Latgalian

Genetic and typological classification

Genetic classification

The Latgalian language is a member of a group of languages called Eastern Baltic languages, along with Latvian and Lithuanian. Baltic languages make up one of the groups which together form the Indo-European language family. Latgalian, as a separate dialect, originated from Baltic dialects during the medieval times.Latgalian differs from the standard Latvian in its specific lexical, phonological and grammatical features. The following table presents comparison of Our Father in standard Latvian and Latgalian.

Table Our Father prayer in Latvian and Latgalian. (source: Andronov & Andronova 2009: 68

Andronov & Andronova 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Andronov & Andronova 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Andronov, Aleksey & Everita Andronova 2009. „The Latgalian Component in the Latvian National Corpus”, w: V. Lyding (red.) Proceedings of the Second Colloqium on Lesser Used Languages and Computer Linguistics. Bolzano: Accademia Europea. 65–77.

)

)| Latvian | Latgalian |

| Mūsu Tēvs debesīs! Svētīts lai top Tavs vārds. Lai nāk Tava valstība. Tavs prāts lai notiek kā debesīs, tā arī virs zemes. Mūsu dienišķo maizi dod mums šodien. Un piedod mums mūsu parādus, Kā arī mēs piedodam saviem parādniekiem. Un neieved mūs kārdināšanā. Bet atpestī mūs no ļauna. [Jo Tev pieder valstība, spēks un gods mūžīgi mūžos.] Āmen. | Tāvs myusu, kas esi debesīs, svieteits lai tūp Tovs vuords,lai atīt Tova vaļsteiba, Tova vaļa lai nūteik kai debesīs, tai ari viers zemis. Myusu dīniškū maizi dūd mums šudiņ un atlaid mums myusu poruodus, kai ari mes atlaižam sovim poruodnīkim, un naīved myusu kārdynuošonā, bet atpestej myus nu ļauna. Amen. |

Phonetically, Latgalian resembles the Lithuanian language more closely than it resembles a typical Latvian dialect (Brejdak 2006: 195

Brejdak 2006 / komentarz/comment/r /

Brejdak 2006 / komentarz/comment/r / Brejdak, A. 2006. „Łatgal’skij jazyk”, w: Jazyki mira: Baltijskie jazyki. Moskwa: Akademia. 193–213.

). In Lower-Latvian dialects and the Latvian literary language there are no palatalized consonants, which are characteristic of Latgalian and Lithuanian. Another difference between Upper-Latvian/Latgalian and Lower-Latvian concerns tones, or so-called “intonation patterns” of Baltic languages. In Upper-Latvian the intonation happens to be indicative, which is not really considered a tone in a phonological sense (Balode & Holvoet 2001: 15

). In Lower-Latvian dialects and the Latvian literary language there are no palatalized consonants, which are characteristic of Latgalian and Lithuanian. Another difference between Upper-Latvian/Latgalian and Lower-Latvian concerns tones, or so-called “intonation patterns” of Baltic languages. In Upper-Latvian the intonation happens to be indicative, which is not really considered a tone in a phonological sense (Balode & Holvoet 2001: 15 Balode & Holvoet 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Balode & Holvoet 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Balode, Laimute & Axel Holvoet 2001. „The Latvian language and its dialects”, w: Ö. Dahl & M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (red.) Circum-Baltic Languages. vol.1. Past and Present. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 3–40.

).

).Differences between Latgalian and standard Latvian language also appear in vocabulary. In Latgalian, for instance, there are exponents of modality, such as može ‘maybe’, mušeņ or mošeņ ‘probably’, expressing deduced certainty (compare: Polish dialectal musi ‘certainly’), which are absent in Latvian (Nau 2012: 487

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2012. “Modality in an areal context: the case of a Latgalian dialect”, w: B. Wiemer i in. (red.) Grammatical replication and borrowability in language contact. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 465–508.

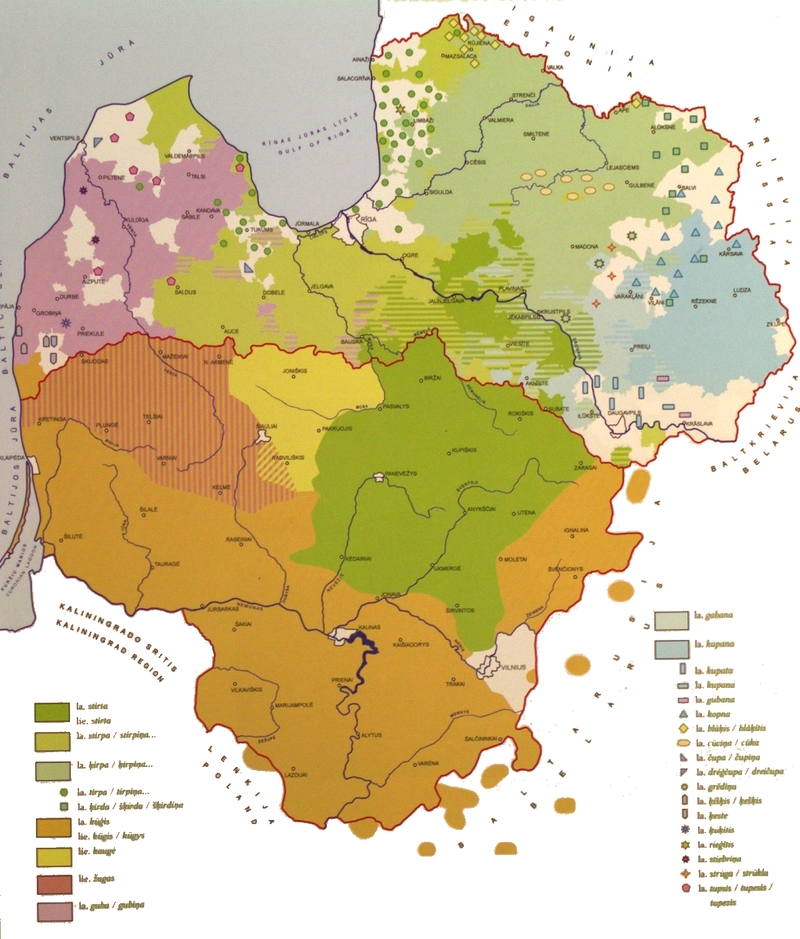

). The following illustration presents dialectal diversity among Baltic languages using the word ‘(hay)stack’ as an example. Latgalian variants are marked in blue.

). The following illustration presents dialectal diversity among Baltic languages using the word ‘(hay)stack’ as an example. Latgalian variants are marked in blue.

‘(hay)stack’ in Baltic languages (source: Baltu valodu atlants 2009: 161

Atlas Języków Bałtyckich 2009 / komentarz/comment/r /

Atlas Języków Bałtyckich 2009 / komentarz/comment/r / Baltu valodu atlants ['Atlas języków bałtyckich'] 2009. Rīga-Vilnius: Latvijas Universitāte.

)

)Typological classification

The default syntax of a basic sentence in Latgalian is SVO (subject – verb – object, like Grace is eating a doughnut). Nevertheless, a Latgalian sentence, like a Polish one, has quite an informal word order. That means the order of words in a sentence is based on pragmatic factors – for example, an intention to put an emphasis on a certain piece of information in a message – rather than grammatical.Grammatically, the Latgalian language resembles Polish in many ways. It is an inflectional language, in which grammatical categories, like number or gender, are expressed by various suffixes. Inflection of the Latgalian language means that one suffix can bear more than one piece of grammatical information at once. For example, the grammatical suffix – ūs in a word vacūs ‘old’ conveys four grammatical meanings: accusative case, plural, masculine gender and definiteness.

As in Polish, Latgalian has seven grammatical cases, including the vocative:

| M. | bruoļs | ‘brat’ |

| D. | bruoļa | ‘brata’ |

| C. | bruoļam | ‘bratu’ |

| B. | bruoli | ‘brata’ |

| N. | bruoli | ‘bratem’ |

| Msc. | bruolī | ‘bracie’ |

| W. | bruoļ! | ‘bracie!’ |

Latgalian is abundant in dimunitives (e. g. mads ‘honey’ > medens ‘a little bit of honey’).

Adjectival endings in Latgalian not only provide information about gender, number and case, but also about definiteness/indefiniteness (meaning comparable to that of the/a in English):

lob-s teksts ‘a good text’

lob-ys teksts ‘the good text’

Past and present tense forms of verbs in Latgalian are created mainly from different stems, whereas in order to create a future tense form it is required to add a suffix. Third person singular and plural forms are identical. The following table presents the most important verbal forms on an example of a verb meklēt ‘to seek’. In the third person there is no difference between numbers - jis meklej ‘he searches’, jī meklej ‘they search’. A set of stems used to create some of the verbal forms is presented in the following table using the verb meklēt ‘to search’ as an example.

| I stem | II stem | III stem | |

| infinitival forms | meklē-t INFINITIVE maklā-tu SUPINUM | ||

| tense 1 per. sing. 2 per. sing. 3 per. 1 per. pl. 2 per. pl. | PRESENT TENSE meklej-u meklej meklej meklej-am meklej-at | PAST TENSE mekliej-u mekliej-i meklēj-a mekliej-om mekliej-ot | FUTURE TENSE mekliej-š-u mekliej-s-i meklē-s meklē-s-im meklē-s-it |

| mood | meklej-it IMPERATIVE MOOD FOR 2 PER. PL | maklā-tu CONDITIONAL MOOD |

A curious phonological trait of Latgalian is morphonological harmony: within one word form there has to be either palatalized consonants (not marked in written form) and front vowels or unpalatalized consonants and back vowels. Latgalian words tend to comply with this rule (Nau 2011: 9

Nau 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2011. A short grammar of Latgalian. München: Lincom Europa.

). Compare the two tables: the infinitive meklēt [mʲɛʲklʲɛːtʲ] and supinum maklātu [maklaːtu].

). Compare the two tables: the infinitive meklēt [mʲɛʲklʲɛːtʲ] and supinum maklātu [maklaːtu].Influence of other languages on Latgalian

Latgale had always been a multilingual region and it has stayed that way to this day. Back in the Medieval times it was an area of interactions between the Baltic dialects and the Balto-Finnish dialects – especially those which gave rise to languages such as Livonian and Estonian (Nau 2012: 473 Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2012. “Modality in an areal context: the case of a Latgalian dialect”, w: B. Wiemer i in. (red.) Grammatical replication and borrowability in language contact. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 465–508.

) – and also between Lower-German, whose influence on Latgalian lasted up to 16th c. Period from 1629 up to 19th c. was mainly a time of domination of the Polish language. In 19th and 20th centuries it was the Russian language which had most influence on Latgalian. Latgalian also had contact with Lithuanian and Belarussian in the borderlands, as well as Yiddish: in 19th c. about half of the people living in cities of Dyneburg, Rēzekne and Ludzy were Jews (Nau 2012: 474

) – and also between Lower-German, whose influence on Latgalian lasted up to 16th c. Period from 1629 up to 19th c. was mainly a time of domination of the Polish language. In 19th and 20th centuries it was the Russian language which had most influence on Latgalian. Latgalian also had contact with Lithuanian and Belarussian in the borderlands, as well as Yiddish: in 19th c. about half of the people living in cities of Dyneburg, Rēzekne and Ludzy were Jews (Nau 2012: 474 Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2012. “Modality in an areal context: the case of a Latgalian dialect”, w: B. Wiemer i in. (red.) Grammatical replication and borrowability in language contact. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 465–508.

). After Latvia gained independence, it was Latvian which had the biggest impact on Latgalian.

). After Latvia gained independence, it was Latvian which had the biggest impact on Latgalian.Borrowings from before the period of literary texts began into Latgalian include, for example, Lower-German krūgs ‘inn’, šmuks ‘handsome’ or lusteigs ‘cheerful’ (Nau 2012: 475

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2012. “Modality in an areal context: the case of a Latgalian dialect”, w: B. Wiemer i in. (red.) Grammatical replication and borrowability in language contact. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 465–508.

) as well as words like butele ‘bottle’, dzeraune ‘village’ or glups ‘stupid’. The second group is often attributed to Polish, nonetheless little do we know about dialects of Polish once used in Latgale (Čekmonas 2001: 130

) as well as words like butele ‘bottle’, dzeraune ‘village’ or glups ‘stupid’. The second group is often attributed to Polish, nonetheless little do we know about dialects of Polish once used in Latgale (Čekmonas 2001: 130 Čekmonas 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Čekmonas 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Čekmonas, Valeriy 2001. „Russian varieties in the southeastern Baltic area: Rural dialects”, w: Ö. Dahl & M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (red.). Circum-Baltic Languages. vol.1. Past and Present. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 101–136.

), and aforementioned words can as be of Eastern-Slavic origin as well. Latgalian borrowed several words connected with liturgy from Polish (rožanc, spovede, breviars, nešpors, plebaneja, devotka). Other Slavic languages – Belarussian and Russian also had an influence on Latgalian, although mainly in the sphere of phonetics (Balode & Holvoet 2001: 9

), and aforementioned words can as be of Eastern-Slavic origin as well. Latgalian borrowed several words connected with liturgy from Polish (rožanc, spovede, breviars, nešpors, plebaneja, devotka). Other Slavic languages – Belarussian and Russian also had an influence on Latgalian, although mainly in the sphere of phonetics (Balode & Holvoet 2001: 9 Balode & Holvoet 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Balode & Holvoet 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Balode, Laimute & Axel Holvoet 2001. „The Latvian language and its dialects”, w: Ö. Dahl & M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (red.) Circum-Baltic Languages. vol.1. Past and Present. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 3–40.

). It was due to the presence of the Slavic adstrat in Latgalian that the vowel change of æ > a occured. Where Lithuanian has æ, Latgalian has a – e.g. Lithuanian vecs [væts] vs Latvian vacs ‘old’. The influence of Slavic languages resulted in devoicing final stops – it is a phenomenon typical of Lithuanian and Upper-Latvian dialects, but not of other Latvian dialects. (Balode & Holvoet 2001: 20

). It was due to the presence of the Slavic adstrat in Latgalian that the vowel change of æ > a occured. Where Lithuanian has æ, Latgalian has a – e.g. Lithuanian vecs [væts] vs Latvian vacs ‘old’. The influence of Slavic languages resulted in devoicing final stops – it is a phenomenon typical of Lithuanian and Upper-Latvian dialects, but not of other Latvian dialects. (Balode & Holvoet 2001: 20 Balode & Holvoet 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Balode & Holvoet 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Balode, Laimute & Axel Holvoet 2001. „The Latvian language and its dialects”, w: Ö. Dahl & M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (red.) Circum-Baltic Languages. vol.1. Past and Present. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 3–40.

).

).More than 50% of trade terms in South-Latgalian dialects come from Slavic languages (Čekmonas 2001: 131

Čekmonas 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Čekmonas 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Čekmonas, Valeriy 2001. „Russian varieties in the southeastern Baltic area: Rural dialects”, w: Ö. Dahl & M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (red.). Circum-Baltic Languages. vol.1. Past and Present. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 101–136.

). There are functioning pairs of synonyms in Latgalian, in which one word is of Baltic origin and the second of Slavic origin, e.g. barkan - morkovka ‘carrot’ (Latvian - Russian), or both words are of Slavic origin, e.g. pogreb - sklep ‘cellar’ (Russian - Belarussian).

). There are functioning pairs of synonyms in Latgalian, in which one word is of Baltic origin and the second of Slavic origin, e.g. barkan - morkovka ‘carrot’ (Latvian - Russian), or both words are of Slavic origin, e.g. pogreb - sklep ‘cellar’ (Russian - Belarussian).Mutual interactions with other languages are best seen in Latgalian at the end of 19th century, i.e. times from before standardization (Nau 2012: 472

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2012. “Modality in an areal context: the case of a Latgalian dialect”, w: B. Wiemer i in. (red.) Grammatical replication and borrowability in language contact. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 465–508.

), when a great deal of Latgalian texts had already existed. Texts from the 18th and 19th centuries show a strong influence of Polish, on both syntax and vocabulary. Authors of the first texts written in Latgalian were not native speakers of the language (Nau 2011: 5

), when a great deal of Latgalian texts had already existed. Texts from the 18th and 19th centuries show a strong influence of Polish, on both syntax and vocabulary. Authors of the first texts written in Latgalian were not native speakers of the language (Nau 2011: 5 Nau 2011 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2011 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2011. A short grammar of Latgalian. München: Lincom Europa.

).

).The region where Latgalian is used has always been an area of multilinguistic interactions. Instead of claiming an influence of one language on another, one should speak of a mutual parallel influence which resulted in features not usually present in standard Belarussian or Latvian. Such a situation occurs in the case of words expressing modality – for instance, aforementioned mošeņ (see: Genetical classification). In languages used in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – Belarussian, Lithuanian, Latgalian, Polish and Ukrainian – there are two epistemic particles (expressing judgements and beliefs), which are derived from the verbs meaning ‘to be able to’ (e.g. Polish może) and ‘to have to’ (Latgalian mošeņ, Lithuanian dialectal musė, Polish dialectal musi). Although those languages influenced each other mutually, and not just one-sidedly, this phenomenon is a result of the Polish influence which, in turn, borrowed the word meaning ‘to have to’ from Middle-High-German. (Nau 2012:491

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r /

Nau 2012 / komentarz/comment/r / Nau, Nicole 2012. “Modality in an areal context: the case of a Latgalian dialect”, w: B. Wiemer i in. (red.) Grammatical replication and borrowability in language contact. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 465–508.

).

).Latgalian influence on other languages

Russian dialects used in Latgale, mainly by Old Believers, possess few loan-words from Latgalian. Many of their loan-words are from Lithuanian, but above all from Polish, which used to be the language of higher culture in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and was regarded as highly prestigious in times when first native speakers of Russian started settling in Latgale. The Polish language was kind of a go-between of Baltic influence and Russian dialects in Latgale which, on the other hand, was too high. (Čekmonas 2001: 130 Čekmonas 2001 / komentarz/comment/r /

Čekmonas 2001 / komentarz/comment/r / Čekmonas, Valeriy 2001. „Russian varieties in the southeastern Baltic area: Rural dialects”, w: Ö. Dahl & M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm (red.). Circum-Baltic Languages. vol.1. Past and Present. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 101–136.

)

)ISO Code

ISO 639-3 / SIL ltg

- General remarks

- Biogram Maruty Latkowskiej

- Fraszki 1 (474)

- Fraszki 2. (475)

- Glupa sīva; Fraszki 3 (475)

- Fraszki 4 (476)

- Fraszki 5 (476)

- Muote i meita; Fraszki 6 (476-477)

- Brauc cylvāks ar linim; Fraszki 7 (477)

- Fraszki 8 (478)

- Sīva vuorej putru; Fraszki 9 (478-479)

- Sīva, kur namuok aust; Fraszki 10 (479)

- Baznīckungs i saiminīki; Fraszki 11 (479-480)

- Dīvs i valns; Fraszki 12 (480-481)

- Fraszki 13 (481 – 482)

- Fraszki 14 (482 – 483)

- Zaglis pī baznīckunga; Fraszki 15 (483 – 485)

- Tuksneits; Fraszki 16 (485)

- Fraszki 17 485 – 486 (Ap divi italiś).

- Fraszki 18 486 – 487 (Ap divi bruolim).

- Fraszki 19 (487 – 489)

- Mužiceņš i starostys; Fraszki 20 (489)

- Fraszki 21 (490)

- Popa kolps; Fraszki 22 (490 – 492)

- Kdz. 1. (107)

- Kdz. 2. (107-108)

- Kdz. 3. (108-109)

- Kdz. 4. (109-110)

- Kdz.5. (110)

- Teišam jīveņu sylā stotom; Kdz.6. (110-111)

- Gaismeņa ausa (Oi, agri, agri); Kdz.7. (111-112)

- Kdz.8. (113)

- Kdz.9. (113-114)

- Kdz.10. (114)

- Kdz.11. (114-115)

- Kdz.12. (115-116)

- Kdz.13.(116)

- Kdz.14. (116-117)

- Kdz.15. (117)

- Kdz.16. (118)

- Kdz.17. (118)

- Kdz.18. (119)

- Kdz.19. (119-120)

- Kdz.20. (120)

- Kdz.21. (120-121)

- Kdz.22.(121)

- Kdz.23. (121-122)

- Kdz.24. (123-125)

- Kdz.25.(124-125)

- Moza, moza uobeļnīca (Kdz. 26.(125))

- Kdz. 27. (126-127)

- Kdz.28. (127)

- Kdz.29.(127-128)

- Kdz.30.(128-129)

- Kdz.31. (129)

- Kdz.32. (129-130)

- Kdz.33.(130)

- Kdz. 34. (130)

- Kdz.35.(130)

- Kdz.36.(131)

- Kdz.37.(131)

- Kdz.38.(131)

- Kdz.39.(131)

- Kdz.40.(132)

- Kdz.41.(132)

- Kdz.42.(132)

- Kdz.43.(133)

- Kdz.44.(133-134)

- Dzīd ar vīnu (Kkr.1.(135))

- Kkr.3.(135)

- Kkr.4.(135)

- Kkr.5.(135)

- Kkr.6.(135)

- Kkr.7.(135)

- Kkr.8.(135)

- Kkr.9.(135)

- Kkr.10.(136)

- Kkr.11.(136)

- Na eļkšņom taidy goldy (Kkr. 2 (135))

- Es byutumu šūrudin (Roz 13. (180))

- Buoleņš guoja karakaltu (Kar 2. (162-163))

- Sādādama sev duorzeņā (Roz 3. (175 – 176))

- Zīmeļs i Saule (Północny Wiatr i Słońce)

- Kkr.12.(136)

- Kkr.13.(136)

- Kkr.14.(136)

- Kkr.15.(136)

- Kkr.16.(136)

- Kkr.17.(136)

- Kkr.18.(137)

- Kkr.19.(137)

- Kkr.20.(137)

- Kkr.21.(137)

- Kkr.22.(137)

- Kkr.23.(137)

- Kkr.24.(137)

- Kkr.25.(137)

- Kkr.26.(137-138)

- Kkr.27.(138)

- Kkr.28.(138)

- Kkr.29.(138)

- Kkr.30.(138)

- Kkr.31.(138)

- Kkr.32.(138)

- Kkr.33.(138)

- Kkr.34.(139)

- Kkr.35.(139)

- Kkr.36.(139)

- Kkr.37.(139)

- Kkr.38.(139)

- Kkr.39.(139)

- Kkr.40.(139)

- Kkr.41.(139)

- Kkr.42.(140)

- Kkr.43.(140)

- Kkr.44.(140)

- Kkr.45.(140)

- Kkr.46.(140)

- Kkr.47.(140)

- Kkr.48.(140)

- Kkr.49.(140)

- Kkr.50.(140)

- Kkr.51.(140-141)

- Kkr.52.(141)

- Kkr.53.(141)

- Kkr.54.(141)

- Kkr.55.(141)

- Kkr.56.(141)

- Kkr.57.(141)

- Kkr.58.(141)

- Kkr.59.(141)

- Kkr.60.(142)

- Kkr.61.(142)

- Kkr.62.(142)

- Kkr.63.(142)

- Kkr.64.(142)

- Kkr.65.(142)

- Kkr.66.(142)

- Kkr.67.(142)

- Kkr.68.(142)

- Kkr.69.(143)

- Kkr.70.(143)

- Kkr.71.(143)

- Kkr.72.(143)

- Kkr.73.(143)

- Kkr.74.(143)

- Kkr.75.(143)

- Kkr.76.(143)

- Kkr.77.(144)

- Kkr.78.(144)

- Kkr.79.(144)

- Kkr.80.(144)

- Kkr.81.(144)

- Kkr.82.(144)

- Kkr.83.(144)

- Kkr.84.(144)

- Kkr.85.(144-145)

- Kkr.86.(145)

- Kkr.87.(145)

- Kkr.88.(145)

- Kkr.89.(145)

- Kkr.90.(145)

- Kkr.91.(145)

- Kkr.92.(145)

- Kkr.93.(145)

- Kkr.94.(146)

- Kkr.95.(146)

- Kkr.96.(146)

- Kkr.97.(146)

- Kkr.98.(146)

- Kkr.99.(146)

- Kkr.100.(146)

- Kkr.101.(146)

- Kkr.102.(147)

- Kkr.103.(147)

- Kkr.104.(147)

- Rokr 105. (147)

- Rokr 106. (147)

- Rokr 107. (147)

- Rokr 108. (147)

- Rokr 109. (147 – 148)

- Rokr 110. (148)

- Rokr 111. (148)

- Rokr 112. (148)

- Rokr 113. (148)

- Rokr 114. (148)

- Rokr 115. (148)

- Rokr 116. (148)

- Rokr 117. (148)

- Rokr 118. (149)

- Rokr 119. (149)

- Rokr 120. (149)

- Rokr 121. (149)

- Rokr 122. (149)

- Rokr 123. (149)

- Rokr 124. (149)

- Rokr 125. (149)

- Rokr 126. (150)

- Rokr 127. (150)

- Rokr 128. (150)

- Rokr 129. (150)

- Rokr 130. (150)

- Rokr 131. (150)

- Rokr 132. (150)

- Rokr 133. (150)

- Rokr 134. (151)

- Rokr 135. (151)

- Rokr 136. (151)

- Rokr 137. (151)

- Rokr 138. (151)

- Rokr 139. (152)

- Rokr 140. (152)

- Koly 181. (157)

- Koly 182. (157)

- Koly 183. (157)

- Koly 184. (157)

- Gon 185. (158)

- Gon 186. (158)

- Gon 187. (158)

- Gon 188. (158)

- Gon 189. (158)

- Gon 190. (158)

- Gon 191. (158)

- Gon 192. (158)

- Gon 193. (159)

- Gon 194. (159)

- Bor 1. (159)

- Bor 2. (159)

- Bor 3. (159-160)

- Bor 4. (160)

- Bor 5. (160)

- Bor 6. (160)

- Bor 7. (160)

- Bor 8. (160)

- Bor 9. (160-161)

- Bor 10. (161)

- Bor 11. (161)

- Bor 12. (161)

- Kar 1. (161-162)

- Kar 3. (163-164)

- Kar 4. (164)

- Kar 5. (164-165)

- Kar 6. (165)

- Kar 7. (165-166)

- Hum 1. (166-167) O wróblu

- Hum 2. (167-168) O koziołku

- Hum 3. (168)

- Hum 4. (168-169) Dzīsme dzāruoju

- Hum 5. (170 – 171)

- Hum 6. (170)

- Hum 7. (171)

- Hum 8. (171)

- Hum 9. (171)

- Hum 10. (172 – 173)

- Hum 11. (173)

- Roz 1. (173 – 174) Vuškeņa

- Roz 2. (174 – 175)

- Roz 4. (176)

- Roz 5. (176 – 177)

- Roz 6. (177)

- Roz 7. (177 – 178)

- Roz 8. (178)

- Roz 9. (178 – 179)

- Roz 10. (179)

- Roz 11. (179)

- Roz 12. (179 – 180)

- Roz 14. (180)

- Roz 15. (181)

- Diw 16. (181 – 182)

- Diw 17. (182)

- Przysłowia 1 A-C

- Przysłowia 1 D-J

- Przysłowia 1 K

- Przysłowia 1 L-M

- Przysłowia 1 N-O

- Przysłowia 1 P-S

- Przysłowia 1 T-Z

- Przysłowia 2 A-D

- Przysłowia 2 E-I

- Przysłowia 2 K

- Przysłowia 2 L-M

- Przysłowia 2 N-P

- Przysłowia 2 R-S

- Przysłowia 2 T-Z

- Przysłowia 3

- Zagadki A-D

- Zagadki G-K

- Zagadki L-M

- Zagadki N-S

- Zagadki T-Z

- Zagadki 2

- Zagadki 3

- Ap natekle; Baśnie 1 (236-238)

- Ap kazeņom; Baśnie 2 (239-242)

- Ap visteņu; Baśnie 3 (242-245)

- Ap gaileiti; Baśnie 4 (245-248)

- Kai zvieri pi spovids guoja; Baśnie 5 (249-251)

- Kai Dīvs juoja kikerēs iz cylvāka; Baśnie 6 (252-254)

- Ap kungu, kurs acavedēs; Baśnie 7 (254-255)

- Ap kalvi; Baśnie 8 (256-257)

- Ap żydim; Baśnie 9 (257-259)

- Ap valnu; Baśnie 10 (259-261)

- Ap valnu II; Baśnie 11 (261-262)

- Ap valnu III; Baśnie 12 (263)

- Ap zagli; Baśnie 13 (263-264)

- Ap duraku I; Baśnie 14 (264-265)

- Ap duraku II; Baśnie 15 (266-268)

- Ap valna kolpu; Baśnie 16 (269-272)

- Ap gluplu buobu; Baśnie 17 (272-276)

- Ap kaļva sīvu; Baśnie 18 (276-278)

- Ap łopsu; Baśnie 19 (278-280)

- Ap začeiti; Baśnie 20 (281-282)

- Ap trejim vuoceišim; Baśnie 21 (282-289)

- Ap duraku III; Baśnie 22 (290-293)

- Ap eksteiti; Baśnie 23 (294-298)

- Ap div bruoli gudri, trešš [trešs] duraks; Baśnie 24 (298-302)

- Ap buorineite; Baśnie 25 (302-306)

- Ap buorineiti II; Baśnie 26 (306-310)

- Ap buorineiti III; Baśnie 27 (311-313)

- Ap buorineiti IV; Baśnie 28 (313-315)

- Ap treis buorineišim; Baśnie 29 (315-321)

- Ap treis muosys; Baśnie 30 (321-327)

- Ap treis bruoli; Baśnie 31 (327-331)

- Ap murzu; Baśnie 32 (331-335)

- Ap div muosys, trešs bruoļs; Baśnie 33 (335-339)

- Ap kupča dālu; Baśnie 34 (339-344)

- Ap razboinīku; Baśnie 35 (344-346)

- Ap kungu; Baśnie 36 (347-349)

- Ap briugonu nabašnīku; Baśnie 37 (349-351)

- Ap viežu kieniņu; Baśnie 38 (351-360)

- Ap dālu; Baśnie 39 (360-366)

- Ap div dāli; Baśnie 40 (366-369)

- Zeps i peipe

- Montuojums

- Ap taidu, kur bailis meklej; Baśnie 41 (369-375)

- Ap Dīvu; Baśnie 42 (375-479)

- Ap razboinīkim; Baśnie 43 (379-385)

- Ap bednu puisi i ap lopsu; Baśnie 44 (385-393)

- Ap Palnurušku; Baśnie 45 (393-406)

- Indryca- wielojęzyczność Łatgalii z humorem

- przyp01

- przyp02

- Andronow & Lejkuma 2006

- Mercator 2009

- Nau 2012

- Čekmonas 2001

- Balode & Holvoet 2001

- Nau 2011

- Price 2001

- Lewis 2009

- Andronov & Andronova 2009

- Brejdak 2006

- Atlas Języków Bałtyckich 2009

- Cibuļs 2009

- Trasuns 1921

- Strods 1922

- Kossowski 1853

- Skrinda 1908

- Cibuļs & Lejkuma 2003

- Jankowiak 2010

- Šuplinska & Lazdiņa 2009

- Lazdiņa & Marten 2012

- Jankowiak 2009

- Stafecka 2004

- zagrożenie języków / language endangerment

- Deklarowana znajomość języka łatgalskiego 2011

- Flaga Łatgalii

- Języki na Łotwie

- Gazeta internetowa LaKuGa

- Regiony i miasta Łotwy

- Skład narodowościowy Łatgalii

- Stóg w językach bałtyckich

- fotografia przed muzeum w Indrze

- wzory łatgalskie

- stroje łatgalskie i litewskie

- stara Rzeżyca / Rēzekne

- tytuł "Łotyszy Inflant Polskich" S.Ulanowskiej

- "Łotysze Inflant Polskich" S.Ulanowskiej-początek

- W kościele w Wielonach (Viļāni)

- W redakcji czasopisma „Katōļu dzeive”

- Łatgalskie napisy w Rzeżycy (Rēzekne)

- Gaisma – pierwsza gazeta łatgalskojęzyczna.

- Infomacja turystyczna w Rzeżycy (Rēzekne)

- Łatgalski sklep w Korsówce (Kuorsova)

- Łatgalskie napisy w Korsówce (Kuorsova)

- Łatgalskojęzyczny modlitewnik katolicki

- Muzeum literatury łatgalskiej w Rzeżycy (Rēzekne)

- Nazwy wsi w Łatgalii

- „Ojcze nasz” po łatgalsku

- Pomnik J. Macilewicza w Lucynie (Ludza)

- W kościele w Krasławiu (Kruoslova)

- Odezwa w Spisie Powszechnym 2011

- Evangelia toto anno 1753

- Gramatyka Kossowskiego z 1853

- Gramatyka łatgalskiego Skrindy 1908

- Elementarz Kempsa 1905

- Elementarz łatgalskiego L. Paegle z 1925

- Samogłoski języka łatgalskiego

- Latgalian monophtong vowels