(Polish) Yiddish

Linguistic kinship and identity

Jewish languages

Yiddish is one example of many other Jewish languages that were spoken throughout the world by the Jewish diaspora. It would seem that a universal trend accompanied Jewish settlement when it comes to language: once living in a given country, the Jewish people would take its language and create their own variety which was similar to the local language to a certain degree. One of the features that was shared by all of these languages was that they were written using Hebrew script; borrowings were another. This way Jewish languages such as Ladino (Hispano-Jewish, Judeo-Espanyol), Judeo-Persian, Judeo-Arabic, etc.Language family, language branch

Yiddish is a mixed language created as a result of intensive and prolonged cultural and linguistic contact at the Germano-Slavic borderland which contains fused features from its determining languages (Hebrew-Aramaic, Slavic, German and a small Romance element).Affinity to:

- Polish,

- other majority languages,

- other minority languages.

There are two theories regarding the origins of the Yiddish language: the Germanocentric and Slavocentric theories. The first theory states that Yiddish belongs to the Germanic family, and more strictly to the West Germanic language branch along with: English, German, Frisian, Dutch and Africans. According to this theory, Yiddish was born in the 10th century in Lorraine with the Middle High German dialects as its basis. Although the emigration of Jews to Slavic territories led Yiddish to develop next to other Slavic languages it did not exercise a major influence on its structure.

The Germanocentric theory argues that Yiddish is Germanic not only genetically but also typologically. The theory additionally asserts that there is a developmental continuity between Western Yiddish, which was used by Jews of Western Europe and ceased to be spoken in the 19th century, and Eastern Yiddish used in East Europe. Under these assumptions, these two varieties of the Yiddish language should be treated as two dialects of the same language.

The Slavocentric theory, on the other hand, argues that "Yiddish is a mixed language created on a Slavic base (substratum) as a result of the language shift of an antecedent Jewish variety of a Slavic language into its Germanic counterpart" (Geller 2008:19

Geller 2008: 19 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2008: 19 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa & Monika Polit. 2008. Jidyszland - polskie przestrzenie. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

) The main proponent of this theory, the Israeli linguist Paul Wexler, in his publication Yiddish - the fifteenth Slavic language. A study of partial language shift from Judeo-Sorbian to German puts forward the thesis that the substratum of Yiddish was, in reality, a Judeo-Sorbian language (Wexler 1991

) The main proponent of this theory, the Israeli linguist Paul Wexler, in his publication Yiddish - the fifteenth Slavic language. A study of partial language shift from Judeo-Sorbian to German puts forward the thesis that the substratum of Yiddish was, in reality, a Judeo-Sorbian language (Wexler 1991 Wexler 1991 / komentarz/comment/r /

Wexler 1991 / komentarz/comment/r / Wexler, Paul. 1991. "Yiddish – The Fifteenth Slavic Language. A Study of Partial Language Shift from

Judeo-Sorbian to German", International Journal of the Sociology of Language 91.

). In contrast to the Germanocentric theory, Wexler's theory treats Western and Eastern Yiddish as two separate languages, with modern Yiddish being a developmental continuation of Eastern Yiddish.

). In contrast to the Germanocentric theory, Wexler's theory treats Western and Eastern Yiddish as two separate languages, with modern Yiddish being a developmental continuation of Eastern Yiddish.The mixed character of Yiddish can be exemplified by advanced synonymy. It is often the case that a specific idea can be described using a number of words originating from different source languages. As a result many borrowings gained specific, specialized and contextual meanings. Katz (2005

Katz 2005 / komentarz/comment/r /

Katz 2005 / komentarz/comment/r / Katz, Dovid 2005. The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. New Haven: Yale University.

) provides the example of the word gest טסעג (Ger. Gast "guest") which denotes any type of guest; orkhim (Hebr. חרואםיחרוא ) are usually 'poor visitors which ought to made guests during Sabbath or holidays'; whereas ushpizn (Aramaic ןיזיפשוא) are 'the seven biblical characters, from Abraham to David who, according to Jewish faith, visit Sukkahs during the Sukkot holidays'.

) provides the example of the word gest טסעג (Ger. Gast "guest") which denotes any type of guest; orkhim (Hebr. חרואםיחרוא ) are usually 'poor visitors which ought to made guests during Sabbath or holidays'; whereas ushpizn (Aramaic ןיזיפשוא) are 'the seven biblical characters, from Abraham to David who, according to Jewish faith, visit Sukkahs during the Sukkot holidays'.Yiddish and other Jewish languages also exhibit a number of shared features which emerged because of their role of binding the Jewish societies with Judaism. One feature is the way these languages have been written using Hebrew script, a sign of the religious identity its users adhered to. The Jewish languages, to a certain degree, possess a shared lexical base made of borrowings from Hebrew and Aramaic. Keeping in mind the importance of the Hebrew language to the Jewish societies, it becomes obvious that all of these languages had common kulturems - that is, the borrowings from Hebrew and Aramaic, the two sacred languages.

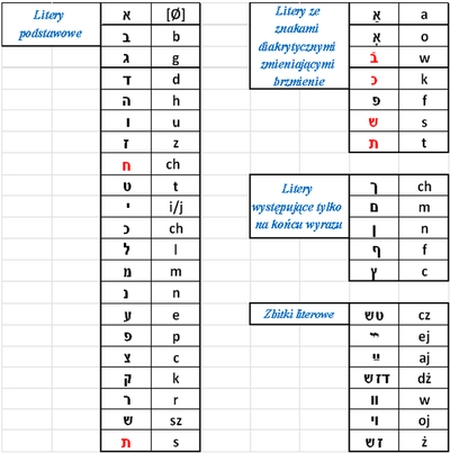

Yiddish alphabet (the letters marked in red are used solely in the Semitic loanwords)

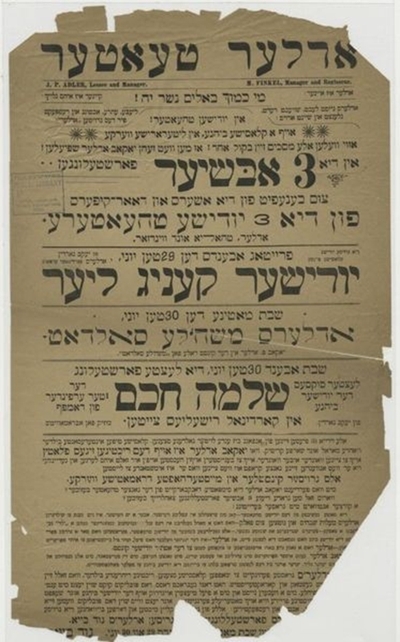

Yiddish written in Hebrew script: Poster of the play The Jewish King Lear.

The following partial translation comes from the webpage of the New York Public Library (NYLP):

Der Yudisher Kenig Lier [The Jewish King Lear] by

Mr Jacob Gordin

Mr Jacob Adler as King Lear,

Mr [Berl] Bernstein as Shammai

Windsor Theatre, Thursday, October 13, 1898.

'A sea of diamonds!'

'What, more diamonds?' we hear you say with a smirk. 'It must be some new play, but what of it'

'No, friend, this time you are wrong. We tell you in all seriousness that we have put together something the like of which you have never seen before, even in your dreams. Listen, now, to what we have for you: The Jewish King Lear, for the benefit of the Hebrew Legal Aid and Protective Association.'

NYPL Digital ID 435133.

The image is considered to be public ownership as its copyrights have expired. It concerns Australia, the European Union and other countries which recognize that copyrights expire after a minimum of 70 years after the author's death.Yiddish can be written using Latin alphabet; click hier to see a table compiled by YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research) showing one of the ways to transliterate Yiddish. Although standard Yiddish is widely recognized and accepted, from time to time one can see that it is ignored for the sake of certain words whose spelling is commonly known and used by Yiddish speakers. And so, in many American dictionaries the word chutzpah appears even though, according to YIVO, its correct transliteration should have the form of khutspe (in Polish transcription one should write 'chucpe').

Language or dialect? - as the speakers themselves see the issue

For a long time speakers of Yiddish (especially those connected to the Haskalah) considered their language to be nothing but a blend of various linguistic elements, a jargon with no rightful place, thus, denying it the autonomy and status of a separate language. It was not until the 20th century that due to the efforts of Yiddish scholars Yiddish was officially recognized as one of the national languages of East European Jewry (the second language was Hebrew - see the proceedings of the conference in Czerniowice, 1908. From a linguistic point of view, however, Yiddish is neither a dialect not a sociolect. By the advent of the II World War Yiddish was no worse than the other, so called, languages of culture.Identity - as the speakers themselves see the issue

- National and ethnic

- Religious

Yiddish, similarly to other Jewish languages, often borrowed from the loshn-koydesh (שדוק-ןושל) not only new words but also grammatical constructions. And vice versa, Yiddish had a great influence on the holy language, Hebrew, from the semantic calques present in texts written in this language.

Nowadays the speakers of Yiddish can be categorized into two groups: religious and secular.

The Holocaust caused many Jews to abandon Judaism and so their identity ceased to be connected with strictly religious. There are, however, Jewish communities which continue to cultivate Judaism and, along with it, the Yiddish language. The Hasidic Yiddish-Hebrew communities living in enclaves in the United States, Israel and in several European cities can exemplify the phenomenon of functional diglossia. Yiddish keeps serving the purpose of a language of everyday communication. Thus, these communities strive to separate this utilitarian language from the sacred language of liturgy.

- Biolects

Seidman 2010 / komentarz/comment/r /

Seidman 2010 / komentarz/comment/r / Seidman, Naomi 2010. "Małżeństwo z przeznaczenia", Cwiszn. Żydowski kwartalnik o literaturze i sztuce 3. online: http://www.cwiszn.pl/files/files/seidman_12-14_fragment.pdf [15.09.2012].

).

).Today in communities of Hasidic Jews Yiddish is used mainly by men. According to Fader, women are more prone to speak in the local language (in the examples analysed by Fader it is English). This language is, however, characterised by a large number of borrowings from Yiddish (Fader 2009

Fader 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Fader 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Fader, Ayala 2009. Mitzvah Girls. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

).

).Polish Yiddish

Dialectal classification of Yiddish

The dialectal classification of Yiddish was an object of linguistic enquiry since very early times. Even in the 17th century linguists were aware of the phonetic, morphological and lexical differences between the varieties of Yiddish spoken in German-speaking areas and territories where Slavic languages were spoken (Katz 1983: 1019 Katz 1983: 1019 / komentarz/comment/r /

Katz 1983: 1019 / komentarz/comment/r / Katz, Dovid 1983. „Zur Dialektologie des Jiddischen“, w: Werner Besch & Urlich Knoop & Wolfgang Putschke & Herbert Ernst Wiegand (red.) Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Berlin/Nowy Jork: Walter de Gruyter, s. 1018-1041.

). Today the term "Yiddish" addressed mainly the Eastern variety of the language and that is how it should be understood. For this reason the dialectal classification of Western Yiddish will be skipped.

). Today the term "Yiddish" addressed mainly the Eastern variety of the language and that is how it should be understood. For this reason the dialectal classification of Western Yiddish will be skipped.

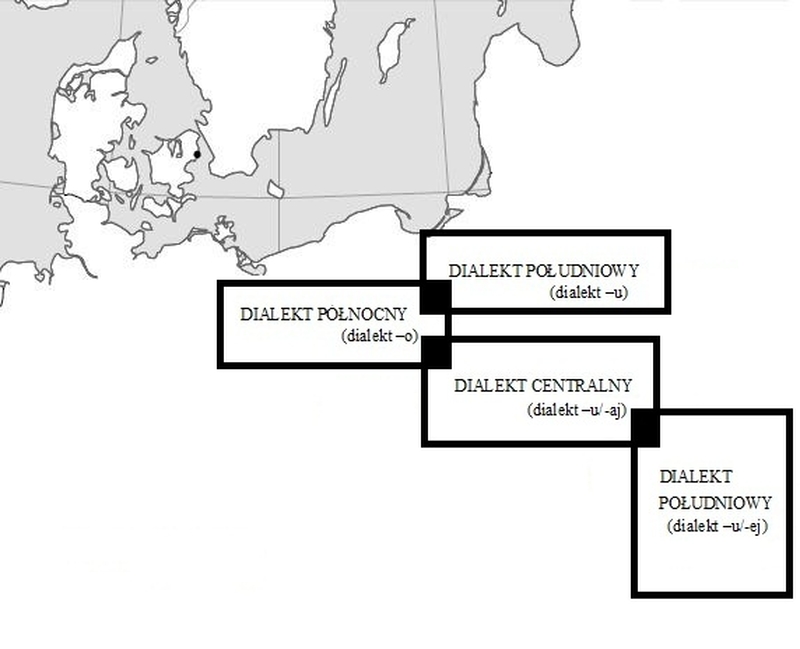

Map of Yiddish dialects (based on: Barnavi i Charbit 1992: 193

Barnavi i Charbit 1992: 193 / komentarz/comment/r /

Barnavi i Charbit 1992: 193 / komentarz/comment/r / Barnavi, Elie & Denis Charbit 1992. Histoire Universelle des Juifs. Paris: Hachette.

).

).A variety of criteria were considered when classifying the dialects of Yiddish. In 1913. Ber Borochov, regarded as the father of modern Yiddish Studies , took ethnic criteria as the centre of his research. He proposed that Yiddish should be divided into three dialects: Polish Yiddish, Southern Yiddish (used on the territories of Bukovina, Romania, Volhynia; also known as Ukrainian Yiddish), and Litvak Yiddish known also as Lithuanian (Katz 1983: 1020

Katz 1983: 1020 / komentarz/comment/r /

Katz 1983: 1020 / komentarz/comment/r / Katz, Dovid 1983. „Zur Dialektologie des Jiddischen“, w: Werner Besch & Urlich Knoop & Wolfgang Putschke & Herbert Ernst Wiegand (red.) Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Berlin/Nowy Jork: Walter de Gruyter, s. 1018-1041.

). It should be noted that these terms used should not be mistaken with country borders that exist now or, even, that existed in the past. They point more to languages inhabiting the same territory as the given dialect and influencing it linguistically: the Polish language influencing Polish Yiddish, Ukrainian - Southern Yiddish, Belarusian and Lithuanian - Litvak Yiddish. It is also worth stressing that when it comes to dialectal variation, the speakers of the dialects were, in turn, called: Polyakes "Poles" (,סעקַאילָאּפ), Galicianer "Galicians" (רענַאיצילַאג) and Litvakes ‘Lithuanians’ (סעקַאווטיל). This distinction was not purely linguistic but also addressed the way of thought and personalities of the Jews living in different parts of Eastern Europe.

). It should be noted that these terms used should not be mistaken with country borders that exist now or, even, that existed in the past. They point more to languages inhabiting the same territory as the given dialect and influencing it linguistically: the Polish language influencing Polish Yiddish, Ukrainian - Southern Yiddish, Belarusian and Lithuanian - Litvak Yiddish. It is also worth stressing that when it comes to dialectal variation, the speakers of the dialects were, in turn, called: Polyakes "Poles" (,סעקַאילָאּפ), Galicianer "Galicians" (רענַאיצילַאג) and Litvakes ‘Lithuanians’ (סעקַאווטיל). This distinction was not purely linguistic but also addressed the way of thought and personalities of the Jews living in different parts of Eastern Europe.The variation between the dialects stem mainly from the different realizations of stressed vowels. Salomon Birnbaum, having taken into consideration the phonetic criterion, divided Yiddish into the -o dialect (Litvak) and -u dialect (Polish and Southern). More specifically, the main criterion was the pronunciation of the vowel [o] as realized in Standard Yiddish words such as zogn ‘to say’ (ןגָאז), tog ‘day’ (גָאט); in the -u dialect pronounced as zugn, tug; and in the -o dialect as zogn, tog. Additionally Birnbaum divided the -u dialect further into two branches: the -ay dialect (Polish) and -ey dialect (Southern, Ukrainian). This division is substantiated by the phonetic realizations of the Standard Yiddish diphthong [ei] in such words as: meydl (לדיימ)‘girl’, zeyde (עדייז) ‘grandfather’, peysekh (חספ) ‘Pesach’; in the -ay dialect pronounced as maydl, zayde, paysekh; while in the -ey dialect it was realized as meydl, zeyde, peysekh.

Noakh Prilutski decided to examine how the dialects spread geographically and in 1920 he proposed a division into Central Yiddish and Eastern Yiddish. According to Prilutski, Central Yiddish encompassed the territory of Poland while Eastern Yiddish was used in what we know now as contemporary Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, Bessarabia, Volhynia and a part of Ukraine. The contributions of Prilutski to the field of Yiddish dialectology should be well noted. His Noyekh Prilutski zamlbikher far jidishn folklor, filologye un kultur-geshikhte (עטכישעג-וטלוק ןוא עיגָאלָאליֿפ,רָאלקלָאֿפןשידיי רַאֿפרעכיבלמַאזיקצולירּפחנ, Noah Prilutski's Anthology of Yiddish Folklore, Philology, and Cultural History) (1917

Pryłucki 1917 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pryłucki 1917 / komentarz/comment/r / Pryłucki, Nojech 1917. Nojech Prilutskis zamlbicher far jidiszn folklor, filologje un kultur-geszichte. Der konsonantizm. Warsze: Najer Farlag.

, 1921

, 1921 Pryłucki 1921 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pryłucki 1921 / komentarz/comment/r / Pryłucki, Nojech 1921. "Nojech Prilutskis zamlbicher far jidiszn folklor, filologje un kultur-geszichte", w: Dialektologisze paraleln un bamerkungen. Warsze: Najer Farlag.

Seidman, Naomi 2010. "Małżeństwo z przeznaczenia", Cwiszn 3. Available online at: http://www.cwiszn.pl/files/files/seidman_12-14_fragment.pdf (accessed 15 September 2012).

) is known as the first scholarly collection of folklore in Yiddish. Prilutski also accounted for the dialectal variation of the compiled materials. He is regarded as the scholar who laid the foundations of Yiddish dialectology with his study being a basic reference point for many other scholars for a very long time. Even today's division owes much to him. Katz (1983

) is known as the first scholarly collection of folklore in Yiddish. Prilutski also accounted for the dialectal variation of the compiled materials. He is regarded as the scholar who laid the foundations of Yiddish dialectology with his study being a basic reference point for many other scholars for a very long time. Even today's division owes much to him. Katz (1983 Katz 1983 / komentarz/comment/r /

Katz 1983 / komentarz/comment/r / Katz, Dovid. 1983. „Zur Dialektologie des Jiddischen“, w: Werner Besch & Urlich Knoop & Wolfgang Putschke & Herbert Ernst Wiegand (red.) Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Berlin/Nowy Jork: Walter de Gruyter, s. 1018-1041.

) quoted in his research but he simplified the terminology - for example, the dialect used primarily on the territory of the Kingdom of Poland was not called the Central Eastern Yiddish but simply Central Yiddish. The term Yiddish" here denotes the language of Eastern European Jews (and what Katz calles Eastern Yiddish) and not the language of the Western European Jewry (Western Yiddish).

) quoted in his research but he simplified the terminology - for example, the dialect used primarily on the territory of the Kingdom of Poland was not called the Central Eastern Yiddish but simply Central Yiddish. The term Yiddish" here denotes the language of Eastern European Jews (and what Katz calles Eastern Yiddish) and not the language of the Western European Jewry (Western Yiddish).Traditionally, Yiddish is divided into three dialects:

- North-Eastern (in Birnbaum's terminology - the -o dialect) which was used mainly in Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, North-Eastern Ukraine and North-Eastern Poland (in the area of Suwałki). The dialect is also known as the Litvak or Lithuanian dialect of Yiddish. It became the basis for the modern, standardised variety of the language which is now taught to those who wish to speak their heritage language and it is the language in which modern Yiddish literature is created and the press is published (it should be stressed, however, that not all of the features of the North-Eastern dialect were introduced into the standardised language);

- Central (in Birnbaum's terminology- the -ay dialect) which was spoken mainly on the territory of Congress Poland, Western and partially Eastern part of Galicia, in Northern and Eastern Hungary and, also, in Transylvania. Given the primary area where it was used - Poland - it is also known as the Polish dialect of Yiddish;

- South-Eastern (in Birnbaum's terminology the -ey dialect), often named Volhynian, Podolian or Bessarabian Yiddish. It was used on the territory of Ukraine, partially in Eastern Galicia, Romania and South-Eastern Poland.

Taking into consideration the number of phonetic features shared between the Central and South-Eastern dialects it became custom to describe them collectively as the Southern dialect (in contrast to the Northern dialect - Litvak Yiddish). The characteristic feature of the two dialects composing together the Southern dialect is the pronunciation of the proto-vowel [a:] as [u] (cf. zugn, tug). At the same time, of course, this main dialect can be divided into two smaller ones in which the proto-vowel[e1] is pronounced [ai] in the Polish dialect (cf. maydl "girl", zayde"grandfather") and in the Southern dialect as [ei] (cf. meydl, zeyde).

The phrase koyfn fleysh (שיילֿפןֿפיוק) "to buy meat", quoted often by dialectologists, sounds differently in each dialect:

keyfn fleysh in Northern Yiddish,

koyfn flaysh in Central Yiddish,

koyfn fleysh in Southern Yiddish.

A simplified division of Yiddish dialects can be presented as below:

It should be noted that the main differences between the dialects of Yiddish stem mainly from the different realizations of the given Yiddish proto-vowels. This is illustrated by the table below. For the sake of clarity and because Weinreich's proto-vowel system is not well known, these differences will be depicted with the point of reference being the modern, standard pronunciation of Yiddish vowels. Nevertheless, one should also keep in mind that there are other, morphological and lexical, differences between the dialects. With reference to Central Yiddish, its characteristics will be described further on separately.

Another fact to bear in mind is that, regardless of the specific dialects, the migration of people have always led to the overlapping and mixing of language varieties. Local dialects, as well, had its say in the development of Yiddish varieties. They often caused subdialects to emerge from the main dialects, subdialects characteristic for the given city, town or village.

| meaning | Northern Yiddish (–o dialect) | Central Yiddish (–u/-ay dialect) | Southern Yiddish (–u/-ey dialect) | Standard Yiddish |

| [aɪ̯] | [a:] | [a:] | [aɪ̯] | |

| mine | maɪ̯n | ma:n | ma:n | maɪ̯n |

| today | haɪ̯nt | ha:nt | ha:nt | haɪ̯nt |

| wine | vaɪ̯n | va:n | va:n | vaɪ̯n |

| [o] | [u] | [u] | [o] | |

| to say | zogn | zugn | zugn | zogn |

| Cracow | krokɛ | krukɛ | krukɛ | krokɛ |

| gift | matonɛ | matunɛ | matunɛ | matonɛ |

| [eɪ̯] | [oɪ̯] | [oɪ̯] | [oɪ̯] | |

| Torah | teɪ̯rɛ | toɪ̯rɛ | toɪ̯rɛ | toɪ̯rɛ |

| to live | veɪ̯nɛn | voɪ̯nɛn | voɪ̯nɛn | voɪ̯nɛn |

| to buy | keɪ̯fn | koɪ̯fn | koɪ̯fn | koɪ̯fn |

| [oɪ̯] | [o:] | [o:] | [oɪ̯] | |

| woman | froɪ̯ | fro: | fro: | froɪ̯ |

| windowpane | shoɪ̯b | sho:b | sho:b | shoɪ̯b |

| deaf (MASC./FEM.) | toɪ̯b | to:b | to:b | toɪ̯b |

| [ɛ] | [ei] | [ei] | [ɛ] | |

| to ask (please) | bɛtn | bejtn | bejtn | bɛtn |

| tavern | krɛchmɛ | kreychmɛ | kreychmɛ | krɛchmɛ |

| Zelig ’masculine name’ | zɛlik | zeylik | zeylik | zɛlik |

| [u] | [i] | [i] | [u] | |

| to come | kumɛn | kimɛn | kimɛn | kumɛn |

| room, chamber | shtub | shtib | shtib | shtub |

| to fret, to nag, to pester | muchɛn | michɛn | michɛn | muchɛn |

| [u] | [ɪ] | [ɪ] | [u] | |

| dog | hunt | hɪnt | hɪnt | hunt |

| Purim | purim | pɪrim | pɪrim | purim |

| [eɪ̯] | [aɪ̯] | [eɪ̯] | [eɪ̯] | |

| girl | meɪ̯dl | maɪ̯dl | meɪ̯dl | meɪ̯dl |

| Pesakh | peɪ̯sɛx | paɪ̯sɛx | peɪ̯sɛx | peɪ̯sɛx |

| grandfather | zeɪ̯dɛ | zaɪ̯dɛ | zeɪ̯dɛ | zeɪ̯dɛ |

Variation in the realizations of vowels in different dialects of Yiddish (examples based on the works: Geller 2001: 59

Geller 2001: 62 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2001: 62 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa 2001. Warschauer Jiddisch. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

and Katz 2007: 147-148

and Katz 2007: 147-148 Katz 2007 / komentarz/comment/r /

Katz 2007 / komentarz/comment/r / Katz, Dovid 2007. Words on Fire: The Unfinished Story of Yiddish. New York: Basic Books.

).

).Polish Yiddish

Polish Yiddish, also known as Central Yiddish, bordered with the North-Eastern dialect (Litvak; the border between the -u and -o dialects), with the South-Eastern dialect (Ukrainian; the border between the -ay and -ey dialects) and, in the South West, it bordered with the, so called, transitional Western dialects of Yiddish in Germany, the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Katz 1983: 1021 Katz 1983: 1021 / komentarz/comment/r /

Katz 1983: 1021 / komentarz/comment/r / Katz, Dovid 1983. „Zur Dialektologie des Jiddischen“, w: Werner Besch & Urlich Knoop & Wolfgang Putschke & Herbert Ernst Wiegand (red.) Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Berlin/Nowy Jork: Walter de Gruyter, s. 1018-1041.

).

).Polish Yiddish was not homogeneous. It comprised of many smaller subdialects typical for the given cities and towns. They differed from each other not only lexically but also, to some degree, phonetically. There were differences in the realization of vowels, diphthongs and, also, consonants - depending whether the sounds were uttered out in Warsaw, Sochaczew or in Lublin. That is why each of the subdialects of Polish Yiddish deserves its own research. Ewa Geller in her monograph Warschauer Jiddisch (2001

Geller 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa 2001. Warschauer Jiddisch. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

)) provided an in-depth and comprehensive work on one the largest subdialects of Central Yiddish - Warsaw Yiddish. Much valuable information on Polish Yiddish subdialects can be also found

)) provided an in-depth and comprehensive work on one the largest subdialects of Central Yiddish - Warsaw Yiddish. Much valuable information on Polish Yiddish subdialects can be also found in the aforementioned works of Noech Prilutski (1917

Pryłucki 1917 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pryłucki 1917 / komentarz/comment/r / Pryłucki, Nojech 1917. Nojech Prilutskis zamlbicher far jidiszn folklor, filologje un kultur-geszichte. Der konsonantizm. Warsze: Najer Farlag.

, 1921

, 1921 Pryłucki 1921 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pryłucki 1921 / komentarz/comment/r / Pryłucki, Nojech 1921. "Nojech Prilutskis zamlbicher far jidiszn folklor, filologje un kultur-geszichte", w: Dialektologisze paraleln un bamerkungen. Warsze: Najer Farlag.

Seidman, Naomi 2010. "Małżeństwo z przeznaczenia", Cwiszn 3. Available online at: http://www.cwiszn.pl/files/files/seidman_12-14_fragment.pdf (accessed 15 September 2012).

) known under the title Noyekh Prilutski zamlbikher far jidishn folklor, filologye un kultur-geshikhte (עטכישעג-רוטלוקןוא עיגָאלָאליֿפ,רָאלקלָאֿפןשידיי רַאֿפרעכיבלמַאזיקצולירּפחנ). There is also a study on Lublin Yiddish (Lubliner Jiddisch by Mogens Dyhr & Ingeborg Zint. 1988). The following analysis of the features of Central Yiddish is based mainly on the research of Prilutski (1917

) known under the title Noyekh Prilutski zamlbikher far jidishn folklor, filologye un kultur-geshikhte (עטכישעג-רוטלוקןוא עיגָאלָאליֿפ,רָאלקלָאֿפןשידיי רַאֿפרעכיבלמַאזיקצולירּפחנ). There is also a study on Lublin Yiddish (Lubliner Jiddisch by Mogens Dyhr & Ingeborg Zint. 1988). The following analysis of the features of Central Yiddish is based mainly on the research of Prilutski (1917 Pryłucki 1917 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pryłucki 1917 / komentarz/comment/r / Pryłucki, Nojech 1917. Nojech Prilutskis zamlbicher far jidiszn folklor, filologje un kultur-geszichte. Der konsonantizm. Warsze: Najer Farlag.

, 1921

, 1921 Pryłucki 1921 / komentarz/comment/r /

Pryłucki 1921 / komentarz/comment/r / Pryłucki, Nojech 1921. "Nojech Prilutskis zamlbicher far jidiszn folklor, filologje un kultur-geszichte", w: Dialektologisze paraleln un bamerkungen. Warsze: Najer Farlag.

Seidman, Naomi 2010. "Małżeństwo z przeznaczenia", Cwiszn 3. Available online at: http://www.cwiszn.pl/files/files/seidman_12-14_fragment.pdf (accessed 15 September 2012).

) and Geller (2001

) and Geller (2001 Geller 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa 2001. Warschauer Jiddisch. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

).

).Vowel system of Polish Yiddish

As Weinreich stresses (1973; 2008:15 Weinreich ( [1973] 2008) / komentarz/comment/r /

Weinreich ( [1973] 2008) / komentarz/comment/r / Weinreich, Max (1973) 2008. History of the Yiddish Language. Nowy Jork: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (Tytuł oryg. Geszichte fun der jidiszer szprach, przeł. Shlomo Noble, red. Paul Glaser).

), the difference between the dialects focus mainly on the articulation of vowels and diphthongs. One of the characteristic features of Central Yiddish is the presence of long and short vowels. Although scholars recognize the existence of a short vowel : long vowels opposition, a portion of these sounds are not contained words which differ only in one vowel sounds, also known as minimal pairs (Geller 2001: 62

), the difference between the dialects focus mainly on the articulation of vowels and diphthongs. One of the characteristic features of Central Yiddish is the presence of long and short vowels. Although scholars recognize the existence of a short vowel : long vowels opposition, a portion of these sounds are not contained words which differ only in one vowel sounds, also known as minimal pairs (Geller 2001: 62 Geller 2001: 62 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2001: 62 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa 2001. Warschauer Jiddisch. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

). Traditionally, three sets of short and long vowels can be listed. [a] : [a:]; [i] : [i:] and [ᴐ:] : [ᴐu]. The vowel system of Central Yiddish is shown below (see: Geller 2001: 62

). Traditionally, three sets of short and long vowels can be listed. [a] : [a:]; [i] : [i:] and [ᴐ:] : [ᴐu]. The vowel system of Central Yiddish is shown below (see: Geller 2001: 62 Geller 2001: 62 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2001: 62 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa 2001. Warschauer Jiddisch. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

):

):| i: i | u | |||

| ɛɪ̯ | ɔ: / ɔu | |||

| ɛ | ɔ | ɔɪ̯ | ||

| a | ||||

| a: | ||||

| aɪ̯ |

The characteristic features of the vowel system of Central Yiddish will be illustrated by a sentence quoted by Weinreich ([1973] 2008: 15

Weinreich ( [1973] 2008) / komentarz/comment/r /

Weinreich ( [1973] 2008) / komentarz/comment/r / Weinreich, Max (1973) 2008. History of the Yiddish Language. Nowy Jork: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (Tytuł oryg. Geszichte fun der jidiszer szprach, przeł. Shlomo Noble, red. Paul Glaser).

) , in today standard Yiddish pronounced as du zogst hajnt nejn [du zokst haɪ̯nt neɪ̯n] ‘today you say "no"’, while in Central Yiddish it is:

) , in today standard Yiddish pronounced as du zogst hajnt nejn [du zokst haɪ̯nt neɪ̯n] ‘today you say "no"’, while in Central Yiddish it is: - di zugst hant najn [di: zukst ha:nt naɪ̯n]: Yid. stand. [u] → Yid. cent. [i:], e.g. [du] : [di:] ‘you’, [gut] : [gi:t] ‘good’, [bruder] : [bri:der] ‘brother’;

- Yid. stand. [ɔ] → Yid. cent. [u], e.g. [zɔgņ] : [zugņ] ‘to say’, [tɔk] : [tuk] ‘day’, [jɔr] : [jur] ‘year’ – this feature discerns the Polish and Ukrainian Yiddish from Litvak Yiddish;

- Yid. stand. [aɪ̯] → Yid. cent. [a:], e.g. [haɪ̯nt] : [ha:nt] ‘today’, [t͡saɪ̯t] : [t͡sa:t] ‘time’, [vaɪ̯p] : [va:p] ‘wife’;

- Yid. stand. [eɪ̯] → Yid. cent. [aɪ̯], e.g. [neɪ̯n] : [naɪ̯n] ‘no’, [meɪ̯dl] : [maɪ̯dl] ‘girl’, [geɪ̯ņ] : [gaɪ̯ņ] ‘to go’ – this feature discerns Polish Yiddish from Ukrainian Yiddish;

- Yid. stand. [ɔʏ̯] → Yid. cent. [ɔ:], e.g. [bɔʏ̯x] : [box] ‘stomach, belly’, [tɔʏ̯b] : [to:b] ‘dove’, [tɔʏ̯znt] : [to:znt] ‘thousand’;

- Yid. stand. stressed [ɛ] → Yid. cent. [eɪ̯] in an open syllable, e.g. [rɛgn] : [reɪ̯gn] ‘rain’, [lɛder] : [leɪ̯der] ‘skin’, [lɛbm]: [leɪ̯bm] ‘to live’;

- Yid.stand. the standard diminituve plural suffix -e/lekh in Central Yiddish takes the form of -aɫax, e.g. Yid. stand. [mejdelex] - yid. cent. [majdaɫax] ‘little girls’.

| meaning | Standard Yiddish | Polish Yiddish |

| [u] | [i:] | |

| you | du | di: |

| good | gut | gi:t |

| brother | bruder | bri:der |

| [ɔ] | [u]* | |

| to say | zɔgn | zugn |

| day | tɔk | tuk |

| year | jɔr | jur |

| [aɪ̯] | [a:] | |

| today | haɪ̯nt | ha:nt |

| time | t͡saɪ̯t | t͡sa:t |

| wife | vaɪ̯p | va:p |

| [eɪ̯] | [aɪ̯]** | |

| no | neɪ̯n | naɪ̯n |

| girl | meɪ̯dl | maɪ̯dl |

| go | geɪ̯ņ | gaɪ̯ņ |

| [ɔʏ̯] | [ɔ:] | |

| stomach, belly | bɔʏ̯x | bɔ:x |

| dove | tɔʏ̯b | tɔ:b |

| thousand | tɔʏ̯znt | tɔ:znt |

| [ɛ] | [eɪ̯]*** | |

| rain | rɛgn | reɪ̯gn |

| skin | lɛder | leɪ̯der |

| to live | lɛbm | leɪ̯bm |

| [-(e)lex] | [-aɫax]**** | |

| girls | mejdelex | majdaɫax |

* - this feature separates the Polish and Ukrainian dialects from the Litvak dialect

** - this feature separates Polish Yiddish and Litvak Yiddish from Ukrainian Yiddish

*** - in an open syllable

**** - a standard diminutive suffix

Consonant system

As said previously, the differences between the consonantal systems of the dialects were not great enough to base dialectological research on them. Nonetheless, there was a number of features that were characteristic for Central Yiddish:- in many cases the final-positioned voiced plosives become unvoiced, e.g. hobm ‘to have’– [ɛjx hop] ‘I have’; zugn ‘to say’ – [ɛjx zuk] ‘I am saying’; rɛdn ‘to say’ – [ɛjx rɛt] ‘I am saying’;

- [l] is palatalised after [k] and [g], e.g. [kl’apm] ‘to clap’; [gl’ik] ‘happiness’;

- frequently, the fricative [h] undergoes elision, e.g. Yid.stand. [hundert] ‘hundred’– Yid.cent. [ɨndert]; Yid.stand. [got helft] ‘God will help’ – Yid.centr. [gᴐt ɛlft]; Yid.stand. [gehat] - future participle of hobm ‘have’ – Yid. centr. [gɛat].

Morphology

The distinctive feature of Central Yiddish morphology is that the standard personal pronoun mir (1 Pl.) is replaced by ints [jint͡s] while the standard personal pronoun ir (2 Pl.) is replaced by ets [ɛt͡s], which, in turn, in the genitive case changes to enk [ɛɳk] (in Standard Yiddish ayx) with its possessive form ‘your’ being enker [ɛɳkɛr] (instead of the standard Yiddish ayer). A characteristic 2 Pl. imperative form can also be formed by adding the suffix -c to the root of the verb, e.g. gajc! instead of the standard form gejt ‘(you all) go!’ or laxts! '(you all) laugh!' instead of the standard lacht!Another feature of Central Yiddish is the merging of the disjunctive 3 Sg. masculine personal pronoun in the oblique case (any case except the nominative) [ɛjm] ‘him, to him, with him’ (in Standard Yiddish im) with the preceding preposition, e.g. mitn ‘with him’, in contrast to the Standard Yiddish mit im.

Now it is a good time to describe the system of disjunctive and conjunctive personal pronouns and their short forms - which is characteristic for Central Yiddish. Short and long forms of personal pronouns existed in each dialect of Yiddish (the pronouns differed mainly in pronunciation and, also, in the fact that Central Yiddish used the forms quoted above). In modern Standard Yiddish only two disjunctive forms are used: ix > x’ ‘me’ [e.g. x’vel ajx zogn < > Yid. centr. x’vel-ax zugn] and es > s’, impersonal pronoun ‘it’, [e.g. s’iz geven < > Yid. cent. s’i gieven].

Forms of pronouns typical for Central Yiddish (see Geller 2008: 685-686

Geller 2008: 685-686 / komentarz/comment/r /

Geller 2008: 685-686 / komentarz/comment/r / Geller, Ewa 2008. „Germanocentric vs. Slavocentric Approach to Yiddish”, w: Vom Wort zum Text. Studien zur Deutschen Sprache und Kultur. Festschrift für Professor Józef Wiktorowicz zum 65. Geburtstag. Warszawa: Instytut Germanistyki, s. 681-693.

):

):| meaning | disjunctive pronouns | conjunctive pronouns | standard Yiddish |

| I | x-, ɛx | ɛyx, iyɛx, yax | ix |

| you | tɨ | di: | du |

| he | ɛ(r), r- | ɛyɛ | er |

| she | zi, z- | zi: | zi |

| it | s-, sɛ, sɨ | ɛs | es |

| we | ɨnts, mɛ, ma | yint͡s/miyɛ | mir |

| you | -ts | ɛts | ir |

| them | zɛ, z- | zay | zey |

The system of disjunctive and conjunctive personal pronouns in Central Yiddish

Central Yiddish uses a special grammatical construction to express the present tense for the first person plural. Two personal pronouns are used in a tautological manner - the long, conjunctive form is placed before the noun while the short, disjunctive form is added to the noun's root: ints [jints]+ verb's root + mǝ, ints geymǝ (in Standard Yiddish mir gejen), compare Polish translation: ‘my idziemy’; ints zugmǝ (in Standard Yiddishmir zogn) compare Polish: ‘my mówimy’; It would seem, thus, that this construction should be explained by the influence of the Polish language on Yiddish. Colloquial German constructions such as gemma! (Jacobs 2005: 70 Jacobs 2005:70 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jacobs 2005:70 / komentarz/comment/r / Jacobs, Neil G. 2005. Yiddish: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: CUP.

) are used in German and Austrian German only in the imperative. In Yiddish, as in Polish, these forms are not limited only to the imperative form but also to the indicative.

) are used in German and Austrian German only in the imperative. In Yiddish, as in Polish, these forms are not limited only to the imperative form but also to the indicative.Lexis

The lexical differences between the Central, North-Eastern and South-Eastern dialects of Yiddish can be exemplified by the well-known terms for "shop" in each of these dialects. For the speaker of Polish Yiddish it is gevelb (בלעוועג), for a Litvak kleyt (טיילק), while for an Ukrainian Jew a "shop" would be krom (םָארק).It should be noted that these differences in the lexicon of these dialects stem mainly from the influence of the local, non-Jewish majorities and their languages. It comes as no surprise, then, that Central Yiddish was abundant in Polish language borrowings, e.g. kaviarnye (עינרַאיווַאק) ‘kawiarnia’ (cafe), mentlik (קילטנעמ) ‘mętlik’ (confusion), kajzerke (עקרעזַײק) ‘kajzerka’ (a type of bread roll), ulik (קילוא) ‘ulik’ (a type of herring), subyekt (טקעיבוס) ‘subjekt, sprzedawca’ (shop assistant), stenken (ןעקנעטס) ‘stękać’ (to groan, moan, grunt), polevke (עקוועלָאּפ) ‘polewka’ (a soup), fundirn (ןרידנוֿפ) ‘fundować’ (to buy, to found, to endow), flondre (ערדנָאלֿפ) ‘flądra’ (a pejorative term describing a woman; trollop, slattern), and many others.

There was almost 3 million Yiddish speakers in pre-WW2 Poland (Birnbaum 1979: 41

Birnbaum 1979: 41 / komentarz/comment/r /

Birnbaum 1979: 41 / komentarz/comment/r / Birnbaum, Salmo 1979. Yiddish: A survey and a grammar. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

). In modern Poland only a handful of native Yiddish speakers have lived on. Native Yiddish speakers can be much easily spotted in centres of Jewish culture such as London or New York. It is a well established fact, however, that the Yiddish language is endangered (Brenzinger 2007: 2

). In modern Poland only a handful of native Yiddish speakers have lived on. Native Yiddish speakers can be much easily spotted in centres of Jewish culture such as London or New York. It is a well established fact, however, that the Yiddish language is endangered (Brenzinger 2007: 2 Brenzinger 2007: 2 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brenzinger 2007: 2 / komentarz/comment/r / Brenzinger, Matthias (ed.) 2007. Language diversity endangered. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

). This is why there are undergoing efforts to research and document its linguistic features (compare Birnbaum 1979

). This is why there are undergoing efforts to research and document its linguistic features (compare Birnbaum 1979 Birnbaum 1979 / komentarz/comment/r /

Birnbaum 1979 / komentarz/comment/r / Birnbaum, Salmo 1979. Yiddish: A survey and a grammar. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

; Jacobs 2005

; Jacobs 2005 Jacobs 2005 / komentarz/comment/r /

Jacobs 2005 / komentarz/comment/r / Jacobs, Neil G. 2005. Yiddish: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: CUP.

). The Polish dialect of Yiddish is also endangered because of the revitalization of Yiddish itself - which, obviously, is connected to the efforts of creating a "standard language". Although Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Latvia and Lithuania put together were inhabited by a smaller number of Yiddish speakers than Poland on its own, and that it was only the USSR had a comparable number of Jews on its territory, the decision of YIVO remained unchanged. YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research in New York, Yid. Yidisher Wisnshaftlekher Institut, YIVO, with its main base of operation in Vilnius up until the advent of the WW2) was an academic institute which partook in the standardisation of the Yiddish language. By its decision it was the Northern Yiddish dialect, spoken in Latvia and Lithuania, that was used as the basis for today's Standard Yiddish - now taught on summer schools and used in course books all over the world.

). The Polish dialect of Yiddish is also endangered because of the revitalization of Yiddish itself - which, obviously, is connected to the efforts of creating a "standard language". Although Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Latvia and Lithuania put together were inhabited by a smaller number of Yiddish speakers than Poland on its own, and that it was only the USSR had a comparable number of Jews on its territory, the decision of YIVO remained unchanged. YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research in New York, Yid. Yidisher Wisnshaftlekher Institut, YIVO, with its main base of operation in Vilnius up until the advent of the WW2) was an academic institute which partook in the standardisation of the Yiddish language. By its decision it was the Northern Yiddish dialect, spoken in Latvia and Lithuania, that was used as the basis for today's Standard Yiddish - now taught on summer schools and used in course books all over the world. ISO Code

| ISO 639-3: | yid – Yiddish |

| yid – Eastern Yiddish |

- "jidiš Varše" (Mojsze Zonszajn)

- Merke majn zun / מערקע מײַן זון

- "Mameszi" (Mordechaj Canin)

- "Jankele iz do ništ" (Mordechaj Canin)

- Kobi Weitzner

- Sonia Pinkusowicz-Dratwa

- Berešejs / Gen. 1,1-2

- Varše jidiš

- Haia Livri

- Šlof majn kind

- Hilda Bronstein

- Sonia Pinkusowicz-Dratwa (excerpt)

- Barry Davies

- Bella Kerridge

- Henryk Rajfer 1

- Henryk Rajfer 2

- Preliminary remarks

- WPŁYW JĘZYKÓW SŁOWIAŃSKICH NA JIDYSZ

- przyp01

- przyp02

- przyp03

- przyp04

- przyp05

- przyp06

- przyp07

- przyp08

- przyp09

- przyp10

- przyp11

- przyp12

- przyp13

- przyp14

- przyp15

- przyp16

- przyp17

- przyp18

- przyp19

- przyp20

- przyp21

- przyp22

- przyp23

- przyp24

- przyp25

- przyp26

- przyp27

- przyp28

- przyp29

- przyp30

- przyp31

- przyp32

- przyp33

- przyp34

- przyp35

- przyp36

- przyp37

- przyp38

- przyp39

- przyp40

- przyp41

- przyp42

- przyp43

- przyp44

- przyp45

- przyp46

- przyp47

- ustawa w języku jidysz

- Agnon 1916: 3-8

- Shmeruk 2000: 8-10

- Geller 2008: 19

- Wexler 1991

- Katz 2005

- Geller 2001

- Pryłucki 1921

- Dyhr 1988

- Weinreich ( [1973] 2008)

- Geller 2001: 62

- Geller 2008: 685-686

- Jacobs 2005:70

- Birnbaum 1979: 41

- Brenzinger 2007: 2

- Birnbaum 1979

- Kondrat 2010: 62

- Fader 2009

- Katz 1983: 1019

- Barnavi i Charbit 1992: 193

- Katz 1983: 1020

- Katz 1983

- Katz 1983: 1021

- Weinreich 1959: 87

- Pryłucki 1917

- Jacobs 2005

- Geller 1994

- Katz 2007

- Seidman 2010

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- ilustr01

- ilustr02

- ilustr03

- ilustr04

- ilustr05

- ilustr06

- ilustr07

- ilustr08

- okres międzywojenny (IIRP)

- współczesność (IIRP)

- pomnik w jidysz w Dagdzie / Łatgalia

- mural jidysz w Lublinie

- Alfabet Jidysz

- okres przedrozbiorowy (IRP)

- Samogłoski języka jidysz

- Yiddish monophtong vowels