Lemko Rusyn

Affinity and Identity

Language family

The Lemko language is mentioned (as Lemko) twice in Ethnologue 2009 (http://www.ethnologue.com/ show_language.asp?code=rue) : in the list of languages used in Slovakia it is described as a dialect of the Rusyn language (http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=SK), while in the description of Belarus, “Lemko” is noted as alternative name of this language what should be classified as an error. The language classification of the Lemko according to Ethnologue is as follows:Indo-European → Slavic → East → Rusyn language/code RUE (language in Ukraine or language complex) → Lemko dialect

Observatoire linguistique does not mention the Lemko dialect.

(http://www.linguasphere.info/lcontao/tl_files/pdf/master/OL-SITE%201999-2000%20MASTER%20ONE%20Sectors%205-Zones%2050-54.pdf)

It specifies Rusyn-N (Northern Rusyn) as a dialect of the Rusyn language used on the territory of Poland. Rusyn-N can be heard in the areas of what used to be provinces of Krosno and Nowy Sącz, thus the two names can probably be equated. There is also a note saying that Rusyn-N in the area of Sanok is growing more and more similar to a transitory Rusyn-Polish.

Language or Group of dialects

The Lemko language was officially recognized as a language of an ethnic minority in Poland in 2005. There is still, however, a heated debate among scholars whether the Lemko dialects are:- a completely separate language system (Fontański i Chomiak 2000: 12

Fontański i Chomiak 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Fontański i Chomiak 2000 / komentarz/comment/r /

Fontański, Henryk & Mirosława Chomiak 2000. Gramatyka języka łemkowskiego. Katowice: Śląsk. ),

), - a local variety of the Rusyn language complex (Magocsi 2004: 106

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi, Paul (red.) 2004. Русыньскый язык. Najnowsze dzieje języków słowiańskich. Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski. ),

), - a dialect of the Ukrainian language (Łesiw 1997

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Українскі говірки у Польщі. Warszawa: Archiwum Ukraińskie. , Rieger 1995:10

, Rieger 1995:10 Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper. ).

).

Stieber 1982 / komentarz/comment/r /

Stieber 1982 / komentarz/comment/r / Stieber, Zdzisław 1982. Dialekt Łemków: Fonetyka i Fonologia. Wrocław: Polska Akademia Nauk.

; Magocsi 1999a: 88

; Magocsi 1999a: 88 Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul 1999a. “The Rusyn Language Question Revisited (1995)”, w: Paul Magocsi (red.) Of the Making of Nationalities I. New York: Columbia University Press/East European Monographs, s. 86-111.

).

The following elements point to the fact that the Lemko dialect is indeed a dialect of the Ukrainian language:

).

The following elements point to the fact that the Lemko dialect is indeed a dialect of the Ukrainian language:

- occurrence of the so-called pleophony (also known as ‘full vocalism’): linking of -ere-, -oro- like in the word sołoma („hay”);

- occurrence of an initial o- which equals Polish je- (Rieger 1995: 12

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper. );

); - a vast amount of vocabulary shared with the Ukrainian language; the number of words of Ukrainian origin in the Lemko language is much higher than from any other language (Rieger 1995: 16

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper. ).

).

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper.

) “affiliation of the Lemko dialect to the Ukrainian language area is a long-known academic fact” (1995: 10

) “affiliation of the Lemko dialect to the Ukrainian language area is a long-known academic fact” (1995: 10 Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper.

). Łesiw (1997: 48

). Łesiw (1997: 48 Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 1997. Українскі говірки у Польщі. Warszawa: Archiwum Ukraińskie.

) classifies Lemko as belonging to South-Western Ukrainian dialects, considering all the features differentiating Lemko from the standard variety of Ukrainian as unimportant (Łesiw 2009: 15-29

) classifies Lemko as belonging to South-Western Ukrainian dialects, considering all the features differentiating Lemko from the standard variety of Ukrainian as unimportant (Łesiw 2009: 15-29 Łesiw 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Łesiw 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Лесів, Михайло [Łesiw] 2009. „Основні характерні особливості системи лемківських говірок”, w: Олег Лещак (red.) Studia Methodologica XXVII: Лемківський діалект у загальноукраїнському контексті. Tarnopol: Редакційно-видавничий відділ ТНПУ ім.В. Гнатюка, s. 15-29.

).

).A contradictory approach is presented mainly by Rusyn researchers. Similarly to the political efforts to establish distinctive Lemko identity, these scholars argue that the Rusyn dialects, albeit similar to Ukrainian, should be considered a completely separate language system. The Rusyn dialects are gradually being codified, their literary output and prestige are growing (Magocsi 1999a: 110-111

Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul 1999a. “The Rusyn Language Question Revisited (1995)”, w: Paul Magocsi (red.) Of the Making of Nationalities I. New York: Columbia University Press/East European Monographs, s. 86-111.

) and the national self-awareness of the Rusyns have been awakened (Magocsi 1999a: 88

) and the national self-awareness of the Rusyns have been awakened (Magocsi 1999a: 88 Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r /

Magocsi 1999a / komentarz/comment/r / Magocsi, Paul 1999a. “The Rusyn Language Question Revisited (1995)”, w: Paul Magocsi (red.) Of the Making of Nationalities I. New York: Columbia University Press/East European Monographs, s. 86-111.

). According to this approach, the main varieties of the Rusyn language today are the following:

). According to this approach, the main varieties of the Rusyn language today are the following:- the Lemko language in Poland;

- a Rusyn language spoken in Slovakia, mainly in the Prešov Region (Prešovský kraj / Пряшівскый край);

- a Rusyn language spoken in Carpathian Ruthenia (ukr. Закарпаття, łem. Підкарпатя) in Ukraine;

- a Ruthenian language spoken in Serbia and Croatia.

Dulichenko 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Dulichenko 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Dulichenko, Aleksandr D. 2006. “The Language of Carpathian Rus’: Genetic Aspects”, w: Bogdan Horbal & Patricia A. Krafcik & Elaine Rusinko (red.) Carpatho-Rusyns and Their Neighbors: Essays in Honor of Paul Robert Magocsi. Fairfax: Eastern Christian Publications, s. 107-121.

) (they are described in more detail further on):

) (they are described in more detail further on):- occurrence of the phoneme [ы] (it does not occur in Ukrainian);

- using the suffix -oм with singular feminine nouns in Nominative;

- using the verb мати (“to have”), in contrast to the construction used in Ukrainian: у мене;

- lack of personal pronouns in verbal constructions;

- lexical borrowings from Polish, Slovak, Hungarian and Romanian, not found in the Ukrainian language.

When it comes to the internal diversification of the language used by Lemkos, phonological differences are most often seen as the main issue. These include, for example, the change of [i] into a vowel between [i] and [ɨ] in the West and something closer to [ɨ] in the East; or change of [sk] followed by [i] into [ɕʨ] in the West and [sќ] in the East of Lemkovina; as well as the pronunciation of [ł]: either as a Ukrainian ‘dark l’, or a 'hard l', or the-so called non-syllabic [u̯] as in the Polish word auto (Rieger 1995: 13-14

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper.

). Similar changes happened to inflectional endings of some verbs, for example, maty, znaty, which in the first person singular were changed to mam, znam, in the West, and maw, znaw in the East. Differences are also encountered when it comes to vocabulary, for example, the word for "potatoes" was dependant on the part of Lemkovina – gruli, kompery or bandurkы could all be heard (Rieger 1995: 15

). Similar changes happened to inflectional endings of some verbs, for example, maty, znaty, which in the first person singular were changed to mam, znam, in the West, and maw, znaw in the East. Differences are also encountered when it comes to vocabulary, for example, the word for "potatoes" was dependant on the part of Lemkovina – gruli, kompery or bandurkы could all be heard (Rieger 1995: 15 Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper.

).

).

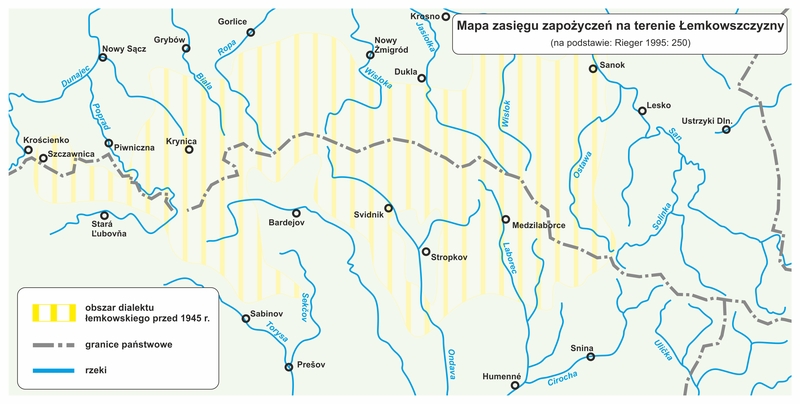

Map of the range of Lemko dialect before 1945 (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, based on: Rieger 1995: 250

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper.

).

).Identity – characteristic features

The Lemkos were significantly different ethnographically from the neighbouring peoples. There were distinct features in their rural settlements and the look of their crofts, the architecture of Lemko Orthodox churches, the Lemko folk costumes, as well as their faith, in which one can see the remnants of the former worship cult of nature (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 11-13 Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

).A characteristic feature that distinguished the Lemkos from their Western Slavic neighbours was, alongside language differences, their separate faith. After adopting Christianity, the Lemkos were part of the Orthodox Church, and since the 18th century they were forced to accept the Uniate Church. Even during the time when the majority of the Lemkos were part of the Uniate Church, they encountered persecution from the Roman Catholic Polish majority. The beginning of the 20th century brought an increasing number of conversions to the Orthodox Church. It can be associated with several factors, including the Lemkos’ fondness of this faith and the resistance against the Ukrainophile agitation led by some clergymen in the Greek Catholic eparchy of Przemyśl. In the face of the attempts to Ukrainize the Greek Catholic Church, conversion to the Orthodox Church was a means of maintaining the Lemkos’ identity by being closer to Russia. The first conversions to the Orthodox Church took place before the beginning of World War I, for instance in Grab (Граб) in 1911 and in Świątkowa (Святкова) in 1912. The process intensified during the so-called religious war in the years 1926-1928, after which it started to decline and finally stopped after the commission of the Apostolic Administration for the Lemkos which was directly under papal jurisdiction in 1934. Around 20 000 Lemkos converted to the Orthodox Church. As a result, there was a division among the Lemkos, the majority of whom stayed in the Uniate Church, while a large group of them converted to the Orthodox Church (Duć-Fajfer 2001: 16-17

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Duć-Fajfer 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Duć-Fajfer, Helena 2001. Literatura łemkowska w drugiej połowie XIX i na początku XX wieku. Kraków: Polska Akademia Umieje̜tności.

).

).For the development of the Lemkos’ identity, the period directly after the resettlements to Ukraine and Operation Vistula was very important. It led to temporary disintegration of the group, which nevertheless quickly reorganised. Eventually, despite partial assimilation of the Lemkos to the Polish population (the actual scope of assimilation is not known, because no exact research has been conducted in this matter – cf. Michna 1995: 51

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Michna, Ewa 1995. Łemkowie: Grupa etniczna czy naród? Kraków: Nomos.

), the resettlements caused a significant rise in the group’s national consciousness. It was caused by the locals’ reluctance towards the resettled people, which contributed to the Lemkos’ sense of distinctiveness from the Poles, and a negative stereotype of a Ukrainian propagated by the authorities which encouraged the members of the group to declare themselves “Lemkos” rather than “Ukrainians”. Furthermore, the Ukrainian influence was weakened by the actions of the Polish authorities aiming at the destruction of the Greek Catholic Church (Michna 1995: 51-52

), the resettlements caused a significant rise in the group’s national consciousness. It was caused by the locals’ reluctance towards the resettled people, which contributed to the Lemkos’ sense of distinctiveness from the Poles, and a negative stereotype of a Ukrainian propagated by the authorities which encouraged the members of the group to declare themselves “Lemkos” rather than “Ukrainians”. Furthermore, the Ukrainian influence was weakened by the actions of the Polish authorities aiming at the destruction of the Greek Catholic Church (Michna 1995: 51-52 Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Michna, Ewa 1995. Łemkowie: Grupa etniczna czy naród? Kraków: Nomos.

).

).On new areas, the Lemkos met with the national categorization of the world. Thus, they were forced to identify themselves in the new reality, where the old approach, sufficient in the traditional, rural environment, was not enough. The Lemkos – especially the young intellectuals – strive to find an appropriate ethos that would allow the group to form a complete national identity. Part of the Lemkos consider themselves the fourth Eastern Slavic nation, alongside the Russians, the Belarusians and the Ukrainians. The rest of the community see themselves as a part of the Ukrainian nation (Michna 1995: 52

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Michna, Ewa 1995. Łemkowie: Grupa etniczna czy naród? Kraków: Nomos.

). Ukrainian researchers (Myszanycz 1997

). Ukrainian researchers (Myszanycz 1997 Myszanycz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r /

Myszanycz 1997 / komentarz/comment/r / Мишанич, Олекса [Myszanycz] 1997. “Political Ruthenienism – A Ukrainian Problem”, The Ukrainian Quarterly LIII: 234-43.

; Kuzio 2005

; Kuzio 2005 Kuzio 2005 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kuzio 2005 / komentarz/comment/r / Kuzio, T. 2005. “The Rusyn question in Ukraine: Sorting out fact from fiction”, Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism XXXII: 17-29.

) claimed that the attempts to create the Rusyn nation are equal to forcing this ethnic identity on people who consider themselves Ukrainian.

) claimed that the attempts to create the Rusyn nation are equal to forcing this ethnic identity on people who consider themselves Ukrainian.Up to this day, the division among the group can be seen (Rieger 1995: 7

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Rieger 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Rieger, Janusz 1995. Słownictwo i nazewnictwo łemkowskie. Warszawa: Semper.

, Michna 1995: 7

, Michna 1995: 7 Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Michna, Ewa 1995. Łemkowie: Grupa etniczna czy naród? Kraków: Nomos.

), especially as it intensified in the democratic environment after the collapse of communism in Poland (Michna 1995: 52

), especially as it intensified in the democratic environment after the collapse of communism in Poland (Michna 1995: 52 Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r /

Michna 1995 / komentarz/comment/r / Michna, Ewa 1995. Łemkowie: Grupa etniczna czy naród? Kraków: Nomos.

).

).

ISO Code

the Rusyn language-complex:

| ISO 639-3 | rue |

| SIL | RUE |

- wywiad z ks. A.Grabanem w Strzelcach Krajeńskich

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- tekst ustawy w języku łemkowskim

- Rieger 1995

- Łesiw 1997

- Połowinkin 1896

- Lewicki 1834

- Werchratski 1902

- Stieber 1982

- Zubrzycki 1837

- Czajkowski 1999

- Reinfuss 1961

- Duć-Fajfer 2001

- GUS RP 1938

- GUS RP 1938a

- Nowakowski 1992

- Magocsi 1999a

- Duć-Fajfer 2002

- Reinfuss 1990

- Rybakow 1983

- Orłowska 2012

- Łesiw 2009

- Dulichenko 2006

- Michna 1995

- Pudło 1987

- Duć-Fajfer 1998

- Moklak 1997a

- Mazurowska 2009

- Myszanycz 1997

- Kuzio 2005

- Fontański 2004

- Wańko 2004

- Plišková 2008

- Horbal 1997

- Duć-Fajfer 2004

- Chomiak 2003

- Chomiak 2004

- Fontański i Chomiak 2000

- Chomiak 1995

- Chomiak 2004a

- Chomiak 2005

- Dubec 2007

- Ziłyński 1934

- Ziłyński 1938

- Stieber 1959

- Narodowy Spis Ludności i Mieszkań 2011

- Arkuszyn 2009

- Pancio 2009

- Horszczak 1993

- Jabur 1994

- Jabur 2005

- Plišková 2008a

- Kerča 2004

- Kostelnik 1923

- Kočiš 1971

- Ramač 2002

- Oświata i wychowanie w roku szkolnym 2010/2011

- Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2012

- Chomiak 1992

- Magocsi 2004

- Moklak 1997

- Kedryn 1937

- Benedek 2004

- Duć-Fajfer 1993

- Duć-Fajfer 2006

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Mapa Łemkowszczyzny

- Osturna

- Mapka Rusi Szlachtowskiej

- Obszary zamieszkane przez Łemków i sąsiedzi

- Tereny zamieszkane przez Białych Chorwatów

- Bukowina

- Pomnik_ofiar_Talerhofu_we_wsi_Leszno

- Tablica gora Jawor

- Lemko_Tower

- Mapa zasięgu zapożyczeń na terenie Łemkowszczyzny

- Galicja wschodnia

- Horoszczak gramatyka

- Słownik łemkowsko-polski Horoszczaka

- Lemko Tower

- Tablica Regietów

- Tablica Nowica

- Besida nr 04

- Lemkiwśki Ricznyk 2009

- Płyta nagrobna Radocyna

- plakat łemkowski na Spis powszechny 2011