wilamowski

Wprowadzenie

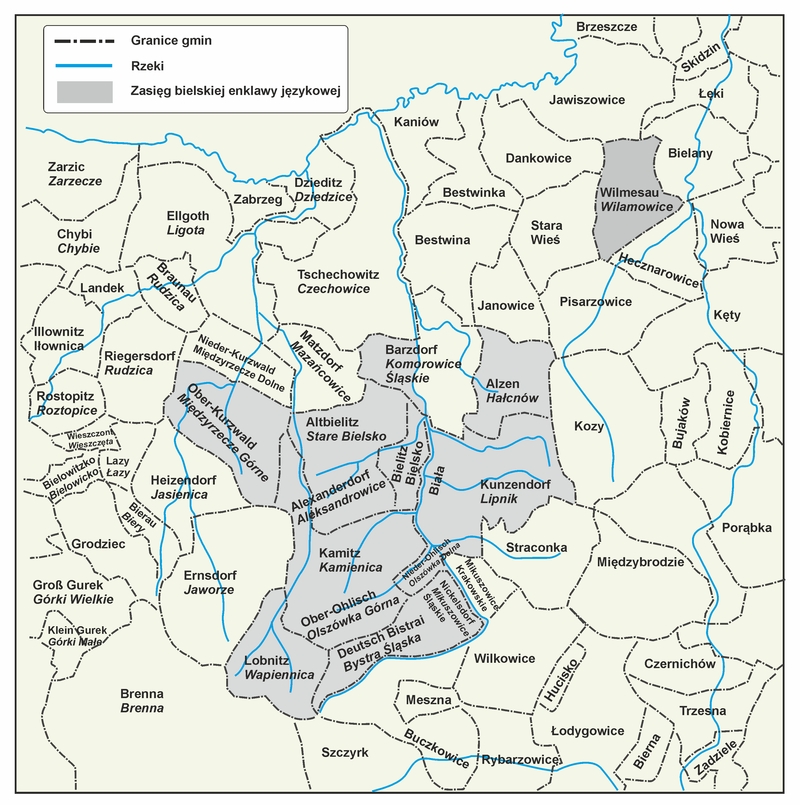

Terminem „bielsko-bialska wyspa językowa” (Bielitz-Bialaer Sprachinsel) uczeni niemieccy określali szereg miejscowości leżących wokół leżącego na Śląsku Cieszyńskim Bielska i małopolskiej Białej. Większość mieszkańców tych miejscowości do II wojny światowej posługiwała się językiem niemieckim.Według niemieckich badaczy, tuż przed drugą wojną światową po śląskiej stronie wyspę językową oprócz samego Bielska tworzyły:

• Międzyrzecze Górne (Ober-Kurzwald),

• Komorowice Śląskie (Batzdorf),

• Kamienica (Kamitz),

• Wapienica (Lobnitz),

• Bystra Śląska (Deutsch-Bistrai),

• Aleksandrowice (Alexanderfeld),

• Mikuszowice (Nickelsdorf),

• Olszówka Górna (Ober-Ohlish),

• Olszówka Dolna (Nieder-Ohlish) oraz

• Stare Bielsko (Altbielitz).

Po drugiej stronie rzeki Białej, obok miejscowości o tej samej co rzeka nazwie, do wyspy włączano również:

• Lipnik (Kunzendorf),

• Hałcnów (Alzen ) oraz

• Wilamowice (Wilmesau).

Sami mieszkańcy Wilamowic nie uważają jednak siebie za Niemców. Uwzględniając tę opinię, ale i mając wzgląd na pewne podobieństwa językowe między językiem wilamowskim a dialektami używanymi w innych wymienionych miejscowościach w pracy tej używane będzie sformułowanie: bielsko-bialska niemiecka wyspa językowa i Wilamowice. W zależności od kontekstu użyte zostaną nazwy poszczególnych miejscowości w języku polskim lub standardowym niemieckim.

Nazwy

Lingwonimy

Endolingwonimy

Większość mieszkańców miast i wsi wchodzących w skład tak zwanej bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej miała zapewne świadomość, że odmiany językowe, którymi mówili różniły się od standardowej wersji języka niemieckiego (Hochdeutsch). Swoją mowę określali często jako „chłopską”. W Bielsku i Białej używano do tego słowa pauerisch(e) (Bock 1916a: 220 Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment /

Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment / Bock Friedrich 1916b. Der Liega-Jirg. Gedicht in der Bielitzer Mundart. Bielitz: Friedrich Bock. [przedruk w: Wagner 1936: 222-230].

), w Hałcnowie päuersch.

), w Hałcnowie päuersch.Tylko w dwóch omawianych miejscowościach wykształciły się nazwy określające używane w nich odmiany językowe. Hałcnowianie swoją mowę określali jako aljzjnerisch lub aljznerisch. Użytkownicy języka wilamowskiego nazywają go wymysiöeryś. Taki stan rzeczy mógł wynikać z peryferyjnego położenia tych miejscowości, a przede wszystkim większej niż gdzie indziej odrębności językowej.

Historia i geopolityka

Lokalizacja

Termin ‘bielsko-bialska niemiecka wyspa językowa’ powstał na przełomie XIX i XX wieku. Mianem tym określano miasta Bielsko i Białą oraz położone wokół nich miejscowości, w których większość mieszkańców posługiwała się niemieckimi dialektami. Stosunki etniczne i językowe ulegają ciągłym zmianom, zatem i kształt bielskiej wyspy językowej ulegać musiał przekształceniom.Jedną z prób określenia jej granic podjął niemiecki badacz Gerhard Wurbs (1981: 84, 85

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Wyróżnił on trzy grupy miejscowości. Do pierwszej z nich zaliczył te, które do 1945 roku zachowały swój niemiecki charakter. Są to:

). Wyróżnił on trzy grupy miejscowości. Do pierwszej z nich zaliczył te, które do 1945 roku zachowały swój niemiecki charakter. Są to:- Bielsko (Bielitz)

- Biała (Biala)

- Lipnik (Kunzendorf)

- Hałcnów (Alzen)

- Wilamowice (Wilmesau)

- Komorowice Śląskie (Batzdorf)

- Międzyrzecze Górne (Ober Kurzwald)

- Wapienica (Lobnitz)

- Stare Bielsko (Altbielitz)

- Aleksandrowice (Alexanderfeld)

- Kamienica (Kamitz)

- Olszówka (Ohlisch)

- Bystra (Bistrai)

- Mikuszowice Śląskie (Nickelsdorf)

- Jasienica (Heinzendorf)

- Jaworze (Ernsdorf)

- Bystra Krakowska (Bistrai-Süd)

- Mikuszowice Krakowskie (Mikuschowitz)

- Straconka (Dresseldorf)

- Kozy (Seibersdorf)

- Pisarzowice (Schreibersdorf)

- Stara Wieś (Altdorf)

- Komorowice Krakowskie (Mückendorf[1

przyp01 / komentarz/comment /

przyp01 / komentarz/comment /

Mückendorf był częścią Komorowic włączoną później do Czechowic. Miejscowość oznaczona na mapie przez Wurbsa jako 24, to Komorowice Krakowskie, które pierwotnie nosiły nazwę Batzdorf lub Bertoltowitz. Nazwa Komorowice jest późniejsza. Powstała ona jako kalka językowa z języka niemieckiego (die Mücke = komar). Z czasem w języku polskim nazwą Komorowice zaczęto określać zarówno Mückendorf, jak i Batzdorf/Bertoltowitz. ])

]) - Mazańcowice (Matzdorf)

- Landek (Landeck)

- Bronów (Braunau)

- Wilkowice (Wilkowitz)

- Łodygowice (Lodygowitz)

- Kęty (Liebenwerde, też Liewerdt)

- Nowa Wieś (Neudorf)

- Nidek (Nydek)

- Dankowice (Denkendorf)

Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment / Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.

, Wicherkiewicz 2001

, Wicherkiewicz 2001 Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2001. „Piśmiennictwo w etnolekcie wilamowskim”, w: Barciak 2001: 520-538.

, Wicherkiewicz 2003

, Wicherkiewicz 2003 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

). Józef Latosiński, historyk amator, autor Monografii Miasteczka Wilamowic, pisał, że:

). Józef Latosiński, historyk amator, autor Monografii Miasteczka Wilamowic, pisał, że: Oprócz Wilamowic i Starejwsi, powstały w tych czasach następujące niemieckie osady w ziemi oświęcimskiej: Pisarzowice (Schreibersdorf), Kęty (Liebenwerde), Kozy (Seubersdorf)[2Przed 1918 rokiem wielu mieszkańców opisywanych terenów podejmowało pracę na terenie państwa, którego byli obywatelami, czyli Cesarstwa Austro-Węgierskiego. Większość z nich zapewne szybko przystosowywała się pod względem językowym do nowego otoczenia. Warto zauważyć, że najważniejsze dzieła literackie w języku wilamowskim powstawały w Trieście. Wilamowianie[3przyp02 / komentarz/comment /

Niemiecka nazwa Kóz to wg większości źródeł Seibersdorf.], Hałcnów (Alzen), Lipnik (Kunzendorf), Komorowice (Bertholdsdorf), Łodygowice (Ludwigsdorf), Inwałd (Hinwald), Barwałd (Bärenwald) i inne.

przyp03 / komentarz/comment /

przyp03 / komentarz/comment / Z wyjątkiem cytatów wyraz „Wilamowianie” pisano z wielkiej litery, jako że odnosi się ono nie tyle do mieszkańców miejscowości, co do członków grupy etnojęzykowej.

], którzy dość licznie osiedlali się w Wiedniu, będąc na emigracji przez długi czas zachowywali swoją odrębność i utrzymywali kontakty z miejscem pochodzenia (Filip 2005

], którzy dość licznie osiedlali się w Wiedniu, będąc na emigracji przez długi czas zachowywali swoją odrębność i utrzymywali kontakty z miejscem pochodzenia (Filip 2005 Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment / Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.

, Wicherkiewicz 2003

, Wicherkiewicz 2003 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

).

).

Bielsko-bialska wyspa językowa na tle przedwojennej (↑) i obecnej (↓) siatki administracyjnej miejscowości - red.mapy Jacek Cieślewicz.

Historia i geneza

Granica między Śląskiem a Małopolską

Obszary, na których leży dziś Bielsko-Biała i otaczające je wioski, przez bardzo długi czas pozostawały praktycznie bezludne. Jeszcze w czasie tworzenia się państwowości polskiej okolica ta stanowiła pusty obszar rozgraniczający ziemie dwóch słowiańskich plemion Gołęszyców na zachodzie i Wiślan na wschodzie (Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b: 119 Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010b. „Początki Bielska”, w: Panic 2010:141-159.

). W XI wieku w niedalekiej odległości od tego miejsca powstały dwa grody Cieszyn i Oświęcim, które stały się siedzibami jednostek administracyjnych - kasztelanii. Granica między nimi przebiegała na Białce, rzece płynącej przez środek Bielska-Białej, dzieląc miasto na dwie części. Granicę tę zaadaptowała również administracja kościelna. Terytorium leżące na zachód od rzeki Białki weszło w skład diecezji wrocławskiej, natomiast tereny znajdujące się na drugim brzegu rzeki podlegały biskupowi krakowskiemu. Podział ten okazał się zaskakująco trwały i z wyjątkiem okresu, o którym później, formalnie utrzymał się on aż do XX wieku, a w świadomości mieszkańców regionu istnieje do tej pory.

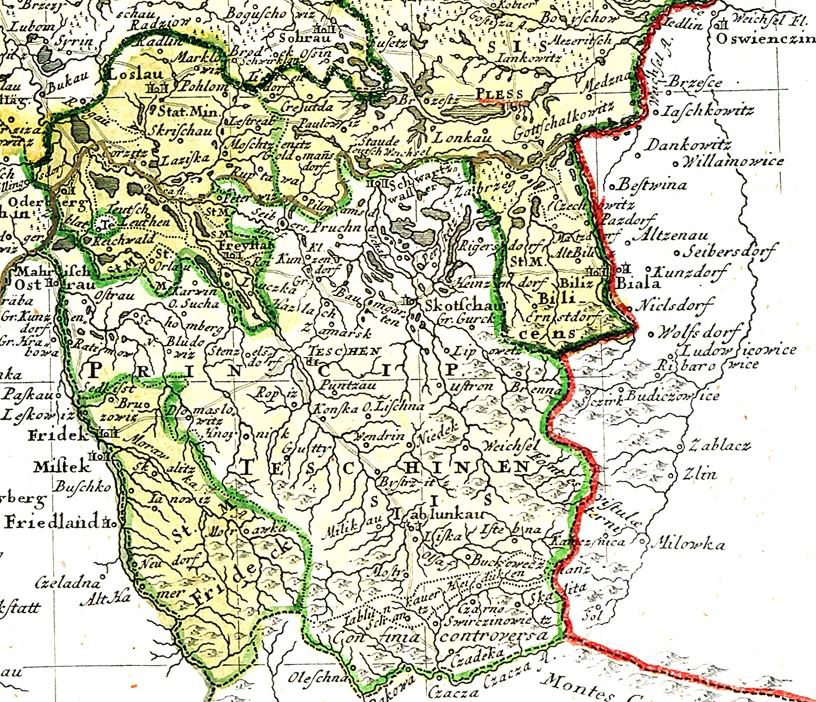

). W XI wieku w niedalekiej odległości od tego miejsca powstały dwa grody Cieszyn i Oświęcim, które stały się siedzibami jednostek administracyjnych - kasztelanii. Granica między nimi przebiegała na Białce, rzece płynącej przez środek Bielska-Białej, dzieląc miasto na dwie części. Granicę tę zaadaptowała również administracja kościelna. Terytorium leżące na zachód od rzeki Białki weszło w skład diecezji wrocławskiej, natomiast tereny znajdujące się na drugim brzegu rzeki podlegały biskupowi krakowskiemu. Podział ten okazał się zaskakująco trwały i z wyjątkiem okresu, o którym później, formalnie utrzymał się on aż do XX wieku, a w świadomości mieszkańców regionu istnieje do tej pory. Ziemia oświęcimska i ziemia cieszyńska w średniowieczu

Ziemia oświęcimska, w skład której wchodziła wschodnia część bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej zmieniła władcę, a co za tym idzie również przynależność dzielnicową, w 1179 roku. Wtedy to z okazji chrztu syna Mieszka Plątonogiego Kazimierz Sprawiedliwy przekazał mu kasztelanię oświęcimską i bytomską. W ten sposób ten pierwszy stał się władcą rozległego terytorium, obejmującego ziemię raciborską, oświęcimską, opolską i cieszyńską (Putek 1938: 1 Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

). Całość terytorium, które później wejdzie w skład bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej, na prawie 140 lat, stało się częścią tej samej jednostki administracyjnej, która jednak stale, na mocy testamentów ulegała podziałom. W 1290 roku wyodrębniło się księstwo cieszyńskie, w skład którego wchodziła również ziemia oświęcimska, zatorska i chrzanowska. Jego władcą został Mieszko. Po jego śmierci w 1316 roku doszło do dalszych podziałów, w efekcie których powstało osobne księstwo oświęcimskie. W jego skład weszła cała część bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej położona na wschód od rzeki Białej (Putek 1938: 2

). Całość terytorium, które później wejdzie w skład bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej, na prawie 140 lat, stało się częścią tej samej jednostki administracyjnej, która jednak stale, na mocy testamentów ulegała podziałom. W 1290 roku wyodrębniło się księstwo cieszyńskie, w skład którego wchodziła również ziemia oświęcimska, zatorska i chrzanowska. Jego władcą został Mieszko. Po jego śmierci w 1316 roku doszło do dalszych podziałów, w efekcie których powstało osobne księstwo oświęcimskie. W jego skład weszła cała część bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej położona na wschód od rzeki Białej (Putek 1938: 2 Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

; Wurbs 1981: 11

; Wurbs 1981: 11 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

).

).

Księstwo cieszyńskie w roku 1746, za: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:Principatus_Teschinenis_Superiorem_Silesiam_AD1746.jpg

Z czasem rozluźniły się więzy między Piastami cieszyńskimi i oświęcimskimi, a polskim władcą senioralnym, który zasiadał na tronie w Krakowie. Część z książąt usiłowała zachować polityczną niezależność, jednakże niektórzy złożyli hołd lenny królom czeskim, przez co stawali się ich wasalami. Związki polityczne z Polską ostatecznie ustały w 1335 roku, kiedy to na mocy traktatu trenczyńskiego król Kazimierz Wielki zrzekł się roszczeń polskich do księstw śląskich, w tym także cieszyńskiego i oświęcimskiego. To drugie, wraz z Białą i okolicznymi wsiami wróciło do Polski w 1453 roku, natomiast położone między Olzą a Białą tereny ówczesnego Księstwa Cieszyńskiego wraz z Bielskiem zostały oficjalnie przyłączone do Rzeczypospolitej dopiero w 1920 roku.

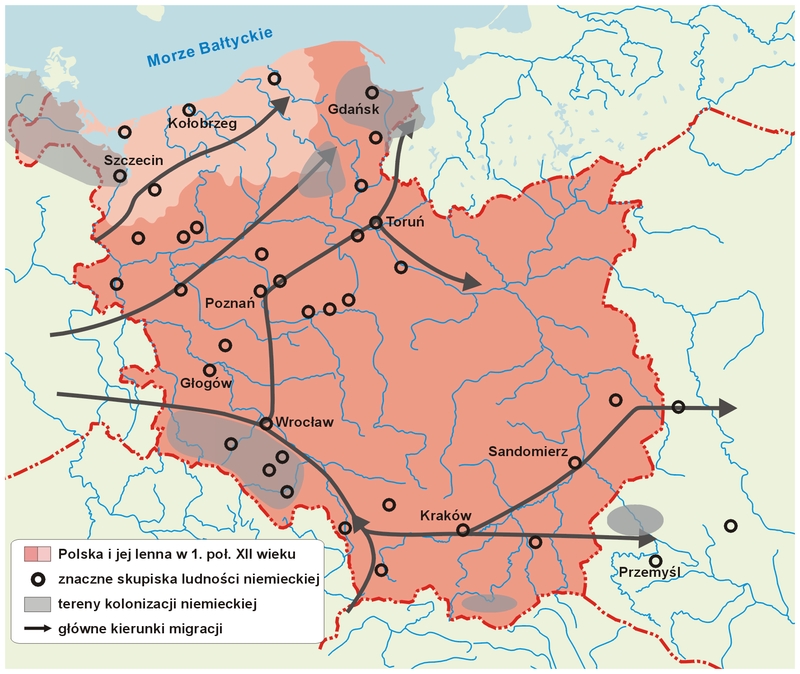

Procesy kolonizacyjne – powstawanie miejscowości

Proces tworzenia się coraz mniejszych księstw miał dla powstania późniejszej odrębności językowej ogromne znaczenie. W związku z kurczeniem się obszarów, którymi rządzili poszczególni władcy, spadały ich dochody. Jedynym sposobem na ich zwiększenie było zapraszanie na niezamieszkałe tereny kolonistów, których daniny (wpłacane po okresie zwolnienia z podatku - wolnizny) pozwalały poprawić stan książęcych finansów (Putek 1938: 25 Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

). Naturalnym wydałoby się sprowadzenie osadników z sąsiednich części Polski, jednak i tak szczupłe zasoby ludzkie, ograniczone zostały tam w dramatyczny sposób przez najazdy tatarskie. Dlatego też piastowscy książęta śląscy oraz uposażeni przez nich dworzanie, urzędnicy i rycerze zaczęli również sprowadzać na swe ziemie kolonistów z przeludnionych obszarów niemieckojęzycznych.

). Naturalnym wydałoby się sprowadzenie osadników z sąsiednich części Polski, jednak i tak szczupłe zasoby ludzkie, ograniczone zostały tam w dramatyczny sposób przez najazdy tatarskie. Dlatego też piastowscy książęta śląscy oraz uposażeni przez nich dworzanie, urzędnicy i rycerze zaczęli również sprowadzać na swe ziemie kolonistów z przeludnionych obszarów niemieckojęzycznych.

Kolonizacja niemiecka w średniowieczu - red.mapy Jacek Cieślewicz

Kolonizacja na szerszą skalę zaczęła się w latach 1230-tych; założone zostało m.in Wilhelmsdorf, czy też Antiquo Wilamowicz - obecna Stara Wieś. W późniejszym okresie, ale jeszcze przed 1325 rokiem część mieszkańców tej osady przeniosła się kilka kilometrów dalej i zasiedliła Wilamowice (Barciak 2001: 82, 85

Barciak 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Barciak 2001 / komentarz/comment / Barciak, Antorni (red.) 2001. Wilamowice. Przyroda, historia, język, kultura, oraz społeczeństwo miasta i gminy. Wilamowice: Urząd Gminy.

).

). W ten sposób zakończyła się pierwsza fala kolonizacyjna. Kolejne miejscowości powstawały dopiero po około 100 latach.

Historia wschodniej części wyspy językowej – średniowiecze i nowożytność

Przez długi czas najważniejszą osadą położoną na wschodnim brzegu rzeki Białej był założony jeszcze w średniowieczu Lipnik (Kunzendorf). Osada ta była siedzibą starostwa niegrodowego. Stanowiła ona własność różnych rodzin szlacheckich (Polak 2010: 26 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). Pierwsze wzmianki dotyczące Białej są stosunkowo późne, bo pochodzą z 1564 roku (Wurbs 1981: 83

). Pierwsze wzmianki dotyczące Białej są stosunkowo późne, bo pochodzą z 1564 roku (Wurbs 1981: 83 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Całą miejscowość stanowiło wtedy kilkanaście zabudowań. Pierwszymi osadnikami byli zapewne rzemieślnicy pochodzący z sąsiedniego Bielska. Po zakończeniu wojny trzydziestoletniej (1618-1648) do tej nadgranicznej miejscowości ściągnęło wielu protestantów ze Śląska, uciekających przed prześladowaniami. Rzemieślnicy z Białej nie byli ograniczeni prawem cechowym, toteż mogli dostarczać na rynek tańsze produkty. Taka działalność na granicy prawa przyczyniła się do rozwoju miejscowości, której w roku 1723 na mocy decyzji Augusta II przyznano prawa miejskie. Biała z czasem przeszła na własność królewską (Polak 2010: 104

). Całą miejscowość stanowiło wtedy kilkanaście zabudowań. Pierwszymi osadnikami byli zapewne rzemieślnicy pochodzący z sąsiedniego Bielska. Po zakończeniu wojny trzydziestoletniej (1618-1648) do tej nadgranicznej miejscowości ściągnęło wielu protestantów ze Śląska, uciekających przed prześladowaniami. Rzemieślnicy z Białej nie byli ograniczeni prawem cechowym, toteż mogli dostarczać na rynek tańsze produkty. Taka działalność na granicy prawa przyczyniła się do rozwoju miejscowości, której w roku 1723 na mocy decyzji Augusta II przyznano prawa miejskie. Biała z czasem przeszła na własność królewską (Polak 2010: 104 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

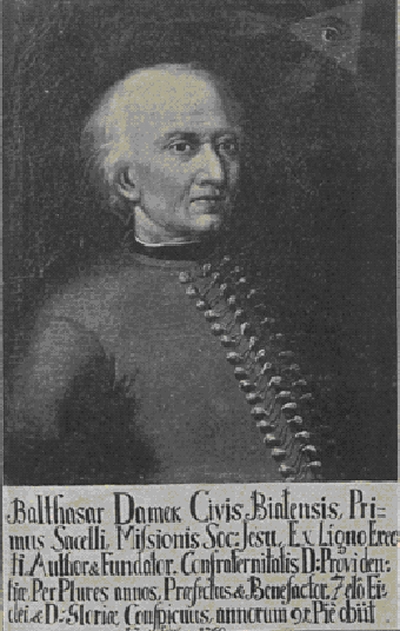

). Jej pierwszym burmistrzem został Baltazar Damek. Był on patronem katolicyzmu, bankierem (lub może lichwiarzem) i pierwszym mecenasem sztuki w mieście. Jerzy Polak przypuszcza, że był on „spolonizowanym wilamowiczaninem” (Polak 2010: 89, 104, 113, 115

). Jej pierwszym burmistrzem został Baltazar Damek. Był on patronem katolicyzmu, bankierem (lub może lichwiarzem) i pierwszym mecenasem sztuki w mieście. Jerzy Polak przypuszcza, że był on „spolonizowanym wilamowiczaninem” (Polak 2010: 89, 104, 113, 115 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). W 1772 roku w wyniku pierwszego rozbioru Polski tereny Księstwa Oświęcimskiego zostały przyłączone do Austrii. Początkowo nie weszły jednak w skład Galicji.

). W 1772 roku w wyniku pierwszego rozbioru Polski tereny Księstwa Oświęcimskiego zostały przyłączone do Austrii. Początkowo nie weszły jednak w skład Galicji.

Baltazar Damek (za: Hanslik 1908: 97

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin, 1908. Biala, eine deutsche Stadt in Galizien. Wien-Teschen-Leipzig.

)

)Rozwój przemysłu

Do Bielska, Białej, a także okolicznych miejscowości, w których również bardzo intensywnie rozwijał się przemysł, ściągały tysiące ludzi z Austrii, Moraw, pruskiego Śląska, Galicji. Pod koniec XIX wieku ponad połowę mieszkańców Bielska stanowią przyjezdni (Spyra 2010: 139 Spyra 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Spyra 2010 / komentarz/comment / Spyra, Janusz 2010. ”Przeobrażenia struktur społecznych i narodowościowych w Bielsku w drugiej połowie XIX i początkach XX wieku, w: Spyra i Kenig 2010: 137-157.

). W Białej ludność napływowa stanowi jeszcze większy odsetek. W 1890 roku za rodowitych bialan uznano 2432 osoby. Miasto w tym czasie zamieszkiwało 5190 osób ludności napływowej (Polak 2010: 381

). W Białej ludność napływowa stanowi jeszcze większy odsetek. W 1890 roku za rodowitych bialan uznano 2432 osoby. Miasto w tym czasie zamieszkiwało 5190 osób ludności napływowej (Polak 2010: 381 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

).

). Wytwórczość tkacka rozwijała się również w Wilamowicach. Dzięki pieniądzom pochodzącym z tej działalności w roku 1808 mieszkańcy tej osady wykupili się z pańszczyzny, a same Wilamowice już w 10 lat później uzyskały prawa miejskie (Wicherkiewicz 2003: 10

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

).

). Po upadku Cesarstwa Austro-Węgierskiego tereny bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej weszły w skład Polski. Obszar położony na wschód od rzeki Białej włączony został do województwa krakowskiego. Nowy porządek nie utrzymał się długo. W 1939 roku nazistowskie Niemcy wywołały II wojnę światową. Gdy ta w 1945 roku dobiegła końca, władzę w Polsce przejęli komuniści, którzy wobec niemieckojęzycznej ludności zastosowały zasadę odpowiedzialności zbiorowej. Zarówno ci, którzy aktywnie wspierali hitleryzm, jak i ci, którzy z tym totalitaryzmem nie mieli nic wspólnego, zmuszeni zostali do opuszczenia miejsca zamieszkania i osiedlenia się w Niemczech lub Austrii.

Masowych wysiedleń uniknęli jedynie mieszkańcy Wilamowic, którym jednak zakazano posługiwania się własnym językiem[4

przyp04 / komentarz/comment /

przyp04 / komentarz/comment / Badacze (dziejów) Wilamowic zastanawiają się, na ile wiążący administracyjnie był zakaz używania języka i noszenia strojów wilamowskich, odczytany wiosną 1945 roku z ambony kościoła w Wilamowicach.

].

].Mitologia pochodzenia

W niemieckojęzycznych publikacjach dotyczących ludności bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej nie ma właściwie informacji, mówiących o tym skąd ona przybyła. Ważniejszy wydaje się być sam fakt kolonizacji nowych terenów. Nieliczne wzmianki na ten temat (Wagner 1935: 193 Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

) trudno jednak uznać za mitologię, niezależnie od sensu, jaki przypisuje się temu słowu. Jeżeli mitologię uznać nie za zbiór fałszywych przekonań, ale za opowieść dotyczącą początków jakiejś społeczności i w pewien sposób ją organizującą, to mianem tym można określić poglądy Wilamowian i hałcnowian dotyczące ich pochodzenia.

) trudno jednak uznać za mitologię, niezależnie od sensu, jaki przypisuje się temu słowu. Jeżeli mitologię uznać nie za zbiór fałszywych przekonań, ale za opowieść dotyczącą początków jakiejś społeczności i w pewien sposób ją organizującą, to mianem tym można określić poglądy Wilamowian i hałcnowian dotyczące ich pochodzenia. Wilamowice

Większość Wilamowian nie uznawała i nie uznaje samych siebie za Niemców. Uważają się raczej za potomków Flamandów, Fryzów, a nawet plemion anglosaskich. Według popularnej w miasteczku opowieści protoplaści Wilamowian wywodzą się znad dolnej Łaby, skąd wypierani przez Duńczyków udali się do Anglii, gdzie uczestniczyli w wielu operacjach militarnych. Przegrana wspieranego przez nich króla Haralda pod Hastings i będąca konsekwencją tej porażki ekspansja Normanów sprawiła jednak, że zmuszeni byli do osiedlenia się w Niderlandach. Wielka powódź, która nawiedziła tamte tereny zmusiła ich jednak do dalszej wędrówki, mającej kres w miejscu, gdzie dziś znajdują się Wilamowice (por. np. Libera i Robotycki 2001 Libera i Robotycki 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Libera i Robotycki 2001 / komentarz/comment / Libera, Zbigniew i Czesław Robotycki 2001. „Wilamowice i okolice w ludowej wyobraźni”, w: Barciak 2001: 371-400.

; Filip 2005: 152

; Filip 2005: 152 Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment / Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.

; Wicherkiewicz 2003: 15-16

; Wicherkiewicz 2003: 15-16 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

).

). Pogląd o nieniemieckim pochodzeniu mieszkańców Wilamowic musiał być rozpowszechniony także poza miasteczkiem. Dowodem na to jest wiersz A Welmeßajer ai Berlin pochodzącego z Białej Jacoba Bukowskiego (1860: 111

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment /

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment / Bukowski, Jacob 1860. Gedichte in der Mundart der deutschen schlesisch-galizischen Gränzbewohner resp. von Bielitz-Biala. Bielitz: Zamarski. [przedruk w: Wagner 1935: 1-190].

) o wesołym wilamowskim kupcu, który przybywa do Berlina, by sprzedawać tkaniny[5

) o wesołym wilamowskim kupcu, który przybywa do Berlina, by sprzedawać tkaniny[5 przyp05 / komentarz/comment /

przyp05 / komentarz/comment / W literaturze (np. Wicherkiewicz 2001) pojawia się przekonanie, że nie jest to wiersz pochodzący z Wilamowic, a jedynie zapisany przez autora. Komentarze do zbioru poezji Bukowskiego (Wagner 1935: 311), sam jego układ, a także „nieludowy” styl wiersza, a przede wszystkim fakt, że nie jest on zapisany w języku wilamowskim, potwierdzają tezę o tym, że sam Bukowski jest jego autorem.

]:

]:| Kom of Berlin a froumer Welmeßajer, Un wou a stond, an wou a ging, Om Reng, ai olla Gossa, olla Stroßa, Do rief a met sem tiefa Baß: ‘Kajf Drellich! faina Welmeßajer Drellich!’ Sou tree har’s fort de ganze Woch‘/ De fremda Loit, se hon an wing verstanda, Ma docht‘ har wär vo England har. -Dos ei kaj Wuinder; denn de Welmeßajer, Die stomma jou vo derta har. – | Wesoły wilamowianin przybywa do Berlina, To przystanął, to pochodził, Po rynku, po wszystkich ulicach i uliczkach. Aż krzyknął swym niskim basem: ‘Kupujcie drelichy! Piękne wilamowskie drelichy!’ Tak przepędził cały tydzień. Obcy ludzie rozumieli go niewiele, Myślano, że przybył z Anglii. Nic w tym dziwnego: przecie wilamowianie. Ci pochodzą wszak stamtąd. |

(tłumaczenie za: Wicherkiewicz 2001: 521 Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2001. „Piśmiennictwo w etnolekcie wilamowskim”, w: Barciak 2001: 520-538.

)

)

Tekst Bukowskiego jest zarazem najstarszym opublikowanym źródłem odnoszącym się do wilamowskiego. Udało się jednak znaleźć i starsze rękopiśmienne źródła ze wzmiankami o Wilamowicach i języku ich mieszkańców (Augustin 1842: 166-167 Augustin 1842 / komentarz/comment /

Augustin 1842 / komentarz/comment /

Augustin, Franz 1842. Jahrbuch oder Zusammenstellung geschichtlicher Thatsachen, welche die Gegend con Oswieczyn und Saybusch angehen. Bearbeitet durch Franz Augustin Pfarrer der Stadt Saybusch 1842 ad A R D Andrea de Pleszowski porocho Bielanensi propria namu descriptum. [ze zbiorów Archiwum Państwowego w Katowicach, Oddział w Żywcu]

).

).

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2001. „Piśmiennictwo w etnolekcie wilamowskim”, w: Barciak 2001: 520-538.

)

)Tekst Bukowskiego jest zarazem najstarszym opublikowanym źródłem odnoszącym się do wilamowskiego. Udało się jednak znaleźć i starsze rękopiśmienne źródła ze wzmiankami o Wilamowicach i języku ich mieszkańców (Augustin 1842: 166-167

Augustin 1842 / komentarz/comment /

Augustin 1842 / komentarz/comment / Augustin, Franz 1842. Jahrbuch oder Zusammenstellung geschichtlicher Thatsachen, welche die Gegend con Oswieczyn und Saybusch angehen. Bearbeitet durch Franz Augustin Pfarrer der Stadt Saybusch 1842 ad A R D Andrea de Pleszowski porocho Bielanensi propria namu descriptum. [ze zbiorów Archiwum Państwowego w Katowicach, Oddział w Żywcu]

).

).W samych Wilamowicach taki obraz własnego pochodzenia utrwalił się pod wpływem publikacji pochodzących z początku XX wieku. Józef Latosiński, autor Monografii Miasteczka Wilamowic, zwanej czasem „wilamowską biblią” (Libera i Robotycki 2001: 377

Libera i Robotycki 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Libera i Robotycki 2001 / komentarz/comment / Libera, Zbigniew i Czesław Robotycki 2001. „Wilamowice i okolice w ludowej wyobraźni”, w: Barciak 2001: 371-400.

) stwierdził na początku swojej książki, że osadnicy, którzy założyli Wilamowice pochodzili z północnych Niemiec. Swoje twierdzenie argumentował w ten sposób:

) stwierdził na początku swojej książki, że osadnicy, którzy założyli Wilamowice pochodzili z północnych Niemiec. Swoje twierdzenie argumentował w ten sposób:Położenie księstwa Schaumburg-Lippe, leżącego dość blizko granicy holenderskiej, oraz Bremy, wskazuje, że pierwsi Wilamowiczanie stamtąd pochodzili, a to po pierwsze ze względu na gwarę miejscową, posiadającą obok rdzennego pierwiastku dolno-niemieckiego także cechy holenderskie i anglosaskie, a po drugie, że w księstwie Schaumburg-Lippe kwitnie dotychczas w wysokim stopniu przemysł tkacki [...] (Latosiński 1909: 14Jednakże w dalszej części książki, powołując się na wiersz opisujący budowę wieży w 1729 roku, twierdzi on, że już w tamtym czasie Wilamowianie nie uważali się za Niemców (Latosiński 1909: 173Latosiński 1909 / komentarz/comment /

Latosiński, Józef 1909. Monografia Miasteczka Wilamowic. Na podstawie źródeł autentycznych. Kraków. [przedruk 1990].).

Latosiński 1909 / komentarz/comment /

Latosiński 1909 / komentarz/comment / Latosiński, Józef 1909. Monografia Miasteczka Wilamowic. Na podstawie źródeł autentycznych. Kraków. [przedruk 1990].

).

).Opinię o (anglo-)saskim pochodzeniu założycieli Wilamowic przedstawił też miedzy innymi Ludwik Młynek (1907

Młynek 1907 / komentarz/comment /

Młynek 1907 / komentarz/comment / Młynek, Ludwik 1907. Narzecze wilamowickie. Tarnów: J. Pisz.

) – pochodzący z Tarnowa nauczyciel i etnograf - autor pierwszego monograficznego opracowania Narzecza wilamowickiego. Pisał on:

) – pochodzący z Tarnowa nauczyciel i etnograf - autor pierwszego monograficznego opracowania Narzecza wilamowickiego. Pisał on: praojcowie Wilamowiczan przybyli „ze Saksonii, stamtąd, gdzie mieszkali dawniej Anglo-Sasi, których też uważają za swoich przodków. Nazwiska rodowe: Foks, Figwer, Danek i t. p. mają być na to jedynym dowodem — jako „zabytki narzecza anglo-saskiego“. Stąd niektórzy uważają Wilamowiczan za Holendrów, którzy z Anglo-Sasami są poniekąd spokrewnieni. Inni wreszcie powiadają, że Wilamowiczanie przybyli ze Śląska pruskiego za czasów Józefa II. Nie brak i takich, co dowodzą, że kolonizacya Wilamowic odbywała się powoli, że w różnych czasach i z różnych stron przybywali niemieccy koloniści i Wilamowice zaludniali stopniowo (1907: 8-10wcześniej zaś:Młynek 1907 / komentarz/comment /

Młynek, Ludwik 1907. Narzecze wilamowickie. Tarnów: J. Pisz.),

Kto dał początek Wilamowicom i skąd pierwsi Wilamowiczanie przybyli, trudno oznaczyć, tembardziej że nie mamy żadnych dokumentów pod ręką, któreby nam pochodzenie Wilamowiczan dokładnie wyświetlić mogły — Wilamowiczanie zaś sami są nadzwyczaj skąpi w udzielaniu potrzebnych ku temu wiadomości — a jest możebne, że ich wcale nie posiadają. (…) Jedni n. p. opowiadali mi, że Wilamowice miał założyć niejaki „Wilhelm“, rodem z Alemanii, który z bratem swoim podczas polowania w te strony się zabłąkał. Okolica, w której się niespodziewanie znalazł, wydała mu się tak uroczą, że nazwał ją swojem „okiem“, „Wilhelms aug“ — a niebawem do niej swoich krajan Alemańczyków przyprowadził i pozwolił im się tam osiąść.Praca Młynka zawiera również interesujący, bo sprzed ponad wieku, obraz wewnątrzjęzykowy wilamowszczyzny, zwłaszcza w warstwie fonetycznej.

Twierdzenie o nieniemieckim pochodzeniu mieszkańców Wilamowic najpełniej wyrażone jest w dziełach Floriana Biesika, najwybitniejszego twórcy literatury w języku wilamowskim. Żyjący w latach 1850-1926, rodzony Wilamowian, po naukach w Krakowie i Wiedniu wstąpił na ścieżkę kariery urzędniczo-kolejowej, której zwieńczeniem stała się objęta posada „nadoficjała Kolei Południowej” w Trieście. To tam „Flora-Flora” (pseudonim literacki, a jednocześnie przydomek rodowy Floriana Biesika z Wilamowic; we współczesnej pisowni: Fliöera-Fliöera) zetknął się z twórczością Dantego Alighieri i jego wpływem na powstanie i upowszechnienie literackiego języka włoskiego, pragnąc stać się takimż Dantem dla pozostawionego na drugim, północnym krańcu Monarchii Austro-Węgierskiej ukochanego i wytęsknionego języka wymysojrysz (w dzisiejszej pisowni wymysiöeryś). Pokaźną część przedmowy do jego najobszerniejszego poematu Óf jer wełt („Na tamtym świecie”, w dzisiejszej pisowni Uf jer wełt - Wicherkiewicz 2003

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

) stanowi opis odysei przodków wilamowian, kontaktów językowych, kulturowych i podróżniczych przodków Wilamowian, oraz próby wyjaśnienia pochodzenia ich (samych i ich) języka, m.in. poprzez wspomnienie kontaktów autora z Fryzami, których zwyczaje i charaktery, okazywały się

być jego zdaniem nadzwyczaj podobne do tych, które znał ze swojej

rodzinnej miejscowości (tłumaczenie tekstu Biesika z 1924 roku, w: Wicherkiewicz 2003: 41-48

) stanowi opis odysei przodków wilamowian, kontaktów językowych, kulturowych i podróżniczych przodków Wilamowian, oraz próby wyjaśnienia pochodzenia ich (samych i ich) języka, m.in. poprzez wspomnienie kontaktów autora z Fryzami, których zwyczaje i charaktery, okazywały się

być jego zdaniem nadzwyczaj podobne do tych, które znał ze swojej

rodzinnej miejscowości (tłumaczenie tekstu Biesika z 1924 roku, w: Wicherkiewicz 2003: 41-48 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

). Pisze on:

). Pisze on: Z tym więc językiem zawojowali Anglię. z nim wrócili na stały ląd do fryzyi i do Wilamowic. Język ten jest więc jako najstarszy ojcem innych dziś żywych języków germańskich, jak angielskiego, hollandzkiego, niemieckiego, szwedzkiego i lubo pośredniczył między nimi, został on sam dla siebie.W innym swoim poemacie Wymysau an wymysojer („Wilamowice i Wilamowianie”; Wicherkiewicz 2003: 22

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

, Anders 1933: 12

, Anders 1933: 12 Anders 1933 / komentarz/comment /

Anders 1933 / komentarz/comment / Anders, Heinrich 1933. Gedichte von Florian Biesik in der Mundart von Wilamowice. Kraków: nakładem Uniwersytetu Poznańskiego.

), pisze Biesik o przodkach:

), pisze Biesik o przodkach: Vertryjn wegia religionNapisany zaś w marcu 1922 roku poemacik S’Wymysojerysze („Wilamowszczyzna”) poświęcony jest w całości rodzimemu etnolektowi (Wicherkiewicz 2003: 352-353

polityk an rebellion

wandytas fy England, Holland

an kooma bocy óf Półłand.

Wygnani z powodu religii

polityki i rebelii

wywędrowali z Anglii, Holandii

i przybyli aż do Polski.

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

; Anders 31-34

; Anders 31-34 Anders 1933 / komentarz/comment /

Anders 1933 / komentarz/comment / Anders, Heinrich 1933. Gedichte von Florian Biesik in der Mundart von Wilamowice. Kraków: nakładem Uniwersytetu Poznańskiego.

).

).Poglądów i dowodów Floriana Biesika (w znacznej mierze sięgających do konstruowanej etnomitologii i językoznawstwa ludowego) nie podzielał jego brat Hermann Mojmir – współautor 2 tomów Słownika niemieckiego dialektu Wilamowic” (Mojmir 1930-1936

Mojmir 1930-1936 / komentarz/comment /

Mojmir 1930-1936 / komentarz/comment / Mojmir, Hermann 1930-1936. Wörterbuch der deutschen Mundart von Wilamowice. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

) pod współred. (1) A. Kleczkowskiego i (2) H. Andersa. Zapewne dzięki naukowym kontaktom z tymi germanistami Mojmir uważał wilamowski za typowy śląski dialekt niemieckiego, zrównując go zwłaszcza z szynwałdzkim (dialekt Schönwaldu k/ Gliwic – Gusinde 1911

) pod współred. (1) A. Kleczkowskiego i (2) H. Andersa. Zapewne dzięki naukowym kontaktom z tymi germanistami Mojmir uważał wilamowski za typowy śląski dialekt niemieckiego, zrównując go zwłaszcza z szynwałdzkim (dialekt Schönwaldu k/ Gliwic – Gusinde 1911 Gusinde 1911 / komentarz/comment /

Gusinde 1911 / komentarz/comment / Gusinde, Konrad 1911. Eine vergessene Sprachinsel im polnischen Oberschlesien (die Mundart von Schönwald bei Gleiwitz). Breslau: Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. [przedruk: 2012]

). Już prawie dekadę wcześniej profesor germanistyki Adam Kleczkowski wydał najbardziej do tej pory kompletne monografie lingwistyczne dotyczące niemieckiego dialektu Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji - jak go nazywał i opisywał – przedstawiające monograficznie wilamowską fonetykę, morfologię i składnię (Kleczkowski 1920

). Już prawie dekadę wcześniej profesor germanistyki Adam Kleczkowski wydał najbardziej do tej pory kompletne monografie lingwistyczne dotyczące niemieckiego dialektu Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji - jak go nazywał i opisywał – przedstawiające monograficznie wilamowską fonetykę, morfologię i składnię (Kleczkowski 1920 Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1920 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1920. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Fonetyka i fleksja. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności.

, 1921

, 1921 Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1921 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1921. Dialekt Wilamowic w zachodniej Galicji. Składnia (szyk wyrazów). Poznań.

). Wraz z leksykonem Mojmira dzieła te stanowią kanon opisu wilamowszczyzny w jej okresie rozkwitu, rozwoju i pełnego funkcjonowania.

). Wraz z leksykonem Mojmira dzieła te stanowią kanon opisu wilamowszczyzny w jej okresie rozkwitu, rozwoju i pełnego funkcjonowania.Przekonanie o niderlandzkich korzeniach Wilamowic utrzymuje się do dzisiaj zarówno wśród mieszkańców okolicznych miejscowości, jak i samych Wilamowian. Duży ośrodek agroturystyczny, który powstał tu kilka lat temu, nazwano „Flamandia”.

Kod ISO

ISO 639-3 wym

- Rozalia Hanusz - opowieść o Wilamowicach

- biogram Heleny Biba - część 1

- biogram Heleny Biba - część 2

- AKowalczyk i TKról

- H. Biba w ogrodzie 1

- H. Biba w ogrodzie 2

- J. Gara - powitanie

- J. Gara o okolicy w Wilamowicach

- J. Gara i jego twórczość (A)

- J. Gara i jego twórczość (B)

- J. Gara o swoim życiu

- J. Gara o innych gwarach

- J. Gara o Żydach wilamowskich

- Pierzowiec 1

- Pierzowiec 2

- A.Foks i H. Biba - strój wilamowski 2

- J. Gara o Hałcnowie

- Florian Biesik - poemat "Óf jer wełt"

- A.Foks i H. Biba - strój wilamowski 1

- artykuł o języku wilamowskim "Rzeczpospolita" cz.1

- próba zespołu Wilamowice - Diöt fum hejwuł...

- próba zespołu Wilamowice

- FotoRzepa - film o Wilamowicach

- Wilamowice w Sejmie część 2

- film flamandzkiej TV o Wilamowicach z 1977 r.

- E. Matysiak śpiewa "Pater s'foter..."

- Wilamowice w Sejmie część 1

- Wilamowice w Sejmie część 3

- H.Rozner opowiada o rodzinie na fotografii

- H. Nowak śpiewa "Wymysiöejer śejny måkja"

- Kontakty językowe wilamowsko-polskie

- Wurbs 1981

- Filip 2005

- Wicherkiewicz 2001

- Wicherkiewicz 2003

- Bock 1916a

- Barciak 2001

- Wagner 1935

- Libera i Robotycki 2001

- Bukowski 1860

- Latosiński 1909

- Kleczkowski 1920

- Kleczkowski 1921

- Mojmir 1930-1936

- Lasatowicz 1992

- Ritchie 2012

- Wackwitz 1932

- Trambacz 1971

- Księżyk 2008

- Weinreich 1958

- Wicherkiewicz i Zieniukowa 2001

- Neels 2012

- Gara 2004

- Morciniec 1995

- Andrason 2010

- Andrason 2011

- Kleczkowski 1915

- Młynek 1907

- Król 2011

- Augustin 1842

- Anders 1933

- Ryckeboer 1984

- Morciniec 1984

- Besch et al 1983

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- Jungandreas 1933

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- opowieść o dawnych Wilamowicach

- autor T.Król czyta fragmenty "s'Ława fum Wilhelm"

- Anna Kowalczyk czyta fragment s'Ława fum Wilhelm

- Józef Gara - fragment "Óf jer wełt" F. Biesika

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Dy Wajnaochta"

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Ym Wynter"

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Z Śwojmła kom cyryk"

- J.Gara czyta swój utwór "Paoter s'Faoter"

- J.Gara śpiewa swój utwór "Śłöf maj Kyndła"

- J.Gara śpiewa swój utwór "Śtyły Naocht"

- J.Gara śpiewa swój utwór "Jyr kyndyn kumt oły"

- polskojęzyczny wstęp w rękopisie Floriana Biesika

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- strona tytułowa manuskryptu F. Biesika

- Mapa Wilamowic (duży rozmiar)

- Mapa Wilamowic (mały rozmiar)

- fotografia z wesela w Wilamowicach

- fotografia śmierguśników w Wilamowicach

- Pamiętniki Jana Danka 'Płaćnika' z 1923 r.

- fragment Pamiętników Jana Danka po wilamowsku

- fotografia weselnych śmierguśników w Wilamowicach

- poemat T. Króla - "s'Ława fum Wilhelm"

- siedziba Stowarzyszenia "Wilamowianie"

- Stowarzyszenie "Wilamowianie"

- reklama po wilamowsku 1

- reklama po wilamowsku 2

- spotkanie Stowarzyszenia

- manuskrypt z przydomkami domostw w Wilamowicach

- strona tytułowa rękopisu J.Rosnera z przydomkami

- strona tytułowa rękopisu Pamiętników J.Danka

- rękopis wierszyka "Ys wa amół ym wynter kałt"

- maszynopis piosenki "Fo ynsyn raichia faldyn"

- rękopis kołysanki "Kyndła maj, śłöf śun aj!"

- L. Młynek "Narzecze wilamowickie"- strona tytułowa

- program konferencji nt.języków zagrożonych, Sejm

- konferencja międzynarodowa w Wilamowicach, 2014 r.

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 1

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 2

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 3

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 4

- Wilamowice w Sejmie i kard. K.Nycz

- kard. K. Nycz w Sejmie

- Wilamowianie w Sejmie 5

- fotografia 3 dziewcząt i mężczyzny z Wilamowic

- fotografia wesela w Wilamowicach 1

- fotografia wesela w Wilamowicach 2

- kartka pocztowa po wilamowsku

- tablice "Kolorowa żałoba w Wilamowicach" T.Króla

- A.Kleczkowski Dialekt Wilamowic-fonetyka i fleksja

- A.Kleczkowski Dialekt Wilamowic-składnia

- H.Mojmir-"Woerterbuch der Mundart von Wilamowice"

- H.Anders - "Gedichte von Florian Biesik"

- T. Wicherkiewicz - "The Making of a Language"

- nagrobek K. i J.Foksów - Wilamowice

- nagrobek T. i J.Foksów - Wilamowice

- nagrobej F. i K. Zejmów

- nagrobek F. i A. Moslerów - Wilamowice

- grób A. Rosner Korczyk - Wilamowice

- fragment nt.Wilamowic w rękopisie F.Augustina

- strona tytułowa Bukowski 1860

- fotografia stroju żałobnego w Wilamowicach 1

- fotografia stroju żałobnego w Wilamowicach 2

- Samogłoski języka wilamowskiego

- Wymysorys monophtong vowels