Tatar

Tatar writings

The history of Tatar writings

Risale-i Tatar-i Lex (Treaty about the Polish Tatars) from 1558 is considered to be the first written material of the Polish-Lithuanian Tatars. The text source for the Polish translators Antoni Muchlinski from 1858 was - according to him- a manuscript from Istanbul, history of which is unknown. The 19th c. stylistics and lexicon of the translation allows us to doubt the authenticity, or even the existence of the original text (Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000: 16-17 Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

). The Tatar Apology from 1630 is the first printed text, ascribed to the Tatars. (Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000: 34

). The Tatar Apology from 1630 is the first printed text, ascribed to the Tatars. (Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000: 34 Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

).

).The beginning of the Polish-Lithuanian Tatars’ writing dates back to the period when the Tatar language had already died out. There is no writing relic, which would consist of continuous texts written in the ethnic Tatar language (Łapicz 1986: 39

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Łapicz, Czesław 1986. Kitab Tatarów litewsko-polskich (Paleografia. Grafia. Język). Toruń: UMK.

). To maintain the connection with their own cultural heritage, Polish-Lithuanian Tatars started to write down religious texts, as they were to be ultimately available to a wide audience, there had to be translated into the languages commonly known to the Tatars: Polish and Belarusian.

). To maintain the connection with their own cultural heritage, Polish-Lithuanian Tatars started to write down religious texts, as they were to be ultimately available to a wide audience, there had to be translated into the languages commonly known to the Tatars: Polish and Belarusian.Arabic was the language of religious writing and religious practices of the Tatars. Initially, no other language was acceptable in liturgy, but in the course of time, Turkish started to be used. What is interesting, the Arabic texts were mostly translated into Belarusian, and the Turkish texts into Polish. This was related to the prestige which was associated with those languages.

The Tatars created religious themes texts: kitabs, tesfirs, chamails and others. In 1836 a dictionary was created. It consisted of a thousand Turkic and Moldavian words with the Polish and Belarusian translations. It was one of two lexicographical attempts of the Polish-Belarusian Tatars, which survived to the present day. The second one was a dictionary in kitab from 1866, about the same volume (Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000: 15

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

). The history of cultural and literary activity of the Tatars does not report any publishing attempts in Tatar (c.f. Chazbijewicz 1994

). The history of cultural and literary activity of the Tatars does not report any publishing attempts in Tatar (c.f. Chazbijewicz 1994 Chazbijewicz 1994 / komentarz/comment/r /

Chazbijewicz 1994 / komentarz/comment/r / Chazbijewicz, Selim 1994. "Kultura literacka Tatarów polskich", Rocznik Tatarów Polskich. Tom II. Gdańsk: Związek Tatarów Polskich, s. 240-247.

).

). Tatar religious texts

Kitabs were the basic carrier of the literary heritage (and cultural) of the Polish-Lithuanian Tatars. They were books, which intertwined the Koran threads, commentaries to the Koranic Suras, Islamic tales, often based on the historical authorities, didactic texts rarely about non-religious issues (Miškiniene 2000: 33 Miškiniene 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Miškiniene 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Miškiniene, Halina 2000. "O zawartości treściowej najstarszych rękopisów Tatarów litewskich", Rocznik Tatarów Polskich. Tom VI. Gdańsk: Związek Tatarów Polskich, s. 30-35.

). In the 19th and 20th c. there was one kitab for a few or even a few dozen Tatar families. The oldest one - Kitab from Suchowola - dates back to 1631. (Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000: 20

). In the 19th and 20th c. there was one kitab for a few or even a few dozen Tatar families. The oldest one - Kitab from Suchowola - dates back to 1631. (Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000: 20 Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

).

).Kitabs were always multilingual: they were written in Belarusian, Polish, Arabic and Turkic; the oldest ones in Arabic and Ruthenian. Belarusian and Polish in Kitab texts did not appear in their literary forms, the dialectal influences were noticeable. Frequently, the language of commentaries and footnotes for Kitabs was the transitory local Polish-Belarusian dialect, with different number of features from one language or the other.

The Kitabs’ language was different from the spoken language, even if only by the religious character of the books (Łapicz 1986: 217-220

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łapicz 1986 / komentarz/comment/r / Łapicz, Czesław 1986. Kitab Tatarów litewsko-polskich (Paleografia. Grafia. Język). Toruń: UMK.

).

). Apart from Kitabs and Koran manuscripts, the Tatars created Tesfirs - books which comprised of prayers and commentaries in form of fragments from Koran with the Polish translation written diagonally between the verses.

Apart from Tesfirs, they also created Khamails - prayer books, which apart from their ritual character also had the magical and medicinal purpose.

They described the Muslim ritual, set of prayers, Muslim calendar, but also e.g. magical-healing formulas.

There were also auxiliary texts - Tadzvid (written in Turkic along with interlinear Polish-Belarusian translation, lectures about Koran recitation) and Sufras (manuscipts which comprises of 1/30 of the Koran book).

Some Tatar manuscripts also served as talismans: various types of prayer scrolls were put in the grave with the deceased or carried as objects - as they were to bring prosperity and protect from misfortunes.

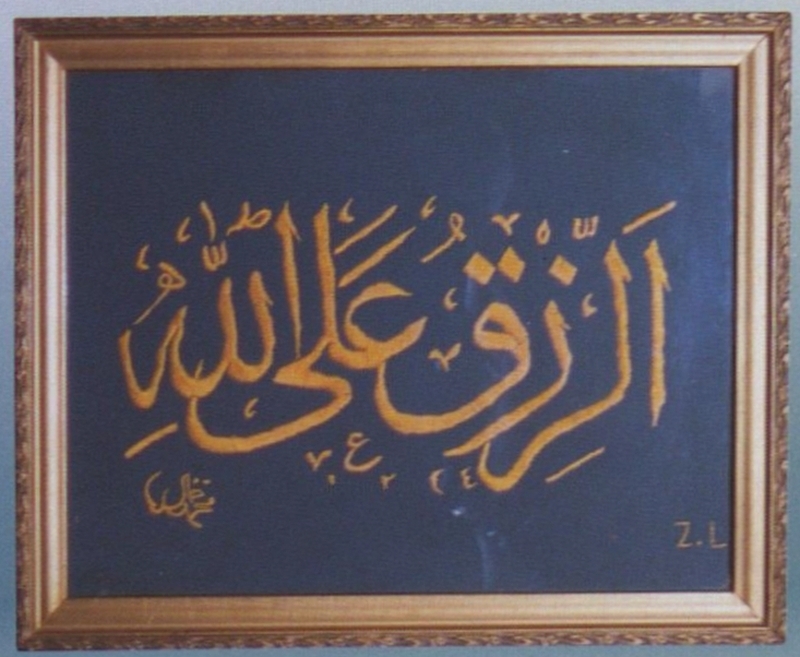

The Tatar form between writing, painting and handicrafts are the so-called Muhirs - boards hung on the walls.

Other texts

Tatars aim at creating publications which would unite and strengthen the Tatar community. It is done mainly in a religious context (e.g. Muslim Calendar published in the interwar period), but not only.Chazbijewicz (1995

Chazbijewicz 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Chazbijewicz 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Chazbijewicz, Selim 1995. "Prasa tatarsko-muzułmańska w Polsce w latach 1939-1996", Rocznik Tatarów Polskich. Tom III. Gdańsk – Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, s. 87-102.

) pays a lot of attention to all kinds of Tatar magazines: the magazine Tatar Life was published in years 1934-39 in Vilnius, and Muslim Life in years 1985-91. At present, the Tatar community is united by the Polish Tatars Annual published since 1993.

) pays a lot of attention to all kinds of Tatar magazines: the magazine Tatar Life was published in years 1934-39 in Vilnius, and Muslim Life in years 1985-91. At present, the Tatar community is united by the Polish Tatars Annual published since 1993.Examples of texts

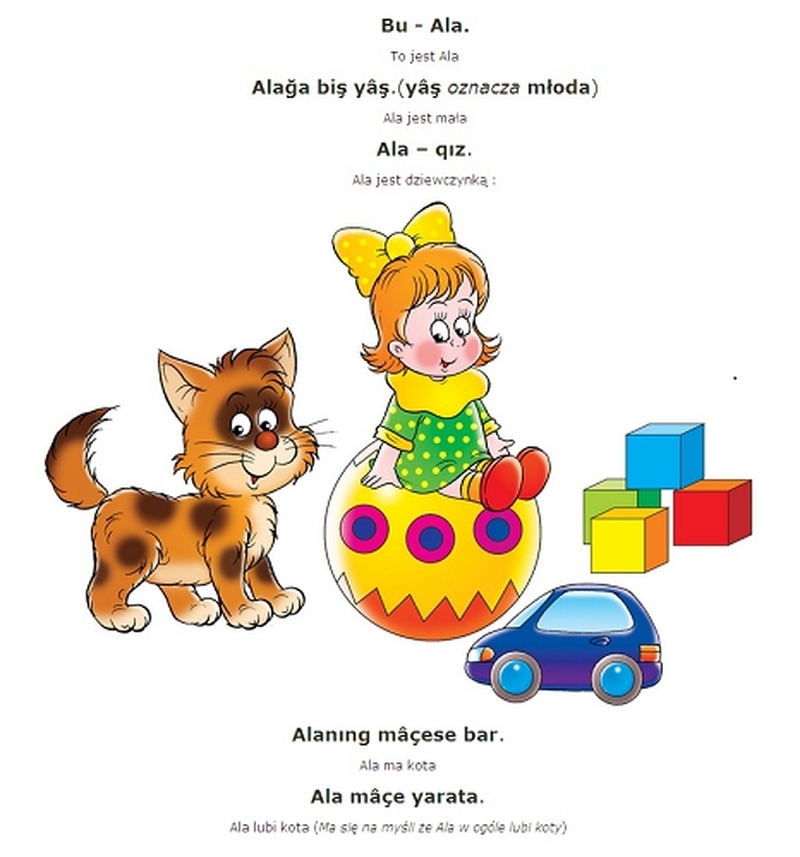

Examples of texts presented below are, for the reasons mentioned several times, examples of the texts written in languages other than Tatar, but used by the Tatar community in everyday life (Polish and Belarusian), or restricted for a religious purpose (Turkic and Arabic).The only example of the text in Tatar is the fragment adapted for the learning purpose: a primal with the commentaries in Polish, which was compiled from the materials for the Tatar learning with TAT code.

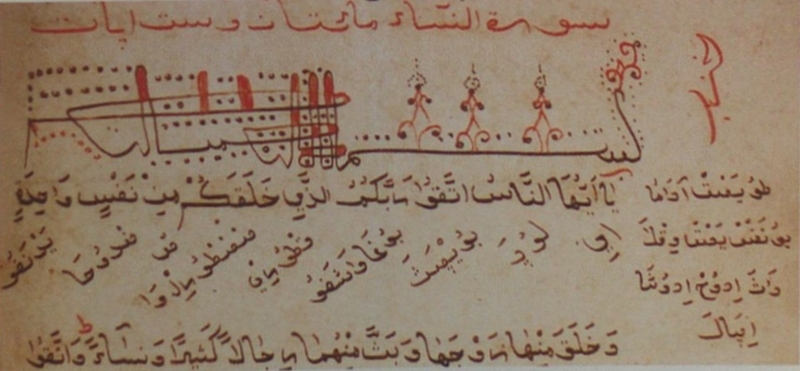

Tesfir from 1725. A page with the text 43. Koran suras, ornaments in the Arabic language (source: Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

).

).

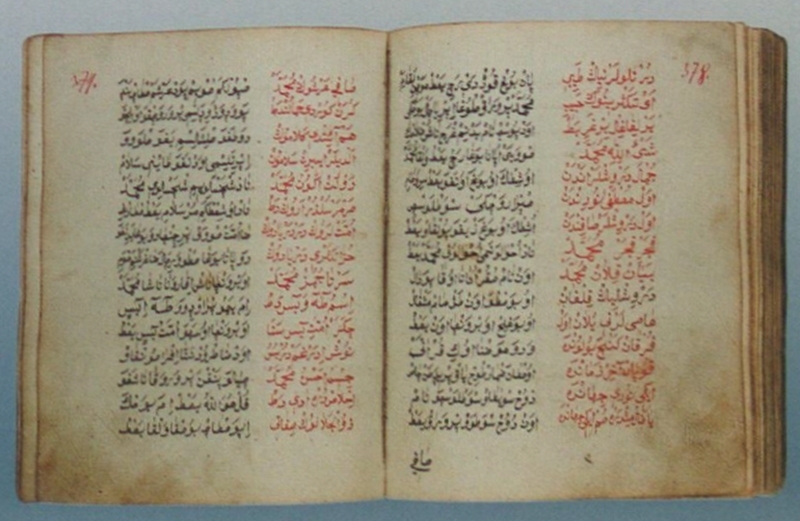

Kitab from Slonim from 1837 with a text of prayer in Turkic with a parallel translation into Polish (source: Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000).

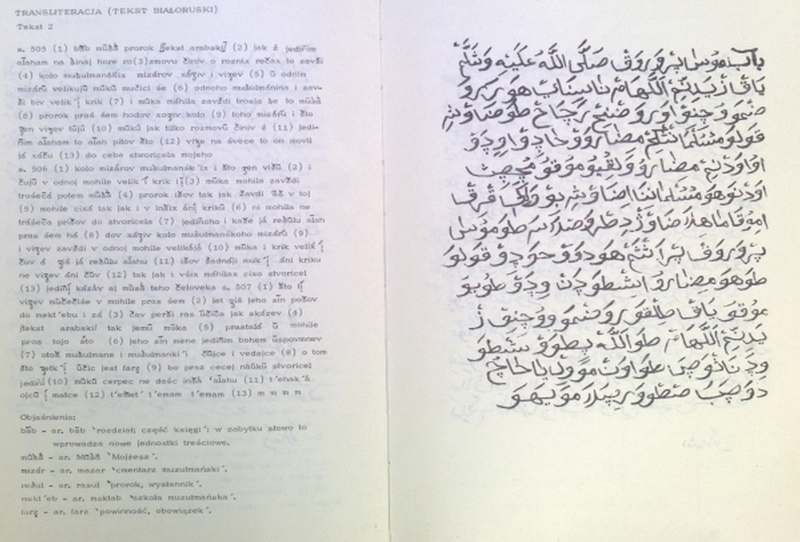

Tale about Moses conversation with Allah in Belarusian with few Polish interpolation, along with Belarusian transliteration (source: Łapicz 1986: 228-229).

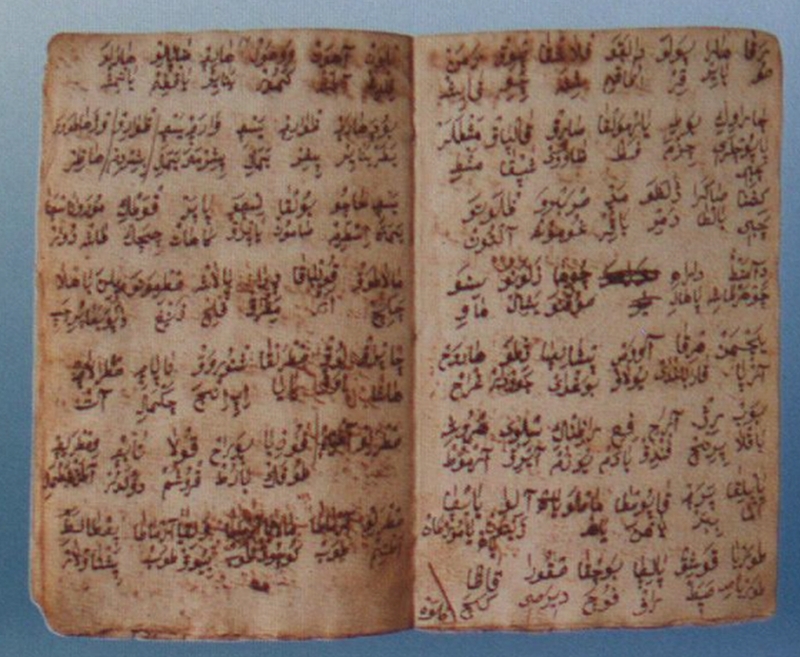

Turkish-Balarusian-Polish dictionary from 1836 (source: Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

).

).

Muhir with a calligraphic inscription from around the second half of the 20th century (source: Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Drozd, Andrzej & Marek M. Dziekan & Tadeusz Majda 2000. Piśmiennictwo i Muhiry Tatarów polsko-litewskich. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica.

).

).

Fragments from a Tatar primer (source: www.tataria.eu).

ISO Code

ISO 639-3 / SIL for Tatar: tat

(Lewis 2009: 571 Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis, Paul M. (ed.) 2009. Ethnologue: languages of the world. 16th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

)

)

Crimean Tatar: crh

(Lewis 2009: 571

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, Paul M. (ed.) 2009. Ethnologue: languages of the world. 16th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

)

)Crimean Tatar: crh

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- tekst ustawy w języku krymsko-tatarskim

- Lewis 2009

- Tyszkiewicz 1989

- Jankowski 1997

- Berta 2006

- Łapicz 1986

- Boeschoten 2006

- Kamocki 1993

- Warmińska 1999

- Stachowski 2007

- Drozd – Dziekan – Majda 2000

- Chazbijewicz 1994

- Miškiniene 2000

- Chazbijewicz 1995

- Jankowski 2010

- Kryczyński 1938

- Lewis 2006

- Grenoble – Whaley 2006

- Rykała 2011

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- ilustr02

- ilustr03

- ilustr04

- ilustr05

- ilustr06

- ilustr07

- mapa języków ałtajskich i uralskich

- Tatarzy i ich sąsiedzi w XIII-XV w