Hałcnovian and Bielsko-Biała enclave

Introduction

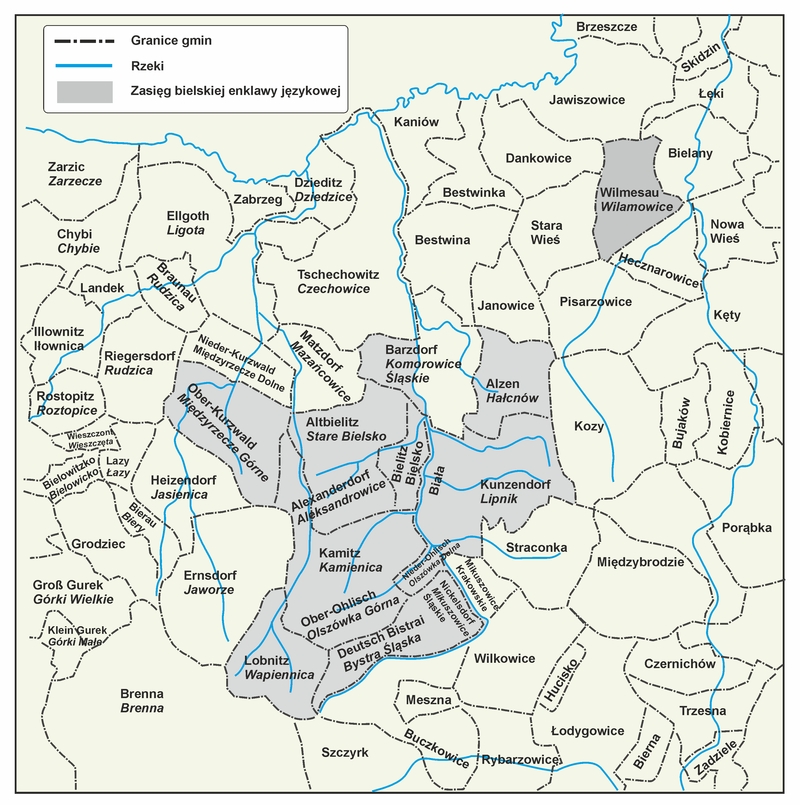

German scholars employed the term "Bielsko-Biała language enclave" (Bielitz-Białaer Sprachinsel) to describe the several towns and villages adjacent to (then) two towns in Cieszyn Silesia and Lesser Poland - Bielsko and Biała. Up until the times of the II World War, the majority populations of those two towns were German-speaking. According to these German scholars, apart from Bielsko, the language enclave encompassed the following:• Międzyrzecze Górne (Ober-Kurzwald),

• Komorowice Śląskie (Batzdorf),

• Kamienica (Kamitz),

• Wapienica (Lobnitz),

• Bystra Śląska (Deutsch-Bistrai),

• Aleksandrowice (Alexanderfeld),

• Mikuszowice (Nickelsdorf),

• Olszówka Górna (Ober-Ohlish),

• Olszówka Dolna (Nieder-Ohlish) oraz

• Stare Bielsko (Altbielitz).

On the other side of the river Biała and near the town of the same name the villages:

• Lipnik (Kunzendorf),

• Hałcnów (Alzen),

• Wilamowice (Wilmesau).

were also considered to comprise the language enclave.

The inhabitants of Wilamowice, however, do not consider themselves German. Taking this attitude into account while also accounting for the linguistic similarities between Wilamowicean and other dialects spoken in the aforementioned towns and villages, this work will use the term: The Bielsko-Biała German language enclave and Wilamowice. Depending on the given context, the place names of the given localities will be provided either in Polish or in standard German.

Name

Linguonyms

Endolinguonyms

Most of those who inhabited the towns and villages included in the, so called, Bielsko-Biała language enclave was probably aware that the language variety they speak was different from the standard (Hochdeutsh) version of the German language. Often they would describe their own variety as "rural". In Bielsko and Biała the term pauerisch(e) (Bock 1916a: 220 Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment /

Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment / Bock Friedrich 1916b. Der Liega-Jirg. Gedicht in der Bielitzer Mundart. Bielitz: Friedrich Bock. [przedruk w: Wagner 1936: 222-230].

) was used to describe it, whereas in Hałcnów it was päuersch. Jacob Bukowski, an educated medical doctor and a poet writing in the Biała dialect, put his language in a different light: In one of his poems he wrote: "Ens're alde Hajmetsproch", which can be translated as "Our old mothertongue" (1860: 1

) was used to describe it, whereas in Hałcnów it was päuersch. Jacob Bukowski, an educated medical doctor and a poet writing in the Biała dialect, put his language in a different light: In one of his poems he wrote: "Ens're alde Hajmetsproch", which can be translated as "Our old mothertongue" (1860: 1 Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment /

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment / Bukowski, Jacob 1860. Gedichte in der Mundart der deutschen schlesisch-galizischen Gränzbewohner resp. von Bielitz-Biala. Bielitz: Zamarski. [przedruk w: Wagner 1935: 1-190].

).

). Only in two of all discussed cases have such native names to call their own language variety developed. The people of Hałcnów named their variety aljzjnerisch or aljznerisch, the people of Wilamowice - Wymysiöeryś. This can be result of the peripheral location of both villages and, most importantly, the higher than anywhere else linguistic diversity. While it might be possible to form the language name based on the respective place name (e.g. Old Bielsko - starobielski - aldabeltzersich), such forms are not attested any known sources.

Exolinguonyms

It was primarily German scholars that were attracted to the dialects of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave. In their work they have mainly used the standard German language, Hochdeutsh.The subjects of their inquiry were, thus, named:- die deutsch-schlesiche Mundart (the German-Silesian dialect - Wagner 1935: 302

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc. )

) - Mundart der deutschen schlesisch-galizischen Gränzbewohner (the German dialect of the Silesian-Galician borderland - Bukowski 1860

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment /

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment /

Bukowski, Jacob 1860. Gedichte in der Mundart der deutschen schlesisch-galizischen Gränzbewohner resp. von Bielitz-Biala. Bielitz: Zamarski. [przedruk w: Wagner 1935: 1-190]. )

) - die ostschlesisch-galizischen deutschen Mundart ( the East Silesian-Galician German dialect - Bock 1916b: 214

Bock 1916b / komentarz/comment /

Bock 1916b / komentarz/comment /

Bock Friedrich 1916b. Der Liega-Jirg. Gedicht in der Bielitzer Mundart. Bielitz: Friedrich Bock. [przedruk w: Wagner 1936: 222-230]. )

) - Bielitzer Mundart (Bielsko dialect - Bock 1916b: 214

Bock 1916b / komentarz/comment /

Bock 1916b / komentarz/comment /

Bock Friedrich 1916b. Der Liega-Jirg. Gedicht in der Bielitzer Mundart. Bielitz: Friedrich Bock. [przedruk w: Wagner 1936: 222-230]. )

) - Bielitzer Mundarten (Bielsko dialects - Wagner 1935: XVI

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc. )

) - Mundart der Bielitzer Sprachinsel (the dialect of the Bielsko language enclave - Weiser 1937

Weiser 1937 / komentarz/comment /

Weiser 1937 / komentarz/comment /

Weiser, Franz 1937. „Zur Mundart der Bielitzer Sprachinsel“, w: Schlesisches Jahrbuch 9: 121-128. )

) - Dialekt der Deutschen im vormaligen Österreichisch-Schlesien (the dialect of the German people living in the former Austrian Silesia - Waniek 1897

Waniek 1897 / komentarz/comment /

Waniek 1897 / komentarz/comment /

Waniek, Gustav 1897. „Dialekt der Deutschen im vormaligen Oesterreichisch-Schlesien“, w: Die Österreich-Ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild. Wien. [przedruk w: Wagner 1935: 202-213]. ).

).

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

) he employed the term Baalaer Dialekt (the Biała dialect) Simpler terms, such as stadbielitzerisch (the urban Bielsko dialect - Bock 1916a: 220

) he employed the term Baalaer Dialekt (the Biała dialect) Simpler terms, such as stadbielitzerisch (the urban Bielsko dialect - Bock 1916a: 220 Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment /

Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment / Bock Friedrich 1916b. Der Liega-Jirg. Gedicht in der Bielitzer Mundart. Bielitz: Friedrich Bock. [przedruk w: Wagner 1936: 222-230].

) rarely can encountered . On the other hand, the term alznerisch (Halcnów language) which refers to the Hałcnów language variety is consistently used in the works of Karl Olma (e.g. Olma 1983

) rarely can encountered . On the other hand, the term alznerisch (Halcnów language) which refers to the Hałcnów language variety is consistently used in the works of Karl Olma (e.g. Olma 1983 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

).

).In Polish, the names of the dialects are created by forming an adjective on the basis of the given place name, e.g. starobielski (Old Bielsko), hałcnowski (Hałcnów), lipnicki (Lipnik), kamienicki (Kamienica)

The Silesian version of wikipedia.org describes the Bielsko dialect as bjelsko godko.

History and geopolitics

Location

The term "Bielsko-Biała language enclave" is a relatively new one - it was created on the turn of the 19th and XX centuries. It has been employed to describe the various German dialects that were spoken in the towns of Bielsko and Biała, and the villages located around them. Both the ethnic and linguistic environments change over them, it is no wonder, thus, that the extent of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave would be altered as well.Among many attempts to determine the borders of the enclave one may list the scholar Gerhard Wurbs (1981: 84, 85

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). He enumerated three types of villages/town. The first group comprises of those localities that maintained their German nature up until the year 1945:

). He enumerated three types of villages/town. The first group comprises of those localities that maintained their German nature up until the year 1945:- Bielsko (Bielitz)

- Biała (Biala)

- Lipnik (Kunzendorf)

- Hałcnów (Alzen)

- Wilamowice (Wilmesau)

- Komorowice Śląskie (Batzdorf)

- Międzyrzecze Górne (Ober Kurzwald)

- Wapienica (Lobnitz)

- Stare Bielsko (Altbielitz)

- Aleksandrowice (Alexanderfeld)

- Kamienica (Kamitz)

- Olszówka (Ohlisch)

- Bystra (Bistrai)

- Mikuszowice Śląskie (Nickelsdorf)

- Jasienica (Heinzendorf)

- Jaworze (Ernsdorf)

- Bystra Krakowska (Bistrai-Süd)

- Mikuszowice Krakowskie (Mikuschowitz)

- Straconka (Dresseldorf)

- Kozy (Seibersdorf)

- Pisarzowice (Schreibersdorf)

- Stara Wieś (Altdorf)

- Komorowice Krakowskie (Mückendorf)

- Mazańcowice (Matzdorf)

- Landek (Landeck)

- Bronów (Braunau)

- Wilkowice (Wilkowitz)

- Łodygowice (Lodygowitz)

- Kęty (Liebenwerde, też Liewerdt)

- Nowa Wieś (Neudorf)

- Nidek (Nydek)

- Dankowice (Denkendorf)

Polak 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2012 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy 2012. Bielsko-Biała w zwierciadle czasu. Wspomnienia mieszkańców z lat 1900-1945. Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego.

). The inhabitants of Wilamowice, on the other hand, did not consider their language to be a dialect of German (cf e.g. Filip 2005

). The inhabitants of Wilamowice, on the other hand, did not consider their language to be a dialect of German (cf e.g. Filip 2005 Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment /

Filip 2005 / komentarz/comment / Filip, Elżbieta Teresa 2005. „Flamandowie z Wilamowic? [Stan badań]”, Bielsko-Bialskie Studia Muzealne IV: 146-198.

, Wicherkiewicz 2001

, Wicherkiewicz 2001 Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2001 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2001. „Piśmiennictwo w etnolekcie wilamowskim”, w: Barciak 2001: 520-538.

, Wicherkiewicz 2003

, Wicherkiewicz 2003 Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment /

Wicherkiewicz 2003 / komentarz/comment / Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz 2003.The Making of a Language. The Case of the Idiom of Wilamowice, Southern Poland. Berlin-New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

). Moreover, describing Straconka as a former German village does not bear scrutiny considering source materials. On the other hand, Polish scholars, and among them even those who adopted a nationalist bias to their works, suggest that some of the villages adjacent to Bielsko and Biała share their German origin. Józef Latosiński, a historian-hobbyist, author of Monografia Miasteczka Wilamowic, wrote that:

). Moreover, describing Straconka as a former German village does not bear scrutiny considering source materials. On the other hand, Polish scholars, and among them even those who adopted a nationalist bias to their works, suggest that some of the villages adjacent to Bielsko and Biała share their German origin. Józef Latosiński, a historian-hobbyist, author of Monografia Miasteczka Wilamowic, wrote that: Apart from Wilamowice and Stara Wieś, the following German settlements were erected here on Oświęcim soil: Pisarzowice (Schreibersdorf), Kęty (Liebenwerde), Kozy (Seubersdorf) , Hałcnów (Alzen), Lipnik (Kunzendorf), Komorowice (Bertholdsdorf), Łodygowice (Ludwigsdorf), Inwałd (Hinwald), Barwałd (Bärenwald) and others.Prior to 1918, many inhabitants of the discussed territories worked in the country to which they officially belonged to - the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most of them, thus, had to quickly adapt to their new linguistic environment.

In the aftermath of the repartiation of German people after the II World War, the Bielsko-Biała language enclave ceased to be a concentrated aggregation of a German-speaking population.

Probably by now Bielitzer Mundart is known but to a few people who were resettled from the vicinity of Bielsko and Biała after the II World War to today's Germany and Austria.

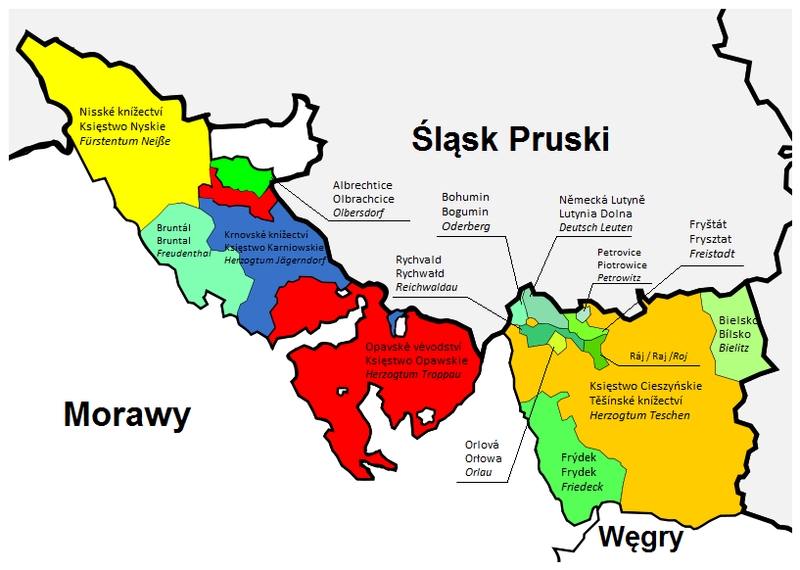

The Bielsko-Biała language enclave and the pre-war (↑) and present (↓) administrative structure - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz

History and origins

The border between Silesia and Lesser Poland

The territories of and around today's Bielsko-Biała for a very long time were virtually uninhabited. Even in the earliest times when Poland was still in the process of forming an independent country, this area was barren and constituted a border between two Slavic tribes: the Golensizi in the West and Vistulans in the East (Chorąży and Chorąży 2010b: 119 Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010b. „Początki Bielska”, w: Panic 2010:141-159.

). In the 11th century two gords (or Slavic burgwalls) were established near this place, Cieszyn and Oświęcim, which soon became two administrative centres known as castellanies. The river Białka separated these two centres, as it does presently, separating Bielsko-Biała into two parts by flowing straight through it. This border was adopted by the Church administration as well. The territory West from the river Białka became a part of the diocese of Wrocław while the territory on the Eastern side of the river would fall to the Bishop of Cracow. This division was surprisingly lasting. it ended only in the 20th century, perhaps with the exception of one period that will be discussed later on. In the consciousness of present inhabitants of the area, however, this divide is still very much alive.

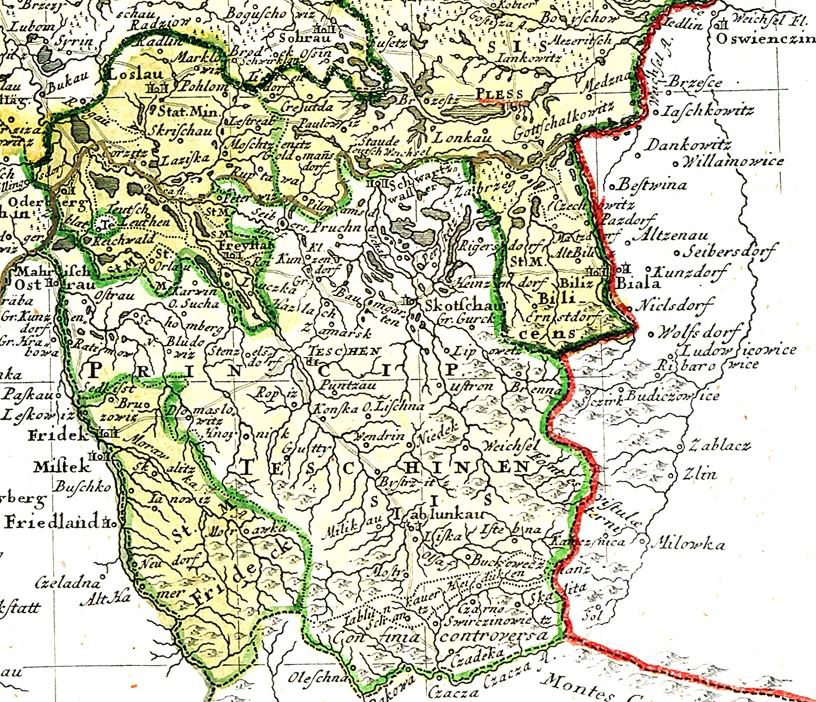

). In the 11th century two gords (or Slavic burgwalls) were established near this place, Cieszyn and Oświęcim, which soon became two administrative centres known as castellanies. The river Białka separated these two centres, as it does presently, separating Bielsko-Biała into two parts by flowing straight through it. This border was adopted by the Church administration as well. The territory West from the river Białka became a part of the diocese of Wrocław while the territory on the Eastern side of the river would fall to the Bishop of Cracow. This division was surprisingly lasting. it ended only in the 20th century, perhaps with the exception of one period that will be discussed later on. In the consciousness of present inhabitants of the area, however, this divide is still very much alive. The Oświęcim and Cieszyn regions in the Middle Ages

During Poland's fragmentation period, in 1179 a new ruler took control over Oświęcim and its surroundings which constituted the Eastern part of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave. It was Mieszko I Tanglefoot who received the castellanies of Oświęcim and Bytom from Casimir II the Just following Mieszko's son baptism. This way Mieszko became the ruler of vast territories encompassing the lands of Racibórz, Oświęcim, Opole and Cieszyn (Putek 1938: 1 Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

). The whole of this area would later constitute a part of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave for nearly 140 years but at that time it was a separate and distinct administrative unit which, however, experienced fragmentation because of the last will's of their rulers. In 1290 the Duchy of Cieszyn emerged. It comprised also of the lands of Oświęcim, Zator and Chrzanów. Mieszko I of Cieszyn became its ruler. After his death in 1316 further fragmentations occurred and a separate Duchy of Oświęcim was created. The whole of the territory located East from the river Bialka was incorporated into the new Duchy (Putek 1938: 2

). The whole of this area would later constitute a part of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave for nearly 140 years but at that time it was a separate and distinct administrative unit which, however, experienced fragmentation because of the last will's of their rulers. In 1290 the Duchy of Cieszyn emerged. It comprised also of the lands of Oświęcim, Zator and Chrzanów. Mieszko I of Cieszyn became its ruler. After his death in 1316 further fragmentations occurred and a separate Duchy of Oświęcim was created. The whole of the territory located East from the river Bialka was incorporated into the new Duchy (Putek 1938: 2 Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

; Wurbs 1981:11

; Wurbs 1981:11 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

).

).

Duchy of Cieszyn in 1746, see: http://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:Principatus_Teschinenis_Superiorem_Silesiam_AD1746.jpg

As time passed the ties between the Piast dynasty in Cieszyn and Oświęcim, and the Polish senior ruler in Cracow loosened. Some of the princess attempted to maintain their political independence. Others, however, paid homepage to Czech kings and became their vassals. These ties were finally severed in 1335 with the Treaty of Trentschin. Under this treaty, Casimir III The Great abandoned his claims to Silesian Duchies, the Duchies of Oświęcim and Cieszyn included. The former, along with Biała and adjacent villages returned to Poland in 1453 while the territories between the rivers Olza and Białka which belonged to the Duchy of Cieszyn (with Bielsko) were officially incorporated into Poland only in the year 1920.

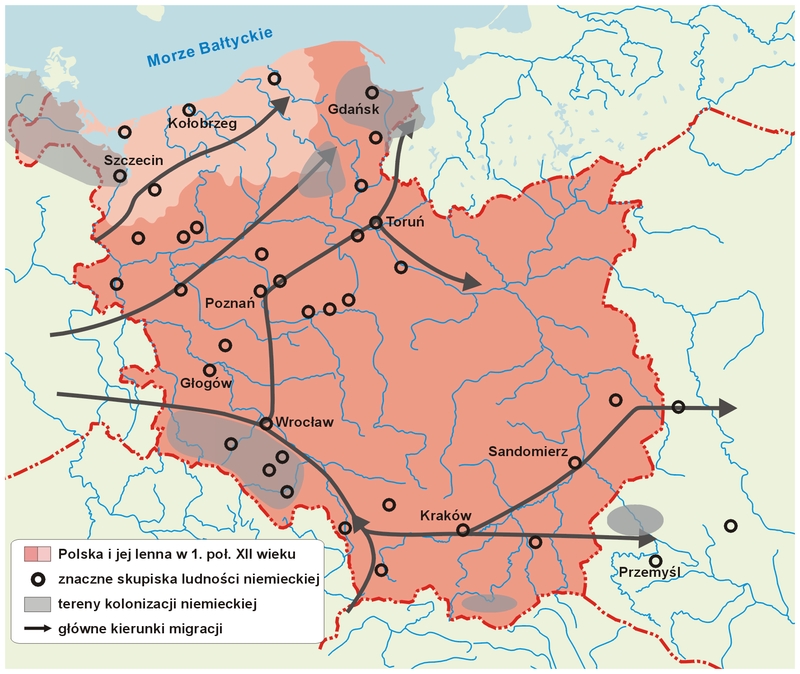

Colonisation processes - the emergence of towns

The fragmentation of bigger duchies into smaller ones had a significant effect on language diversity. As the territories ruled by various sovereigns became smaller, so did the income. The only way to increase it was to invite colonists to previously uninhabited lands. The tribute (paid after the initial tax-free period - wolnizna) allowed to fill the coffers of the given prince (Putek 1938: 25 Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

). It would seem only natural to bring settlers from neighbouring parts of Poland. However, the already thin population numbers were even more so diminished by Tatar raids. That is why the Piast Silesian princes and the courtiers, knights and officials they provided for invited settlers from overpopulated German-speaking areas.

). It would seem only natural to bring settlers from neighbouring parts of Poland. However, the already thin population numbers were even more so diminished by Tatar raids. That is why the Piast Silesian princes and the courtiers, knights and officials they provided for invited settlers from overpopulated German-speaking areas.

German colonization in Middle Ages - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz

Before this process began, there had been only one settlement point for emigrants on the discussed territory. Its existence can be proved mainly by archeological works (Chorąży and Chorąży 2010b

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010b. „Początki Bielska”, w: Panic 2010:141-159.

). It was a (probably) Slavic hill fort located in today's Stare Bielsko. The hill fort was established at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries and was inhabited for approximately 100 years.

). It was a (probably) Slavic hill fort located in today's Stare Bielsko. The hill fort was established at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries and was inhabited for approximately 100 years.

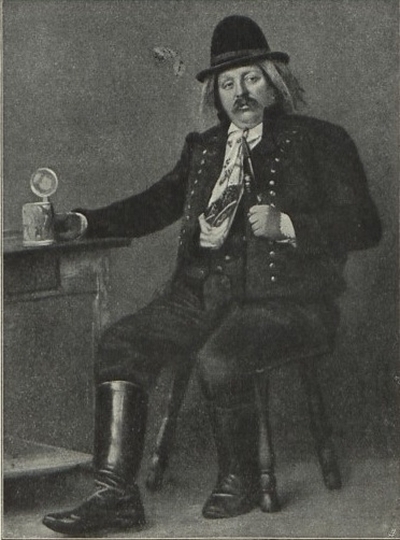

Local population of Stare Bielsko in regional dresses, (See: Wagner 1935: 2

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

)

)

Couple from Hałcnów in their wedding costumes (interwar). Private source

A much more extensive colonisation process began in the late second half of the 13th century. It was then that Bielsko, Komorowice and Lipnik were created. Moreover, at the beginning of the 14th century Mikuszowice, Kamienica, Międzyrzecze and Bertoldowice which later became a part of Komorowice, joined the already established villages. (Chorąży and Chorąży 2010c: 205, 211

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010c. „Zaplecze osadnicze Bielska”, w: Panic 2010: 205-222.

). In the second half of the 13th century Wilhelmsdorf or Antiquo Wilamowicz (present-day Stara Wieś) was founded. Later on, prior to 1325, however, a number of inhabitants of Stara Wieś moved a few kilometres and settled Wilamowice (Barciak 2001: 82, 85

). In the second half of the 13th century Wilhelmsdorf or Antiquo Wilamowicz (present-day Stara Wieś) was founded. Later on, prior to 1325, however, a number of inhabitants of Stara Wieś moved a few kilometres and settled Wilamowice (Barciak 2001: 82, 85 Barciak 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Barciak 2001 / komentarz/comment / Barciak, Antorni (red.) 2001. Wilamowice. Przyroda, historia, język, kultura, oraz społeczeństwo miasta i gminy. Wilamowice: Urząd Gminy.

).

).This is how the first colonisation wave ended. Later localities were created only after a 100 years. One of the reasons behind it was the Black Death pandemic which decimated the population of Western Europe. The first village to be established after such a long break was Hałcnów. The exact spot for this settlement was determined in 1404 (Chorąży and Chorąży 2010c: 213

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010c. „Zaplecze osadnicze Bielska”, w: Panic 2010: 205-222.

). Further villages were founded much later. In 1561 Olszówka Górna and Olszówka Dolna were set up (Panic 2010: 350

). Further villages were founded much later. In 1561 Olszówka Górna and Olszówka Dolna were set up (Panic 2010: 350 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). Interestingly, the later settlement was established by the town of Bielsko and was treated as its property. Prior to 1572 Bystra was established (Wurbs 1981: 22

). Interestingly, the later settlement was established by the town of Bielsko and was treated as its property. Prior to 1572 Bystra was established (Wurbs 1981: 22 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). The youngest village of the Bielsko-Biała German language enclave is Aleksandrowice/Alexandersfeld jest which can be dated to the 1750s (Panic 2010: 358

). The youngest village of the Bielsko-Biała German language enclave is Aleksandrowice/Alexandersfeld jest which can be dated to the 1750s (Panic 2010: 358 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

).

).The history of the Western part of the language enclave - the Middle Ages and Modernity

As it has been mentioned previously, Bielsko began to emerge by the end of the 13th century. This initially rural settlement slowly began to expand and develop into a town, and setting the town under German law between 1315 and 1327 may be considered the capstone of this process (Chorąży and Chorąży 2010b: 152 Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010b. „Początki Bielska”, w: Panic 2010:141-159.

). In the initial stages of the town's existence, it did not bear much importance to the Duchy of Cieszyn (Panic 2010: 137

). In the initial stages of the town's existence, it did not bear much importance to the Duchy of Cieszyn (Panic 2010: 137 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

) and it gave way to, e.g. Skoczów which was a couple of kilometres away. The situation changed following Bolesław I's new law enactment on the 8th of November 1424. The document regulated the administrative and legislative structures of the town (Panic 2010: 180

) and it gave way to, e.g. Skoczów which was a couple of kilometres away. The situation changed following Bolesław I's new law enactment on the 8th of November 1424. The document regulated the administrative and legislative structures of the town (Panic 2010: 180 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). Under the new law, craftsmen were obligated to join guilds (Wurbs 1981: 16

). Under the new law, craftsmen were obligated to join guilds (Wurbs 1981: 16 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

).

). In the Middle Ages Bielsko was recognized the as centre of a special economic area. Under this law privilege, inhabitants of settlement within a mile radius from Bielsko had no right to compete with the craftsmen from Bielsko. They were, however, recipients of farming products grown in Bielsko (Choraży and Chorąży 2010c: 205

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c / komentarz/comment /

Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c / komentarz/comment / Chorąży, Bożena i Bogusław Chorąży 2010c. „Zaplecze osadnicze Bielska”, w: Panic 2010: 205-222.

). This kind of division of roles strengthened Bielsko as a manufacturing centre. By the end of the 15h century, the Bielsko economic area was settled by over 2500 people, 1100 of which lived in the town itself.

). This kind of division of roles strengthened Bielsko as a manufacturing centre. By the end of the 15h century, the Bielsko economic area was settled by over 2500 people, 1100 of which lived in the town itself.The Cieszyn Piast dynasty, however, fell into financial problems by the 16h century. Warring with Turkish forces depleted the coffers of Wenceclaus III Adam. During the elections in 1573 he was a candidate for the position of King of Poland, yet, as it is now known, he was not raised to this dignity. Frederick Casimir of Cieszyn, Wenceslaus III's son, was renowned for his profligate lifestyle (Panic 2002: 27-28

Panic 2002 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2002 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi 2002. Poczet Piastów i Piastówien cieszyńskich. Cieszyn: Biuro Promocji i Informacji. Urząd Miejski.

). As a consequence, Bielsko and the villages in its vicinity were separated from the Duchy of Cieszyn and served as a collateral for princely loans. During this period, the rule over Bielsko was often transferred from one person to another. Finally, in 1583 the Bielsko region become an independent political unit, associated with the Duchy of Cieszyn only by the fact that it was within its territory (Panic 2010: 286

). As a consequence, Bielsko and the villages in its vicinity were separated from the Duchy of Cieszyn and served as a collateral for princely loans. During this period, the rule over Bielsko was often transferred from one person to another. Finally, in 1583 the Bielsko region become an independent political unit, associated with the Duchy of Cieszyn only by the fact that it was within its territory (Panic 2010: 286 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). It acquired the status of a state country and, thus, began to answer directly to the empire offices in Wrocław (Panic 2010: 285

). It acquired the status of a state country and, thus, began to answer directly to the empire offices in Wrocław (Panic 2010: 285 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). Bielsko was ruled and owned by the following houses: Schaffgotsh, Sunnegh, Solms and, since the second half of the 18th century, by the Sułkowski family (Panic 2010: 283-299

). Bielsko was ruled and owned by the following houses: Schaffgotsh, Sunnegh, Solms and, since the second half of the 18th century, by the Sułkowski family (Panic 2010: 283-299 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). In most cases, the rulers of Bielsko were protestant. In 1587 Adam Schaffgotsh enacted a privilege under which his subjects were offered religious freedom (Hanslik 1938: VII

). In most cases, the rulers of Bielsko were protestant. In 1587 Adam Schaffgotsh enacted a privilege under which his subjects were offered religious freedom (Hanslik 1938: VII Hanslik 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1938 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin 1938. „Über die Entstehung und Entwicklung von Bielitz-Biala. – Die Kulturformen der Bielitz-Bialaer deutschen Sprachinsel“ [teksty z 1903 i 1906 roku]. w: Wagner 1938.

).

).Throughout the long decades, the inhabitants of Bielsko and its surrounding settlements became victims of bad economy decisions made by the rulers of the Bielsko dominion. As it was often in a state of financial distress, the rules would levy high taxes which, ultimately, halted the economic development of the region. Another blow to Bielsko was the Thirty Years' War when it was sacked by Hungarian rebels. The result of the war was a hundred-year-long decline in demography and economy (Kuhn 1981: 40

Kuhn 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Kuhn 1981 / komentarz/comment / Kuhn, Walter 1981. „Geschichte der deutschen Sprachinsel Bielitz (Schlesien)“. Quellen und Darstellungen zur schlesischen Geschichte 21. Würzburg: Holzner.

).

).History of the Eastern part of the language enclave - the Middle Ages and Modernity

Since its founding in the Middle Ages, for a long time Lipnik (Kunzendorf). The settlement was the seat of a non-town starostwo, a crown land rules by an official. It was owned by various nobility families (Polak 2010: 26 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). The first mentions of Biała, however, can be found rather late - in 1564 (Wurbs 1981: 83

). The first mentions of Biała, however, can be found rather late - in 1564 (Wurbs 1981: 83 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

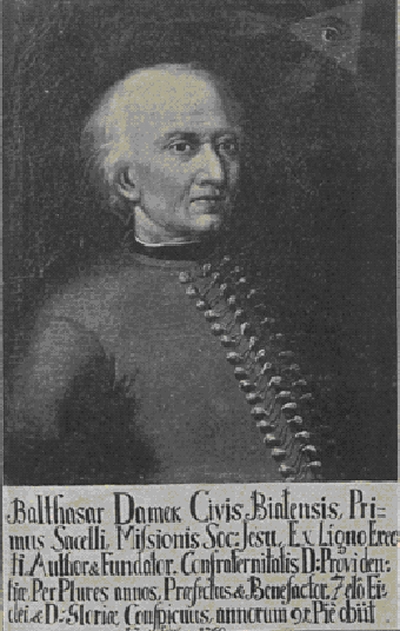

). At that time, the whole settlement comprised only of several buildings. Craftsmen from the neighbouring Bielsko were probably its first settlers. Following the end of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), fearing prosecution, many Silesian protestants settled in this border town. Since the artisans from Bielsko were not constrained by guild law they could provide cheaper products to the market. Such activities led to the expansion of the settlement which was granted town privileges under the decision of king Augustus II the Strong in 1723. Soon Biała became the property of the Crown (Polak 2010: 104

). At that time, the whole settlement comprised only of several buildings. Craftsmen from the neighbouring Bielsko were probably its first settlers. Following the end of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), fearing prosecution, many Silesian protestants settled in this border town. Since the artisans from Bielsko were not constrained by guild law they could provide cheaper products to the market. Such activities led to the expansion of the settlement which was granted town privileges under the decision of king Augustus II the Strong in 1723. Soon Biała became the property of the Crown (Polak 2010: 104 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). Its was mayor was Baltazar Damek, a patron of Catholicism, banker (or rather usurer) and the first arts patron in the town. Jerzy Polak suggests that he was a "Polonised Wilamowicean" (Polak 2010: 89, 104, 113, 115

). Its was mayor was Baltazar Damek, a patron of Catholicism, banker (or rather usurer) and the first arts patron in the town. Jerzy Polak suggests that he was a "Polonised Wilamowicean" (Polak 2010: 89, 104, 113, 115 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

). As a result of the First Partition of Poland in 1772, the territory of the Duchy of Oświęcim was incorporated into Austria. Initially, the Duchy did not constitute a part of Galicia.

). As a result of the First Partition of Poland in 1772, the territory of the Duchy of Oświęcim was incorporated into Austria. Initially, the Duchy did not constitute a part of Galicia.

Baltazar Damek (see: Hanslik 1908: 97

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin, 1908. Biala, eine deutsche Stadt in Galizien. Wien-Teschen-Leipzig.

)

)Industry development

Drapery in Bielsko was first mentioned in 1543 (Wurbs 1981: 18 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Since then this particular branch of industry was growing more and more important for the economy of Bielsko, Biała and their surroundings. After all, there were 271 drapers in Bielsko in 1734 (Wurbs 1981: 24

). Since then this particular branch of industry was growing more and more important for the economy of Bielsko, Biała and their surroundings. After all, there were 271 drapers in Bielsko in 1734 (Wurbs 1981: 24 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). The first cloth factory in Biała was founded in 1766, "Nostek and Meznarowski" (Wurbs 1981: 27

). The first cloth factory in Biała was founded in 1766, "Nostek and Meznarowski" (Wurbs 1981: 27 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). These manufacturing plants would soon began to displace individual drapers from the market. The industrial revolution only accelerated this process as the 19th century saw the construction of the first manufacturing machines which simplified the production of cloth. By 1872 there were 31 drapery factories, 3 spinning mills, 11 dyers and 9 cloth finishing factories. The Bielsko industrial area possessed 2570 handlooms and 487 electrical looms (Wurbs 1981: 39

). These manufacturing plants would soon began to displace individual drapers from the market. The industrial revolution only accelerated this process as the 19th century saw the construction of the first manufacturing machines which simplified the production of cloth. By 1872 there were 31 drapery factories, 3 spinning mills, 11 dyers and 9 cloth finishing factories. The Bielsko industrial area possessed 2570 handlooms and 487 electrical looms (Wurbs 1981: 39 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). By 1902 20% of all the factories connected with the cloth industry in the Austro-Hungarian Empire were located, in fact, in region of Bielsko (Wurbs 1981: 42

). By 1902 20% of all the factories connected with the cloth industry in the Austro-Hungarian Empire were located, in fact, in region of Bielsko (Wurbs 1981: 42 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Thousands of people from Austria, Moravia, Prussian Silesia and Galicia were, thus, pulled in to Bielsko, Biała and other localities whose economies thrived. By the end of the 19th century immigrants constituted half of the population of Bielsko (Spyra 2010: 139

). Thousands of people from Austria, Moravia, Prussian Silesia and Galicia were, thus, pulled in to Bielsko, Biała and other localities whose economies thrived. By the end of the 19th century immigrants constituted half of the population of Bielsko (Spyra 2010: 139 Spyra 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Spyra 2010 / komentarz/comment / Spyra, Janusz 2010. ”Przeobrażenia struktur społecznych i narodowościowych w Bielsku w drugiej połowie XIX i początkach XX wieku, w: Spyra i Kenig 2010: 137-157.

). In Biała this ratio was even bigger. Out of the total 5190 people living in Biała in 1890 only 2432 were considered to be "natives" (Polak 2010: 381

). In Biała this ratio was even bigger. Out of the total 5190 people living in Biała in 1890 only 2432 were considered to be "natives" (Polak 2010: 381 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

).

).

J. Vogt's factory (see: Hanslik 1908: 189

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin, 1908. Biala, eine deutsche Stadt in Galizien. Wien-Teschen-Leipzig.

)

)

Train station in Bielsko (see: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bielsko-Bia%C5%82a_G%C5%82%C3%B3wna_003.JPG)

Bielsko of that period was a rich town. The best Vienna architects designed the town's representational building and an electric tramway was founded quicker than it was done in Vienna or Warsaw (Wurbs 1981: 40

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Although Biała was poorer than Bielsko it still stood out from the other towns of Galicia. It differed not only in its levels of employment (Hanslik 1908: 178

). Although Biała was poorer than Bielsko it still stood out from the other towns of Galicia. It differed not only in its levels of employment (Hanslik 1908: 178 Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin, 1908. Biala, eine deutsche Stadt in Galizien. Wien-Teschen-Leipzig.

) but also enjoyed a higher level of literacy than anywhere else (Hanslik 1908: 235

) but also enjoyed a higher level of literacy than anywhere else (Hanslik 1908: 235 Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin, 1908. Biala, eine deutsche Stadt in Galizien. Wien-Teschen-Leipzig.

).

).

Austrian Silesia - map ed.: Jacek Cieślewicz.

After the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the territory of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave became a part of Poland. The area located East from the river Bialka was incorporated into the Kraków district (voivodeship). A plebiscite was to be organized for the former Austrian Silesia but, in the end, it did not eventuate. Bielsko and its surroundings joined Poland in 1920, more specifically - to the autonomic Silesian voivodeship. This new order did not last long, however. In 1939 Nazi Germany began the II World War. With its end in 1945, the communist took control over Poland and they felt that the German-speaking population should assume ultimate and collective responsibility. And hence, both those who actively supported Hitler and those who had nothing to do at all with any form of totalitarian rule were forced to leave their homes and resettle in Germany in Austria.

Myths of origin

It is difficult to indicate any concrete piece of information in German scholarly works pertaining to the Bielsko-Biała language enclave on where did this enclave originate from. The colonisation of new territories seems to be the most important fact in their works. The scant amount of information that exists (Wagner 1935: 193 Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

) is not enough to recognize it as mythology - regardless of the definitions that associated with the term. If we are to define mythology not as a collection of false beliefs but as a tale on the origins of a given community, and one that influences the nature of said community, then, clearly, it is possible to recognize the beliefs the people of Wilamowice and Hałcnów possess as mythology.

) is not enough to recognize it as mythology - regardless of the definitions that associated with the term. If we are to define mythology not as a collection of false beliefs but as a tale on the origins of a given community, and one that influences the nature of said community, then, clearly, it is possible to recognize the beliefs the people of Wilamowice and Hałcnów possess as mythology.Hałcnów

For a long time it was sufficient for the inhabitants of Hałcnów to say that their ancestors came from Germany (Olma 1983: 8 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

). Scholars (Walther Kuhn, Erwin Hanslik) whose works Karl Olma referred to (1983: 7

). Scholars (Walther Kuhn, Erwin Hanslik) whose works Karl Olma referred to (1983: 7 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

) and who were researching the history of Bielsko and its surroundings noticed that there were several villages named Alzen and Alzenau. Based on this fact it may be possible to conclude that all of these localities were founded by a group of people whose ancestors came from the same point of origin. This point in the long chain of towns and villages in Germany, Silesia, Biała and Spisz was thought to be Alzenau in Lower Franconia. The aforementioned historians regarded this theory with a degree of skepticism as until the 15h century, the Franconian town of Alzenau was named, in fact, Wilmundsheim (Olma 1983: 7-9

) and who were researching the history of Bielsko and its surroundings noticed that there were several villages named Alzen and Alzenau. Based on this fact it may be possible to conclude that all of these localities were founded by a group of people whose ancestors came from the same point of origin. This point in the long chain of towns and villages in Germany, Silesia, Biała and Spisz was thought to be Alzenau in Lower Franconia. The aforementioned historians regarded this theory with a degree of skepticism as until the 15h century, the Franconian town of Alzenau was named, in fact, Wilmundsheim (Olma 1983: 7-9 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

). Nonetheless, in 1958 Alzenau took patronage over the village of Hałcnów who were forced to leave their homeland after the war. The following sentence was written in the document confirming the provision of the patronage: "a perfect bridge has been erected to connect their little homeland with the homeland of their fathers" (Olma 1983: 189

). Nonetheless, in 1958 Alzenau took patronage over the village of Hałcnów who were forced to leave their homeland after the war. The following sentence was written in the document confirming the provision of the patronage: "a perfect bridge has been erected to connect their little homeland with the homeland of their fathers" (Olma 1983: 189 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

).

).

Andreas Olma, a local of Hałcnów, in his regional dress (see: Hanslik 1908: 38

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment /

Hanslik 1908 / komentarz/comment / Hanslik, Erwin, 1908. Biala, eine deutsche Stadt in Galizien. Wien-Teschen-Leipzig.

)

)

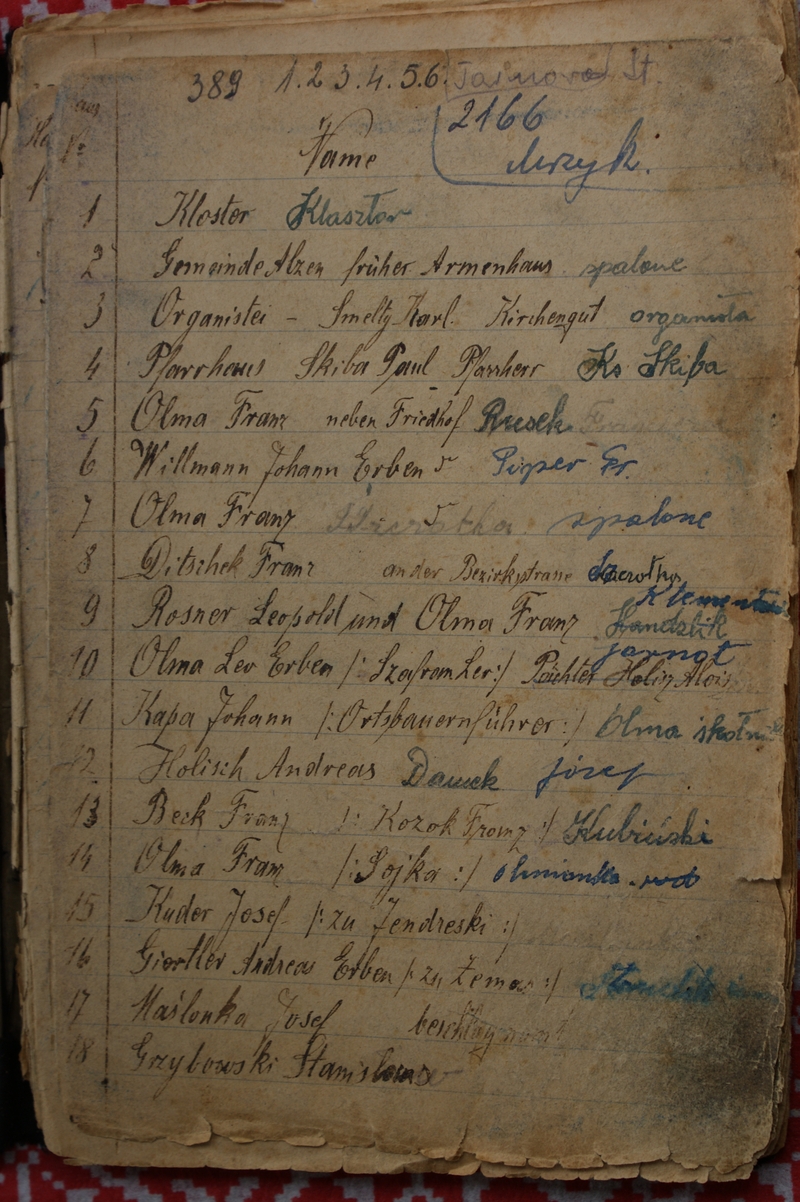

List of inhabitants of Hałcnów/Alzen (names and house numbers), compiled during the WWII (1943/1944). Private source

50 years later, the anniversary celebrations in Alzenau were covered by the local media (cf. http://www.main-netz.de/nachrichten/region/alzenau/alzenau-kurz/art3979,369464). The town's official webpage almost directly cited the sentence suggesting the existence of a bridge between Hałcnów and Alzenau (http://www.alzenau.de/pressedienst/?id=564). This testifies to the firm belief that the people of Hałcnów originated in Franconia, a fact which was also depicted in the poetry of Karl Olma:

| De jeschta Ajlzner Vu Alzenaa em Fränkischa met Bow an Kejnd, met Fad an Rejnd de Schles ganz düöchj wie Schnepf an Schtüöchj sän se gezünj, bi se verlüönj em Bajgsgehelz ne wäjt vu Beltz de Wanderlost... “Bränj eta Post zum Fjeschta hejn, do wir do bläjn!“ suojt Uma Hans zum „Welda Franz“ an trät ien Scheld, es Schmatzasbeld, zur greßta Ajchj: „Beschitz vir Pajchj, Krieg, Kranket, Nut, an helf zu Brut, Maria ens!“ A Scheßl Brens schtiäkt nom Gebat. Nocht keemt de At: Ficht fällt vir Ficht, der Pusch wjed licht; kaj Woch vergejt ans Diäfla schtejt... “Wie hajß wer, Vüöt, et enesen Üöt?“ frät Hettnesch Franz dan Uma Hans. “No wie denn? A ok Alzenaa!“ (Olma 1983: 4-5  Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.  ) ) |

Die ersten Alzner Von Alzenau im Fränkischen mit Weib und Kind, mit Pferd und Rind Schlesien ganz durch wie Schnepfe und Storch sind sie gezogen, bis sie verloren im Berggehölz nicht weit von Bielitz die Wanderlust... “Bring jetzt Nachricht zum Fürsten hin, daß wir hier bleiben!“ sagt Uma Hans zum „Wilden Franz“ und trägt ihren Schild, das Schmerzensbild, zur größten Eiche: „Beschütze vor Pech, Krieg, Krankheit, Not, und hilf zu Brot, Maria uns!“ Eine Schüssel Schafkäse stärkt nach dem Gebet. Dann kommt die Arbeit: Fichte fällt vor Fichte, der Wald war licht; keine Woche vergeht und das Dörflein steht... „Wie heißen wir, Vogt jetzt unseren Ort?“ fragt Hütten-Franz den Uma Hans. „Nun wie denn? Auch nur Alzenau!“ (Olma 1983: 4-5  Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.  ) ) |

The first peple of Hałcnów from Alzenau in Franconia, with an infant and with a child, with a horse and with a calf, through the whole of Silesia like a woodcock and a stork did travel until they lost their will to walk further in a mountain forest near Bielsko... "Bring this message to the prince that we're staying!" said Uma Hans to the "Wild Frantz" as he takes their shield, the image of our Lady of Sorrows, to the large oak: "Deliver us from bad luck, war, disease and poverty, and for bread we ask, oh Mary! A bowl of sheep's milk cheese strengthened them after their prayer. And that is when the work began: One spruce after another thinned out the forest; not a week has passed and a new village was built... "How do we call, now this place of ours?" asked Hettnesch Franz their chief, Uma Hans. "Now we will call it unmistakably Alzenaa!" (translated from B. C. Polish translation) |

ISO Code

no separate code for the Bielitz-Biala Sprachinsel or Hałcnovian

possible code: hlc

possible code: hlc

- Biogram

- Pieśń Olmy 1

- Pieśń Olmy 2

- Pieśn Olmy 3

- Pieśń Olmy 4

- Składanka pieśni Olmy

- Składanka pieśni Olmy 2

- Pieśn Olmy 5

- Modlitwa dziecięca

- Bajka o Wietrze Północnym i Słońcu

- Opowiadanie o weselu

- Opowiadanie o głównych zajęciach hałcnowian przed wojną

- Opowiadanie/rozmowa o kościele hałcnowskim

- Dialog o strojach hałcnowskich

- Rozmowa o hałcnowiankach

- Krótki wierszyk

- Dwa dowcipy hałcnowskie

- Opowiadanie o ostatnich tygodniach

- Pieśń Olmy w wykonaniu męskim

- Rozmowa o życiu dzieci przed wojną

- Rozmowa o Świętach Bożego Narodzenia

- Rozmowa o dzieciństwie

- Zdania Wenkera

- Żart o wilamowianach (video)

- Opowiadanie o zalotach

- Pieśń hałcnowska - wersja video

- Opowiadanie o odpuście

- Rozmowa o jedzeniu (video)

- Dokumenty hałcnowskie sprzed wieków

- Informatorzy

- Zbiór pieśni hałcnowskich

- Stroje hałcnowskie

- Rozmowa o wilamowianach (doświadczenia z dzieciństwa)

- Słowniczek polsko-hałcnowski

- Lista Swadesha

- Arkusz Wenkera

- Zasady zapisu

- Słowniczek bielski

- Schatzla, eta komma wir [tekst]

- Alzner Hymne [tekst]

- Rozmowa o wsi przed wojną

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia na KNG

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia na SNBHJ w Toruniu

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia w Kamieniu Śląskim

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia na OKH w Poznaniu

- Bock 1916b

- Weiser 1937

- Waniek 1897

- Olma 1983

- Polak 2012

- Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b

- Putek 1938

- Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c

- Panic 2010

- Panic 2002

- Hanslik 1938

- Kuhn 1981

- Polak 2010

- Hanslik 1908

- Meier & Meier 1979

- Zöllner 1988

- Chodera i Kubica 1984

- Urban 2001

- Janoszek i Zmełty 2004

- Mickler 1938

- Wagner 1937a

- Wagner 1937b

- Wagner 1938

- Gusinde 1911

- Spyra 2010

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- Wiadomości na temat zaimków hałcnowskich

- Odmiana wybranych czasowników hałcnowskich

- Wiadomości na temat rodzajników hałcnowskich

- Zasady transkrypcji nagrań hałcnowskich

- Skrócony opis fonetyki/fonologii hałcnowskiej

- osoby z Hałcnowa,Bielska,Białej zmarłe w Oświęcimi

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Mapa bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej

- Arkusz Wenkera z DiWA

- fotografia pary z Hałcnowa w Wilamowicach

- akt małżeństwa

- Dworzec kolejowy w Bielsku

- Księstwo cieszyńskie w roku 1746

- strona tytułowa Bukowski 1860

- Panorama Bielska

- Kościół ewangelicki pw. Zbawiciela w Bielsku

- Pisana i drukowana fraktura

- Plac teatralny w Bielsku

- Rynek w Bielsku

- Bielsko-bialska wyspa - siatka przedwojenna

- Bielsko-bialska wyspa - siatka współczesna

- Śląsk austriacki

- Andreas Olma w stroju ludowym

- Bielskie stroje ludowe

- Baltazar Damek

- Wnętrze fabryki Johanna Vogta

- Zapis wiersza Der Liga-Jirg

- Początkowe wersy spektaklu Ein Bielitzer ...

- Kolonizacja niemiecka w średniowieczu

- Bielsko-bialska na Mapie Brockhausa

- Bielska wyspa na tle innych dialektów śląskich

- Spis mieszkańców Hałcnowa 1943/1944

- Para hałcnowska w stroju weselnym

- Poświadczenie obywatelstwa z roku 1905

- Książka "Heimat Alzen" - okładka

- Dawny kościół hałcnowski

- Niemiecka pocztówka z Hałcnowa

- Widok na Hałcnów

- Dzisiejszy kościół hałcnowski

- Widok na Hałcnów z lotu ptaka

- Samogłoski hałcnowskie

- Hałcnovian monophtong vowels