rusińsko-łemkowski

Nazwa

Endolingwonimy:

Łemkowie swój język nazywają лемкiвскiй язык (Fontański i Chomiak 2000 Fontański i Chomiak 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Fontański i Chomiak 2000 / komentarz/comment/r / Fontański, Henryk & Mirosława Chomiak 2000. Gramatyka języka łemkowskiego. Katowice: Śląsk.

).

).Egzolingwonimy:

- w języku polskim: język łemkowski, język Łemków lub mowa Łemków ( Rieger 1995: 9

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper. );

); - w języku angielskim: Lemko (http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=rue);

- w języku ukraińskim często лемківські говірки – w liczbie mnogiej (Łesiw 1997: 9

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Українскі говірки у Польщі. Warszawa: Archiwum Ukraińskie. );

); - w języku rosyjskim niegdyś рѣчь лемкив (Połowinkin 1896: 521

Połowinkin 1896 / komentarz/comment/r /

Połowinkin 1896 / komentarz/comment/r /

Половинкинъ, Ир. П. [Połowinkin] 1896. „Лемки”, w: К. К. Арсеньев и Ф. Ф. Петрушевский (red.) Энциклопедическiй словарь XVIIА. С. Петербург: Типо-Литографiя И.А. Ефрона. ), dziś – лемковский язык.

), dziś – лемковский язык.

Endoetnonimy:

Podobnie jak pozostałe grupy rusińskie [1 przyp01 / komentarz/comment /

przyp01 / komentarz/comment / Termin Rusin używany był początkowo jako określenie Słowian wschodnich zamieszkujących teren prowincji austriackich (Austro-Węgier), Galicji i Bukowiny. Na początku XX w., po wykształceniu się świadomości narodowej Ukraińców, termin ten wraz z jego wariantem Rusnak stosowany był do ludności wschodniosłowiańskiej, która nie postrzegała się jako część narodu ukraińskiego. Obecnie za ludność rusińską uważa się Łemków w Polsce oraz Karapatorusinów zamieszkujących tereny w Słowacji (kraj preszowski - słow. Prešovský kraj / rusiń. Пряшівскый край), Ukrainy (obwód zakarpacki), Rumunii (okręg Marmarosz – rum. Maramureș / ukr. Мармарош), Węgier (enklawy na północy kraju) oraz byłej Jugosławii (Srem - serb. ukr. i rusiń. Срем i Wojwodina - serb. Војводина / ukr. i rusiń. Войводина) (#Magocsi 2004: 15-17).

], w przeszłości grupa do samookreślenia używała nazw Руснаки, Русини, czy люди руськой вiры [2

], w przeszłości grupa do samookreślenia używała nazw Руснаки, Русини, czy люди руськой вiры [2 przyp02 / komentarz/comment /

przyp02 / komentarz/comment / Określenie „ludzie wiary ruskiej” stanowiło odniesienie do przynależności grupy do cerkwi prawosławnej, a później unickiej, co było wyznacznikiem odrębności w stosunku do sąsiedniej katolickiej ludności polskiej i słowackiej.

] (Magocsi 2004: 18

] (Magocsi 2004: 18 Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). W XX w. przyjęła się nazwa Лемко, która powstała na pograniczu łemkowsko-bojkowskim [3

). W XX w. przyjęła się nazwa Лемко, która powstała na pograniczu łemkowsko-bojkowskim [3 przyp03 / komentarz/comment /

przyp03 / komentarz/comment / Bojkowie – grupa etniczna zamieszkująca Karpaty Wschodnie na wschód od terenów zamieszkanych przez Łemków: od Wysokiego Działu w Bieszczadach na zachodzie, do doliny Łomnicy (ukr. Лімниця) w Gorganach (Ґорґани) na wschodzie.

] od występującego w języku Łemków słowa лем 'tylko' i stanowiła z początku przezwisko (Werchratski 1902: 1

] od występującego w języku Łemków słowa лем 'tylko' i stanowiła z początku przezwisko (Werchratski 1902: 1 Werchratski 1902 / komentarz/comment/r /

Werchratski 1902 / komentarz/comment/r / Верхратський, Іван [Werchratski] 1902. Про говор галицких лемків. Lwów: Наукове товариство імені Шевченка.

). Po raz pierwszy sformułowanie Лімки pojawia się w literaturze naukowej u Lewickiego (1834: V

). Po raz pierwszy sformułowanie Лімки pojawia się w literaturze naukowej u Lewickiego (1834: V Lewicki 1834 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewicki 1834 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewicki, Joseph 1834. Grammatik der ruthenischen oder kleinrussischen Sprache in Galizien. Przemyśl: Griech. Kath. Bischöflichen Buchdruckerey.

).

). Egzoetnonimy:

- w języku polskim do teraz jeszcze spotyka się określenie Rusini, choć częściej spotykana nazwa to Łemkowie (Rieger 1995: 9

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper. ). W przeszłości znane były także określenia Czuchońcy oraz Kurtaki, pochodzące od czuhy – charakterystycznego płaszcza, będącego elementem stroju Łemków (http://www.krynica.pl/Nazwa-%C5%81emko-c165.html);

). W przeszłości znane były także określenia Czuchońcy oraz Kurtaki, pochodzące od czuhy – charakterystycznego płaszcza, będącego elementem stroju Łemków (http://www.krynica.pl/Nazwa-%C5%81emko-c165.html); - w języku angielskim najczęściej spotykana nazwa grupy to Lemkos (Duć-Fajfer: http://www.rusyn.org/ethlemkos.html);

- w języku rosyjskim poza nazwą лемки, znane były także określenia полпщуки, куртаки, чугонци (Połowinkin 1896: 521

Połowinkin 1896 / komentarz/comment/r /

Połowinkin 1896 / komentarz/comment/r /

Половинкинъ, Ир. П. [Połowinkin] 1896. „Лемки”, w: К. К. Арсеньев и Ф. Ф. Петрушевский (red.) Энциклопедическiй словарь XVIIА. С. Петербург: Типо-Литографiя И.А. Ефрона. );

); - w języku ukraińskim używane jest określenie лемки, w literaturze spotkać można także лемчаки (Werchratski 1902: 1

Werchratski 1902 / komentarz/comment/r /

Werchratski 1902 / komentarz/comment/r /

Верхратський, Іван [Werchratski] 1902. Про говор галицких лемків. Lwów: Наукове товариство імені Шевченка. ), куртаки, чугaнцi.

), куртаки, чугaнцi.

Historia i geopolityka

Lokalizacja i zasięg

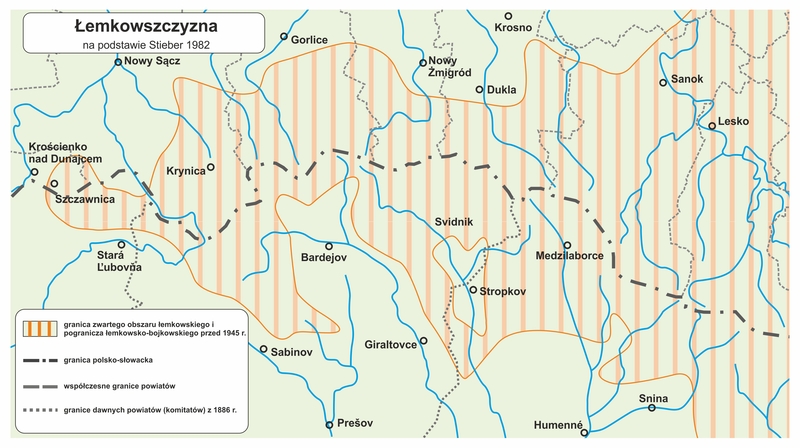

Do 1947 r. Łemkowszczyzna (łemk. Лемковина) obejmowała obszar o kształcie równoleżnikowego klina, o długości około 150 km i szerokości przy podstawie około 60 km, znajdujący się pomiędzy obszarem osadnictwa polskiego na północy i słowackiego na południu.

Mapa Łemkowszczyzny (red.mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz, na podstawie: Stieber 1982

Stieber 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Stieber 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Stieber, Zdzisław 1982. Dialekt Łemków: Fonetyka i Fonologia. Wrocław: Polska Akademia Nauk.

).

).Wschodnią granicę Łemkowszczyzny wyznaczały zlewiska rzek Osławy (w Polsce) oraz Laborca (w Słowacji). Zachodnią granicę Łemkowszczyzny wyznaczało położenie wsi Osturňa (łemk. Остурня) na Zamagurzu (w Słowacji) oraz Biała Woda (Біла Вода), Czarna Woda (Чорна Вода), Jaworki (Явіркы) i Szlachtowa (Шляхтова) na terenie Rusi Szlachtowskiej (Шляхтовська Русь, w Polsce).

Wieś Osturňa, fot. T. Wicherkiewicz.

Mapka Rusi Szlachtowskiej (http://www.jaworki.skpb.lodz.pl/okol_rus.html).

Dość jednoznacznie granicę między ludnością polską i rusińską opisał już D. Zubrzycki (1837: 19-20

Zubrzycki 1837 / komentarz/comment/r /

Zubrzycki 1837 / komentarz/comment/r / Zubrzycki, Dyonizy 1837. Rys do historyi narodu ruskiego w Galicyi i hierarchji cerkiewney w temże krolestwie: Od zaprowadzenia Chrześciaństwa na Rusi aż do opanowania Rusi czerwoney przez Kazimierza Wielkiego od roku 988 do roku 1340 I. Lwów.

):

): Przeszedłszy strumień Wisłok za granice niegdyś między Polską i czerwoną Rusią przyjęty, i zwróciwszy się ku zachodowi, na przestrzeni mniey więcey 50 mil kwa. zaymuiącey, po pod granicę węgierską w górach karpackich w długiey, lecz w miarę iak góry się zwężaią lub rozszerzaią wąskiej linij, w cyrkułach sanockim, iasielskim i sandeckim, mieszka lud plemienia ruskiego obrządek gr. katolickij wyznaiący, w 170 wsiach, z ludnością przeszło 83000 dusz, posiadaiąc dotych czas ieszcze 129 cerkwi. – Linia ta ciągnie się nie tylko do rzeki Poprad, lecz ieszcze i za nią w pobliskości Dunayaca po prawey stronie tegoż, w nayodleglejszym zakątku, obok źródeł uzdrawiaiących szczawnickich, znayduią się ruskie wsie, Szlachtowa, Jaworki, Czarnawoda i (…) Biała woda – Czytelnik zwracający baczność na ten przedmiot, niech sobie oznaczy na mappie Galicyi Lesganika, następuiące ostatnie przez Rusinów zamieszkałe wsie ku północy, w równinach, to iest na podgórzu za Wisłokiem leżące iako to: Wróblik królewski, szlachecki, Ładzin, daley ku Dukli idąc Wułke, Zawadke, Trzciane nad strumieniem Jasiel, Chyrowe, Myscowe, Konty nad Wisłoką, Skalnik, Brzezowe, Pielgrzymke, Kłopotnice, Folusz, Wole Cieklińską, Bednarke, Menciny, Rychwald, Bielanke, Łosie, Klimkowke, Laskowe, Florynke, Binczarowe, Królową ruske, Begusze, Macieiowe, Baranowice, Wierzchomle, i Zubrzyk nad Popradem, a będzie miał granice Rusi zawisłockiey, od plemienia polskiego w równinach osiadłego ią oddzielaiącą. – Wszystkie zatem po lewey ręce tey linij ku granicy węgierskiey leżące włości, są przez Rusinów osiadłe, którży od Rusinów s tey strony Wisłoka w eparohij przemyskiey w górach mieszkających, niczem się bynaymniey nie różnią, a ostatnia ruska wieś ku północy, to jest tak zwana „Królowa Ruska”, o mile zaledwie od Sącza, a o 13 mil od Krakowa jest odległa.

Południowy zasięg ludności łemkowskiej obejmuje: „Niskie Beskidy, Lubowniańską Werchowinę w okolicy Starej Lubowni, Szaryską Werchowinę wzdłuż zachodniego brzegu rzeki Torysy i częściowo Spiską Magurę na południe od Pienin” (Czajkowski 1999: 5

Czajkowski 1999 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czajkowski 1999 / komentarz/comment/r / Czajkowski, Jerzy 1999. Studia nad Łemkowszczyzną. Sanok: Muzeum Budownictwa Ludowego.

).

Warto zwrócić również uwagę, że granice Łemkowszczyzny wyznaczone przez językoznawców nie pokrywały się do końca z obszarami, które zamieszkiwała ludność nazywana przez sąsiadów Łemkami. Podstawą dla używania nazwy Łemko przez lokalną ludność był sam fakt występowania zwrotu łem w gwarze używanej przez mieszkańców danej wsi. Tymczasem obszar występowania tego zwrotu nie pokrywał się z pozostałymi wyznacznikami charakterystycznymi dla grupy etnolingwistycznej określonej jako Łemkowie, jak na przykład stały, polski akcent na przedostatniej sylabie (Stieber 1982: 6-7

).

Warto zwrócić również uwagę, że granice Łemkowszczyzny wyznaczone przez językoznawców nie pokrywały się do końca z obszarami, które zamieszkiwała ludność nazywana przez sąsiadów Łemkami. Podstawą dla używania nazwy Łemko przez lokalną ludność był sam fakt występowania zwrotu łem w gwarze używanej przez mieszkańców danej wsi. Tymczasem obszar występowania tego zwrotu nie pokrywał się z pozostałymi wyznacznikami charakterystycznymi dla grupy etnolingwistycznej określonej jako Łemkowie, jak na przykład stały, polski akcent na przedostatniej sylabie (Stieber 1982: 6-7 Stieber 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Stieber 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Stieber, Zdzisław 1982. Dialekt Łemków: Fonetyka i Fonologia. Wrocław: Polska Akademia Nauk.

).

Fakt, że granica przebiegająca pomiędzy osadnictwem polskim a ruskim na przestrzeni wieków nie ulegała znaczącym zmianom, oznacza również, że linia podziału pomiędzy tymi dwoma grupami była ostra i stabilna (Reinfuss 1961: 63

).

Fakt, że granica przebiegająca pomiędzy osadnictwem polskim a ruskim na przestrzeni wieków nie ulegała znaczącym zmianom, oznacza również, że linia podziału pomiędzy tymi dwoma grupami była ostra i stabilna (Reinfuss 1961: 63 Reinfuss 1961 / komentarz/comment/r /

Reinfuss 1961 / komentarz/comment/r / Reinfuss, Roman 1961. „Stan i problematyka badań nad kulturą ludową Łemkowszczyzny”, w: Witold Dynowski (red.) Etnografia Polska V. Wrocław: Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN, Instytut Historii Kultury Materialnej PAN, s. 63-70.

; Duć-Fajfer 2001: 7-8

; Duć-Fajfer 2001: 7-8 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

). Inaczej przedstawiała się natomiast sytuacja na granicy południowej, gdzie zasięg występowania języka rusińskiego nie pokrywał się z zasięgiem „wiary ruskiej” (Reinfuss 1961: 63

). Inaczej przedstawiała się natomiast sytuacja na granicy południowej, gdzie zasięg występowania języka rusińskiego nie pokrywał się z zasięgiem „wiary ruskiej” (Reinfuss 1961: 63 Reinfuss 1961 / komentarz/comment/r /

Reinfuss 1961 / komentarz/comment/r / Reinfuss, Roman 1961. „Stan i problematyka badań nad kulturą ludową Łemkowszczyzny”, w: Witold Dynowski (red.) Etnografia Polska V. Wrocław: Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN, Instytut Historii Kultury Materialnej PAN, s. 63-70.

; Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8

; Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

Obszar Łemkowszczyzny zamieszkany był przez rdzenną ludność do 1947 r. Tuż po zakończeniu II wojny światowej nastąpiło masowe przesiedlenie Łemków na teren Ukraińskiej Socjalistycznej Republiki Radzieckiej, a następnie, w ramach Akcji „Wisła”, na pozostałe tereny polskie, w szczególności na teren Dolnego Śląska (Stegherr http://wwwg.uni-klu.ac.at/eeo/Rusinisch.pdf: 406; http://oboz.w.of.pl/ofiary.html). Od tego momentu Łemkowie żyją w rozproszeniu, a na miejsca pochodzenia zdołała powrócić jedynie niewielka część grupy.

W okresie przed 1947 r. liczba Łemków na terenie polskiej Łemkowszczyzny wynosiła około 150 000 osób. Zgodnie z informacjami zawartymi w zestawieniu Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z 1938 r. obszar ten zamieszkiwało łącznie 130 121 osób wyznania grekokatolickiego i prawosławnego (GUS RP 1938: 32-45

).

Obszar Łemkowszczyzny zamieszkany był przez rdzenną ludność do 1947 r. Tuż po zakończeniu II wojny światowej nastąpiło masowe przesiedlenie Łemków na teren Ukraińskiej Socjalistycznej Republiki Radzieckiej, a następnie, w ramach Akcji „Wisła”, na pozostałe tereny polskie, w szczególności na teren Dolnego Śląska (Stegherr http://wwwg.uni-klu.ac.at/eeo/Rusinisch.pdf: 406; http://oboz.w.of.pl/ofiary.html). Od tego momentu Łemkowie żyją w rozproszeniu, a na miejsca pochodzenia zdołała powrócić jedynie niewielka część grupy.

W okresie przed 1947 r. liczba Łemków na terenie polskiej Łemkowszczyzny wynosiła około 150 000 osób. Zgodnie z informacjami zawartymi w zestawieniu Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z 1938 r. obszar ten zamieszkiwało łącznie 130 121 osób wyznania grekokatolickiego i prawosławnego (GUS RP 1938: 32-45 GUS RP 1938 / komentarz/comment/r /

GUS RP 1938 / komentarz/comment/r / Statystyka Polski, z. 68/1938. Warszawa: GUS RP.

; GUS RP 1938a: 26-35

; GUS RP 1938a: 26-35 GUS RP 1938a / komentarz/comment/r /

GUS RP 1938a / komentarz/comment/r / Statystyka Polski, z. 88/1938a. Warszawa: GUS RP.

). Tamtejsi Łemkowie zasiedlali przede wszystkim tereny wiejskie, natomiast większe ośrodki miejskie położone na obszarze Łemkowszczyzny miały zdecydowanie polski charakter etniczny (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8

). Tamtejsi Łemkowie zasiedlali przede wszystkim tereny wiejskie, natomiast większe ośrodki miejskie położone na obszarze Łemkowszczyzny miały zdecydowanie polski charakter etniczny (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

Na początku XXI w. szacunki dotyczące liczby Łemków można uznać za mocno zróżnicowane. Magocsi (2004: 16

).

Na początku XXI w. szacunki dotyczące liczby Łemków można uznać za mocno zróżnicowane. Magocsi (2004: 16 Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

) pisze o około 90 000 Łemków na terenie Ukrainy oraz 60 000 Rusinów (z których większość stanowią Łemkowie) na terenie Polski, przy czym, jak to często ma miejsce w przypadku mniejszości pozbawionych własnej organizacji państwowej, nie wszyscy przyznają się chętnie do swojej narodowości. Oficjalne dane zebrane podczas Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań w 2002 r. podają liczbę 5863 osób deklarujących narodowość łemkowską oraz 5627 osób używających języka łemkowskiego w kontaktach domowych (http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/nsp2002_tabl9.xls), w tym dla 1444 osób był to jedyny język używany w kontaktach domowych (http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/nsp2002_tabl7.xls). Zgodnie z danymi zebranymi podczas Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań w 2011 r. na terenie Polski mieszka około 10 000 osób uważających się za Łemków (Wyniki Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2011: 18

) pisze o około 90 000 Łemków na terenie Ukrainy oraz 60 000 Rusinów (z których większość stanowią Łemkowie) na terenie Polski, przy czym, jak to często ma miejsce w przypadku mniejszości pozbawionych własnej organizacji państwowej, nie wszyscy przyznają się chętnie do swojej narodowości. Oficjalne dane zebrane podczas Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań w 2002 r. podają liczbę 5863 osób deklarujących narodowość łemkowską oraz 5627 osób używających języka łemkowskiego w kontaktach domowych (http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/nsp2002_tabl9.xls), w tym dla 1444 osób był to jedyny język używany w kontaktach domowych (http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/nsp2002_tabl7.xls). Zgodnie z danymi zebranymi podczas Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań w 2011 r. na terenie Polski mieszka około 10 000 osób uważających się za Łemków (Wyniki Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2011: 18 Narodowy Spis Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Narodowy Spis Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Wyniki Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2011. Podstawowe informacje o sytuacji demograficzno-społecznej ludności Polski oraz zasobach mieszkaniowych. Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

). Zgodnie z tezą Paula Magocsiego, również niektórzy przedstawiciele polskiej administracji krajowej przyznają, że rzeczywista liczba osób, które uważają się za Łemków, jest przynajmniej dwa razy wyższa (http://komentatoreuropa.pl/page107.html).

). Zgodnie z tezą Paula Magocsiego, również niektórzy przedstawiciele polskiej administracji krajowej przyznają, że rzeczywista liczba osób, które uważają się za Łemków, jest przynajmniej dwa razy wyższa (http://komentatoreuropa.pl/page107.html).Historia i geneza

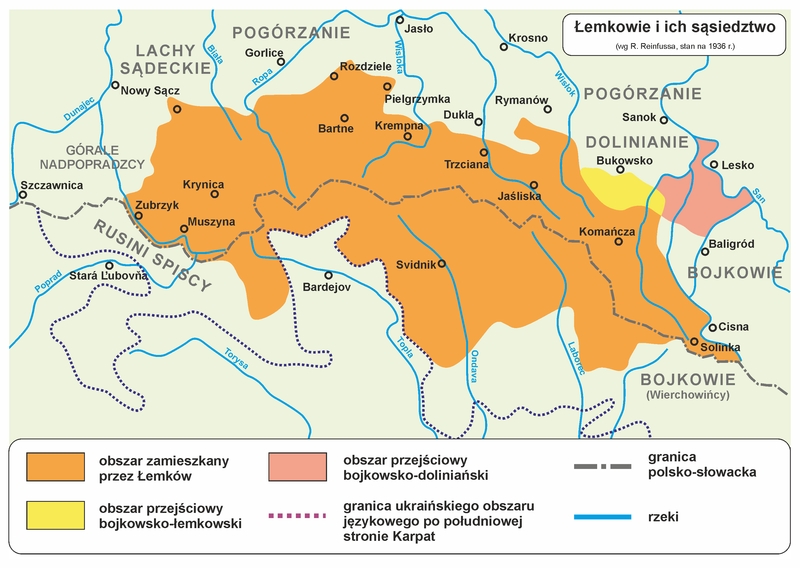

Łemkowie stanowią część makrogrupy etnicznej – Rusinów karpackich – do której zaliczyć można jeszcze Krajniaków [4 przyp04 / komentarz/comment /

przyp04 / komentarz/comment / Krajniacy - grupa etniczna zamieszkująca wioski wokół Pienin Spiskich i Magury Spiskiej.

] (znanych także pod nazwą Rusnaków lub Spiszaków), Dolinian [5

] (znanych także pod nazwą Rusnaków lub Spiszaków), Dolinian [5 przyp05 / komentarz/comment /

przyp05 / komentarz/comment / Dolinianie – grupa etniczna zamieszkująca niegdyś obszar wokół Sanoka, okolice Mrzygłodu oraz tereny na północ i wschód od Leska.

], Bojków (Rusnaków lub Wierchowińców) i Hucułów [6

], Bojków (Rusnaków lub Wierchowińców) i Hucułów [6 przyp06 / komentarz/comment /

przyp06 / komentarz/comment / Huculi – grupa etniczna zamieszkująca ukraińską i rumuńską część Karpat Wschodnich, na wschód od terenów zamieszkanych przez Bojków (patrz przypis 3).

] (Magocsi 2004: 18

] (Magocsi 2004: 18 Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

).

).

Mapa obszarów zamieszkanych przez Łemków oraz sąsiadujące z nimi grupy etniczne (red.mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz, na podstawie: Reinfuss 1990: 14

Reinfuss 1990 / komentarz/comment/r /

Reinfuss 1990 / komentarz/comment/r / Reinfuss, Roman 1990. Śladami Łemków. Warszawa: PTTK „Kraj”.

).

).Istnieją dwie przeciwstawne teorie wyjaśniające pochodzenie Łemków oraz sposób, w jaki znaleźli się oni na terenie Łemkowszczyzny: teoria autochtonizmu oraz teoria migracyjna. Zgodnie z teorią autochtoniczną, Łemkowie są bezpośrednimi potomkami plemienia Białych Chorwatów, o których pisał cesarz bizantyński Konstantyn VII Porfirogeneta oraz którzy wspomnieni zostali w spisanej w XII w. na terenie Rusi Kijowskiej kronice Powieść minionych lat. Biali Chorwaci mieli zamieszkiwać tereny doliny Dunaju już około VI w. i tworzyć podległą Węgrom tzw. Marchię Rusinów (Marchia Ruthenorum - Magocsi 2004: 23

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). Według innej wersji tej teorii Rusini wchodzić mieli w skład Rusi Kijowskiej, a po jej upadku, w związku z naporem ludności polskiej, wycofali się na tereny trudno dostępne (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8

). Według innej wersji tej teorii Rusini wchodzić mieli w skład Rusi Kijowskiej, a po jej upadku, w związku z naporem ludności polskiej, wycofali się na tereny trudno dostępne (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

).

Mapa – tereny zamieszkane przez plemię Białych Chorwatów zgodnie z teorią migracyjną (red.mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz, na podstawie: Rybakow 1983

Rybakow 1983 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rybakow 1983 / komentarz/comment/r / Rybakow, Borys 1983. Pierwsze wieki historii Rusi. Warszawa: PIW.

).

).Zgodnie z teorią migracyjną (Reinfuss 1961: 63

Reinfuss 1961 / komentarz/comment/r /

Reinfuss 1961 / komentarz/comment/r / Reinfuss, Roman 1961. „Stan i problematyka badań nad kulturą ludową Łemkowszczyzny”, w: Witold Dynowski (red.) Etnografia Polska V. Wrocław: Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN, Instytut Historii Kultury Materialnej PAN, s. 63-70.

) Łemkowie wywodzą się od ludności, która na tereny dziś przez nich zamieszkałe dotarła w XV w. w wyniku migracji Wołochów - wędrownych pasterzy, pochodzących z terenów Półwyspu Bałkańskiego. Brak jest znanych źródeł historycznych, które umożliwiłyby jednoznaczne określenie pochodzenia Łemków (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8

) Łemkowie wywodzą się od ludności, która na tereny dziś przez nich zamieszkałe dotarła w XV w. w wyniku migracji Wołochów - wędrownych pasterzy, pochodzących z terenów Półwyspu Bałkańskiego. Brak jest znanych źródeł historycznych, które umożliwiłyby jednoznaczne określenie pochodzenia Łemków (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 8 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

). Jak pisze Magocsi (2004: 26

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

), Łemkowie trafili pod panowanie polskie w połowie XIV w. Trwało ono do 1772 r., kiedy to Łemkowszczyzna znalazła się pod rządami austriackimi. Wcześniej, w XVI w. utracili oni początkowe przywileje społeczne oraz ekonomiczne i zostali w prawach sprowadzeni do roli chłopstwa, włącznie z przywiązaniem do ziemi (Magocsi 2004: 26-27

), Łemkowie trafili pod panowanie polskie w połowie XIV w. Trwało ono do 1772 r., kiedy to Łemkowszczyzna znalazła się pod rządami austriackimi. Wcześniej, w XVI w. utracili oni początkowe przywileje społeczne oraz ekonomiczne i zostali w prawach sprowadzeni do roli chłopstwa, włącznie z przywiązaniem do ziemi (Magocsi 2004: 26-27 Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). Przez cały ten czas jednym z głównych czynników, który umożliwił im zachowanie poczucia odrębności, było wyznanie prawosławne. Wydarzeniem, które miało w znacznym stopniu wpłynąć na historię Łemków, było zatem zawarcie unii brzeskiej w 1596 r., zgodnie z postanowieniami której część duchowych prawosławnych w Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów uznała zwierzchnictwo papieża oraz w wyniku której powołano Kościół unicki (grekokatolicki). W XVIII w., po przystąpieniu biskupów prawosławnych z Przemyśla do Kościoła unickiego wyznanie to zostało narzucone całej społeczności łemkowskiej (Nowakowski 1992: 314

). Przez cały ten czas jednym z głównych czynników, który umożliwił im zachowanie poczucia odrębności, było wyznanie prawosławne. Wydarzeniem, które miało w znacznym stopniu wpłynąć na historię Łemków, było zatem zawarcie unii brzeskiej w 1596 r., zgodnie z postanowieniami której część duchowych prawosławnych w Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów uznała zwierzchnictwo papieża oraz w wyniku której powołano Kościół unicki (grekokatolicki). W XVIII w., po przystąpieniu biskupów prawosławnych z Przemyśla do Kościoła unickiego wyznanie to zostało narzucone całej społeczności łemkowskiej (Nowakowski 1992: 314 Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

).

).Uwłaszczenie chłopstwa w Austrii, które miało miejsce w 1848 r, spowodowało w II połowie XIX w. znaczne rozdrobnienie wsi i wzrost bezrobocia na terenie Galicji oraz na Łemkowszczyźnie. Wywołało to emigrację zarobkową do obu Ameryk (Nowakowski 1992: 314

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

). Zjawisko można uznać za masowe – jeszcze przed rozpoczęciem I wojny światowej do Stanów Zjednoczonych wyemigrowało około 225 000 Rusinów (Magocsi 1999a: 98

). Zjawisko można uznać za masowe – jeszcze przed rozpoczęciem I wojny światowej do Stanów Zjednoczonych wyemigrowało około 225 000 Rusinów (Magocsi 1999a: 98 Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul 1999a. “The Rusyn Language Question Revisited (1995)”, w: Paul Magocsi (red.) Of the Making of Nationalities I. New York: Columbia University Press/East European Monographs, s. 86-111.

).

).Druga połowa XIX w. to także okres budzenia się narodowej świadomości Łemków i Ukraińców oraz okres rywalizacji pomiędzy orientacją proukraińską, którą reprezentowało m.in. towarzystwo Proswita, a starorusińską (Towarzystwo im. Michaiła Kaczkowskiego), z której następnie wykształciło się również ugrupowanie prorosyjskie (por. Moklak 1997: 19-27

Moklak 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Moklak 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Moklak, Jarosław 1997. Łemkowszczyzna w II Rzeczypospolitej. Zagadnienia polityczne i wyznaniowe. Kraków: Historia Jagiellonica.

; Nowakowski 1992: 314-316

; Nowakowski 1992: 314-316 Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

; Duć-Fajfer 2001: 17-31

; Duć-Fajfer 2001: 17-31 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

). Poszczególne orientacje narodowe omówione zostały dalej.

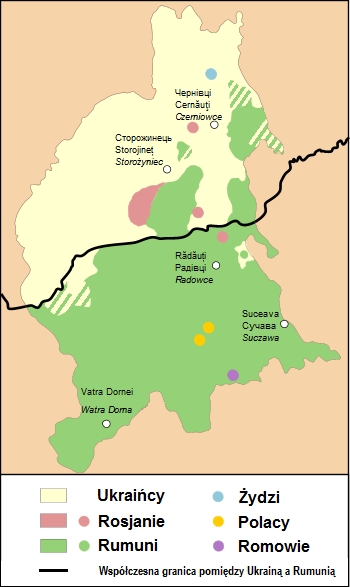

). Poszczególne orientacje narodowe omówione zostały dalej.Również badania dotyczące charakterystyki etnograficznej, rozpoczęte w XIX w., potwierdzają ciągłość zmian tożsamości narodowej. Od początku problem dla badaczy stanowiło wyznaczenie granicy pomiędzy ludnością rusińską a pozostałymi grupami ludności wschodniosłowiańskiej. O ile jednak przez cały XX w. rosła wśród osób zamieszkujących północną część Galicji liczba deklarujących przynależność do narodu ukraińskiego, a pod koniec XX w. praktycznie cała ludność zamieszkująca Galicję Wschodnią i Bukowinę Północną uważała się za Ukraińców (Magocsi 2004: 17

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

), o tyle Łemkowie w pierwszych dwóch dekadach XX w. sprzyjali ruchowi prorosyjskiemu (Moklak 1997: 25-27

), o tyle Łemkowie w pierwszych dwóch dekadach XX w. sprzyjali ruchowi prorosyjskiemu (Moklak 1997: 25-27 Moklak 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Moklak 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Moklak, Jarosław 1997. Łemkowszczyzna w II Rzeczypospolitej. Zagadnienia polityczne i wyznaniowe. Kraków: Historia Jagiellonica.

), a w okresie późniejszym w znacznej części przyjęli tożsamość odrębną (Duć-Fajfer 2002: 26

), a w okresie późniejszym w znacznej części przyjęli tożsamość odrębną (Duć-Fajfer 2002: 26 Duć-Fajfer 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2002. Czy to tęsknota czy nadzieja? Antologia powysiedleńczej literatury łemkowskiej w Polsce. Legnica: Stowarzyszenie Łemków.

).

). Położenie Galicji Wschodniej na mapie współczesnej Ukrainy (http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Ukraine-Halychyna.png&filetimestamp=20090407203404).

Położenie Galicji Wschodniej na mapie współczesnej Ukrainy (http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Ukraine-Halychyna.png&filetimestamp=20090407203404).

Główne grupy etniczne na terenie Bukowiny (red.mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz, na podstawie: http://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Bucovethn.png).

Podczas I wojny światowej na Łemków, oskarżonych o nastawienie prorosyjskie, spadły represje austriackie. W obozie Talerhof (łemk. Талергоф) w pobliżu miasta Graz (w Austrii) osadzono łącznie od dwóch (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 24

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

) do pięciu (Reinfuss 1990: 122

) do pięciu (Reinfuss 1990: 122 Reinfuss 1990 / komentarz/comment/r /

Reinfuss 1990 / komentarz/comment/r / Reinfuss, Roman 1990. Śladami Łemków. Warszawa: PTTK „Kraj”.

) tysięcy osób pochodzenia łemkowskiego, w tym przede wszystkim chłopów, a także przedstawicieli inteligencji - nauczycieli, urzędników oraz księży (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 23-24

) tysięcy osób pochodzenia łemkowskiego, w tym przede wszystkim chłopów, a także przedstawicieli inteligencji - nauczycieli, urzędników oraz księży (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 23-24 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

; Nowakowski 1992: 315

; Nowakowski 1992: 315 Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

). Z ówczesnymi prześladowaniami Łemków związana jest też osoba łemkowskiego świętego – Maksyma Gorlickiego (właśc. Maksyma Sandowycza – łem. Максим Сандович), który został w dniu 6 września 1914 r. bez wydania wyroku sądowego czy przeprowadzenia dochodzenia rozstrzelany na mocy decyzji austriackiego oficera w związku z podejrzeniami o sympatie prorosyjskie (http://www.pravoslavie.ru/orthodoxchurches/40006.htm).

). Z ówczesnymi prześladowaniami Łemków związana jest też osoba łemkowskiego świętego – Maksyma Gorlickiego (właśc. Maksyma Sandowycza – łem. Максим Сандович), który został w dniu 6 września 1914 r. bez wydania wyroku sądowego czy przeprowadzenia dochodzenia rozstrzelany na mocy decyzji austriackiego oficera w związku z podejrzeniami o sympatie prorosyjskie (http://www.pravoslavie.ru/orthodoxchurches/40006.htm).

Tzw. Krzyż talerhofski w Lesznie w powiecie przemyskim.

Pod koniec 1918 r., wykorzystując okazję powstałą w wyniku rozpadu Monarchii Austro-Węgierskiej, Łemkowie rozpoczęli działania polityczne mające na celu stworzenie odrębnego organizmu państwowego. Powstały wówczas dwie republiki łemkowskie. Proukraińska Republika Komańczańska istniała od 5 listopada 1918 r. do 27 stycznia 1919 r. z siedzibą w Komańczy; na czele republiki stanął jako prezydent Andrij Kyr. Zgłosiła ona akces do Zachodnioukraińskiej Republiki Ludowej, do końca 1918 r. obejmując ponad 35 wsi powiatu sanockiego; przestała istnieć w dniu 27 stycznia 1919 r., po interwencji oddziałów polskich (Nowakowski 1992: 316-318

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

).

).W czasie powstawania Republiki Komańczańskiej, w związku z uzyskaniem gwarancji otrzymania autonomii przez Rusinów w granicach Czechosłowacji (Magocsi 2004: 31

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

), Łemkowie z powiatów gorlickiego, jasielskiego i krośnieńskiego w dniu 5 grudnia 1918 r. proklamowali powstanie niezależnej Rusińskiej Ludowej Republiki Łemków ze stolicą we Florynce (łemk. Флоринка). Istniała ona do końca marca 1920 r., kiedy to na teren Republiki wkroczyły wojska polskie (Nowakowski 1992: 318-321

), Łemkowie z powiatów gorlickiego, jasielskiego i krośnieńskiego w dniu 5 grudnia 1918 r. proklamowali powstanie niezależnej Rusińskiej Ludowej Republiki Łemków ze stolicą we Florynce (łemk. Флоринка). Istniała ona do końca marca 1920 r., kiedy to na teren Republiki wkroczyły wojska polskie (Nowakowski 1992: 318-321 Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

).

).Lata 1920-te to okres wzmożonej emigracji Łemków do Kanady i Stanów Zjednoczonych (Nowakowski 1992: 326

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

). W tym czasie bardzo intensywnie rozwijała się również łemkowska publicystyka. Nowakowski (1992: 327

). W tym czasie bardzo intensywnie rozwijała się również łemkowska publicystyka. Nowakowski (1992: 327 Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

) wymienia następujące tytuły: Diło, Hołos, Hołos Ukraiński, Hołos Narodu, Nedila, Prawda, Selrob, Beskid, Seło, Łemko (wydawany na terenie Stanów Zjednoczonych), Ziemia i Wola, Narodna Wola.

) wymienia następujące tytuły: Diło, Hołos, Hołos Ukraiński, Hołos Narodu, Nedila, Prawda, Selrob, Beskid, Seło, Łemko (wydawany na terenie Stanów Zjednoczonych), Ziemia i Wola, Narodna Wola.W latach 1930-tych język łemkowski wprowadzono do szkół, zezwolono też na działanie organizacji łemkowskich (Magocsi 2004: 33

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). Ponadto w następstwie tzw. wojny religijnej (konwersji znacznej części ludności łemkowskiej na prawosławie) utworzona została Apostolska Administracja Łemkowszczyzny, w związku z czym Łemkowie wyjęci zostali spod kontroli proukraińskiej grekokatolickiej eparchii (diecezji) w Przemyślu (Nowakowski 1992: 339-340

). Ponadto w następstwie tzw. wojny religijnej (konwersji znacznej części ludności łemkowskiej na prawosławie) utworzona została Apostolska Administracja Łemkowszczyzny, w związku z czym Łemkowie wyjęci zostali spod kontroli proukraińskiej grekokatolickiej eparchii (diecezji) w Przemyślu (Nowakowski 1992: 339-340 Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nowakowski 1992 / komentarz/comment/r / Nowakowski, Krzysztof 1992. „Sytuacja polityczna na Łemkowszczyźnie w latach 1918-1939”, w: J. Czajkowski (red.) Łemkowie w historii i kulturze Karpat. Cz. I. Rzeszów: Editions Spotkania, s. 313-350.

).

).Po wybuchu II wojny światowej tereny zamieszkane przez Łemków włączone zostały w większości do Generalnego Gubernatorstwa III Rzeszy. W okresie tym pogłębił się wśród Łemków podział postaw narodowych – mino narzucenia Łemkowszczyźnie administracji ukraińskiej, m.in. w zakresie szkolnictwa, część lokalnej ludności jeszcze intensywniej opierała się przymusowej ukrainizacji (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 26

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

).Po zakończeniu wojny około dwie trzecie Łemków przesiedliła się (początkowo dobrowolnie, w okresie późniejszym przesiedlenia nabrały znamion przymusu ze strony władz) na teren Ukraińskiej Socjalistycznej Republiki Radzieckiej. Później, począwszy od 1947 r., w ramach Akcji „Wisła”, pozostała ludność łemkowska przesiedlona została niemal w całości na teren tzw. Ziem Odzyskanych, przede wszystkim na teren Dolnego Śląska. Ponadto w wyniku przeprowadzenia Akcji „Wisła” i wprowadzeniu zakazu przemieszczania się ludności oraz księży unickich uniemożliwiono działalność duszpasterską Kościoła grekokatolickiego (Orłowska 2012: 110-112

Orłowska 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Orłowska 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Orłowska, Beata 2012. “Sytuacja wyznaniowa wśród Łemków na ziemiach zachodnich w latach 1947-1956”, w: Bogusław Drożdż (red.) Perspectiva: Legnickie Studia Teologiczno-Historyczne XI/20: 106-118.

), a Łemkowie uznani zostali za mniejszość ukraińską. Części z nich udało się wrócić na Łemkowszczyznę – do lat 1980-tych na terenach rodzimych znalazło się ponownie ok. 10 000 Łemków (Magocsi 2004: 35

), a Łemkowie uznani zostali za mniejszość ukraińską. Części z nich udało się wrócić na Łemkowszczyznę – do lat 1980-tych na terenach rodzimych znalazło się ponownie ok. 10 000 Łemków (Magocsi 2004: 35 Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). Powracający Łemkowie nie mogli liczyć na żadną formę pomocy ze strony państwa, musieli zazwyczaj odkupywać lub odbudowywać swoje gospodarstwa. Chomiak (1995: 93-100

). Powracający Łemkowie nie mogli liczyć na żadną formę pomocy ze strony państwa, musieli zazwyczaj odkupywać lub odbudowywać swoje gospodarstwa. Chomiak (1995: 93-100 Chomiak 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Chomiak 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Chomiak, Roman 1995. Nasz łemkowski los. Nowy Sącz: Sądecka Oficyna Wydawnicza Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury.

) w swojej autobiograficznej relacji zamieszcza m.in. korespondencję z organami polskiej administracji państwowej z lat 1960 – 1988. W odpowiedziach, powołując się na obowiązujące prawo, poszczególne instytucje odmawiały wszczęcia postępowania mającego na celu zwrot wywłaszczonego gospodarstwa Chomiaka znajdującego się na Łemkowszczyźnie.

) w swojej autobiograficznej relacji zamieszcza m.in. korespondencję z organami polskiej administracji państwowej z lat 1960 – 1988. W odpowiedziach, powołując się na obowiązujące prawo, poszczególne instytucje odmawiały wszczęcia postępowania mającego na celu zwrot wywłaszczonego gospodarstwa Chomiaka znajdującego się na Łemkowszczyźnie.Ponadto po 1945 r., język łemkowski podobnie jak większość odmian rusińskich w pozostałych krajach bloku komunistycznego (a więc w ZSRR, Czechosłowacji, Węgrzech), uznany został za dialekt języka ukraińskiego. Mimo ciągłego użycia w codziennych sytuacjach komunikacyjnych język Łemków nie był nauczany w szkołach, a wszelkie publikacje tworzone po łemkowsku musiały być ukrainizowane (Magocsi 2004: 9

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). Wprowadzano zatem zmiany w pisowni, tak aby bardziej przypominała ona ukraińską (np. usuwano literę < ы>, wprowadzano literę <ї>), usuwano słowo Rusin, a w jego miejsce wstawiano Ukrainiec (Michna 1995: 50-51

). Wprowadzano zatem zmiany w pisowni, tak aby bardziej przypominała ona ukraińską (np. usuwano literę < ы>, wprowadzano literę <ї>), usuwano słowo Rusin, a w jego miejsce wstawiano Ukrainiec (Michna 1995: 50-51 Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Michna, Ewa 1995. Łemkowie: Grupa etniczna czy naród? Kraków: Nomos.

). Dodatkowo w 1952 r. Łemkowie objęci zostali systemem szkolnictwa mniejszościowego dla mniejszości ukraińskiej, dość niechętnie uczestniczyli jednak w zajęciach. Jak pisze Pudło (1987: 123-126

). Dodatkowo w 1952 r. Łemkowie objęci zostali systemem szkolnictwa mniejszościowego dla mniejszości ukraińskiej, dość niechętnie uczestniczyli jednak w zajęciach. Jak pisze Pudło (1987: 123-126 Pudło 1987 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pudło 1987 / komentarz/comment/r / Pudło, Kazimierz 1987. Łemkowie: Proces wrastania w środowisko Dolnego Śląska 1947-1985. Wrocław: Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze.

): „Sytuacja ukraińskiego szkolnictwa na Dolnym Śląsku była (...) trudniejsza niż na przykład w Olsztyńskim czy Szczecińskim (...) przede wszystkim z uwagi na brak większego zainteresowania nauką języka ukraińskiego ze strony przeważającej tutaj ludności łemkowskiej. (…) W niektórych szkołach byłych powiatów górowskiego, lubińskiego, oleśnickiego i wołowskiego młodzież za namową rodziców odmawiała uczęszczania na zajęcia z języka ukraińskiego (...) twierdząc, że nie są Ukraińcami, lecz Łemkami”.

): „Sytuacja ukraińskiego szkolnictwa na Dolnym Śląsku była (...) trudniejsza niż na przykład w Olsztyńskim czy Szczecińskim (...) przede wszystkim z uwagi na brak większego zainteresowania nauką języka ukraińskiego ze strony przeważającej tutaj ludności łemkowskiej. (…) W niektórych szkołach byłych powiatów górowskiego, lubińskiego, oleśnickiego i wołowskiego młodzież za namową rodziców odmawiała uczęszczania na zajęcia z języka ukraińskiego (...) twierdząc, że nie są Ukraińcami, lecz Łemkami”.Sytuacja Łemków poprawiła się w latach 1980-tych. W 1983 r. po raz pierwszy zorganizowano we wsi Czarne (ros. Чорне) Watrę – festiwal kulturowo-folklorystyczny, odbywający się na terenie Łemkowszczyzny (Magocsi 2004: 36

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). W 1989 r. (http://www.stowarzyszenielemkow.pl/new/modules/publisher/item.php?itemid=19) powstało Stowarzyszenie Łemków, mające na celu rozwój kultury łemkowskiej oraz budowanie świadomości odrębności etnicznej grupy, które wkrótce rozpoczęło m.in. wydawanie czasopisma Бесіда (Besida). W tym samym czasie powstało także Zjednoczenie Łemków jako organizacja o orientacji proukraińskiej (Magocsi 2004: 36

). W 1989 r. (http://www.stowarzyszenielemkow.pl/new/modules/publisher/item.php?itemid=19) powstało Stowarzyszenie Łemków, mające na celu rozwój kultury łemkowskiej oraz budowanie świadomości odrębności etnicznej grupy, które wkrótce rozpoczęło m.in. wydawanie czasopisma Бесіда (Besida). W tym samym czasie powstało także Zjednoczenie Łemków jako organizacja o orientacji proukraińskiej (Magocsi 2004: 36 Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). Obecnie Łemkowie posiadają w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej status mniejszości etnicznej (Dz.U. 2005 Nr 17, poz. 141, z późn. zm.).

). Obecnie Łemkowie posiadają w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej status mniejszości etnicznej (Dz.U. 2005 Nr 17, poz. 141, z późn. zm.).W 1991 r. odbył się w Medzilaborcach (rusiń. Меджильабірці, Słowacja) Światowy Kongres Rusinów, którego jednym z inicjatorów było Stowarzyszenie Łemków (http://www.stowarzyszenielemkow.pl/new/modules/ publisher/item.php?itemid=296). W 1992 r. w miejscowości Bardejovské Kúpele (rusiń. Бардеёвскы Купелї/Bardejów-Zdrój) w Słowacji miał miejsce I Kongres Języka Rusińskiego, na którym postanowiono stworzyć wspólny język literacki Rusinów. Przyjęto na nim tzw. zasadę retoromańską, zgodnie z którą w każdym kraju, gdzie używane są odmiany języka rusińskiego (Polska, Słowacja, Ukraina, była Jugosławia), opracowana miała zostać lokalna norma literacka, a następnie na jej podstawie stworzony miał zostać jeden język literacki (Magocsi 2004: 9

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski.

). W lipcu 2011 r. odbył się w Budapeszcie XI Światowy Kongres Rusinów (www.stowarzyszenielemkow.pl/new/modules/publisher/item.php?itemid=297).

). W lipcu 2011 r. odbył się w Budapeszcie XI Światowy Kongres Rusinów (www.stowarzyszenielemkow.pl/new/modules/publisher/item.php?itemid=297).Kod ISO

rusiński kompleks językowy:

| ISO 639-3 | rue |

| SIL | RUE |

- wywiad z ks. A.Grabanem w Strzelcach Krajeńskich

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- tekst ustawy w języku łemkowskim

- Rieger 1995

- Łesiw 1997

- Połowinkin 1896

- Lewicki 1834

- Werchratski 1902

- Stieber 1982

- Zubrzycki 1837

- Czajkowski 1999

- Reinfuss 1961

- Duć-Fajfer 2001

- GUS RP 1938

- GUS RP 1938a

- Nowakowski 1992

- Magocsi 1999a

- Duć-Fajfer 2002

- Reinfuss 1990

- Rybakow 1983

- Orłowska 2012

- Łesiw 2009

- Dulichenko 2006

- Michna 1995

- Pudło 1987

- Duć-Fajfer 1998

- Moklak 1997a

- Mazurowska 2009

- Myszanycz 1997

- Kuzio 2005

- Fontański 2004

- Wańko 2004

- Plišková 2008

- Horbal 1997

- Duć-Fajfer 2004

- Chomiak 2003

- Chomiak 2004

- Fontański i Chomiak 2000

- Chomiak 1995

- Chomiak 2004a

- Chomiak 2005

- Dubec 2007

- Ziłyński 1934

- Ziłyński 1938

- Stieber 1959

- Narodowy Spis Ludności i Mieszkań 2011

- Arkuszyn 2009

- Pancio 2009

- Horszczak 1993

- Jabur 1994

- Jabur 2005

- Plišková 2008a

- Kerča 2004

- Kostelnik 1923

- Kočiš 1971

- Ramač 2002

- Oświata i wychowanie w roku szkolnym 2010/2011

- Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2012

- Chomiak 1992

- Magocsi 2004

- Moklak 1997

- Kedryn 1937

- Benedek 2004

- Duć-Fajfer 1993

- Duć-Fajfer 2006

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Mapa Łemkowszczyzny

- Osturna

- Mapka Rusi Szlachtowskiej

- Obszary zamieszkane przez Łemków i sąsiedzi

- Tereny zamieszkane przez Białych Chorwatów

- Bukowina

- Pomnik_ofiar_Talerhofu_we_wsi_Leszno

- Tablica gora Jawor

- Lemko_Tower

- Mapa zasięgu zapożyczeń na terenie Łemkowszczyzny

- Galicja wschodnia

- Horoszczak gramatyka

- Słownik łemkowsko-polski Horoszczaka

- Lemko Tower

- Tablica Regietów

- Tablica Nowica

- Besida nr 04

- Lemkiwśki Ricznyk 2009

- Płyta nagrobna Radocyna

- plakat łemkowski na Spis powszechny 2011