Tatar

General information

This chapter is focused on the extinct language varieties used by the Tatars of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (which died out in the 16th/17th century).Terminology

The term ‘Tatar language’ has several references. At present, it generally refers to the ethnic language of Tatars, used as one of the official languages in the Republic of Tatarstan. The users of this language also live in other regions of the Russian Federation, as well as in the former Soviet Republics or Turkey. There are three dialects of Tatar: Middle (Kazan), Western (Saratov, Bashkortostan) and Eastern (Western Siberia). Tatar is spoken by 6,496,000. TAT is the International language code SIL for the Tatar language (Lewis 2009: 571 Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, Paul M. (ed.) 2009. Ethnologue: languages of the world. 16th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

).

).The study presented below focuses on the Tatar language understood as a set of dialects used by the ancestors of the Tatars, historically living in the area of present-day Belarus, Poland and Lithuanian.

Contemporaries Polish, Lithuanian and Belarus Tatars are the descendants of the Kipchaks settlers, who, from the 14th c. were coming to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Golden Horde’s territory.

The precise definition of Tatar, as the language of the Tatar settlers on the Polish territory, is almost impossible as there was no one common language of the ancestors of contemporary Tatars in any moment in history.

The first Tatar settlers in Rus and Lithuania spoke several dozens of Bashkirian and Kipchak dialects (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 202

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). They were not different dialects of the same language, however, the level of mutual intelligibility is difficult to establish. What is more, the Tatars share their language traditions with e.g. the Karaims, whose language is still alive. As Tyszkiewicz (1989

). They were not different dialects of the same language, however, the level of mutual intelligibility is difficult to establish. What is more, the Tatars share their language traditions with e.g. the Karaims, whose language is still alive. As Tyszkiewicz (1989 Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

) writes,”... (At) the beginning of the 15th century, ‘Tatar’ that is the Kipchak, was spoken by the Ulus from Volga area, as well as the Armenians and the Karaims” (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 159-160

) writes,”... (At) the beginning of the 15th century, ‘Tatar’ that is the Kipchak, was spoken by the Ulus from Volga area, as well as the Armenians and the Karaims” (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 159-160 Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). Certainly, we could replace the term ‘the Tatar language’ with ‘the Tatar dialects’.

). Certainly, we could replace the term ‘the Tatar language’ with ‘the Tatar dialects’.The Tatar dialects, however, comprises also the dialects which are in a continuum with the Karaim language - the language which now serves an identification role for the Karaim community. Thus, the issue of the terminological ambiguity would remain unsolved. The advantage of the term ‘the Tatar language’ is the sociolinguistic context which is associated with this term by the Polish Tatars (see: Current status of Tatar). In relation to the positive connotations of the term ‘Tatar language’, shared by the members of the Tatar community in Poland, the use of the term ‘Tatar dialects” would not be justified. It does not change the fact that the term ‘Tatar language’ needs to be treated as a working term, a compromise, which allows to refer to the linguistic heritage of the Tatar settlers on the Polish territory. At the same time, this term comprises the present day Tatar cultural-linguistic context. Despite the above-mentioned distinction between Tatar died out in the 16th c. and Tatar used now, it is still difficult to avoid ambiguity of ‘the Tatar language’ meaning in the context of the current sociolinguistic conditions concerning this language in Poland. The number of the Polish Tatars interested in the language is increasing. A good example of that is the Tatar language course organised since 2012 in one of the primary schools in Bialystok. The advertisement promoting the language course on the website www.tataria.eu, encourages readers to learn a phrase: “After 400 years of ‘silence’, we have the chance to speak the language of our ancestors!” Interviews with a representative of the Tatar community, however, indicate that the Tatars are aware that there was no such thing as the language of their ancestors. The learning of Tatar is based on the present-day materials used for Tatar learning in the Republic of Tatarstan, translated from Russian. The reasons for that were mentioned before and are further described in the section Outline of sociolinguistic situation.

One should also mention the existence of Crimean Tatar, which is not synonymous with Tatar. Crimean Tatar, just like Tatar - both the one with the code TAT and a set of dialects used in the past on the territory of the Great Duchy of Lithuania - derives from a Kipchak language (Jankowski 1997: 67

Jankowski 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jankowski 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Jankowski, Henryk 1997. "Nazwy osobowe Tatarów litewsko-polskich", Rocznik Tatarów Polskich. Tom IV. Gdańsk: Związek Tatarów Polskich, s. 59-90.

). The Kipchak language is an already extinct language from the Kipchak group. It was one of the languages commonly used on the territory of the Golden Horde. Studies on the Kipchak language often mention Kipchak dialects (cf. Berta 2006: 158

). The Kipchak language is an already extinct language from the Kipchak group. It was one of the languages commonly used on the territory of the Golden Horde. Studies on the Kipchak language often mention Kipchak dialects (cf. Berta 2006: 158 Berta 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Berta 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Berta, Árpád 2006. "Middle Kipchak", w: Lars Johnson & Éva Á. Csató (eds.) The Turkic Languages. London – New York: Routledge, s. 158-165.

) - if, to a certain extent, we understand a language as an unified system, this term better reflects the situation of the Kipchak language in the 13th-16th century. Worth emphasising is the difference between the terms ‘the Kipchak language’ and ‘the Kipchak languages’, which comprises the group of Turkic languages also used at present - e.g. Karaim, Kazakh or Crimean Tatar. The Crimean Tatar language is spoken by 483,990 people (Lewis 2009: 578

) - if, to a certain extent, we understand a language as an unified system, this term better reflects the situation of the Kipchak language in the 13th-16th century. Worth emphasising is the difference between the terms ‘the Kipchak language’ and ‘the Kipchak languages’, which comprises the group of Turkic languages also used at present - e.g. Karaim, Kazakh or Crimean Tatar. The Crimean Tatar language is spoken by 483,990 people (Lewis 2009: 578 Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, Paul M. (ed.) 2009. Ethnologue: languages of the world. 16th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

), of which c. 260,000 live in Crimea.

), of which c. 260,000 live in Crimea. Crimean Tatar has an international language code CRH.

Also worth mentioning is the fact that in the history of the Tatar settlement on the Polish territory, we can find references to the Crimean Tatars who started to settle on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania after Vytautas died. The earlier Tatar settlers, however, spoke the dialects, which are part of the common linguistic heritage of the present day Kipchak-Cuman group of the Kypchak languages - therefore also the Crimean Tatar language. Indeed, people who came from Crimea spoke the variation, which may have been considered the separate Crimean Tatar language (cf. Łapicz 1986: 35

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Łapicz, Czesław 1986. Kitab Tatarów litewsko-polskich (Paleografia. Grafia. Język). Toruń: UMK.

).

).Linguonims

Names used for the Tatar language: język tatarski (Polish), татар теле (Tatar); Names for the Tatar language tat: The Tatar language (English), jezyk tatarski (Polish), татар теле, татарча – also written in the Latin alphabet as, respectively, tatar tele i tatarça and in the Arabic alphabet as „تاتارچا” (Tatar), tата́рский язы́к (Russian)The users community

The history of the Tatar settlement on the Polish territory

Tatars who live in Poland are the descendants of the Golden Horde’s inhabitants - the medieval country on the Volga River, which probably owes its name to the colour of the cloth covering the khan’s tent (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 110 Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). Since the 14th century, the Tatars started to settle gradually in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, mainly as a result of the political actions of Vytautas. The duke, in regard to war waged with the Teutonic Orders, aimed at the greatest possible stabilisation on the Eastern borderlands of the Duchy and gave asylum both to the claimants to the throne of Orda khan and to the throne of sultan in Turkey. Jan Dlugosz dates back the beginnings of the Tatar settlement on the Polish territory, connected with the purposeful policy of Lithuanian dukes, to 1397. It is still worth emphasising that the individual Tatar settlers, mainly merchants, arrived to the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as early as in the 13th century (Łapicz 1986: 59

). Since the 14th century, the Tatars started to settle gradually in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, mainly as a result of the political actions of Vytautas. The duke, in regard to war waged with the Teutonic Orders, aimed at the greatest possible stabilisation on the Eastern borderlands of the Duchy and gave asylum both to the claimants to the throne of Orda khan and to the throne of sultan in Turkey. Jan Dlugosz dates back the beginnings of the Tatar settlement on the Polish territory, connected with the purposeful policy of Lithuanian dukes, to 1397. It is still worth emphasising that the individual Tatar settlers, mainly merchants, arrived to the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as early as in the 13th century (Łapicz 1986: 59 Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Łapicz, Czesław 1986. Kitab Tatarów litewsko-polskich (Paleografia. Grafia. Język). Toruń: UMK.

).

).The Tatar settlement on the Polish and Lithuanian territory was voluntarily, although among the Tatars who settled on the land of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were also prisoners of war (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 146

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

).

). The settlers before the main wave initiated by Vytautas, sought asylum on the Lithuanian territory also for the religious reasons - Ozbeg, Khan of the Golden Horde in years 1312-1342, wanted to force the entire state to convert to Islam.

Lithuania guaranteed cultural and religious tolerance, which enabled the first Tatar settlers to maintain shamanism.

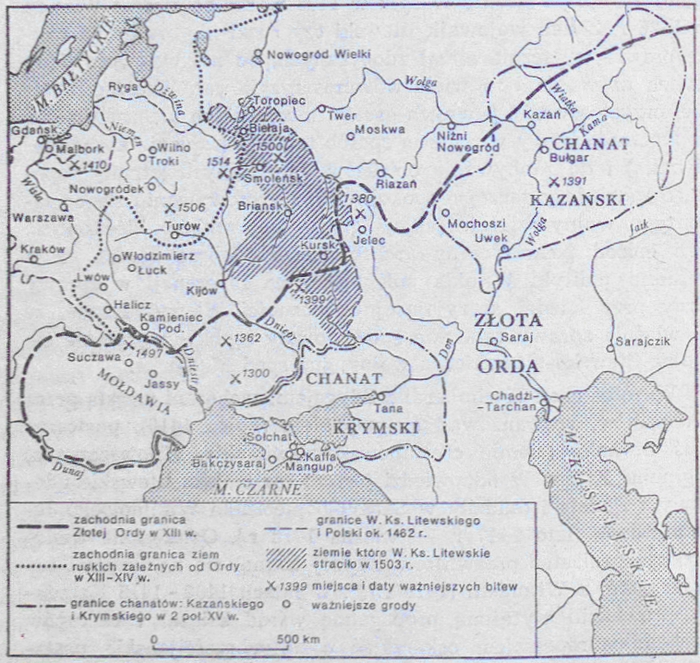

The Tatars and their neighbours in the 13th-15th c. (after: Tyszkiewicz 1989: 128

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

).

).The main Tatar settlement areas were: the surroundings of Trakai, Vilnius, Kreva, Navahrudak and Minsk (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 161

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). From the second half of the 14th century the Tatar settlement was developed mainly in the area Trakai and Vilnius - the strategic military centres (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 209

). From the second half of the 14th century the Tatar settlement was developed mainly in the area Trakai and Vilnius - the strategic military centres (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 209 Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). The Tatars who arrived to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were given a land for perpetual lease, in return for the military service in the Lithuanian army but funded by themselves. The conditions were still favourable for the Tatars and the first wave of settlers was followed by others. The settlements reached its peak in the 16th c. The numbers concerning the Tatars on the Polish territory in that time are estimated between 40 and 200 thousands (Łapicz 1986: 29

). The Tatars who arrived to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were given a land for perpetual lease, in return for the military service in the Lithuanian army but funded by themselves. The conditions were still favourable for the Tatars and the first wave of settlers was followed by others. The settlements reached its peak in the 16th c. The numbers concerning the Tatars on the Polish territory in that time are estimated between 40 and 200 thousands (Łapicz 1986: 29 Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Łapicz, Czesław 1986. Kitab Tatarów litewsko-polskich (Paleografia. Grafia. Język). Toruń: UMK.

).

).The Lithuanian and Polish Tatars never were a homogeneous social group, as a consequence of social differences, as well as, relatively big territorial dispersion. Despite the so-called farming Tatars that is the Tatar noble landowners, members of which served in the Lithuanian and Polish army; a great percentage of the Tatar settlers belonged to the poorer strata - the burghers (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 201

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). There are few references in historical sources about the latter; especially in the second half of the 17th c., when economic regression occurred and people stopped founding cities on a big scale, the historians’ attention was focused mainly on the Tatar landed gentry (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 213

). There are few references in historical sources about the latter; especially in the second half of the 17th c., when economic regression occurred and people stopped founding cities on a big scale, the historians’ attention was focused mainly on the Tatar landed gentry (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 213 Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). Differently than other minorities, the Tatar middle-class did not form communes - in some cities there were only Tatar streets (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 214

). Differently than other minorities, the Tatar middle-class did not form communes - in some cities there were only Tatar streets (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 214 Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). The percentage of Tatar population on a given area was always small, and the Tatars themselves assimilated easily. It was even easier, because in the period when the Tatar-Lithuanian middle class formed (the 17th - first half of the 18th c.) those people were already speaking Polish and/or Ruthenian.

). The percentage of Tatar population on a given area was always small, and the Tatars themselves assimilated easily. It was even easier, because in the period when the Tatar-Lithuanian middle class formed (the 17th - first half of the 18th c.) those people were already speaking Polish and/or Ruthenian.The flow of people between the landed gentry and the burghers among the 17th and the 18th century Polish-Lithuanian Tatars, was more frequent than among other minorities. The beginning of the 17th c. was the time when the Tatar landed gentry begun to declass, and their patrimony was divided and lost.The wars between 1648 and 1672 caused big loss in property and casualties. The Tatar property passed to the Lithuanian nobility, and the Tatars successively moved to cities. Descendants of this group formed, up to the first quarter of the 20th c., the basis of the urban proletariat and the Tatar intelligentsia (Tyszkiewicz 1989: 217-218

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r /

Tyszkiewicz 1989 / komentarz/comment/r / Tyszkiewicz, Jan 1989. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejów XIII – XVIII w. Warszawa: PWN.

). With the end of the I World War, Tatars became the citizens of three countries: independent Lithuania, Poland and the USRR, and after the II World War ended, part of the Tatar repatriates in Poland inhabited the area on which the Tatars had never lived before: Gdansk, Wroclaw, Górzów Wielkopolski (Łapicz 1986: 21

). With the end of the I World War, Tatars became the citizens of three countries: independent Lithuania, Poland and the USRR, and after the II World War ended, part of the Tatar repatriates in Poland inhabited the area on which the Tatars had never lived before: Gdansk, Wroclaw, Górzów Wielkopolski (Łapicz 1986: 21 Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Łapicz, Czesław 1986. Kitab Tatarów litewsko-polskich (Paleografia. Grafia. Język). Toruń: UMK.

).

).

ISO Code

ISO 639-3 / SIL for Tatar: tat

(Lewis 2009: 571 Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis, Paul M. (ed.) 2009. Ethnologue: languages of the world. 16th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

)

)

Crimean Tatar: crh

(Lewis 2009: 571

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, Paul M. (ed.) 2009. Ethnologue: languages of the world. 16th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

)

)Crimean Tatar: crh

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- tekst ustawy w języku krymsko-tatarskim

- Lewis 2009

- Tyszkiewicz 1989

- Jankowski 1997

- Berta 2006

- Łapicz 1986

- Boeschoten 2006

- Kamocki 1993

- Warmińska 1999

- Stachowski 2007

- Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000

- Chazbijewicz 1994

- Miškiniene 2000

- Chazbijewicz 1995

- Jankowski 2010

- Kryczyński 1938

- Lewis 2006

- Grenoble – Whaley 2006

- Rykała 2011

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- ilustr02

- ilustr03

- ilustr04

- ilustr05

- ilustr06

- ilustr07

- mapa języków ałtajskich i uralskich

- Tatarzy i ich sąsiedzi w XIII-XV w