Hałcnovian and Bielsko-Biała enclave

Kinship and identity

Language family and language group

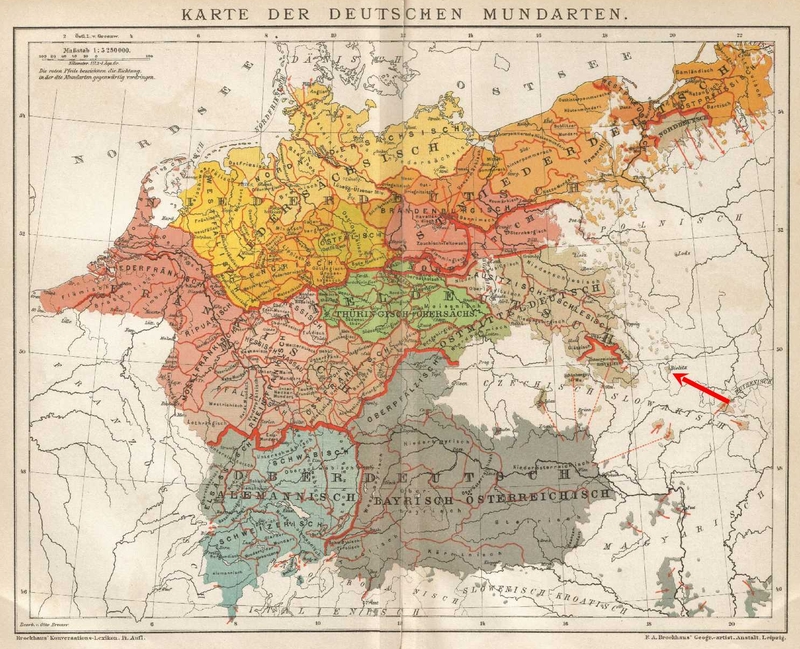

The Ethnologue language catalogue does not offer any information on the dialects of the Bielsko-Biała enclave other than Wymysorys/Wilamowicean. Based on the dialects map that exist for the German language it might be possible to classify them as East Middle German.

The Bielsko-Biała language enclave on Brockhaus' Map of German Dialects

see: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brockhaus_1894_Deutsche_Mundarten.jpg

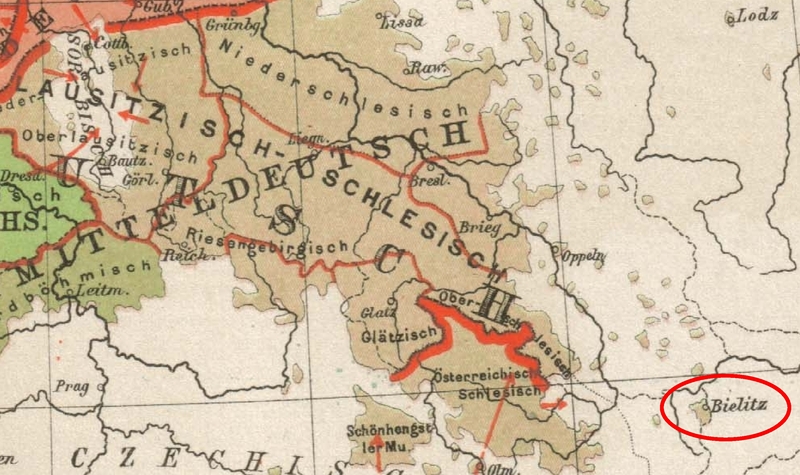

The Bielsko-Biała language enclave in the context of other Silesian dialects.

Own elaboration based on Brockaus' Map of German Dialects

see: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brockhaus_1894_Deutsche_Mundarten.jpg

Linguistic similarity

Similarity to the German language

The Bielsko-Biała dialect varieties should be doubtlessly described as High German.German is the official language of Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Germany, Belgium and one region of Italy - South Tyrole. This does not mean, however, that those living in these regions and for whom German is their native language can communicate without hindrance. The variety of forms within this language is great. That is why the importance of the standard German language, (Hochdeutsh), is so critical. This variety (for many of whom is tantamount to the term "German language) is based on Martin Luther's Bible translation. Being that the Bible was the core of his preaching, he wanted it to reach as many people as possible. That is why he believed it ought be expressed in an accessible way. This accessible way, as Luther surmised, were the dialects used in Upper Saxony and Thuringia. The existence of such a standard language was deemed more crucial when the ideas of Johann Gottfried Herder gained popularity. According to him, it was language that is the most essential part of nationhood. It made it possible to connect different peoples into one community regardless of how many polities they belonged to.

Of course, there is no objective criteria that would allow for a definite assessment of whether a given language variety is a language or (still) a dialect. The fact that a given variety has been classified in a particular way is dependent not only on linguistic consideration per se but, also, on tradition, on the way how its users identify themselves and, sometimes, even on political interest. It is, thus, custom to speak of a German language rather than of German languages as Meier & Meier did in their classification (1979: 83-83

Meier & Meier 1979 / komentarz/comment /

Meier & Meier 1979 / komentarz/comment / Meier, Georg F. & Barbara Meier 1979. Sprache, Sprachentstehung, Sprachen. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

), dividing the

), dividing the „North German language group: FRG German, GDR German, Austrian German, Swiss German, USRR German, Romanian German, North America German, French and Luxemburgish German, German language varieties in different cities, Yiddish".

It should be, thus, noted that one should not limit oneself solely to the standard German language when writing about the similarity to the German language. It is necessary to compare the given language variety to other varieties, dialects or even German languages to guarantee the comprehensiveness of the description.

The list of names which have been used to describe the dialects of Bielsko proves that linguists and historians alike associated them with the Silesian German dialects. However, it should be remembered that the emergence of these dialects is to be ascribed to the descendants of settlers in the Middle Ages who, mainly, came from different regions of today's Germany. It is even likely that once they had lived in what is now known as the Netherlands, Belgium and France. Silesian, thus, is an admixture of dialects which consists of elements from various German language varieties. Initially it probably had been be much more diversified than it was in the 20th century. Throughout the centuries of co-existence of various groups the varieties they employed became much more similar to each other. The scholars of language and history did not attempt to reach into the depths of history and did not try to determine what particular German dialects influenced the Bielitzer Mundarten Richard Ernst Wagner referred to the research known to him at the time and wrote about the obvious influence of Thuringia and Upper Saxons dialects on the Silesian varieties of German (Wagner 1935: 193

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

).

).Wilamowicean and the dialects of the Silesian language islands have not yet been subjected to thorough comparative analyses. It is justified to suspect that there might be no living speakers of any language of the Silesian language enclaves, hence this kind of analysis would have to be conducted on written materials. The Anhalt-Gatsh language island was described by Wackwitz (1932

Wackwitz 1932 / komentarz/comment /

Wackwitz 1932 / komentarz/comment / Wackwitz, Andreas 1932. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Anhalt-Gatsch in Oberschlesien in ihrer geschichtlichen Entwicklung. Plauen i. Vogtland: G: Wolff.

) whereas, e.g., Gusinde (1911

) whereas, e.g., Gusinde (1911 Gusinde 1911 / komentarz/comment /

Gusinde 1911 / komentarz/comment / Gusinde, Konrad 1911. Eine vergessene Sprachinsel im polnischen Oberschlesien (die Mundart von Schönwald bei Gleiwitz). Breslau: Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. [przedruk: 2012]

) did research on the Shewaud dialect. A reprint of Gusinde's work appeared in 2012. Trambacz (1971

) did research on the Shewaud dialect. A reprint of Gusinde's work appeared in 2012. Trambacz (1971 Trambacz 1971 / komentarz/comment /

Trambacz 1971 / komentarz/comment / Trambacz, Waldemar 1971. Die Mundart von Bojków. Versuch einer phonetisch-phonologischen Betrachtungsweise. Poznań : UAM [nieopublikowana rozprawa doktorska].

) took up this topic in his research. Yet another German language enclave (Gościęcina) was described recently by Felicja Księżyk (2008

) took up this topic in his research. Yet another German language enclave (Gościęcina) was described recently by Felicja Księżyk (2008 Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment /

Księżyk 2008 / komentarz/comment / Księżyk, Felicja 2008. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Kostenthal. Geschichte und Gegenwart. Berlin: trafo.

).

).Similarity to other languages

Opinions on Wilamowicean (and Hałcnovian) can be expressed by the words of Józef Łepkowski, a professor of archeology at the Jagielloński University. In his letter from Kęty from the 20th of September 1853, published in Gazeta Warszawska he writes the following:A peculiar thing is this speech! As if it's Yiddish, as if it's English but, obviously, kind of rings German. [...] "The language of those living in Wilamowice and Hałcnów, despite being many centuries in contact with the Slavic of the Polish kind on one hand, and of the Silesian kind on the other, retained much of its harsh gothicness; it is a Germanic dialect, but one snatched from the Middle Ages and frozen in time." Others deem the settlers as Dutchmen who arrived here during the very first religious conflicts. - I bear no knowledge on the differences between the Old German speech and the one of modernity, nor can I speak any Dutch, and so I am unable to classify this dialect - even more so that nobody except the colonists themselves can understand the language. In German or Polish they answer to a stranger, in Polish they pray but they did retain, as if mummified, their own dialect.The described area is situated at the foot of Beskidy. During the Middle Ages and the early periods of Modernity this mountainous area was inhabited by settles from the Balkan Peninsula and today's Romania, Valakh shepherds (Putek 1938

(translated from the Polish original as quoted in Filip 2005: 150)

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment /

Putek 1938 / komentarz/comment / Putek, Józef 1938. O zbójnickich zamkach, heretyckich zborach i oświęcimskiej Jerozolimie. Kraków: Drukarnia Przemysłowa.

). Although they have been ruthenisized by Eastern Slavs and polonised on the territory of Poland the traces of their language can be traced in Polish, especially in the vocabulary of sheep herders. Some of these words (perhaps via Polish) have made their way to other Bielsko dialects. In Bukowski's dictionary (1860: 170

). Although they have been ruthenisized by Eastern Slavs and polonised on the territory of Poland the traces of their language can be traced in Polish, especially in the vocabulary of sheep herders. Some of these words (perhaps via Polish) have made their way to other Bielsko dialects. In Bukowski's dictionary (1860: 170 Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment /

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment / Bukowski, Jacob 1860. Gedichte in der Mundart der deutschen schlesisch-galizischen Gränzbewohner resp. von Bielitz-Biala. Bielitz: Zamarski. [przedruk w: Wagner 1935: 1-190].

) the word Brens is translated as Brimsenkäse.The dialects of the Southern part of the language enclave use this word to denote the smoked sheep milk cheese - bryndza in Polish. Also, since the 16th century inhabitants of Biała started to use Valakh surnames (Polak 2010: 26

) the word Brens is translated as Brimsenkäse.The dialects of the Southern part of the language enclave use this word to denote the smoked sheep milk cheese - bryndza in Polish. Also, since the 16th century inhabitants of Biała started to use Valakh surnames (Polak 2010: 26 Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Polak 2010 / komentarz/comment / Polak, Jerzy (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom II. Biała od zarania do zakończenia I wojny światowej (1918). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

).

).Contacts with Polish

The Polish and German varieties spoken on the discussed territory were in constant contact and continued to influence each other. It is possible to possible some of the "geopolitical" determinants that were responsible for this phenomenon. The influence of Polish was stronger on the fringes of the language enclave where the German-speaking population did not constitute a majority. Also, as Richard Ernst Wagner noticed, those dialects that once were spoken on the territory of former Galicia were extensively polonised due to historical reasons (1935: XV Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

).

). In Bukowski's dictionary of the Biała dialect (1860

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment /

Bukowski 1860 / komentarz/comment / Bukowski, Jacob 1860. Gedichte in der Mundart der deutschen schlesisch-galizischen Gränzbewohner resp. von Bielitz-Biala. Bielitz: Zamarski. [przedruk w: Wagner 1935: 1-190].

) there are around 10 words of Polish origin. Three among them require further consideration:

) there are around 10 words of Polish origin. Three among them require further consideration:- Pailz-la – paluszek (diminutive of finger)

- ver-zamek-ajn – zamknąć (to close)

- Zofa-gratsch – krok w tył (a step back)

Borrowings from Polish can be also found in the texts of Karl Olma (Olma 1983

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

, Zöllner 1988

, Zöllner 1988 Zöllner 1988 / komentarz/comment /

Zöllner 1988 / komentarz/comment / Zöllner Michael 1988. Alza wo de Putter wuor gesalza. Gedichte und Lieder einer untergehender Mundart. Dülmen: Oberschlesischer Heimatverlag.

). For example, this vocabulary includes words present in the religious sphere: uopüst meaning "odpust" (indulgence) (Olma 1983: 34

). For example, this vocabulary includes words present in the religious sphere: uopüst meaning "odpust" (indulgence) (Olma 1983: 34 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

); in local cuisine: babuwka -"yeast cake", "babka" (Olma 1983: (102), or borrowings of personal names -Kaschka - "Kaska" (Zöllner 1988: 102

); in local cuisine: babuwka -"yeast cake", "babka" (Olma 1983: (102), or borrowings of personal names -Kaschka - "Kaska" (Zöllner 1988: 102 Zöllner 1988 / komentarz/comment /

Zöllner 1988 / komentarz/comment / Zöllner Michael 1988. Alza wo de Putter wuor gesalza. Gedichte und Lieder einer untergehender Mundart. Dülmen: Oberschlesischer Heimatverlag.

)). What can be also observed in Olma's works is the presence of Polish honorific addresses in the vocative in purely German sentences: "Panie" (Sir!), e.g. Panie, ein Kreuzer ist auch Geld - A kreuzer is money as well, Sir! (Olma 1983: 40

)). What can be also observed in Olma's works is the presence of Polish honorific addresses in the vocative in purely German sentences: "Panie" (Sir!), e.g. Panie, ein Kreuzer ist auch Geld - A kreuzer is money as well, Sir! (Olma 1983: 40 Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment /

Olma 1983 / komentarz/comment / Olma, Karl 1983. Heimat Alzen. Versuch einer Chronik über 550 Jahre bewegter Geschichte. Pfingsten: Heimatgruppe Bielitz-Biala e.V., Zweiggruppe Alzen.

).

).Given the small amounts of written material in the local dialects spoken in towns and villages adjacent to Bielsko, it is difficult to estimate to what extent has the contact with the Polish language influenced their syntax. Wenker's example sentences (which will be discussed further in this work) might provide some information on this topic as, in some cases, they exhibit a syntax different than that of the standard German language.

Language, dialect, a group of dialects?

The status according to its speakers

As it has been said before, there is no objective border between what constitutes a language and what constitutes a dialect. In essence the distinction between languages, dialects and sub-dialects is abstract at best. Perhaps the classification can support linguistics in their attempt at systemizing languages. Nevertheless, for entire centuries speakers of a given variety did not pay any attention to whether their variety is classified by others as language/dialect or sub-dialect. This changed during the 19th century when intellectual, and then politicians, conceptualised language as one of the decisive elements constitution a nation. It was no longer serfdom but speaking a given language that ultimately determined the belonging to a nation. What followed is the popularisation of the broad term of "national language" which would include subordinate dialects.Taking that into account, it can be assumed that for the vast majority of the inhabitants of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave it was plainly immaterial whether the language variety they employed was considered a language, dialect or sub-dialect - at least until the beginning of the 20th century. Of course, they were aware of the differences between their way of speaking - between päuersch(peasant) and standard German. Nonetheless, the did not conceptualise this differences into categorizations of 'language" vs "dialect".

Among the scholars of the dialects of Bielsko one could list only those who have spent most of their lives in Bielsko, Biała or any of the nearby towns or villages. These scholars have been intellectuals who were or are tied to this region either by their birth here or by long years of work, e.g. Richard Ernst Wagner (1935

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

) who was a Protestant churchman. Walter Kuhn, Ervin Hanslik, Gustav Waniek and Friedrich Wilhelm Bock were teachers in high schools and universities. Jacob Bukowski was a medical doctor of high excellence. In German the term has a broader meaning than the Polish "dialekt". Podręczny Słownik Języka Niemieckiego (Dictionary of German) defines it as a "narzecze, gwara, dialekt", three slightly distinct concepts in Polish (Chodera, Kubica 1984: 557

) who was a Protestant churchman. Walter Kuhn, Ervin Hanslik, Gustav Waniek and Friedrich Wilhelm Bock were teachers in high schools and universities. Jacob Bukowski was a medical doctor of high excellence. In German the term has a broader meaning than the Polish "dialekt". Podręczny Słownik Języka Niemieckiego (Dictionary of German) defines it as a "narzecze, gwara, dialekt", three slightly distinct concepts in Polish (Chodera, Kubica 1984: 557 Chodera i Kubica 1984 / komentarz/comment /

Chodera i Kubica 1984 / komentarz/comment / Chodera, Jan i Stefan Kubica 1984. Podręczny słownik niemiecko-polski. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna.

). It is only Richard Ernest Wagner (1935: XVI

). It is only Richard Ernest Wagner (1935: XVI Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment /

Wagner 1935 / komentarz/comment / Wagner, Richard Ernst 1935. Der Beeler Psalter. Die Bielitz-Bialaer deutsche mundartliche Dichtung. Katowice: Kattowitzer Buchdruckerei u. Verlags – Sp. Akc.

) that calls the Bielsko dialects die Bielitzer Mundarten. It was also Bock that paid attention to the linguistic diversity within the Bielsko-Biała language enclave itself (Bock 1916a: 219

) that calls the Bielsko dialects die Bielitzer Mundarten. It was also Bock that paid attention to the linguistic diversity within the Bielsko-Biała language enclave itself (Bock 1916a: 219 Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment /

Bock 1916a / komentarz/comment / Bock Friedrich 1916b. Der Liega-Jirg. Gedicht in der Bielitzer Mundart. Bielitz: Friedrich Bock. [przedruk w: Wagner 1936: 222-230].

). Karl Olma, who was a poet and amateur-historian born in Hałcnów, described his local variety as die Mundart

). Karl Olma, who was a poet and amateur-historian born in Hałcnów, described his local variety as die MundartThose who use the Halcnovian variety nowadays decide to call it a language.

Status according to different organizations - codes on the dialects/languages.

So far no code has been granted to the Bielsko German dialects by any standard tool for classifying languages. Silesian dialects of the German language which are related to the Bielsko dialects have been granted the code sli by the Internet catalogue Ethnologue which uses the ISO-639-3 standard.The language classification catalogue employed by L'Observatoire Linguistique, Linguasphere,ascribed the code 52-ACB-do to the Silesian German language varieties (http://www.linguasphere.info/lcontao/tl_files/pdf/index/LS_index_r-s.pdf). The MARC 21 standard employed by the Library of Congress does not include them.Identity

National and ethnic

The ethnic and national identity of the German-speaking inhabitants of Bielsko, Biała and their adjacent settlements in the First Polish Republic period cannot be determined from any known sources - it may be that there are none. It can be assumed that they were aware of the existing differences between them and their Polish-speaking neighbours; at that time, however, identity was formulated mostly by a combination of religious, class and country elements. It should be also worth noting that in the period of the First Polish Republic, the German language was the native language of many noble houses and gords.As Kleczkowski (1915: 390

Kleczkowski 1915 / komentarz/comment /

Kleczkowski 1915 / komentarz/comment / Kleczkowski, Adam 1915. „Dyalekty niemieckie na ziemiach polskich”, w: H. Ułaszyn, i in. Język polski i jego historya z uwzględnieniem innych języków na ziemiach polskich. cz. II. Kraków: Nakładem Akademii Umiejętności. Ss. 387-394.

) wrote: "The powerful 14th and 15th century German colonisation of the Lesser Poland region weakens with time, and in the second half of the 18th century, still in the period of Polish reign, it starts anew, initially in Silesia".

) wrote: "The powerful 14th and 15th century German colonisation of the Lesser Poland region weakens with time, and in the second half of the 18th century, still in the period of Polish reign, it starts anew, initially in Silesia".

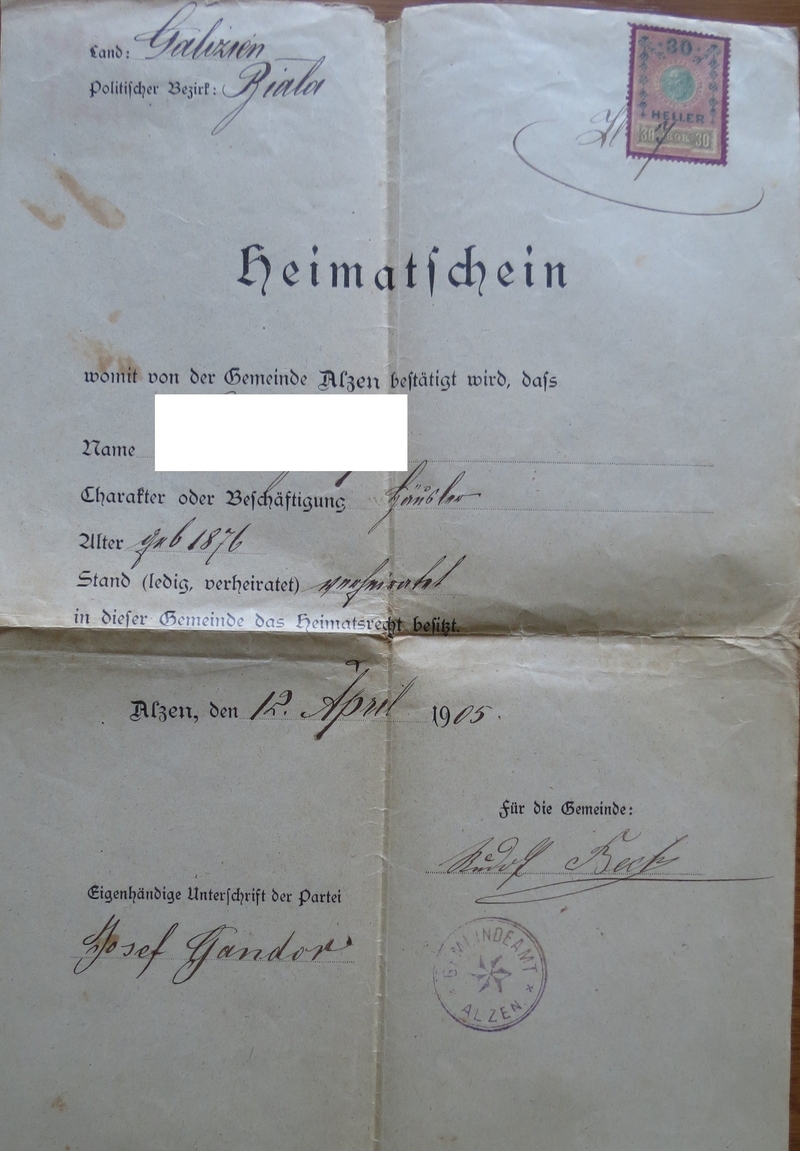

Citizenship attestation from 1905, issued for one of the informants. Private source

Belonging to a given country-state was still a very strong factor in determining one's identity, even in the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, territories on both sides of the river Biała were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Nonetheless, ideals of nationalism began to spread first in the towns, and later within rural areas. The clash between this new type of identity based on one's "nationality" and the old one based on close ties with one's small homeland and the country-state is depicted in the reminiscent article by Eugeniusz Bilczewski, a teacher from Wilamowice:

Peaceful and placid as they were, and seeing themselves primarily as "Wilamowiceans", they were now faced with the demand to formulate their identity at a national level. They used to say "wir sein esterreichyn", we are Austrians as we live in Austria. Every subjects in this monarchy was considered an Austrian regardless of the language they spoke. Austria and Franz Joseph I were symbols of power and strength, Vienna - welfare and a dream of every single citizen (as quoted in Filip 2005: 162).As time passed, however, the fact of speaking a given language began to be very strongly associated with a given national identity. Most people speaking a German dialect would, naturally, consider themselves German. Nonetheless, there was no rule as can be clearly seen in the memories of Konrad Korzeniowski, a German-speaking Pole from Bielsko:

Once, on its opposite side, some man was trying to hang the Hakenkreuzfahne (Hitler's flag) on Schimank's shop. He was balancing on the narrow eave of the shop and we kept wondering - will he fall or not? He didn't fall down but the army truck parked there could not start despite the driver's furious attempts - the wheels were slipping on ice and the help of the "soldaten" was completely in vain. I laughed while shouting "Gut so den Deutschen!" (it serves you right, you Germans!) but my grandma cautioned me in all seriousness: „Aber Konrad, so darf man nicht sagen!” (But Conrad, you shouldn't say things like that!) (Polak 2012: 323Polak 2012 / komentarz/comment /

Polak, Jerzy 2012. Bielsko-Biała w zwierciadle czasu. Wspomnienia mieszkańców z lat 1900-1945. Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego.).

Religious identity

Catholicism was the dominant religion among the colonists settling in the vicinity of Bielsko. However, in the 15th century the Duchies of Oświęcim and Cieszyn found themselves under Czech influence which led to the fact that a portion of the inhabitants of the Bielsko-Biała language enclave accepted the Hessite religion as their own. By 1424, Hussitism became the dominant religion of Wilamowice, Kozy and Lipnik (Wurbs 1981: 16 Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment /

Wurbs 1981 / komentarz/comment / Wurbs, Gerhard 1981. Die deutsche Sprachinsel Bielitz-Biala. Eine Chronik. Wien.

). Not for long, however, as the area would turn back to Catholicism, a state which would last until the reformation period. The teaching of Martin Luther found fertile ground in the regions of Bielsko and Biała. In the end, however, the policies of successive rules influenced the demographics in such a way that by the beginning of the 20th century the majority of the population living on the Western bank of the Biała river accepted Evangelism as can be evidences by the figures of the 1847 national census (Panic 2010: 430

). Not for long, however, as the area would turn back to Catholicism, a state which would last until the reformation period. The teaching of Martin Luther found fertile ground in the regions of Bielsko and Biała. In the end, however, the policies of successive rules influenced the demographics in such a way that by the beginning of the 20th century the majority of the population living on the Western bank of the Biała river accepted Evangelism as can be evidences by the figures of the 1847 national census (Panic 2010: 430 Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment /

Panic 2010 / komentarz/comment / Panic, Idzi (red.) 2010. Bielsko-Biała. Monografia miasta. Tom I. Bielsko od zarania do wybuchu wojen śląskich (1740). Bielsko-Biała: Wydział Kultury i Sztuki Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.

):

):| Evangelical | Catholic | |

| Bielsko | 5915 | 1850 |

| Stare Bielsko | 1600 | 450 |

| Bystra | 278 | 102 |

| Kamienica | 1222 | 495 |

| Mikuszowice | 291 | 117 |

| Olszówka Górna | 138 | 70 |

| Olszówka Dolna | 157 | 75 |

| Wapienica | 807 | 89 |

In Wilamowice and Hałcnów Catholicism was the preferred denomination. In Biała itself most of the population was Catholic as well. Nonetheless, there were Evangelic among the German-speaking population of the town.

It is also worth to mention that in the 17th century Calvinism had its share of followers east of the Biała river, in Kozy and Wilamowice as well (Urban 2001: 110-111

Urban 2001 / komentarz/comment /

Urban 2001 / komentarz/comment / Urban, Wacław 2001. „W granicach królestwa Polskiego 1457-1772”. w: Barciak 2001: 98-115.

). It cannot be ruled out, as well, that the local Jewry spoke some of the Bielsko dialects. Nonetheless, most of those who lived on the territory of former Galicia used Yiddish as their native tongue. In Silesia, many of them became assimilated to the local German culture and language. Both groups, however, could possess at least a passive knowledge of the regional dialects.

). It cannot be ruled out, as well, that the local Jewry spoke some of the Bielsko dialects. Nonetheless, most of those who lived on the territory of former Galicia used Yiddish as their native tongue. In Silesia, many of them became assimilated to the local German culture and language. Both groups, however, could possess at least a passive knowledge of the regional dialects.

Evangelic Church dedicated to The Savour in Bielsko, see: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bielsko-Bia%C5%82a,_Church_of_Saviour_in_1860.jpg?uselang=pl

ISO Code

no separate code for the Bielitz-Biala Sprachinsel or Hałcnovian

possible code: hlc

possible code: hlc

- Biogram

- Pieśń Olmy 1

- Pieśń Olmy 2

- Pieśn Olmy 3

- Pieśń Olmy 4

- Składanka pieśni Olmy

- Składanka pieśni Olmy 2

- Pieśn Olmy 5

- Modlitwa dziecięca

- Bajka o Wietrze Północnym i Słońcu

- Opowiadanie o weselu

- Opowiadanie o głównych zajęciach hałcnowian przed wojną

- Opowiadanie/rozmowa o kościele hałcnowskim

- Dialog o strojach hałcnowskich

- Rozmowa o hałcnowiankach

- Krótki wierszyk

- Dwa dowcipy hałcnowskie

- Opowiadanie o ostatnich tygodniach

- Pieśń Olmy w wykonaniu męskim

- Rozmowa o życiu dzieci przed wojną

- Rozmowa o Świętach Bożego Narodzenia

- Rozmowa o dzieciństwie

- Zdania Wenkera

- Żart o wilamowianach (video)

- Opowiadanie o zalotach

- Pieśń hałcnowska - wersja video

- Opowiadanie o odpuście

- Rozmowa o jedzeniu (video)

- Dokumenty hałcnowskie sprzed wieków

- Informatorzy

- Zbiór pieśni hałcnowskich

- Stroje hałcnowskie

- Rozmowa o wilamowianach (doświadczenia z dzieciństwa)

- Słowniczek polsko-hałcnowski

- Lista Swadesha

- Arkusz Wenkera

- Zasady zapisu

- Słowniczek bielski

- Schatzla, eta komma wir [tekst]

- Alzner Hymne [tekst]

- Rozmowa o wsi przed wojną

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia na KNG

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia na SNBHJ w Toruniu

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia w Kamieniu Śląskim

- Prezentacja z wystąpienia na OKH w Poznaniu

- Bock 1916b

- Weiser 1937

- Waniek 1897

- Olma 1983

- Polak 2012

- Chorąży i Chorąży 2010b

- Putek 1938

- Chorąży i Chorąży 2010c

- Panic 2010

- Panic 2002

- Hanslik 1938

- Kuhn 1981

- Polak 2010

- Hanslik 1908

- Meier & Meier 1979

- Zöllner 1988

- Chodera i Kubica 1984

- Urban 2001

- Janoszek i Zmełty 2004

- Mickler 1938

- Wagner 1937a

- Wagner 1937b

- Wagner 1938

- Gusinde 1911

- Spyra 2010

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- Wiadomości na temat zaimków hałcnowskich

- Odmiana wybranych czasowników hałcnowskich

- Wiadomości na temat rodzajników hałcnowskich

- Zasady transkrypcji nagrań hałcnowskich

- Skrócony opis fonetyki/fonologii hałcnowskiej

- osoby z Hałcnowa,Bielska,Białej zmarłe w Oświęcimi

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Mapa bielsko-bialskiej wyspy językowej

- Arkusz Wenkera z DiWA

- fotografia pary z Hałcnowa w Wilamowicach

- akt małżeństwa

- Dworzec kolejowy w Bielsku

- Księstwo cieszyńskie w roku 1746

- strona tytułowa Bukowski 1860

- Panorama Bielska

- Kościół ewangelicki pw. Zbawiciela w Bielsku

- Pisana i drukowana fraktura

- Plac teatralny w Bielsku

- Rynek w Bielsku

- Bielsko-bialska wyspa - siatka przedwojenna

- Bielsko-bialska wyspa - siatka współczesna

- Śląsk austriacki

- Andreas Olma w stroju ludowym

- Bielskie stroje ludowe

- Baltazar Damek

- Wnętrze fabryki Johanna Vogta

- Zapis wiersza Der Liga-Jirg

- Początkowe wersy spektaklu Ein Bielitzer ...

- Kolonizacja niemiecka w średniowieczu

- Bielsko-bialska na Mapie Brockhausa

- Bielska wyspa na tle innych dialektów śląskich

- Spis mieszkańców Hałcnowa 1943/1944

- Para hałcnowska w stroju weselnym

- Poświadczenie obywatelstwa z roku 1905

- Książka "Heimat Alzen" - okładka

- Dawny kościół hałcnowski

- Niemiecka pocztówka z Hałcnowa

- Widok na Hałcnów

- Dzisiejszy kościół hałcnowski

- Widok na Hałcnów z lotu ptaka

- Samogłoski hałcnowskie

- Hałcnovian monophtong vowels