such as the educational association Schulverein, were active in Wilamowice.

The research by Rinaldo Neels has shown that contemporary speakers of Wymysrys share a double identity. On the national level they are Polish, on the regional level - Wilamowicean. (2012: 128-131

Neels 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Neels 2012 / komentarz/comment / Neels, Rinaldo 2012. De nakende taaldood van het Wymysojer, een Germaans taaleiland in Zuid-Polen. Een socuilinguïstische analyse. Leuven: Katolieke Universiteit Leuven [nieopublikowana praca doktorska].

).

).Religious identity

Catholicism was the dominant religion among the colonists settling in the vicinity of Bielsko. However, in the 15th century the Duchies of Oświęcim and Cieszyn found themselves under Czech influence which led to the fact that a portion of the inhabitants of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave accepted the Hessite religion as their own. By 1424, Hussitism became the dominant religion of Wilamowice, Kozy and Lipnik (Wurbs 1981: 16 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Not for long, however, as the area would turn back to Catholicism, a state which would last until the reformation period.

). Not for long, however, as the area would turn back to Catholicism, a state which would last until the reformation period.In Wilamowice and Hałcnów Catholicism was the preferred denomination. In Biała itself most of the population was Catholic as well. Nonetheless, there were Evangelic among the German-speaking population of the town.

It is also worth to mention that in the 17th century Calvinism had its share of followers east of the Biała river, in Kozy and Wilamowice as well (Urban 2001: 110-111

Urban 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Urban 2001 / komentarz/comment / Urban, Wacław 2001. „W granicach królestwa Polskiego 1457-1772”. w: Barciak 2001: 98-115.

).

). ISO Code

ISO 639-3 wym

- Rozalia Hanusz - opowieść o Wilamowicach

- biogram Heleny Biba - część 1

- biogram Heleny Biba - część 2

- AKowalczyk i TKról

- H. Biba w ogrodzie 1

- H. Biba w ogrodzie 2

- J. Gara - powitanie

- J. Gara o okolicy w Wilamowicach

- J. Gara i jego twórczość (A)

- J. Gara i jego twórczość (B)

- J. Gara o swoim życiu

- J. Gara o innych gwarach

- J. Gara o Żydach wilamowskich

- Pierzowiec 1

- Pierzowiec 2

- A.Foks i H. Biba - strój wilamowski 2

- J. Gara o Hałcnowie

- Florian Biesik - poemat "Óf jer wełt"

- A.Foks i H. Biba - strój wilamowski 1

- artykuł o języku wilamowskim "Rzeczpospolita" cz.1

- próba zespołu Wilamowice - Diöt fum hejwuł...

- próba zespołu Wilamowice

- FotoRzepa - film o Wilamowicach

- Wilamowice w Sejmie część 2

- film flamandzkiej TV o Wilamowicach z 1977 r.

- E. Matysiak śpiewa "Pater s'foter..."

- Wilamowice w Sejmie część 1

- Wilamowice w Sejmie część 3

- H.Rozner opowiada o rodzinie na fotografii

- H. Nowak śpiewa "Wymysiöejer śejny måkja"

- Kontakty językowe wilamowsko-polskie

- Wurbs 1981

- Filip 2005

- Wicherkiewicz 2001

- Wicherkiewicz 2003

- Bock 1916a

- Barciak 2001

- Wagner 1935

- Libera i Robotycki 2001

- Bukowski 1860

- Latosiński 1909

- Kleczkowski 1920

- Kleczkowski 1921

- Mojmir 1930-1936

- Lasatowicz 1992

- Ritchie 2012

- Wackwitz 1932

- Trambacz 1971

- Księżyk 2008

- Weinreich 1958

- Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001

- Neels 2012

- Gara 2004

- Morciniec 1995

- Andrason 2010

- Andrason 2011

- Kleczkowski 1915

- Młynek 1907

- Król 2011

- Augustin 1842

- Anders 1933

- Ryckeboer 1984

- Morciniec 1984

- Besch et al 1983

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- Jungandreas 1933

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- opowieść o dawnych Wilamowicach

- autor T.Król czyta fragmenty "s'Ława fum Wilhelm"

- Anna Kowalczyk czyta fragment s'Ława fum Wilhelm

- Józef Gara - fragment "Óf jer wełt" F. Biesika

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Dy Wajnaochta"

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Ym Wynter"

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Z Śwojmła kom cyryk"

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Paoter s'Faoter"

- J.Gara śpiewa swój utwór "Śłöf maj Kyndła"

- J.Gara śpiewa swój utwór "Śtyły Naocht"

- J.Gara śpiewa swój utwór "Jyr kyndyn kumt oły"

- polskojęzyczny wstęp w rękopisie Floriana Biesika

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- strona tytułowa manuskryptu F. Biesika

- Mapa Wilamowic (duży rozmiar)

- Mapa Wilamowic (mały rozmiar)

- fotografia z wesela w Wilamowicach

- fotografia śmierguśników w Wilamowicach

- Pamiętniki Jana Danka 'Płaćnika' z 1923 r.

- fragment Pamiętników Jana Danka po wilamowsku

- fotografia weselnych śmierguśników w Wilamowicach

- poemat T. Króla - "s'Ława fum Wilhelm"

- siedziba Stowarzyszenia "Wilamowianie"

- Stowarzyszenie "Wilamowianie"

- reklama po wilamowsku 1

- reklama po wilamowsku 2

- spotkanie Stowarzyszenia

- manuskrypt z przydomkami domostw w Wilamowicach

- strona tytułowa rękopisu J.Rosnera z przydomkami

- strona tytułowa rękopisu Pamiętników J.Danka

- rękopis wierszyka "Ys wa amół ym wynter kałt"

- maszynopis piosenki "Fo ynsyn raichia faldyn"

- rękopis kołysanki "Kyndła maj, śłöf śun aj!"

- L. Młynek "Narzecze wilamowickie"- strona tytułowa

- program konferencji nt.języków zagrożonych, Sejm

- konferencja międzynarodowa w Wilamowicach, 2014 r.

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 1

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 2

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 3

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 4

- Wilamowice w Sejmie i kard. K.Nycz

- kard. K. Nycz w Sejmie

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 5

- fotografia 3 dziewcząt i mężczyzny z Wilamowic

- fotografia wesela w Wilamowicach 1

- fotografia wesela w Wilamowicach 2

- kartka pocztowa po wilamowsku

- tablice "Kolorowa żałoba w Wilamowicach" T.Króla

- A.Kleczkowski Dialekt Wilamowic-fonetyka i fleksja

- A.Kleczkowski Dialekt Wilamowic-składnia

- H.Mojmir-"Woerterbuch der Mundart von Wilamowice"

- H.Anders - "Gedichte von Florian Biesik"

- T. Wicherkiewicz - "The Making of a Language"

- nagrobek K. i J.Foksów - Wilamowice

- nagrobek T. i J.Foksów - Wilamowice

- nagrobej F. i K. Zejmów

- nagrobek F. i A. Moslerów - Wilamowice

- grób A. Rosner Korczyk - Wilamowice

- fragment nt.Wilamowic w rękopisie F.Augustina

- strona tytułowa Bukowski 1860

- fotografia stroju żałobnego w Wilamowicach 1

- fotografia stroju żałobnego w Wilamowicach 2

- Samogłoski języka wilamowskiego

- Wymysorys monophtong vowels