High German varieties outside Silesia

Name

In German

The term High German language (Hochdeutsch) is often identified with the standard literary German, which is the most common variation of (High) German.The term High Prussian (Hochpreußisch) was created at the end of the 19th century (Żebrowska 2002: 38

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

). This variation was also called Breslausch or simply Ermländisch “Warmian” - the latter is considered imprecise by Ewa Żebrowska (2002: 38

). This variation was also called Breslausch or simply Ermländisch “Warmian” - the latter is considered imprecise by Ewa Żebrowska (2002: 38 Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

), as in northern and southern-east Warmia people spoke the Low German variations (which are described in a separate profile).

), as in northern and southern-east Warmia people spoke the Low German variations (which are described in a separate profile).Anton Kolberg believed that the ethymology of the term Breslausch refers to the word Prezla, which comes from a Baltic language - (Old) Prussian and means ‘country’ Prussia/Preußen. Other researchers associated this term and the origins of the dialect with Wrocław (German: Breslau) (Żebrowska 2002: 39

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

).

).The Palatine German language (one of the High German variations, used in Galicia) is named Pälzisch (in Palatine) / Pfälzisch (in Standard German) - this difference is caused by the lack of the sound [pf] in Palatine German. The Swabian language (in German Schwäbisch) was the other High German variation used in Galicia.

It is worth noting that Hochdeutsch (High German) is commonly understood mainly as Standard German. It is indicated on the advertising banner of Baden-Württemberg, which suggests the ignorance of High German in this German state. This banner is only a part of the campaign, for which purpose also short-form advertising videos in the Swabian language were shot: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDGuSj_Xolo

The advertising banner of Baden-Württemberg :’We’ve learnt all. Except High German.’: (source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wirkoennenalles.jpg).

A similar notion is conveyed in the title of a popular Karl-Heinz Göttner’s publication Alles außer Hochdeutsch (Berlin: Ullstein Taschenbuchverlag, 2012), concerning (the current situation) of dialects in Germany.

Exonyms

The described linguistic complex is simply called in Polish: German. To contrast it with the Low German language, the term High German is used. The High German variations are further divided into Mitteldeutsch (Central German) and Oberdeutsch (Upper German). Historically, on the territory of Poland, both the dialects of Central German and the dialects of Upper German were used.As dialects names usually refer to geographical units (regions, towns), the Polish names are generally created ad hoc through the adverbial forms referring to a given area (e.g. Hochpreussisch – wysokopruski - High Prussian, Pfälzisch – palatynacki - Palatine German etc.)

In English it is called High German. Also in English, there are names for variations used in Poland, e.g. High Prussian, Palatine German.

In the Ethnologue, German is in a lower category than High German - the latter together with German creates Yiddish (Lewis et al. 2013

Lewis i in. 2013 / komentarz/comment/r /

Lewis i in. 2013 / komentarz/comment/r / Lewis, M. Paul i in. (red.) 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Dallas: SIL International. [http://www.ethnologue.com].

).

).

The High German variations on the territory of present-day Poland at the beginning of the 20th century. Except the High Prussian and Silesian dialects, the High German dialects occurred in linguistic islands.

(map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, based on: http://mitglied.multimania.de/pomerania2/hist_maps/survey/dialect2a.jpg)

History and Geopolitics

The history of German settlement on the territory of present-day Poland dates back to the ancient times, when the Gepids and the Goths settled in the Vistula basin (Mitzka 1959: Mitzka 1959 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1959 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1959. Grundzüge nordostdeutscher Sprachgeschichte. Marburg: Elwert.

7). The Rugians and the Burgundians lived a little further west. The Vandals lived to the south.

7). The Rugians and the Burgundians lived a little further west. The Vandals lived to the south.The Slavic expansion moved the border of the Germans’ settlement much further to the West, to the so-calledLimes Saxoniae, situated between Hamburg and Lübeck (in the language of Polabian Slavs Ljubice, in German Lübeck). In the following centuries, the border of Slavic and German settlement changed many times, covering many transitional areas, inhabited by the representatives of both groups.

Illustration. Urn with swastikas from the Łódzkie poviat. The Third Reich propaganda wanted to legitimate the invasion by using the traces of German settlement (sometimes only presumed) (photograph after: Kargel 1941: 31

Kargel 1941 / komentarz/comment/r /

Kargel 1941 / komentarz/comment/r / Kargel, Adolf 1941. „Das Litzmanstädter Gebiet ist germanische Urheimat“, w: H. Müller Der Osten des Warthelandes. Litzmannstadt: Reichspropagandaamt. 30-35.

)

)The presence of speakers of High German variations can be explained by:

- historical belonging of present-day Polish territory to German countries (e.g. Prussia) - this was connected with both spontaneous and planned Germanisation of non-German people, as well as immigration from other German countries,

- from the times of Casimirus the Great, founding cities under the German law (mostly under the Magdeburg Law; Czoernig 1857: 17

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czoernig, Karl, Freiherr von 1857. Ethnographie der Oesterreichischen Monarchie. 1. Band. Wien: Die Kaiserl. Koenigl. Direction der administrativen Statistik. ), which was also followed by the German migration,

), which was also followed by the German migration, - the loss of prestige of Low German, which coincided with the Reformation and giving High German the church language status.

Prussia

The High Prussian dialect originated from the German colonisation of Warmia, as a consequence of this land being conquered by the Teutonic Order in the Middle Ages (Żebrowska 2002: 19-20 Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

). Initially, the German language was spoken in linguistic islands (Żebrowska 2002: 23

). Initially, the German language was spoken in linguistic islands (Żebrowska 2002: 23 Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

). The settlers who spoke the Central German dialects came from Saxony and Silesia (Żebrowska 2002: 24

). The settlers who spoke the Central German dialects came from Saxony and Silesia (Żebrowska 2002: 24 Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

).

).Walther Mitzka saw the origins of the High Prussian variation in the dialects of Silesia and Lusatia (Żebrowska 2002: 39

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2002 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2002. Morphologie der ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Kolonialmundart von Sętal und Umkreis. Olsztyn: UWM.

). As Mitzka (1959: 83-84

). As Mitzka (1959: 83-84 Mitzka 1959 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1959 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1959. Grundzüge nordostdeutscher Sprachgeschichte. Marburg: Elwert.

) writes, the High Prussian dialect created the Central German continuum together with the Central German dialects of southern Wielkopolska and Silesia. This continuum was stopped by the expansion of Low German, which started in the 16th century. (Mitzka 1959: 84

) writes, the High Prussian dialect created the Central German continuum together with the Central German dialects of southern Wielkopolska and Silesia. This continuum was stopped by the expansion of Low German, which started in the 16th century. (Mitzka 1959: 84 Mitzka 1959 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1959 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1959. Grundzüge nordostdeutscher Sprachgeschichte. Marburg: Elwert.

).

).Galicia

On the 18th of June 1774 Maria Theresa issued a decree, which encouraged “merchants, artists, manufacturers, repairmen and craftsmen” to settle on the area of Galicia (Krämer 1979: IX Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1979. Unser Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der galizischen Pfälzer und Schwaben. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Hilfskomittee der Galiziendeutschen.

). The Catholics were allowed to settle on the total area of the country, the Evangelicals only in the cities Lviv/Lemberg, Jarosław/Jaroslau, Zamość/Samosch i Zaleszczyki/Salischtschyky, later also in Brody and in Kazimierz (at that time the suburbs of Cracov) – later the Joseph’s II decree guaranteed the Evangelicals the freedom of religion and the freedom to reside and settle. Moreover, the emperor invited farmers by offering them some benefits (e.g. release from corvee works for 6 years).

). The Catholics were allowed to settle on the total area of the country, the Evangelicals only in the cities Lviv/Lemberg, Jarosław/Jaroslau, Zamość/Samosch i Zaleszczyki/Salischtschyky, later also in Brody and in Kazimierz (at that time the suburbs of Cracov) – later the Joseph’s II decree guaranteed the Evangelicals the freedom of religion and the freedom to reside and settle. Moreover, the emperor invited farmers by offering them some benefits (e.g. release from corvee works for 6 years).In years 1782-1786 (under the reign of the emperor Joseph II), the German population of Galicia increased by 120 newly founded colonies (in total 14 699 people up to 1785) - mainly Wirtemebergan Evangelicals and reformed colonists from the Palatinate (Pfalz), but there were also Catholic settlers (Krämer 1979: I

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1979. Unser Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der galizischen Pfälzer und Schwaben. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Hilfskomittee der Galiziendeutschen.

X). At the end of the 18th century the total German population of Galicia amounted to 20.000 and it increased to 30.000 by the half of the 19th century (Czoernig 1857: 17

X). At the end of the 18th century the total German population of Galicia amounted to 20.000 and it increased to 30.000 by the half of the 19th century (Czoernig 1857: 17 Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r / Czoernig, Karl, Freiherr von 1857. Ethnographie der Oesterreichischen Monarchie. 1. Band. Wien: Die Kaiserl. Koenigl. Direction der administrativen Statistik.

). The additional influx of Germans took place after the left bank of Rhine was invaded by France (1801) and after Napoleon dissolved the clerical states in Palatinate (1803). It led to anxieties and forced part of the population to emigrate.

). The additional influx of Germans took place after the left bank of Rhine was invaded by France (1801) and after Napoleon dissolved the clerical states in Palatinate (1803). It led to anxieties and forced part of the population to emigrate.The settlement took place in east Galicia (the areas of present-day Poland and Ukraine). In western Galicia, German groups settled only in three areas: near Nowy Sącz/Neu Sandez, near Bochnia/Salzberg and in the triangle Vistula-San/Weichsel-Saan (Krämer 1979: IX

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1979. Unser Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der galizischen Pfälzer und Schwaben. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Hilfskomittee der Galiziendeutschen.

).

).The Polish-Ukrainian and the German-Ukrainian borders did not cross Galicia, where rather sporadic German linguistic islands occured. Czoernig (1857: 41-42

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r / Czoernig, Karl, Freiherr von 1857. Ethnographie der Oesterreichischen Monarchie. 1. Band. Wien: Die Kaiserl. Koenigl. Direction der administrativen Statistik.

) mentions the following German linguistic islands in the Cracow Administrative Area Krakauer Verwaltungsgebiet) according to the data from the second half of the 19th century:

) mentions the following German linguistic islands in the Cracow Administrative Area Krakauer Verwaltungsgebiet) according to the data from the second half of the 19th century:- traditional linguistic islands: Biała/Biala (described separately as part of Bielsko-Bialska linguistic island), Kęty/Liebenwerde, Andrychów/Andrichau, Zator, Oświęcim/Auschwitz and other towns from the former Duchy of Oświęcim and the Duchy of Zator; also the Cracow area, where Germans and Poles lived together since the 13th century,

- the towns, where German speaking population increased under Austrian domination: Wadowice/Frauenstadt, Myślenice, Wieliczka/Groß Salze, Bochnia/Salzberg, Wojnicz, Tymbark/Tannenberg, Stary i Nowy Sącz/Sandez, Ciężkowice/Hardenberg, Grybów/Grünberg, Rzeszów, Łańcut/Landshut, Przeworsk, Leżajsk/Lyschansk,

- the official settlements, dating back to the colonisation of Joseph II in the following districts: Bocheński, Sądecki, Tarnowski, Rzeszowski,

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r / Czoernig, Karl, Freiherr von 1857. Ethnographie der Oesterreichischen Monarchie. 1. Band. Wien: Die Kaiserl. Koenigl. Direction der administrativen Statistik.

) names the following districts:

) names the following districts:- Lviv and other big cities: Jarosław/Jaroslau, Przemyśl/Prömsel, Sądowa Wisznia, Żółkiew, Sambor/Sombor, Stara Sól, Staremiasto (Samborski district), Borynia,

- many colonies in the Lviv district

- settlements in the Przemyski and Żółkiewski districts,

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r /

Czoernig 1857 / komentarz/comment/r / Czoernig, Karl, Freiherr von 1857. Ethnographie der Oesterreichischen Monarchie. 1. Band. Wien: Die Kaiserl. Koenigl. Direction der administrativen Statistik.

), in the Ruthenian part of the Lviv’s Administrative District, Germans resided only in bigger towns (e.g. Brody, Tanopol/Dornfeld, Kołomyja/Kolomea), and in sparse smaller settlements.

), in the Ruthenian part of the Lviv’s Administrative District, Germans resided only in bigger towns (e.g. Brody, Tanopol/Dornfeld, Kołomyja/Kolomea), and in sparse smaller settlements.It is worth mentioning that German settlement on the area of Galicia, in a broad sense, started as early as in the Middle Ages. Walther Mitzka (1943: 78-79

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1943. Deutsche Mundarten. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

) in the registered the language preserved from that period in as many as 16 villages in the vicinity of Bielsko-Biała, in Łańcut and in the village Krzemienica. Mitzka assigned those local dialects to the Silesian dialect. Similarly, he considered the local dialects from southern Wielkopolska (reaching north to Poznań/Posen, where they were supposed to cross-border with East Pomeranian - the Low German dialect (Mitzka 1943: 64, 74

) in the registered the language preserved from that period in as many as 16 villages in the vicinity of Bielsko-Biała, in Łańcut and in the village Krzemienica. Mitzka assigned those local dialects to the Silesian dialect. Similarly, he considered the local dialects from southern Wielkopolska (reaching north to Poznań/Posen, where they were supposed to cross-border with East Pomeranian - the Low German dialect (Mitzka 1943: 64, 74 Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1943. Deutsche Mundarten. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

) to be the Silesian variations, and he believed that they spanned to Prussia. According to him, the High Prussian dialect had its source in Silesia and Lusatia (Mitzka 1943: 63, 71

) to be the Silesian variations, and he believed that they spanned to Prussia. According to him, the High Prussian dialect had its source in Silesia and Lusatia (Mitzka 1943: 63, 71 Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1943. Deutsche Mundarten. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

).

).Other regions

The geography of the German dialects has changed drastically since 1886, when the Prussian Settlement Committee started to settle farmers from various parts of German states - mainly from Westphalia.In southern East Prussia (Mazuria) people spoke High German, which origins were different: peasant settlers (most probably the Mazurians speaking Slavic languages, however Mitzka 1943

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1943. Deutsche Mundarten. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

does not mention them) adopted the dialect from burghers.

does not mention them) adopted the dialect from burghers.

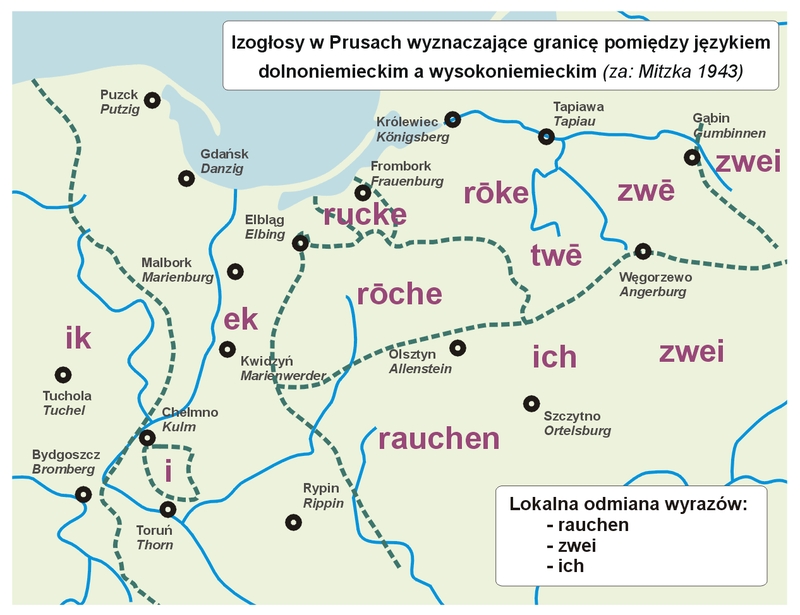

The isoglosses in Prussia designate the border between Upper and Lower German (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Mitzka 1943: 80a

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1943. Deutsche Mundarten. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

)

)At the latest, the High German language variation was formed in Łodź ~Lodsch. Until 1810, it was a small Polish settlement - Łodzia. A significant development of Łódź was related to the influx of the German speaking weavers from Silesia, Czech and Saxony and merchants from East Prussia, Rhineland, Swabia and Austria (Weigelt 2010: 50-51

Weigelt 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Weigelt 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Weigelt, Fritz 2010. „Der Lodzer Mensch”, w: E. Effenberger. Das Lodzerdeutsch. Mönchengladbach: Archiv der Deutschen aus Mittelpolen und Wolhynien. 50-55.

). Migrants from the Swabian-Rhineland bordeland settled around the city (Mitzka 1943: 78

). Migrants from the Swabian-Rhineland bordeland settled around the city (Mitzka 1943: 78 Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r /

Mitzka 1943 / komentarz/comment/r / Mitzka, Walther 1943. Deutsche Mundarten. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

).

).

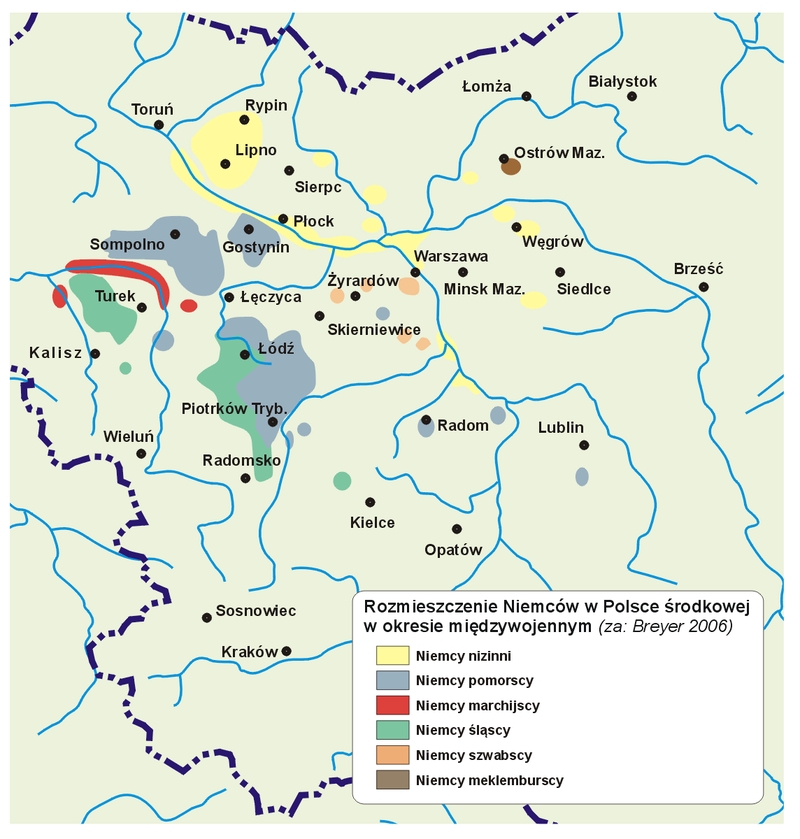

Germans in interwar Central Poland (map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz, after: Breyer 2006: 9

Breyer 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Breyer 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Breyer, Albert 2006. Deutsche Gaue in Mittelpolen. Seefeld [www.UsptreamVistula.org][http://rinwww.upstreamvistula.org/Documents/ABreyer_DtGaue.pdf].

).

).

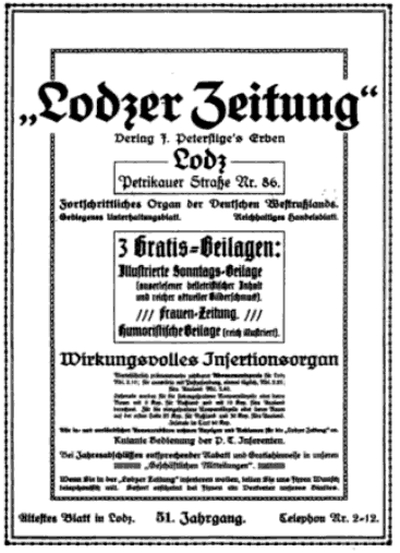

Lodzer Zeitung published since 1863, was probably the first magazine which appeared in Łódź (reprint after: Urban 2004: 166

Urban 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Urban 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Urban, Thomas 2004. Von Krakau bis Danzig: Eine Reise durch die deutsch-polnische Geschichte. München: Beck.

)

)At present-day Poland there are no areas densely inhabited by the speakers of the High German dialects, except the areas resided by the members of German minority in Silesia (primarily in Opolskie province).

(after: http://filozofiaslaska.blogspot.com/2010_12_01_archive.html)

Outside Poland

The Standard German language is an official language of several countries in Europe, as well as a recognised (minority) language in other regions of Europe and the world. The native High German dialects are spoken in Europe in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Liechtenstein but also in Czech, Denmark, France, Italy, Slovakia and Romania. The Swabian and Palatine German dialects are still used in the regions of their origins (e.g. Swabia, Palatine). Apart from the Galician dialects, also many other colonial dialects derived from them (e.g. in Kansas state http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/bitstream/1808/12493/4/Keel_slides.pdf)The East Central German dialect, brought by the settlers from Prussia and Silesia was spoken in southern Australia (Sprothen 2007

Sprothen 2007 / komentarz/comment/r /

Sprothen 2007 / komentarz/comment/r / Sprothen, Vera 2007. „Das deutsche Australien”, Die Welt 24.11.07. [http://www.welt.de/1395564].

). Peter Paul (1962

). Peter Paul (1962 Paul 1962 / komentarz/comment/r /

Paul 1962 / komentarz/comment/r / Paul, Peter 1962. Barossadeutsch: sprachliche Untersuchungen des ostmitteldeutschen Dialektes des Barossatales (Sudaustralien). Adelaide: University of Adelaide.

, 1965

, 1965 Paul 1965 / komentarz/comment/r /

Paul 1965 / komentarz/comment/r / Paul, Peter 1965. Das Barossadeutsche: Ursprung, Kennzeichen und Zugehorigkeit : Untersuchungen in einer deutschen Sprachinsel. Adelaide: University of Adelaide.

) described this dialect in his works. Works (e.g. poetry audio recordings) in Barossa Deutsch, local name for this dialect, can be found at the web portal Germany Down Under (http://germanydownunder.com/category/poetry/broken/). Moreover, its traces can be found in (English language) books of Colin Thiele, Australian writer.

) described this dialect in his works. Works (e.g. poetry audio recordings) in Barossa Deutsch, local name for this dialect, can be found at the web portal Germany Down Under (http://germanydownunder.com/category/poetry/broken/). Moreover, its traces can be found in (English language) books of Colin Thiele, Australian writer.ISO Code

ISO-639-3: German - deu,

Palatine - pfl,

Swabian - swb.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - ger;

historical variations are: gmh – Middle High German, goh – Old High German;

other German languages - gem.

SIL (13 ed. The Ethnologue): ger; at present The Ethnologue: deu.

Palatine - pfl,

Swabian - swb.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - ger;

historical variations are: gmh – Middle High German, goh – Old High German;

other German languages - gem.

SIL (13 ed. The Ethnologue): ger; at present The Ethnologue: deu.

- przyp01

- Żebrowska 2002

- Lewis i in. 2013

- Mitzka 1959

- Kargel 1941

- Krämer 1979

- Czoernig 1857

- Mitzka 1943

- Weigelt 2010

- Breyer 2006

- Urban 2004

- Sprothen 2007

- Paul 1962

- Paul 1965

- Finckh 1931

- Christmann 1931a

- Kollauer 1931

- Brubaker 1998

- Paradowska a

- Paradowska b

- Koerth 1929

- Pauls i Krahn 1956

- Bender i Bergmann 1987

- Kawski 2010

- Żebrowska 2004

- Krämer 1931

- Effenberger 2010

- Beck-Vellhorn i Scharlach 1936a

- Haeufler 1846

- Kossmann 1935

- Kłańska 1991

- Karasek-Langer i Strzygowski 1932

- Karasek-Langer Alfred i Elfriede Strzygowski 1938

- Goetze 1922

- Schmit 1942

- Beck-Vellhorn i Scharlach 1936b

- Müller 1962

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Baner reklamowy

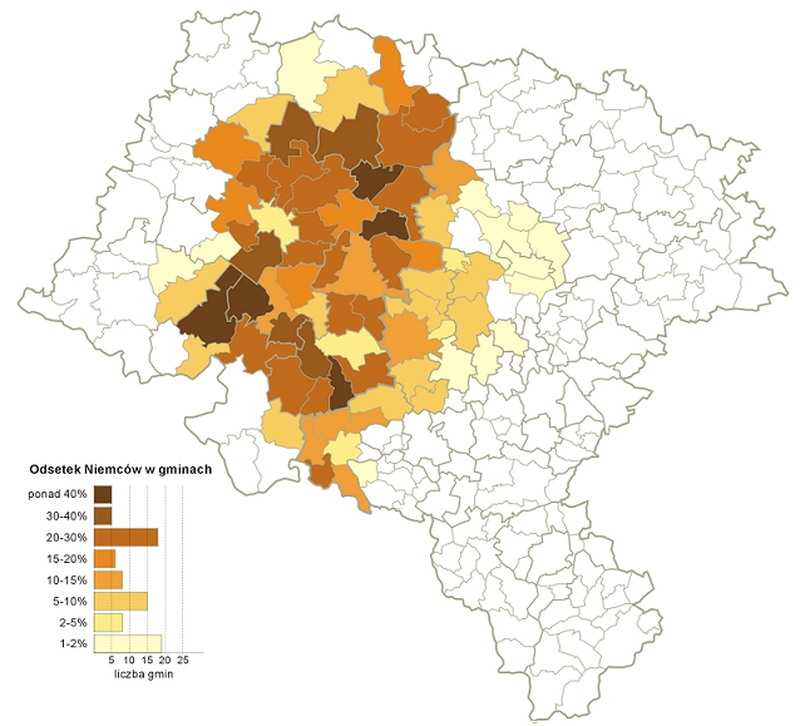

- Odsetek Niemców w gminach

- Odsetek Niemców w-m

- Gwary niemieckie w Polsce wg Maurmanna

- PGR-Arbeiter

- książka Göttnera

- Urna ze swastykami pochodząca z Łódzkiego

- Izoglosy w Prusach

- Rozmieszczenie Niemców w Polsce środkowej IIRP

- Lodzer Zeitung

- Galicyjskie dziewczęta przy pracy

- Współcześni Bambrzy

- Izoglosy w gwarach Galicji

- Tekst szryftem gotyckim

- Zapożyczenia polskie i ukraińskie

- Schemat maselnicy

- Zapożyczenia w gwarze łódzkiej

- Podania

- Analiza Krämera

- Pieśń z Woli-Oblasznicy

- Huasnpolka – szwabski taniec z Machlińca

- Granica dialektów w płn. Polsce

- tabela do gwar Galicji

- Milch w Biskupiej Górce