High German varieties outside Silesia

Linguistic overview

Typological classification

Similarly to the Standard High German, the presented variations belong to the inflected languages, i.e. verb inflection (tense, person) and nominal inflection (number, cases) etc. The High German dialects are predominantly S-V-O dialects (most frequently subject-verb-object, sometimes object-verb-subject), similarly to the related German languages.Ewa Żebrowska (2004

Żebrowska 2004 / komentarz/comment/r /

Żebrowska 2004 / komentarz/comment/r / Żebrowska, Ewa 2004. Die Äußerungsgliedfolge im Hochpreußischen. Olsztyn: UWM.

) in her work Die Äußerungsgliedfolge im Hochpreußischen analyses the syntax of the High Prussian dialect in a more detailed way.

) in her work Die Äußerungsgliedfolge im Hochpreußischen analyses the syntax of the High Prussian dialect in a more detailed way.Description of local dialects in the following areas

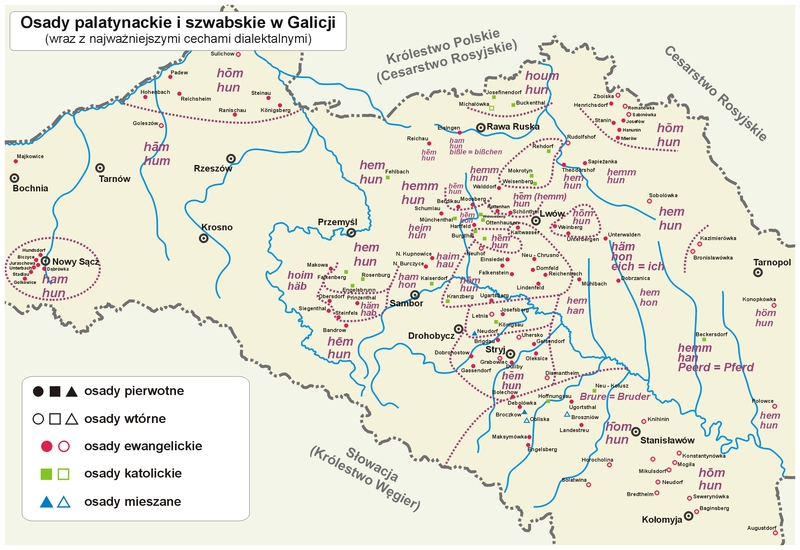

The Galician local dialects

The local dialects could vary significantly in various villages. Krämer (1979: XIII Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1979. Unser Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der galizischen Pfälzer und Schwaben. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Hilfskomittee der Galiziendeutschen.

) notes many differences within a relatively small area, where the Galician Palatinate local dialects were spoken. In Obliska, village of many denominations, and in Protestant settlements, people used ich hun (Standard ich habe ‘I have got’) and ich deet (standard ich inürde, while in Catholic villages people used ich hon and ich get respectively.

) notes many differences within a relatively small area, where the Galician Palatinate local dialects were spoken. In Obliska, village of many denominations, and in Protestant settlements, people used ich hun (Standard ich habe ‘I have got’) and ich deet (standard ich inürde, while in Catholic villages people used ich hon and ich get respectively.

#Palatynackie i szwabskie osady i gwary w Galicji - map and tabel ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz.

Distinctness from the original local dialects

In comparison with the original Palatinate German and Swabian local dialects, Krämer (1979: XVII-XX Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1979. Unser Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der galizischen Pfälzer und Schwaben. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Hilfskomittee der Galiziendeutschen.

) distinguishes the following phenomena, which influenced the distinctness of the Galician variations:

) distinguishes the following phenomena, which influenced the distinctness of the Galician variations:- the influence of the Standard German language - Galicia was not an united area in terms of a dialect, which resulted in the necessity to use the Standard High German language (just for communicating with a village nearby, with the city dwellers, or with a parish priest); speakers of local dialects pronounced the Standard language words in a local dialect manner, according to the dialectical phonetics - e.g. ü was replaced by i (Rübe>Ribe `turnip, beetroot‘), ö was replaced by e (Löcher>Lecher `holes‘), and äu/eu by ai (Häuser>Haiser `houses‘), ,

- the use of Austrian terminology to describe new phenomena (such as e.g. railway), hence e.g. Billet (‘ticket’), or Kupee (‘compartment’) - they were often borrowings, such as Kren (‘horseradish’, in Czech křen),

- the use of borrowings from the neighbouring Slavic languages, i.e. Polish and Ukrainian, e.g. Kummet (‘horse collar’) - very often not only a word was borrowed but also a cultural element described by it, e.g. np. Holobtsche (‘gołabki -meat-stuffed cabbage’, name of Ukrainian dish голубцi), Mamaliga (‘hominy’) ,

- the influence of Yiddish - according to Krämer, the Galician Germans borrowed around 60 Jewish words, e.g. ore (‘to hint’), bemsche (‘to pray, to whisper’) - very often those words are indispensable to describe the Jewish culture, e.g. Goi (‘Christian man=non-Jew’), koscher (‘kosher=ritually cleaned).

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1979. Unser Sprachschatz. Wörterbuch der galizischen Pfälzer und Schwaben. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Hilfskomittee der Galiziendeutschen.

).

).Linguistic overview of the Galician Swabian dialects

The most significant features of the Swabian dialects of Galicia, emphasised by Julius Krämer (1931 Krämer 1931 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1931 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1931. „Die „schwäbischen“ Mundarten in Galizien”, w: Gedenkbuch zur Erinnerung an die Einwanderung der Deutschen in Galizien vor 150 Jahren. Herausgegeben vom Ausschuß der Gedenkfeier. Posen: Verlag der Historischen Gesellschaft für Posen. 178-189.

) are presented below – the author stressed that the presented data may not fully reflect the diversity of the local dialects of Galicia, as they are only based on the material from 57 settlements.

) are presented below – the author stressed that the presented data may not fully reflect the diversity of the local dialects of Galicia, as they are only based on the material from 57 settlements.Phonetics

- Central High German (CHG) long [i] changed into Svabian-Galician [ai], e.g. ais ‘ice’, standard Eis, (=Standard German)

- CHG long [u] > Swabian-Galician [au], e.g. daube (‘pigeon’, standard Taube),

- CHG long [ü] >Swabian-Galician [ai], e.g. (‘today’, standard heute),

- CHG long [a] > Swabian-Galician [oo], e.g. joor (‘year’, standard Jahr),

- vowel rounding with umlaut , e.g. iwǝr (‘above’, standard über).

Krämer 1931 / komentarz/comment/r /

Krämer 1931 / komentarz/comment/r / Krämer, Julius 1931. „Die „schwäbischen“ Mundarten in Galizien”, w: Gedenkbuch zur Erinnerung an die Einwanderung der Deutschen in Galizien vor 150 Jahren. Herausgegeben vom Ausschuß der Gedenkfeier. Posen: Verlag der Historischen Gesellschaft für Posen. 178-189.

) noted the following phenomena concerning consonants:

) noted the following phenomena concerning consonants:- second consonant shift was complete only for [t], for [p] only in the final position and in the middle of the word after vowel and [l],[r], for [k] only afted vowel,

- Old German [b] into [w], e.g. Aarwǝd/Ärwǝd (‘work’, standard Arbeit) – w can be considered classical labial fricative, as well as labiodental consonant, borrowed from the Standard German language or Slavic languages,

- pra-German [d] changed into voiceless [t] , e.g. Daube (‘pidgeon, standard Taube),

- [g] in suffix -ig changed into [ś], e.g. diśdiś (‘brave’, standard tüchtig),

- Central High German [st] changed in final position and in the middle of a word in [szd], e.g. geszdǝr

(‘yesterday’, standard Gestern), Durschd (`thirst’, standard. Durst), - in two-syllable words n disappeared in the final position (except the words z [g] in the middle, e.g. Regen ‘rain’), np. Oowǝ/Oofǝ (‘oven’, standard Ofen) - the double n is maintained in one-syllable words, e.g. Man (‘man’, standard Mann).

Morphology

- genitive basically disappeared - it is formed only from anthroponym, e.g. Maajǝrsch Kaarl (‘Karl, son of Mayer’), and also used in some fixed phrases, e.g. daags (standard Tags ‘ in daylight’), Gods Wilǝ (standard Gottes Willen ‘God’s love),

- forms in Nominative, Accusative and Dative became the same - the only difference is visible between plural and singular forms, which is presented below in the table showing inflection of the word Hund (‘dog’):

l.p. szw.-gal. l.p. stdn. l.mn. szw.-gal. l.mn. stdn. M. där/dǝr Hund der Hund di Hunǝ die Hunde C. dem/dǝm Hund dem Hund(e) dǝ Hunǝ den Hunden B. dǝ Hund den Hund di Hunǝ die Hunde - past simple disappeared (Präteritum/Mitvergangenheit).

The dialect from Łódź

Edmund Effenberger (2010: 34 Effenberger 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Effenberger 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Effenberger, Edmund 2010. Das Lodzerdeutsch. Mönchengladbach: Archiv der Deutschen aus Mittelpolen und Wolhynien.

), comparing the Łódź dialect to the standard German language, distinguished a series of phonetic phenomena. He did not, however, analysed which mechanisms contribute to their emerging. Among the examples are:

), comparing the Łódź dialect to the standard German language, distinguished a series of phonetic phenomena. He did not, however, analysed which mechanisms contribute to their emerging. Among the examples are:- a>e, e.g. manch>mench (`some‘)

- au>oo, e.g. verkaufen>vekoofen (`sell‘)

- au>u, e.g. auf>uff (‘on‘)

- devoicing [b]at the beginning of a word, e.g. Bauer>Pauer (‘peasent, farmer’)

- b>w, e.g. Kiebitz>Kiewitz (`peewit’)

- e>ä, e.g. sehen sie>sähnse (`they see‘)

- ei>ee, e.g. ein>een (‘one’)

- eu>ei, e.g. neu>nei (`new‘)

- eu>ee, e.g. scheuchen>scheechen (‘scare away’)

- ig>ich, e.g. barfüssig>barfissich (`barefoot‘)

- ü>ie, i, e.g. Füße>Fiesse~Fisse (`feet‘)

- word stress shift, e.g. Salát>Sálat, Petroléum> Petróleum (`lettuce‘, `petroleum‘)

ISO Code

ISO-639-3: German - deu,

Palatine - pfl,

Swabian - swb.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - ger;

historical variations are: gmh – Middle High German, goh – Old High German;

other German languages - gem.

SIL (13 ed. The Ethnologue): ger; at present The Ethnologue: deu.

Palatine - pfl,

Swabian - swb.

The Library of Congress MARC 21 standard - ger;

historical variations are: gmh – Middle High German, goh – Old High German;

other German languages - gem.

SIL (13 ed. The Ethnologue): ger; at present The Ethnologue: deu.

- przyp01

- Żebrowska 2002

- Lewis i in. 2013

- Mitzka 1959

- Kargel 1941

- Krämer 1979

- Czoernig 1857

- Mitzka 1943

- Weigelt 2010

- Breyer 2006

- Urban 2004

- Sprothen 2007

- Paul 1962

- Paul 1965

- Finckh 1931

- Christmann 1931a

- Kollauer 1931

- Brubaker 1998

- Paradowska a

- Paradowska b

- Koerth 1929

- Pauls i Krahn 1956

- Bender i Bergmann 1987

- Kawski 2010

- Żebrowska 2004

- Krämer 1931

- Effenberger 2010

- Beck-Vellhorn i Scharlach 1936a

- Haeufler 1846

- Kossmann 1935

- Kłańska 1991

- Karasek-Langer i Strzygowski 1932

- Karasek-Langer Alfred i Elfriede Strzygowski 1938

- Goetze 1922

- Schmit 1942

- Beck-Vellhorn i Scharlach 1936b

- Müller 1962

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Baner reklamowy

- Odsetek Niemców w gminach

- Odsetek Niemców w-m

- Gwary niemieckie w Polsce wg Maurmanna

- PGR-Arbeiter

- książka Göttnera

- Urna ze swastykami pochodząca z Łódzkiego

- Izoglosy w Prusach

- Rozmieszczenie Niemców w Polsce środkowej IIRP

- Lodzer Zeitung

- Galicyjskie dziewczęta przy pracy

- Współcześni Bambrzy

- Izoglosy w gwarach Galicji

- Tekst szryftem gotyckim

- Zapożyczenia polskie i ukraińskie

- Schemat maselnicy

- Zapożyczenia w gwarze łódzkiej

- Podania

- Analiza Krämera

- Pieśń z Woli-Oblasznicy

- Huasnpolka – szwabski taniec z Machlińca

- Granica dialektów w płn. Polsce

- tabela do gwar Galicji

- Milch w Biskupiej Górce