(polski) jidysz

Nazwa

lingwonimy i etnonimyendolingwonimy

- loszn aszkenaz לשון-אשכּנז (dosł. ‘język Aszkenaz’, termin używany w źródłach pisanych w języku hebrajsko-aramejskim),

- tajcz טײַטש (dosł. ‘niemiecki’, później metonimicznie [1]

przyp01 / komentarz/comment /

przyp01 / komentarz/comment /

Metonimia polega na przeniesieniu podstawowego znaczenia danego słowa na część elementów pozostających w jakimś związku z tą rzeczą lub na odwrót – rzecz określana jest przez część elementów z nią związanych. ‘tłumaczenie’),

‘tłumaczenie’), - iwre tajcz עברי-טײַטש (dosł. ‘hebrajsko-niemiecki’),

- jidisz-tajcz יידיש-טײַטש (dosł. ‘żydowsko-niemiecki’),

- polisz-tajcz פּויליש-טײַטש (dosł. ‘polsko-niemiecki’),

- jidysz יידיש (dosł. ‘żydowski’, w źródłach pisanych w języku jidysz od XX w.).

- język żydowski,

- żargon (nazwa wprowadzona przez zwolenników Haskali [2]

przyp02 / komentarz/comment /

przyp02 / komentarz/comment /

Haskala to oświeceniowy ruch działający w XIX w., początkowo na terenie Niemiec. , w językach słowiańskich początkowo bez konotacji pejoratywnej),

, w językach słowiańskich początkowo bez konotacji pejoratywnej), - jidysz (< ang. Yiddish < jid. jidisz < niem. jüdisch ‘żydowski’ < hebr. jehudit ‘żydowski’ < hebr. Juda ‘jedno z 12 plemion Izraela’).

- jid ייד, l.mn. jidn (‘Żyd’),

- ben Isroel ישראל בנ (dosł. ‘syn Izraela’), używane często w l.mn. bnej Isroel בני ישראל (dosł. ‘dzieci Izraela’),

- Isroel ישראל (‘Izrael’),

- jidisze tochter טאָכטער יידישע (tylko w odniesieniu do kobiet, dosł. ‘żydowska córa’),

- jidisz kind יידיש קינד (tylko w odniesieniu do kobiet, dosł. ‘żydowskie dziecko’).

- Żyd,

- Izraelita.

Historia i geopolityka

I Rzeczpospolita

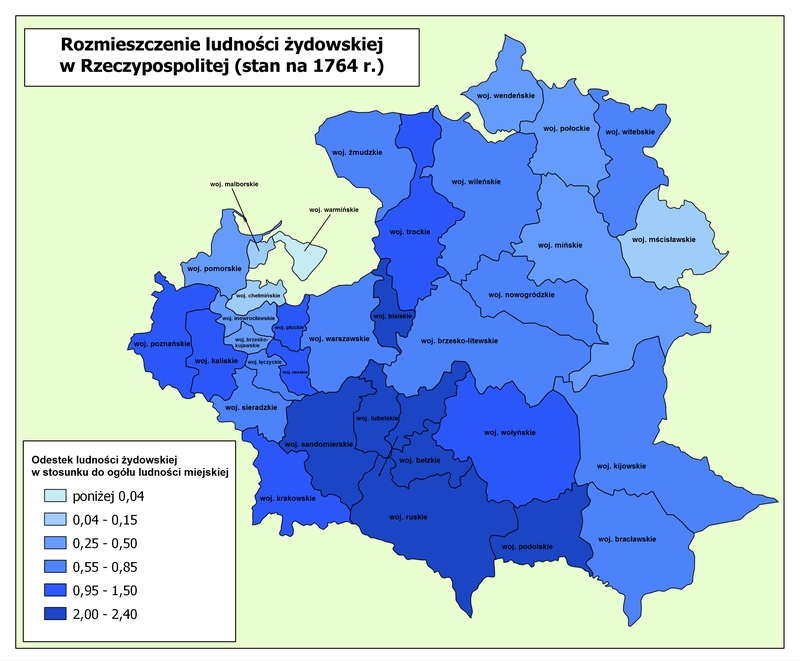

Rozmieszczenie ludności żydowskiej w I Rzeczypospolitej (stan na 1764 r.), red. mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz.

Okres międzywojenny

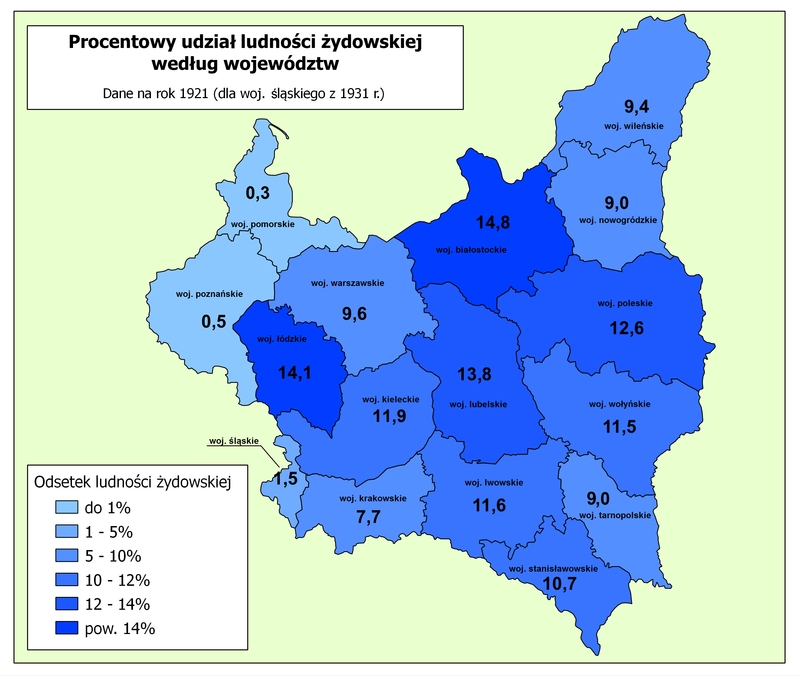

Procentowy udział ludności żydowskiej według województw II Rzeczypospolitej - dane z 1921 r. (dla woj. śląskiego z 1931 r.), red. mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz.

Współczesność

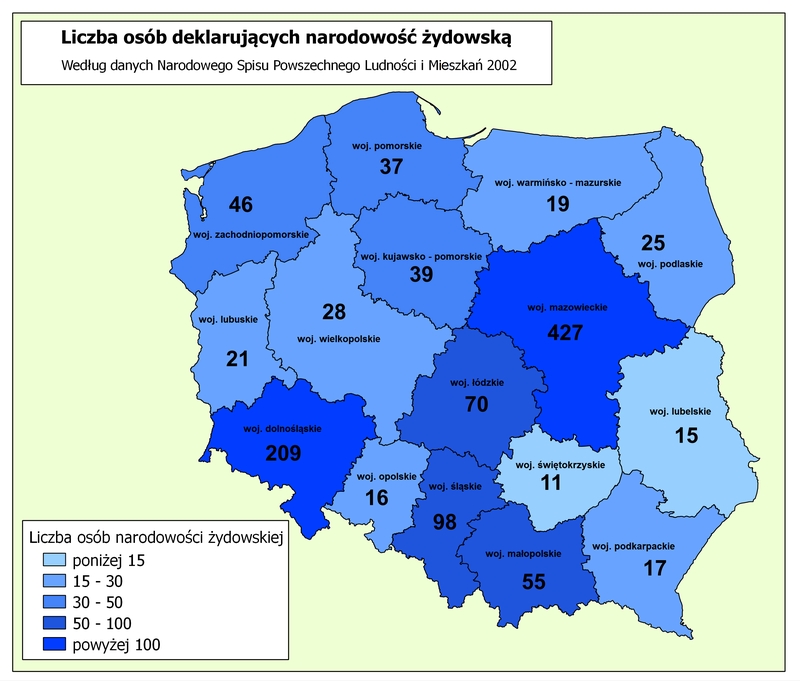

Lista osób deklarujących narodowość żydowską według danych Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2002 r, red. mapy: Jacek Cieślewicz.

Gdzie jeszcze mówi się w danym języku?

Lista krajów, w których mówi się w jidysz, według liczby użytkowników: Stany Zjednoczone, Wielka Brytania, Izrael, Belgia, Rosja, Argentyna, Ukraina, Rumunia, Białoruś, Litwa, Australia, Mołdawia, Panama, Puerto Rico, Republika Południowej Afryki, Urugwaj.

Historia

Krótki rys historyczny Żydów w Polsce

Niezależnie od teorii powstania jidysz faktem jest, że język ten zaczął być używany na terenach polskich wraz z przypływem Żydów aszkenazyjskich z Zachodu. Aszkenaz to biblijna nazwa, którą Żydzi nadali terenom średniowiecznych Niemiec, będących jednym z celów ich wędrówek.

Pierwsze ślady osadnictwa żydowskiego na ziemiach polskich pochodzą z Przemyśla z końca XI w. Później Żydzi emigrowali na terytoria polskie, uciekając m.in. przed pierwszą wyprawą krzyżową (1096 r.-1099 r.). Główna fala emigracji rozpoczęła się jednak około XIII w. Sprzyjającym czynnikiem było wydanie przez Bolesława Pobożnego w 1264 r. Statutów Kaliskich, których obszar obowiązywania został rozszerzony przez Kazimierza Wielkiego w 1334 r. na teren całego Królestwa Polskiego. Działanie takie wynikało z potrzeb ekonomicznych Korony, która chciała rozwijać polskie miasta poprzez imigrację żydowską (także niemiecką). Żydzi zostali objęci ochroną książęcą oraz umożliwiono im tworzenie gmin żydowskich (kahałów), które odznaczały się względną autonomią organizacyjną. W wielu przypadkach uprzywilejowana pozycja żydowskich rzemieślników czy też kupców wywoływała opór m.in. rywalizujących z nimi cechów chrześcijańskich. Sprzeciwiało się także duchowieństwo katolickie, które nawoływało do odsunięcia Żydów od pełnienia funkcji publicznych. Nakazywano im także noszenie wyróżniających się szat. W Polsce jednak przepisy zmuszające Żydów do noszenia tzw. znaków hańby [3] przyp03 / komentarz/comment /

przyp03 / komentarz/comment /

Znaki hańby służyły do wizualnego naznaczenia Żydów, którzy w ten sposób mieli odróżniać się od reszty społeczeństwa. Miało to też zapobiegać "mieszaniu się" społeczności. W Europie Zachodniej już w średniowieczu Żydzi zmuszani byli do noszenia żółtych różnokształtnych łat przypiętych do ubrania, czy też specjalnych nakryć głowy. W niektórych krajach europejskich praktyka zewnętrznego naznaczania Żydów utrzymała się do XIX w. W czasie Zagłady naziści ożywili symbolikę stygmatyzacji Żydów poprzez wizualne naznaczenie. , odróżniających ich od reszty społeczeństwa, nigdy nie weszły w życie. Mimo względnej tolerancji panującej w Polsce na przestrzeni wieków Żydzi doświadczyli wielu antyżydowskich wystąpień. Niemniej Korona Królestwa Polskiego była dla nich w XIV w. schronieniem, jakiego nie zaznali w innych krajach Europy. Na początku XVI w. Zygmunt I Stary wprowadził dodatkowe przywileje dla Żydów oraz kary dla miast, które dopuściłyby do wystąpień antyżydowskich. Polska pod panowaniem Zygmunta I Starego i Zygmunta II Starego nazywana była rajem dla Żydów (paradis Judaeorum). Stała się ona rajem nie tylko dla żydowskich kupców czy rzemieślników, ale także dla żydowskich duchownych i uczonych. Talmudyści mieszkający i pobierający nauki w jesziwach [4]

, odróżniających ich od reszty społeczeństwa, nigdy nie weszły w życie. Mimo względnej tolerancji panującej w Polsce na przestrzeni wieków Żydzi doświadczyli wielu antyżydowskich wystąpień. Niemniej Korona Królestwa Polskiego była dla nich w XIV w. schronieniem, jakiego nie zaznali w innych krajach Europy. Na początku XVI w. Zygmunt I Stary wprowadził dodatkowe przywileje dla Żydów oraz kary dla miast, które dopuściłyby do wystąpień antyżydowskich. Polska pod panowaniem Zygmunta I Starego i Zygmunta II Starego nazywana była rajem dla Żydów (paradis Judaeorum). Stała się ona rajem nie tylko dla żydowskich kupców czy rzemieślników, ale także dla żydowskich duchownych i uczonych. Talmudyści mieszkający i pobierający nauki w jesziwach [4] przyp04 / komentarz/comment /

przyp04 / komentarz/comment /

Wyższa szkoła talmudyczna dla nieżonatych chłopców. Po ukończeniu jesziwy niektórzy uczniowie otrzymywali tzw. simchę (słowo pochodzenia hebrajskiego, 'upoważnienie'), która uprawniała do wykonywania zawodu rabina. w Polsce cieszyli się sławą w całej ówczesnej Europie. W Krakowie też powstała pierwsza żydowska drukarnia, która drukowała książki w języku hebrajskim i jidysz. W 1579 r. król Stefan Batory utworzył Sejm Czterech Ziem (Waad Arba Aracot ועד ארבע ארצות), który obradował w latach 1581-1764 i był centralnym organem samorządu wszystkich Żydów mieszkających na terenach Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów. Tak zwany żydowski parlament stanowił precedens na skalę ówczesnej Europy. Regulował on sprawy dotyczącego niemalże każdego obszaru życia społeczności żydowskiej.

w Polsce cieszyli się sławą w całej ówczesnej Europie. W Krakowie też powstała pierwsza żydowska drukarnia, która drukowała książki w języku hebrajskim i jidysz. W 1579 r. król Stefan Batory utworzył Sejm Czterech Ziem (Waad Arba Aracot ועד ארבע ארצות), który obradował w latach 1581-1764 i był centralnym organem samorządu wszystkich Żydów mieszkających na terenach Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów. Tak zwany żydowski parlament stanowił precedens na skalę ówczesnej Europy. Regulował on sprawy dotyczącego niemalże każdego obszaru życia społeczności żydowskiej.

Jesziwas Chachmej Lublin została założona w 1930 r. przez rabina Majera Szapirę. Jesziwas Chachmei Lublin była centrum studiów nad Torą i dawała świadectwo istnienia w tej części Polski kilkuwiecznej kultury, nauki i autonomii żydowskiej.

W Lublinie raz do roku (drugi raz w Jarosławiu) obradował w latach 1581-1764 Sejm Czterech Ziem.

Symbolicznym końcem złotego wieku bytności Żydów na ziemiach polskich było powstanie kozackie Bohdana Chmielnickiego, które wybuchło w 1648 r. Ocenia się, że w wyniku rzezi kozackich, najazdów rosyjskich i potopu szwedzkiego (1655 r.-1660 r.) liczba zabitych Żydów wyniosła około 120 tys., a samo powstanie Chmielnickiego nazywane jest w żydowskiej historiografii Pierwszą Zagładą. Wyniszczony kraj odbudowywał się powoli, także gminy żydowskie na nowo musiały budować swoją egzystencję. W tym okresie doszło do wyłonienia się z judaizmu nowych ruchów religijnych, takich jak: sabataizm [5] przyp05 / komentarz/comment /

przyp05 / komentarz/comment /

XVII wieczny ruch mesjanistyczny, który zakładał surową ascezę, głosząc jednocześnie radość życia. Odrzucał praktyki judaizmu. Jego twórcą był Sabatai Cwi (Cała & Węgrzynek & Zalewska 2000:294). czy frankizm [6]

czy frankizm [6] przyp06 / komentarz/comment /

przyp06 / komentarz/comment /

Ruch religijny skupiony wokół Jakuba Franka, który proklamował się Mesjaszem. Nauczał, że kontakt z Bogiem można osiągnąć poprzez radość życia i ekstazę, zwłaszcza seksualną. . Najważniejszym ruchem, który powstał w tym okresie i działa do dziś był chasydyzm.

. Najważniejszym ruchem, który powstał w tym okresie i działa do dziś był chasydyzm.

W 1764 r., w roku elekcji Stanisława Augusta Poniatowskiego, sejm konwokacyjny rozwiązał Sejm Czterech Ziem, a podatek pogłówny [7] przyp07 / komentarz/comment /

przyp07 / komentarz/comment /

Podatek nakładany bezpośrednio na osobę podatnika. pobierany od gmin żydowskich został zwiększony. Panujące w społeczeństwie polskim nastroje antysemickie spowodowały, że Sejm wprowadził specjalne regulacje, które zezwalały Żydom na wykonywanie zawodów ustalonych w ramach porozumienia z poszczególnymi miastami.

pobierany od gmin żydowskich został zwiększony. Panujące w społeczeństwie polskim nastroje antysemickie spowodowały, że Sejm wprowadził specjalne regulacje, które zezwalały Żydom na wykonywanie zawodów ustalonych w ramach porozumienia z poszczególnymi miastami.

Po trzech kolejnych rozbiorach Polski ludność żydowska znalazła się pod panowaniem trzech różnych władz zaborczych. Ich losy w każdym przypadku były inne.

W zaborze pruskim podejmowano próby mające na celu asymilację społeczności żydowskiej z ludnością niemiecką. W wyniku dekretu z 1797 r. odgórnie nadano Żydom niemiecko brzmiące nazwiska. Zdjęto z nich niektóre ograniczenia prawne, ale z drugiej strony odebrano np. wewnętrzne sądownictwo. Władze pruskie podzieliły społeczność żydowską na tzw. Żydów „naturalizowanych” i „tolerowanych”. Ci pierwsi cieszyli się pełnią swobód obywatelskich, pod warunkiem biegłej znajomości języka niemieckiego oraz odpowiedniego statusu majątkowego. Żydzi „tolerowani” stanowili ubogą część społeczeństwa żydowskiego.

W zaborze rosyjskim zastosowano podobne metody asymilacji. Najważniejszym rozporządzeniem, wydanym za panowania Katarzyny II, było zrównanie statusu prawnego Żydów z resztą społeczeństwa. Pielęgnowanie żydowskości mogło spotkać się z prześladowaniami ze strony lokalnej ludności. Polityka asymilacyjna częściowo spowodowała, że Polacy zaczęli utożsamiać Żydów z zaborcą [8] przyp08 / komentarz/comment /

przyp08 / komentarz/comment /

Więcej na temat lojalności wobec lokalnych władz, nie tylko rosyjskich, jako ogólnej zasadzie panującej w społeczności żydowskiej por. Wodziński 2008: 249. , co w późniejszych latach prowadziło do wzrostu antyżydowskich nastrojów. Po nieudanym zamachu na cara Aleksandra II, przeprowadzonym przez Żydówkę Hesię Helfman, odpowiedzialność za ten czyn została przeniesiona na całą społeczność żydowską. Doszło do fali pogromów w wielu miastach Cesarstwa Rosyjskiego. Pogarszająca się bieda i prześladowania doprowadziły do ukształtowania się w obrębie społeczeństwa żydowskiego ruchów socjalistycznych i syjonistycznych, także do emigracji. Dopiero rewolucje: lutowa i październikowa, zmieniły sytuację Żydów w Rosji, kiedy to zostali uznani przez komunistów za ofiary carskich prześladowań.

, co w późniejszych latach prowadziło do wzrostu antyżydowskich nastrojów. Po nieudanym zamachu na cara Aleksandra II, przeprowadzonym przez Żydówkę Hesię Helfman, odpowiedzialność za ten czyn została przeniesiona na całą społeczność żydowską. Doszło do fali pogromów w wielu miastach Cesarstwa Rosyjskiego. Pogarszająca się bieda i prześladowania doprowadziły do ukształtowania się w obrębie społeczeństwa żydowskiego ruchów socjalistycznych i syjonistycznych, także do emigracji. Dopiero rewolucje: lutowa i październikowa, zmieniły sytuację Żydów w Rosji, kiedy to zostali uznani przez komunistów za ofiary carskich prześladowań.

W zaborze austriackim sytuacja społeczności żydowskiej była najgorsza. W Galicji na przełomie XVII i XVIII w. mieszkało najwięcej Żydów z byłej Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów. Żyli oni w dużej nędzy, co spowodowane było złą sytuacją gospodarczą panującą na tamtych terenach. Także władze austriackie podejmowały próby asymilacji Żydów z pozostałą ludnością. Panująca w zaborze austriackim bieda i wzmagające się nastroje antyżydowskie prowadziły do powstania licznych ruchów nacjonalistycznych i syjonistycznych. Częsta była także emigracja, m.in. do Berlina, Francji czy też do Ameryki.

Po I wojnie światowej powstała niepodległa II Rzeczpospolita Polska. Żydzi stanowili w niej 9% ludności. Wraz z odrodzoną Polską powstawały w społeczności żydowskiej partie polityczne, będące odzwierciedleniem popularnych wśród ówczesnych Żydów ruchów ideologicznych: m.in. partie syjonistyczne, socjalistyczne, religijne, a także folkistowskie – pragnące zachować żydowską autonomię kulturalną. Jednocześnie polskie prawicowe partie polityczne otwarcie głosiły tezy antysemickie, które prowokowały rozruchy antyżydowskie i pogromy w okresie międzywojennym. Sytuacja Żydów uległa poprawie dopiero po zamachu stanu dokonanym przez Józefa Piłsudskiego (1926 r.) i dojściu do władzy sanacji. Po śmierci Piłsudskiego jednak sanacja musiała porozumieć się z obozami prawicowymi, co doprowadziło pod koniec lat 1930- tych do ponownego wzmożenia się prześladowań, w rezultacie czego np. na uniwersytetach wprowadzono tzw. getta ławkowe, które oddzielały studentów żydowskich od nieżydowskich lub ogłoszono bojkot żydowskich sklepów.

Odrestaurowany sklep spożywczy we Lwowie na Ukrainie. Szyldy napisane są w językach polskim, niemieckim i jidysz (2012), fot. Michael Hornsby.

W przeciągu kilku lat trwania II wojny światowej wymordowano większość europejskiego Żydostwa. Z 3,5 milionów polskich Żydów ocalało około 200-300 tysięcy. Blisko połowa z nich wyemigrowała z Polski w pierwszych latach powojennych. Po powstaniu państwa Izrael nastąpiła kolejna fala emigracji. Komunistyczne władze przez długi czas nie wydawały wiz wyjazdowych, w następstwie czego kolejne fale emigracji z Polski nastąpiły dopiero po 1956 r., wraz z liberalizacją praw emigracyjnych. Ostatnia fala emigracji została wywołana przez wydarzenia marca 1968 r., kiedy studenckie protesty przeciw ograniczeniom wolności i cenzurze PZPR zostały uznane przez władze za działania „V kolumny syjonistycznej”. Zapoczątkowało to wielką antysemicką nagonkę na mieszkających w Polsce Żydów - wielu zostało zwolnionych z pracy, wyrzuconych z PZPR. W okresie tym zmuszono do wyjazdu ok. 20 tysięcy Żydów. Obecnie w Polsce według danych ostatniego spisu powszechnego (2012 r.) żyje ok. 7 tysięcy Żydów.

Mitologia

Żydzi wybrali Polskę jako miejsce zamieszkania przede wszystkim z przyczyn pragmatycznych. Sytuacja polityczno-społeczna w XIII/XIV-wiecznym państwie polskim była dla nich korzystna i ułatwiła żydowskie osadnictwo na jego terenach [9] przyp09 / komentarz/comment /

przyp09 / komentarz/comment /

Por. np. przywileje wydawane Żydom przez polskich królów opisane w części „Krótki rys historyczny dotyczący historii Żydów w Polsce”. . Z krajem tym łączyli oni wielokrotnie swoje marzenia i nadzieje, które wyrażali między innymi w licznych legendach. Legitymizują one nie tylko obecność Żydów w Polsce, ale także opisują ich losy w tym kraju oraz przyjaze stosunki, które łączyły ich z Polakami i które mają swoje odbicie np. w legendzie o Esterce, kochance Kazimierza Wielkiego lub w opowieści o Saulu Wahlu, żydowskim królu Polski na jedną noc.

. Z krajem tym łączyli oni wielokrotnie swoje marzenia i nadzieje, które wyrażali między innymi w licznych legendach. Legitymizują one nie tylko obecność Żydów w Polsce, ale także opisują ich losy w tym kraju oraz przyjaze stosunki, które łączyły ich z Polakami i które mają swoje odbicie np. w legendzie o Esterce, kochance Kazimierza Wielkiego lub w opowieści o Saulu Wahlu, żydowskim królu Polski na jedną noc.

Istnieje kilka legend traktujących o początkach obecności Żydów w Polsce. Według jednej z nich lud Izraela, szargany nieszczęściami, szykanowany, prześladowany i przepędzany z miejsca na miejsce, zdecydował się wyruszyć w dalszą wędrówkę. Szukał dróg prowadzących do nowego kraju, który zapewni im spokój i szczęście. Nie wiedzieli jednak dokąd iść aż do momentu, kiedy z nieba spadła kartka. A na niej napisane było: „idźcie do Polski!”. Poszli więc do Polski, zaoferowali królowi górę złota, a ten przyjął ich z wdzięcznością i gościnnością. Inna legenda pokazuje Polskę jako kraj, w którym Żydzi mieszkali od dawien dawna. Opuszczając Królestwo Franków, natrafili pod Lublinem na Las Kawęczyński, w którym na każdym drzewie wisiała kartka z traktatem z Talmudu. Trzecia, najbardziej popularna legenda, wywodzi nazwę Polski z języka hebrajskiego. Gdy Żydzi przybyli na ziemie polskie, usłyszeć mieli głos mówiący do nich po hebrajsku: po-lin (hebr. פה-לין), co oznacza tu przenocuj. Dodatkowo w języku hebrajskim Polin (hebr. פולין) homonimicznie oznacza Polskę (Agnon 1916: 3-8) Agnon 1916: 3-8 / komentarz/comment/r /

Agnon 1916: 3-8 / komentarz/comment/r /

Agnon, Szmuel Josef 1916. "Polen. Die Legende von der Ankunft", w: Das Buch von den polnischen Juden, Berlin. .

.

| język hebrajski | transliteracja | transliteracja |

| פה-לין | po-lin | 'tu przenocuj' |

| פולין | Polin | 'Polska' |

Kazimierz Wielki był władcą, który rozszerzył przywileje nadane Żydom na teren całego rządzonego przez siebie kraju oraz był przychylnie nastawiony do Żydów przez okres swoich rządów. Niektórzy przyczyn tego dopatrują się w legendzie o Esterce. Żydówka Esterka miała być kolejną kochanką lub żoną Kazimierza Wielkiego, po Rokiczanie Praskiej oraz Adelajdzie Haskiej. Była niezwykle piękna i inteligentna, dała Kazimierzowi Wielkiemu dwie córki, które król pozwolił wychować w religii żydowskiej oraz dwóch synów - Niemierzę i Pełkę, którzy zostali oddani na wychowanie królowi i przyjęli wiarę chrześcijańską. Esterka często porównywana jest do biblijnej Estery, która wyszła za mąż za potężnego, pogańskiego króla Achaszwerosza i wstawiła się u swego męża za ludem Izraela, ocaliwszy go w ten sposób od pewnej śmierci. Sugeruje się przez to, że to ze względu na Esterkę król Kazimierz Wielki tak upodobał sobie polskich Żydów (Shmeruk 2000: 8-10)

Shmeruk 2000: 8-10 / komentarz/comment/r /

Shmeruk 2000: 8-10 / komentarz/comment/r / Shmeruk, Chone 2000. Legenda o Esterce w literaturze jidysz i polskiej. Warszawa: Oficyna Naukowa.

.

.Kolejna legenda dotyczy Saula Wahla, czyli właściwie Saula Katzenellenbogena, faktora królów Stefana Batorego i Zygmunta III Wazy, osobistego bankiera domu Radziwiłłów, syna rabina Samuela Katzenellenbogena z Padwy. Według podań Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł Czarny udał się na pielgrzymkę pokutną, pod koniec której znalazł się w Padwie, nie mając ani grosza przy duszy. Odmawiano mu pomocy, a wzmianki o jego książęcym pochodzeniu zbywano śmiechem i drwinami. Dopiero rabin Samuel Katzenellenbogen udzielił mu wsparcia i dał potrzebne środki na powrót do Polski. Po powrocie do Polski Mikołaj Radziwiłł odnalazł syna Samuela, Saula, który uczył się w jesziwie w Brześciu Litewskim. Będąc pod wrażeniem jego zdolności intelektualnych oraz wielkiej wiedzy, Radziwiłł zabrał Saula na swój dwór. Katzenellenbogen był tam bankierem oraz dzierżawcą ceł i warzelni soli. Wkrótce zdobył wielki majątek, a jego umiejętności docenił sam król Stefan Batory, który uczynił go swoim bankierem. Po śmierci Batorego w 1586 r. niezdecydowanie szlachty doprowadziło do podwójnej elekcji, w jej wyniku wybrani zostali Maksymilian Habsburg i Zygmunt III Waza; zaszła więc konieczność wyboru tymczasowego króla. Miał nim zostać Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł Czarny, ten jednak odmówił, sugerując, że królem powinien zostać ktoś bezstronny w sporze o tron, ktoś o wielkiej mądrości – zaproponował więc Saula Wahla. Ten przyjął tę godność i według legendy sprawował władzę przez jedną noc. W tym czasie wydał wiele nowych praw, między innymi przywileje dla ludności żydowskiej.

| ISO 639-3: | yid – kompleks jidysz |

| ydd – wschodni jidysz |

- "jidiš Varše" (Mojsze Zonszajn)

- Merke majn zun / מערקע מײַן זון

- "Mameszi" (Mordechaj Canin)

- "Jankele iz do ništ" (Mordechaj Canin)

- Kobi Weitzner

- Sonia Pinkusowicz-Dratwa

- Berešejs / Gen. 1,1-2

- Varše jidiš

- Haia Livri

- Šlof majn kind

- Hilda Bronstein

- Sonia Pinkusowicz-Dratwa (excerpt)

- Barry Davies

- Bella Kerridge

- Henryk Rajfer 1

- Henryk Rajfer 2

- Preliminary remarks

- WPŁYW JĘZYKÓW SŁOWIAŃSKICH NA JIDYSZ

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- przyp24

- przyp25

- przyp26

- przyp27

- przyp28

- przyp29

- przyp30

- przyp31

- przyp32

- przyp33

- przyp34

- przyp35

- przyp36

- przyp37

- przyp38

- przyp39

- przyp40

- przyp41

- przyp42

- przyp43

- przyp44

- przyp45

- przyp46

- przyp47

- ustawa w języku jidysz

- Agnon 1916: 3-8

- Shmeruk 2000: 8-10

- Geller 2008: 19

- Wexler 1991

- Katz 2005

- Geller 2001

- Pryłucki 1921

- Dyhr 1988

- Weinreich ( [1973] 2008)

- Geller 2001: 62

- Geller 2008: 685-686

- Jacobs 2005:70

- Birnbaum 1979: 41

- Brenzinger 2007: 2

- Birnbaum 1979

- Kondrat 2010: 62

- Fader 2009

- Katz 1983: 1019

- Barnavi i Charbit 1992: 193

- Katz 1983: 1020

- Katz 1983

- Katz 1983: 1021

- Weinreich 1959: 87

- Pryłucki 1917

- Jacobs 2005

- Geller 1994

- Katz 2007

- Seidman 2010

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- ilustr01

- ilustr02

- ilustr03

- ilustr04

- ilustr05

- ilustr06

- ilustr07

- ilustr08

- okres międzywojenny (IIRP)

- współczesność (IIRP)

- pomnik w jidysz w Dagdzie / Łatgalia

- mural jidysz w Lublinie

- Alfabet Jidysz

- okres przedrozbiorowy (IRP)

- Samogłoski języka jidysz

- Yiddish monophtong vowels